At the height of Steve McQueen’s fame in 1968, after a run of huge box-office successes – The Sand Pebbles, The Thomas Crown Affair, Bullitt – it was Robert Mitchum, his elder by 13 years and a star for more than twenty, who was voted the screen’s ‘godfather of cool’ on America’s university campuses.

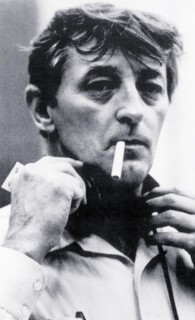

Both men had got to where they were by doing or seeming to do nothing. It was the fashion. Gary Cooper, Clint Eastwood, Lee Marvin, James Coburn, and in England – and in a different, English way – Michael Caine, seldom did anything else. It was also a manner which could not always be easily distinguished from simple idleness. For the first 25 years of Mitchum’s career, his performances were routinely mocked – most consistently by Mitchum himself – for their laziness. James Agee wrote of one of his best roles, the doomed Jeff Bailey in the 1947 film Out of the Past: ‘Mitchum is so sleepily self-confident with the women that when he slopes into clinches you expect him to snore in their faces . . . his curious languor suggests Bing Crosby supersaturated on barbiturates.’ The following year Mitchum would be arrested for possession of marijuana and serve two months in prison.

In Robert Mitchum: Solid, Dad, Crazy, a Mitchum buff’s guide to his most interesting films, and a much better book than its title suggests, Damien Love describes Mitchum’s less-is-more style of acting as ‘a fundamental understanding of what the minute scrutiny of that close camera and the magnification of that big screen could do’. Like many male screen icons of his generation, Mitchum was uneasy with what he did. ‘Acting is a ridiculous and humiliating profession,’ he told interviewers, and called himself a ‘movie actress’. His ‘eternal rationale’, as Love says, for completing 120 films was that it ‘beat working’. His fans insisted that his naturalism – so masculine – and his underplaying refuted any residual sissiness that might be associated with acting; moreover, they claimed, he so entirely inhabited his roles that he was ‘being, not acting’.

Mitchum’s screen persona – seen-it-all, lazy, knowing, amusedly disaffected – gave subtle signals that it was grounded in his own experience. From the mid-1940s, when he first became a star, he quickly acquired a reputation in Hollywood for bad behaviour and wilful independence. He deflected studio attempts to change his name, and got into trouble for his drinking and its consequences: fights with policemen, a habit of dropping his trousers and removing his clothes when provoked and, famously, peeing on David O. Selznick’s carpet (in the middle of a meeting about a film version of A Doll’s House). He was articulate and rude to journalists, which also generated copy. ‘Booze, broads, all true,’ he told hacks. ‘Make up some more if you want to.’ Mitchum was the first star whose bad publicity only made him more popular; after his 1948 drug bust there were queues for his next film, Rachel and the Stranger; excitable young girl fans (known as the ‘Droolettes’) panted over his ‘immoral face’.

Born in 1917, Mitchum lost his father at two and was brought up in comparative poverty by his widowed, bohemian mother. He was clever, rebellious and lazy. He won prizes for poetry but was expelled from school, apparently, for defecating in a teacher’s hat. By the age of 20, when he came to Los Angeles, he claimed to have spent several years as a ‘scenery bum’, hitching on boxcars round depression America; to have spent a week on a chain gang; to have nearly lost a leg; and to have seen the absolute lowest to which humanity could sink. At the same time he was a famous embroiderer of stories: ‘I learned early in life that by telling a story far more colourful than the truth . . . one’s truth is let alone.’ So who knows?

He took to acting not least because he found it easy. He served his apprenticeship as an extra in Hopalong Cassidy westerns, in which the main obligation was to be able to ride a horse, shoot a gun and look comfortable in front of the camera. There was no direction to speak of. William Boyd, who played Hopalong Cassidy, was, as Lee Server notes in his extremely long but enjoyable Robert Mitchum: Baby, I Don’t Care, ‘a scrupulous underplayer’, who made everything he did look natural and never upstaged or demanded close-ups. Mitchum seems to have soaked up from Boyd – and the 21 B-movies he made in under two years – everything he needed to know about how the camera worked and what to do in front of it. He could also memorise dialogue instantly, a fact much remarked on by his directors; he looked imposing, sleepy-eyed, graceful and utterly at ease. He was a natural. He got his break in 1944 with When Strangers Marry, a film noir and eventually a cult; in it he plays a smooth travelling salesman who turns out to be a disturbed murderer. By then, what Server calls ‘the deadpan macho schtick, the cynical hipster outsider stance’ were in place.

Over the next ten years he became a star. He initially worked as a contract player at Howard Hughes’s RKO. (Hughes, a control-freak, had Mitchum’s house bugged: Mitchum, with characteristic contrariness, always insisted he liked Hughes.) His best roles were largely in film noir and dark westerns, the most famous of them Out of the Past and Charles Laughton’s expressionist fantasy Night of the Hunter – in which, as the eye-rolling Preacher, he was most definitely not underplaying. His roles exploited both his beefcake ease, and his ability to suggest emotional ambiguity of a type that mainstream Hollywood did not usually care to explore. Mitchum was always recognisably Mitchum, but his persona – unusually for a Hollywood star – encompassed an extensively nuanced range of qualities, from smiling threat to melancholic apathy, to insolent, good-humoured cynicism, to stoic vulnerability, to hounded weakness. It made him one of the – if not the – most interesting American screen actors of his generation.

Mitchum worked uninterruptedly until his death in 1997. As he got older and his reviews got more reverent, the films tended to get less interesting, though watching him was almost always a pleasure. Among his best late performances are the dignified, wounded schoolteacher, so uncomfortable in his own huge body, in Ryan’s Daughter (a watchable film once you decide that it’s Mitchum’s movie, and take a long tea-break in the middle), and the worried, small-time crook in The Friends of Eddie Coyle. He never stopped mocking himself and his work: ‘120 pictures altogether, forty of them in the same raincoat’; a career in which ‘I changed nothing except my underwear.’ Like many people who find what they do best easy, he was also frustrated – by his own laziness, as much as anything else. He wanted to prove that he was educated, literate and sensitive: before he took to being a ‘movie actress’, he had been an aspiring writer of sketches and lyrics; he’d even written a couple of (unproduced) plays. Charles Laughton’s wife, Elsa Lanchester, partly resentful of her husband’s evident fascination with his movie’s star, claimed that Mitchum was forever using ‘big, long words’ to impress Laughton. Yet at the same time he couldn’t stop himself from playing the vulgarian and disgracing himself. And while he seized on roles that demanded more of him, he became harder and harder to stir into action as he got older, and more and more resentful if anyone tried to direct him – while simultaneously regretting that he seemed to be asked to do the same performance over and over again.

He appears to have had fun, however. If he was often bored by what was required of him, he had a good time doing it: ‘telling stories for days’, travelling the world, embarking on affairs – including a three-year relationship in the early 1960s with Shirley Maclaine, while his long-suffering wife, Dorothy (they were married for 57 years), stayed at home. When Jane Russell, a family friend, and his co-star on two films including Macao – the film which prompted Howard Hughes to write a multi-page memo on the subject of her breasts – was asked to choose her favourite Mitchum film, she said: ‘I just like . . . Robert Mitchum movies.’ It’s a sentiment many film-watchers have shared, and one Mitchum would have loved, while pretending not to.

Steve McQueen’s doubts about acting as a man’s profession were even more profound than Mitchum’s had been, and, not coincidentally, he pushed the impassive style even further. Norman Jewison, who directed him in The Cincinnati Kid, claimed he was ‘the only actor who I’ve ever taken lines away from who loved it’. ‘I’m not sure that acting is something for a grown man to be doing,’ McQueen would say, and he spent a remarkable amount of time in what might now be thought of as over-compensatory masculine pursuits: racing cars and motorcycles, drinking beer, hanging out with Bruce Lee and a great deal of what he liked to call ‘schtupping’. By the mid-1970s McQueen was so bored of movies that he charged $50,000 to read a script and gave up acting altogether for two years.

Reading between the lines – as you have to do in Christopher Sandford’s clumsy, ill-written McQueen: The Biography – it is clear that there was never anything very laid-back about McQueen, an actor of far less range than Mitchum, but far more troubled. What is most striking about him is how hard he schooled himself in the role of laid-back minimalist star. There was nothing undeliberate about it.

He had a miserable childhood. He was born in 1930 – within a few weeks of Clint Eastwood and Sean Connery – in Indianapolis, to an alcoholic, and, according to Sandford, semi-prostitute mother, who abandoned and reclaimed him periodically through his childhood. He spent half his early years truanting on his great-uncle’s farm in rural Missouri, and the rest following his mother round a series of urban slums with a series of unsavoury boyfriends, one of whom, Sandford speculates, might have sexually abused him. Deaf in one ear, a bastard, a Catholic in a Protestant area and semi-literate, McQueen seems to have felt isolated and badly treated by the world from early on. ‘My life was screwed up before I was born,’ he told an interviewer.

By the age of 14, living with his mother and stepfather in California, McQueen was stealing hubcaps and running a street gang; following an appearance in a juvenile court his mother sent him to reform school for two years and never visited him. The school was called Boys Republic. Sandford claims that McQueen escaped five times and was ‘put in solitary’ – a perhaps too convenient echo of his experiences in The Great Escape (the incident is not reported by an earlier and better biographer, Marshall Terrill). In fact Boys Republic was a progressive school which operated on trust rather than punishment and McQueen later credited it with having done a great deal for him. He made large charitable donations to the school until his death.

Following his graduation from Boys Republic, McQueen spent five years as a drifter playing pool, in the Marines, working in the Texas oilfields, selling encyclopedias, working as a prizefighter and as a runner in a brothel. In 1951, in New York, he enrolled in an acting class. He always insisted that it was a girlfriend’s idea: he had been planning to become a tiler. He went along with it because ‘there were more chicks in the acting profession who did it.’ Though his biographers have tended to accept this justification, it’s clear that McQueen wanted to be an actor very much more than he cared to admit. There was an obvious connection between his childhood and his choice of a profession which caused him always to court rejection and demand praise and affirmation. It took him four years to win a place at Lee Strasberg’s Actor’s Studio. (I was surprised that he’d trained there, as he seems the least ‘methody’ of actors. He later credited Strasberg with ‘unlocking’ his talent.) It was not until 1958 that he finally got his big break: a hit TV western series called Wanted: Dead or Alive, in which he played a bounty hunter.

McQueen was fiercely ambitious, deeply competitive with other actors, and once he had some power as a star, determined, to the point of tantrum and beyond, to get what he wanted – which most often was what he called ‘face time’. On the set of the 1960 The Magnificent Seven, which made him a star, he was known as ‘Supie’, short for superstar, and ‘Tricky Dickie’ because of the lengths he would go to to steal scenes. One story goes that every time Yul Brynner – who as the nominal star was always in the centre of the shot – opened his mouth, McQueen, in the background, would fiddle ostentatiously with his hat. Another claims that Brynner built himself a little mound of dirt to stand on to make himself look taller, and that McQueen would quietly kick it away during the course of a take, so Brynner got progressively shorter. McQueen liked to say that he had no time for the Hollywood ‘suits’, but, according to Sandford, until age and illness mellowed him a little, he was often hated by both cast and crew. He was never shy about getting people sacked and on his penultimate film, Tom Horn, he got through five directors – including, briefly, himself.

McQueen steals The Magnificent Seven not through hat-waving and underplaying, but because he laid siege to John Sturges to persuade him to increase the size of his role, and was charming and animated on-screen while everyone else was busy being dour. Charles Bronson and James Coburn were underplaying each other into inanimacy; Brynner was playing Gary Cooper. McQueen was the light relief: insouciant, flashing his beautiful smile, and far more appealing than the notional juvenile lead, the mildly embarrassing Horst Bucholz. He was certainly not a minimalist. It’s claimed that when he signed on to do the film he had only seven lines of dialogue; in fact he had more than that in the first scene alone. At one point someone even says to him: ‘Do you ever get tired of hearing yourself talk?’ Two subsequent forgettable films, The Honeymoon Machine, a weak comedy about an attempt to break the Venice Casino, and the 1963 Soldier in the Rain, in which he was cast as a supposedly lovable idiot, show that McQueen could be a very fussy, mannered actor.

The McQueen persona was refined with help from his first agent, Stan Kamen, and his first wife, Neile, who brought him scripts, encouraged him to restrain his performances and steered him away from comedy and towards those roles which made use of his preoccupation with toughness and masculinity, his edge of nastiness and his impassivity. The cool was willed and created. The look was too: McQueen told journalists that he ‘didn’t give a shit’ about clothes, but he was extremely aware of his appearance – Sandford describes him riding around bare-chested on a Harley in his New York days – and employed a stylist, Jay Sebring, who helped him to create his look, choosing his jeans, his roll-neck sweaters, his sunglasses and his car-coats.

McQueen’s beautiful, monosyllabic, slightly smug inscrutability is exemplified in his two major roles of 1968, the millionaire thief Thomas Crown and the almost silent cop Frank Bullitt. Behind the movies, the success and the undiminished popularity of his image, however, is a sad story. McQueen didn’t enjoy his success much. He was ill-humouredly envious of other actors – Paul Newman, an early rival, was christened ‘Fuckwit’ – and, in the 1960s at least, combative with almost everyone who worked on a film with him. When Richard Attenborough asked James Coburn why McQueen was so rude to him and all the other British actors on The Great Escape, Coburn replied: ‘Paranoia.’ While plenty of other actors, Mitchum included, were cheated by Hollywood, McQueen did well out of it, but was neurotically pennypinching and mean: on one occasion he struggled for 24 hours over a four-page letter itemising a couple of teapots, two sweaters and a pair of boots that he claimed he had been wrongly charged for on set: after a year of arguing $7.50 was docked from his pay cheque. McQueen ‘complained about it, often bitterly, for the rest of his life’.

His unfaithfulness was of Kennedy-like proportions. In the 1960s, Sandford claims, he slept with 200-300 women a year. Despite his ‘astral sex drive’, his biographer asserts, generously, that McQueen wasn’t ‘likely to thrill the girl. Steve was very much a wham, bam guy.’ Sandford also quotes his daughter: ‘My dad hated all women but me.’ He was probably – Sandford mentions this but never explores it – a manic depressive. He was certainly possessed of a deep sense of inadequacy. Things started to go downhill in the early 1970s. His pet project, the incredibly tedious racing movie Le Mans, was a flop, he was taking too many drugs and the collapse of his 15-year marriage (he discovered that his wife had had one affair – with the actor Maximilian Schell – and was so overwhelmed by the betrayal he beat her up) brought him close to breakdown. In 1972 he met the Wasp actress Ali MacGraw on the set of Sam Peckinpah’s The Getaway. McQueen thought MacGraw was ‘heavy, well-educated, classy’ and had ‘the greatest ass of all time’. They married, and for 18 months he was apparently faithful, but also increasingly reclusive and insistent that MacGraw give up her film career and friends to be a housewife. He, meanwhile, spent much of the mid-1970s in front of the TV with a beer and a gun, eating junk food, and going to flea markets to buy hubcaps and 1930s memorabilia (on his death he owned 10,000 penknives and 101 rocking-chairs). The marriage fell apart in 1977. McQueen’s return to the screen in 1978, in a production of Ibsen’s Enemy of the People, produced in a fit of self-improvement and reinvention (and perhaps as a rebuttal to MacGraw for what he saw as her rejection), was widely panned. I like his later films, but I haven’t seen that one and don’t know anyone who has. ‘As he grew older, sadder and sicker,’ David Thomson said of him, ‘something like grace arose in his battered, tense face.’ He swapped the smug confidence of the mid-1960s films for a series of characters who are visibly bewildered by a world that has left them behind: the timeworn lost rodeo cowboy in Junior Bonner, a part McQueen described as ‘a dinosaur, just like me’; the half-mad obsessive prison escapee in Papillon, even the perplexed ex-con in the ineffably nasty The Getaway.

I particularly like Tom Horn, McQueen’s penultimate film, during which he was clearly ill, but did nothing about it: he died a year later of cancer, aged 50, in 1980. It tells the story of an ageing Indian fighter, Horn, a historical figure best known for tracking down the renegade Apache Geronimo and arranging his surrender to the US Government. Horn is hired at the turn of the 20th century as a stock detective, but is framed for murder when his employers decide that his brutal methods are bad for business. The old cowboy, as in so many westerns, incarnates both the brutality and innocence of the Old West, displaced by the civilising, corrupting influence of towns and farming. When the film came out in 1980, westerns were even more unfashionable than they are now and it was dismissed. It has a cold, grey, crisp look, in keeping with its status as a revisionist western stripping down the myth of the hired gang. Horn virtually allows himself to be hanged: why is never explained. McQueen plays him as a barely civilised innocent, who is at the same time defeated, tired and all too aware that there is no room for men like him any more. At his trial, in his prison cell, even at the gallows, he is like a caged creature, his eyes so drawn to the hills that he is hardly able to give his attention to anything else. He looks worn, the fineness of his once perfect features blurred, and gives a quiet, brave performance, one that is, at last, almost as nuanced and complex as those that Mitchum effortlessly produced.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.