This is the first part of a two-part interview. Part 2: ‘The Price’.

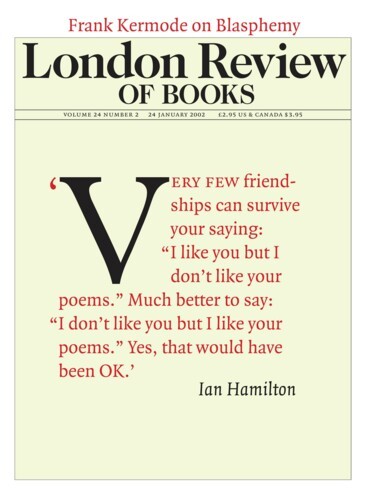

Ian Hamilton died of cancer on 27 December 2001, aged 63. It was a death that the ‘LRB’ has especial cause to lament. He was a great support to this paper, helping to get it going in 1979, serving ever since on its editorial board, and above all contributing many exact, unsparing and funny pieces on poetry, on novels – and on football. He will be missed more than we can say.

Where shall we begin? How far back do you want to go?

Why don’t we go back to the Battle of Bannockburn?

No, not that far. Your schooling. Your birthplace.

King’s Lynn. I was born in Norfolk.

Were both your parents Scottish?

Yes.

And your father was an engineer?

Yes. A civil engineer, built sewers, I think.

– Which is a very Scottish thing to be doing.

Building sewers?

No, being an engineer.

In King’s Lynn where he had his job? This was 1938. He’d been working and living in Scotland, got married, then got a job. He was on short-term contracts when the war came. He moved to King’s Lynn and had some job to do with airfield runways – which there were a lot of in East Anglia. He was also in the Royal Observer Corps. Well, he’d have been then about forty. He was born in 1900. I think I was about twelve when we moved to the North. After the war he was on short contracts all around the place and was rarely at home. Then – in 1951 – came this opportunity to get a longer contract in Darlington, County Durham. So he moved the whole family up there and proceeded to die less than a year later. So there we were in Darlington, not quite knowing why.

Were all of you there?

All of us. Three boys and a girl. She had just been born. I attended the local school in Darlington, learning to ‘speak’ sub-Geordie and how to get used to these rough Northern boys who masturbated all the time.

Yet you were from a family of high achievers.

Well, we had sort of genteel middle-class pretensions.

But your oldest brother –

Oh, you mean the children went to university and all that, yes.

Your father had been a professional person.

He was a bit disappointed and thwarted professionally. He’d had to leave university after a year or so, and hadn’t completed his degree and thereafter was always trying get something which we never stopped hearing of called the AMICE, which was the qualification for civil engineering –

Associate Member of the Institute of Civil Engineers?

Yes. So he was always theoretically studying for this thing which he was clearly never going to get but which, had he got it, would have put him in line for better jobs than the ones that were actually available to him. He was always in a sort of bad temper about not being able to get jobs he thought he was equipped for. A certain amount of this one overheard as a child and afterwards my mother used to go on about it. My father saw himself as a bit of a failure professionally – through no fault of his own.

How old were you when he died?

Thirteen.

You later wrote several poems about it. There’s one called ‘Father Dying’ in ‘The Visit’, your first collection. Is that the one where he speaks of wearing ‘Ibrox blue’ the next time you’ll see him?

No, that’s a different poem – ‘Colours’. Same theme, though. During his last months I used to – not nurse him exactly – but sit around with him. I hadn’t seen him, well, I’d barely seen him during my childhood, so I felt privileged to have this kind of access. I used to spend a lot of time with him.

You’d barely seen him because he’d been away so much?

Yes, he’d always been away, whereas now, here we were, all together. It was known that he was going to die. Mother knew. And I think my older brother knew. So they were comforting each other. The house was chaos, with decorators and builders. My father was in his room and I would drift in there. I was of an age when I wasn’t much use for anything else. So I used to sit there as an errand boy and got very involved in his predicament. There were lots of sick death-jokes, grins, all that. I didn’t know how ill he was, though I’d overheard snatches of people’s talk and picked up the general atmosphere, but nobody ever told me that he was going to die. Then, eventually, he was carted off to hospital, which is, I think, what that Celtic-Rangers poem was about, the final joke he made. He said he’d turn blue – the Glasgow Rangers team colour – by the morning. Which he did; he didn’t last the night. That was upsetting for a 13-year-old lad, and then it became much more upsetting in my twenties when I began to think more about him and what kind of life he had had, what kind of person he was. You lose the pattern, losing a parent when you’re young. I also felt the wish to speak to him or in some way to have a relationship with him. And those poems probably come from an impulse of that sort, from the delayed pain or loss.

Were you close to your siblings, not necessarily as a consequence of this, but . . ?

When you’re a child a gap of three years, which there was between me and my older brother, is a long one. He was three classes ahead of me at school. My younger brother was five years younger. But we were, yes, pretty close and became closer as these age differences didn’t seem to loom so large. We had the sense that we had to look after our mother. No relatives were nearby. They were all in Scotland.

Presumably your mother had to go to work, with such young children to provide for.

She took in lodgers. Indeed, that’s how she managed. But my father had had this Scottish thing about education, so there was no question of any of us leaving school or getting a job.

Money was always very tight then?

We had a rather wonderful well-off aunt in Glasgow, my father’s youngest sister, who owned several fish-shops, and every week she would send us a parcel of fish by British Rail. It was one of the boys’ jobs to go and fetch this parcel every Monday – and in summer it sometimes had to be carried at arm’s length. One of the reasons I never learned to swim, I suppose. But no one ever said the fish was off, neither us nor the half-poisoned lodgers, and that parcel formed the week’s menu: finnan haddock, chicken, sole. At Christmas the chicken turned into a turkey. Two days a week we would eat haddock, three days chicken, and so on. This aunt was very generous and helped in other ways. She’s since sold the shops; she’s very old now.

Do you keep in touch?

Vaguely. I looked her up about ten years ago, the anniversary of my father’s death, I think; and she was still lively and pert. And she showed me lots of old family photographs and things.

Was there much reading going on in the house?

By the time I was 16 I’d read every book in the house. There were popular boys’ books of an earlier time, for some reason: Henty, Ballantyne, that sort of thing. There were lots of self-educating books, home encyclopedias, home university courses, Pelmanism manuals, self-improvement tracts – volumes that were all in the grand, glass-fronted bookcase. Therein lay knowledge. Therein lay my father’s studies . . .

Newspapers?

Oh, the Daily Mail would be considered middle-class and therefore rather smart. No, not smart, but respectable. Respectability was the aim.

Can you remember any of the lodgers?

I can remember them fairly distinctly. My mother hated them.

Did you feel neglected because of them?

No, because she treated them so badly. They were always sort of sealed off from the family and I couldn’t imagine why they wanted to stay.

Like Mr Bleaney in the Larkin poem.

Very Mr Bleaney except that they tended to be young. There were one or two junior Army officers who lodged with us. They must have been attached to Catterick, the nearby Army barracks. There were some odd seedy Bleaneyish types who took a fancy to my mother in a disgusting sort of way. One of them actually proposed to her.

You knew this at the time?

He had a moustache, so we feared the worst.

Rakish, was he?

Yes, postwar-rakish, one of those dubious postwar ‘spiv’ figures. I think he was some kind of salesman, looked at himself in the mirror all the time. It was no surprise when it turned out in the end that he was a ladies’ man.

I was most impressed when you recited to me, off by heart, the whole of ‘Mr Bleaney’ after you’d moved into your previous flat.

Oh, I have a strong sense of identification with it. It’s a wonderful poem.

You went to the local grammar school, which was rather a good one, wasn’t it? What’s become of it now?

It’s a sixth-form college, I think. Or perhaps a university.

When did you discover that books were going to be one of your big things?

I think it had something to do with the fact that when I was about fifteen I had some kind of heart problem and therefore wasn’t allowed to do games, which I was very keen on.

All games?

Well, soccer particularly.

Cricket?

Not so much. I liked cricket but I was never any good at it. I wasn’t allowed to play games because of this so-called heart problem. It was something I got after I’d had scarlet fever, a sort of follow-up to that. My heart was beating too fast, it wasn’t doing its job, and as a result I was classified as a sickly figure and sat in the library during games.

The town or the school library?

The school library.

And the other boys were very young and healthy? And you could hear their shouts from outside? This is getting to be very poignant.

Yes, so I reached for my Keats. I developed a kinship with sickly romantic poets who couldn’t play games. Keats, I suppose, was pre-eminent. You know, ‘half in love with easeful death’ –

So it was through poetry that you became bookish. Not fiction?

No, not at all.

Keats became quite big for me too, but first I had to go through miles of prose – everything – Biggles etc.

Those sorts of thing did figure later, or maybe they were around, but they weren’t as central to my predicament as Keats was. I became a Keats figure, sitting in the library in consequence of not being allowed to do what I really wanted to do, which was to play football. As a result I assumed some of the affectations that went with that. Which included writing for the school magazine on poetic subjects.

Writing on poetic subjects or writing poetry? You must have been good at English. You must have been a star at essays.

Well, not quite a star. But the masters thought I was pretty good and so I came to see myself in this role. You know – take a look at my sensibility which is surely superior to yours. By all means clatter off to your games, you muddy fools. In truth, of course, I envied them because that was the real poetry, so far as I was concerned.

Still is, perhaps.

Yes, still is.

At your school did you write general essays, as part of the English course? We used to do it all the time. We didn’t write ‘criticism’ until quite late. We would write on ‘topics’.

That came under ‘general studies’. They were the thing at the time: capital punishment, pro and con. We had to do a fair amount of that.

You weren’t encouraged, as we were, to go in for little whimsical Charles Lamb-like essays? Writing trivia about trivia?

No. The senior English master was a raging Leavisite, an absolute caricature.

Had he been to Cambridge?

No, he’d been to Southampton and had been thoroughly instructed there by a sub-Leavisite. At that time, Leavis’s word was spreading through the country. This teacher of mine was a great zealot. I didn’t know this, of course. I just thought he was a man of very definite opinions and rather narrow tastes. Nonetheless he was very good at teaching one how to write. He may have been wrong in some of his literary judgments and ignorant in some areas of literature but he was good at getting rid of what was superfluous or phoney in a piece of writing. And he would be very insulting if one came out with some bit of frippery. Anything redundant, artificial, not to the point, tautologous, repetitious. You got the essays back covered in brutal red inscriptions. So, impressing this teacher became most important to me.

He was trying to make you feel small but he ended up making you feel big.

Absolutely. When I got fewer red marks than these other guys, the footballers, I began to think I was getting somewhere. This teacher – call him ‘P.J.’ – rarely praised anybody. Or if he did, he praised them at someone else’s expense. So there was a very unpleasant atmosphere in his classes. Everybody was afraid of him but it was very effective. I’ve since talked to others – a chap for instance who was at the school and who now writes books. This character was terrified of P.J. and hated him but he now acknowledges that if it had not been for suffering this teacher’s lash he might not today be writing as well as he does. And he does write really well. P.J. turned us all into little intellectual snobs. But we knew how to write – or rather we knew how to recognise bad writing.

Were you in small groups?

No, large classes, but as you went on into the sixth form the classes got smaller and smaller. By the end there were maybe half a dozen haggard figures sitting in a room, being tongue-lashed by this pedagogic monster.

How did you move on, in terms of your reading, from Keats? Presumably you had set texts.

Oh, yes, one was doing all that. But there was also his personal syllabus. He was, of course, scornful of the official syllabus, because it had people like Dickens on it, and he didn’t approve of that.

‘Entertainer’ was the word Leavis used about him.

Laughter and tears. But one read also in anthologies. In this way I got on to various people who, like Browning, P.J. hadn’t had any time for but I quite liked. I didn’t dare mention Browning in class in case this man might explode. So one did a lot of ‘sneaky’ reading. Also I started writing for the school magazine.

In the sixth form you started your own magazine – or even earlier?

No, in the sixth form.

You’d found a cadre of contributors?

Yes. You know: chaps in polo-necked sweaters, sixth-formers in horn-rimmed glasses . . .

With heart conditions.

Yes, the intellectuals. I had a few of those. They were disaffected in different ways. My journal came out on the same day as the official school magazine.

Was it printed or cyclostyled?

Oh, printed.

Who printed it?

Some local printer. We all saved up our cash. It came out for two issues.

And you timed it deliberately to rival the school magazine?

Yes. I got into a lot of trouble.

I remember your telling me that the magazine was called the ‘Scorpion’, is that right? No doubt because scorpions sting, inject poison into the system? Was its general tone sneering and satirical?

Not particularly. In fact, it was pretty tame stuff. I put a certain amount of bile into the editorials, but they didn’t really connect with the rest – which consisted of the usual morose adolescent parables and things like that. The first issue had a foreword by John Wain, the novelist, who had just appeared then and was very famous. I wrote to him to ask if there was some message he could send to youthful aspirants and he did. It was rather good, about half a page, which ended: ‘and, if all this fails, back to the drawing-board!’ – a phrase I didn’t know then. The second issue again showed this wish to connect with the London literary world. I sent a questionnaire to various luminaries asking if there was advice that they would wish to give to young authors at the beginning of their literary careers.

You were an ambitious bugger even then.

Oh sure, always on the make. We got back forty to fifty replies.

Fifty! Can you remember any names?

There would be some names that would not be recognised now; figures like Louis Golding who was popular in that day. I just picked them out of some magazine or book. So about half of this combative magazine, this Scorpion, was filled with these platitudes from London literary figures.

Were you flattered?

Oh, yes. They felt a social obligation to bring wisdom to the youth . . . Well, that sank the thing.

I can imagine it sinking it from the literary point of view, but I’d have thought the authorities would have been pleased you’d netted such big fish. Yet you say it got you into trouble.

Well, I’d brought it out on the same day as the official school magazine. It was an anti-school magazine. I think I had to go into town and take delivery of it from the printer and this meant skipping x number of lessons. And I’d been selling it around the town, so I wasn’t at school very much. I was disciplined. I think I remember having my prefect’s badge stripped from my lapel. In fact, it was because some master had a stake in the official magazine and thought that this bastard, me, ought to be sorted out.

Have you got any copies of the ‘Scorpion’?

Yes. They’re in my mother’s house.

Do you remember what you wrote for this magazine?

I seem to remember writing some dark allegorical story.

Poems?

No. I’d written odd poems, very sub-Dylan Thomas. I remember having or buying Thomas’s Collected Poems. I liked the whole idea of him so anything I wrote sort of resembled him, though I pretended it didn’t.

Were you working quite hard in the sixth form for your Oxford entrance?

Yes.

And why Oxford, if you had this raging Leavisite for a teacher?

Oh, because my older brother went to Cambridge.

He read – what, natural sciences?

Medicine, yes. I was not expected to get into Oxford, so it was all a bit of impertinence on my part. Darlington Grammar School students usually went to Durham University. There was an arrangement of some sort with the school.

Your brother had beaten a path anyway.

Well, he was older and was well on the way when we moved to the North. He’d already had lots of academic success, so it was all right for him to want to go to Cambridge. And also he was a science student. The new school was rather proud of him and encouraged him to get his place. In my case, they thought I was getting above myself.

And the Leavisite?

Oh, he didn’t like it at all. He thought there was no chance of my getting into Oxford. But because of my brother I was determined to go there. I had no real idea, no reason for this apart from wanting to make people envious and the girls think I was interesting. And Oxford being famous and grand and all that.

How were you doing with the girls?

Lousy. I needed an Oxford. The magazine didn’t work.

Did you have any female contributors? Or was it a boys-only school?

Oh, entirely.

How old were you when you went to Oxford?

Well, you had to do your National Service in those days. They tended to accept you for university two years hence, as it were. It would have been for 1958 I was accepted although I took the exam in 1955.

What branch did you serve in?

The Air Force. The Information Service.

Where did you do your informing?

Germany. A place called München-Gladbach. By the time I got there we and the Germans were buddies and my job was to promote Anglo-German relations.

Had you done German at school?

No, not at all. French and Latin, I’d done. In Germany I had to write the scripts for a radio programme; I had to write local-boy stories, stories which commemorated a proud day in the life of Blank from Blank. Such and such a grand person came to visit etc, and then you took pictures of the dignitary with some airmen and would find out where they lived and fill in all the blanks for their folks back in England – for their local papers.

Did you enjoy your time in National Service?

I hated it at first because I had to do all the arduous basic training. And the trade training later. I was trained as a typist and it was not for some months that I was plucked from a typing pool and went into Information.

Did you travel back and forth to England?

I was in Germany the whole time, except for some short leaves.

Did you make any friends in the Air Force, meet any kindred spirits?

I had one or two mates, but nobody I kept up with. Occasionally I’ve had letters from ex-colleagues who’ve seen something I’ve written.

And I take it you acquired very little German?

Hardly any. I went to one or two classes and I picked up a smattering, enough to order a drink.

Did you do any writing of your own during this time?

Oh yes. I had become a playwright. I’d read Look Back in Anger and thought it was wonderful.

You’d read it, not seen it?

I don’t think I’d ever been to the theatre. But I loved those hate-filled speeches. I wrote two plays, plays since destroyed.

Their titles have to be recorded, if only for the intensity of adolescent self-pity they reveal: ‘Like a Leper’ and, even better, ‘Pity Me Not’.

‘Like a Leper’, I think, had the edge on ‘Pity Me Not’; but there we go. I’m not sure which was which; but one of them I sent to Ronald Duncan at the Royal Court. Immense crowd scenes, people standing around, pitying the hero – i.e. me.

It sounds very like Duncan.

It was. This Way to the Tomb was his big play at the time. I liked that title.

You say you also wrote a more overtly political play.

There may have been another play early on.

A one-acter?

Yes, possibly.

Peter Dale told me you once produced a play at Oxford, a small piece by Harold Pinter.

I had started another magazine at Oxford called Tomorrow. And for its fourth issue I’d written to Pinter. He had just become prominent then, but I’d learned about him earlier, when I was in Germany. Another of my jobs there had been to work on this radio show, and one of the things I did for it was write a report on a local drama festival. There was a play in the festival by a person I’d read about in the Sunday papers. The Room, it was called, and it was by Harold Pinter. It had had a good review from Harold Hobson in the Sunday Times, but rather dismissive reviews by other people. Anyway I was intrigued by this play, and liked it best of all those put on during the festival – and said so in my radio report. But I’d left the proceedings early in order to write the piece; I hadn’t stayed to hear the commanding officer of the Second Tactical Air Force, who was giving the prize to some Somerset Maugham thing, denounce this incomprehensible piece of garbage by someone called H. Pinters, saying how he just couldn’t understand how anybody in their right mind could have put it on. The next day my piece was broadcast on the radio, praising that very play. My immediate superior, who was the information officer, got hauled up by the commanding officer and told to discipline me. What I had done was ‘tantamount to disobeying an order’.

So critical judgment had to give way to Air Force regulations.

Very much so. The entire weight of Nato was behind him. Several years later I wrote to Harold asking for a contribution to the magazine in Oxford and mentioning that incident. He’d heard about it in the way that one would, because at that age, starting out, one hears of everything. Anyway, he was taken by the story and sent me the script of a radio play called A Slight Ache for publication in the magazine. It doubled the size of the issue. In order to promote the magazine I decided that the play could work very well as a stage play too. So I mounted this production.

Where? At Keble?

No, no. In the Mechanics Institute. And Harold came and saw it and that’s how we became friends. Indeed the play went on to become a stage play put on in the West End. But originally it was a radio play.

Pinter didn’t take any part in the production?

Not at all; he just grandly came to inspect it. But he was pleased and all that.

Strange the effect his work had then. Do you remember those West End revues? I was sitting in one such when there came up a five-minute piece about some people in an all-night café, and I can remember lighting a match in the dark to see in the programme who had written it. I was so struck by it.

He started off doing five-minute sketches like that. He’s brilliant at them.

To go back to Germany and your own plays. Did you send them out?

Yes, I did.

While you were in Germany?

On some leave probably. Each of them had this ranting central figure –

Like ‘Look Back in Anger’?

Yes, but with a larger cast. I sent it off to the Royal Court because I’d read lots about it and the play was taken up for a bit by Ronald Duncan, who was on the board of the theatre. What I didn’t realise was that he was the reactionary figure at the Royal Court and was well known for his opposition to John Osborne, my hero.

Duncan was involved in that post-Eliot ‘revival’ of poetic drama.

Yes, he wanted more verse drama. He also thought that drama should be on some major theme which, indeed, mine was. My play was also laid out like verse, though it wasn’t in fact verse. I mean if there was any way of being pretentious, I took that way. But he did write me various encouraging letters so for a time I went around seeing myself as a –

You sent only the one play, then?

Yes, the more mature one. The other I viewed as apprentice material. I think Duncan got fired or resigned. He clearly lost this battle of poetry v. the kitchen sink – of which I knew nothing until later. He was just a name on the notepaper as far as I was concerned. Anyway, that was the end of that. For a moment it did seem that they or he would have done it. Happily, they didn’t.

Were you reading literary magazines? What was on offer? The ‘London Magazine’ had only recently been started.

Just started. I used to read it.

‘Penguin New Writing’?

Things like that. I started collecting them. It was rather fun to collect.

And ‘Horizon’?

I had the odd copy but it didn’t communicate with me. The London Magazine was the one that mattered. There was also a thing that’s now defunct called Books and Art. I don’t know who produced it. It was a sort of popularly presented magazine. But I used to get this regularly, or have it sent to me; it was about what was going on the immediate arena, and I wanted to get into that arena.

Was Keble churchy still, when you were there?

None of its past was known to me when I went up for the entrance exam. Colleges were grouped together so you didn’t necessarily choose an individual college. I ended up at Keble possibly because that was the least discriminating one in my group. It was only when I got there that I realised it was one of the Victorian colleges and was associated with the Oxford Movement. It was changing then anyway, turning into a more hearty, sporting kind of establishment.

Did you have any kind of religious upbringing?

Well, I don’t want to labour it too much, but we went to Sunday school and church. Indeed I briefly became a Sunday-school teacher in my adolescence.

Did you believe what you were teaching?

Well, yes, I guess at about the age of fourteen I did.

Were you Anglican?

No, Congregational. My mother, who was responsible for our religious upbringing, went to whichever church was nearest. I don’t think we went to any church at all to begin with, but when my father died the first clergyman to come round was the Congregationalist, so we were at once turned into little Congregationalists.

And you took it seriously, I mean seriously enough to . . .

No, it was just that if you went along to church often enough you got recruited . . . It wasn’t that they detected any special holiness in me or that there was any to be detected. Going to church was habitual; it was part of what one did. It has to be said that support for my mother in her widowhood, interest in her, came from the church.

Your scientific brother, did he go along too?

Yes, he was dutiful. Whatever gets you through the night was his general philosophy of life. He already had his bedside manner.

So you had begun another magazine at Oxford, before setting up the ‘Review’?

The Review was started to cope with the aftermath of this magazine called Tomorrow, the one that published the Pinter play. The tendency for me was to start another magazine in order to reassure the printer that I hadn’t really gone out of business, that he would be paid eventually. OK, the magazine I handed to him (the Review, No. 1) had another title and two years had passed since the last time I’d given him anything to print (i.e. Tomorrow, No. 4), but he agreed to do it. He was still hoping to get paid for the Tomorrow work – and was paid for it, in the end.

You must have cut some kind of figure in Oxford, among the more literary undergraduates anyway.

To the extent of putting out this magazine. But nothing else worthy of note.

You’d produced a play.

Yes, and put on poetry readings to publicise the magazine. I was scurrying around the place, a sort of busy bee.

I’m not suggesting you were some foppish, would-be West End theatre figure like Kenneth Tynan. When you started ‘Tomorrow’, though, you must already have had a group of collaborators and contributors you could nobble for the next issue.

I’d enjoyed bringing out the Scorpion and had always remembered it. Then I met a Sri Lankan, Susil Pieris, who was very keen and I think he coedited the first two issues of Tomorrow. Then he got fed up or drifted away. It began, however, with my feeling that I wanted to start a magazine. Which is a terribly easy thing to do, really. At school, what I had done was to go round the houses trying to make people in Darlington buy it. And I had an army of schoolfriends to sell it. We’d all meet in some coffee-bar and I’d hand out copies and it was go, go, go, knocking on Darlingtonian doors, being told to clear off mostly, but every so often someone would buy the thing. A lot of this was going on in those days. The figure of Jon Silkin, for example, would arrive in Oxford with copies of Stand in a holdall and he would go round the colleges and people would condescend to him dreadfully. His forbearance and patience as he went about trying to sell it used to impress me. So I started this rather awful magazine Tomorrow. I suppose issue No. 3 wasn’t too bad. And then I ran out of money to pay the printer. It wasn’t selling any copies: 200-250 copies would seem a pretty good figure but the printer’s bill was £250-300 and I just didn’t have the money. The printer was a good chap and would wait for his money, but eventually he had to be paid. So the Review – in 1962 – was partly initiated by my need to pay the printer of the failed Tomorrow. Now that wasn’t at all the motivation of somebody like John Fuller, a literary friend who liked small bits of Tomorrow and was sympathetic to the idea of a new magazine. John and I didn’t sit around discussing subscriptions: we talked about poetry. He didn’t want to be centrally involved in the management. I think he already thought I was a dodgy figure financially and took two steps backwards on that score, for which I don’t blame him. There was no one else at the centre of it, carrying the can. He wanted to be friendly, engaged, but not finally culpable.

Were you sole editor of the ‘Review’ or was John Fuller a coeditor?

No, I was the editor. We had a committee consisting of John Fuller, Francis Hope, Martin Dodsworth, Colin Falck, Michael Fried and Gabriel Pearson. We never had meetings or anything like that. There was a lot of correspondence, because John went to Buffalo for a year. So he wrote to me a lot from there. And Michael and Colin had already left Oxford and gone off to London, where they shared a flat. Michael, a young American poet, was a big influence on me at that time. Very few members of the committee were around in Oxford, although the thing was based in Oxford.

How did you come by Colin Falck?

Colin was brought in by Michael. He was a celebrated figure in Oxford, having, I don’t know, got numerous degrees and acclaim for his writing, intelligence, and general wondrousness. So one had heard about this guy and Michael got friendly with him, how I don’t know, and they became a sort of duo. Colin became very active on the magazine. He shared a lot of Fried’s views. Looking back, I think they offered a counter-balancing presence: Fried and Falck represented the Romantic interest; Fuller and Hope the Augustan. I suppose I was halfway between. The two groupings hardly ever met; in fact, I don’t think Colin and Michael ever met John Fuller. But there were lots of letters from both sides. Dodsworth was more inclined to the Fuller side of things but not in any vehement way. Pearson was always slightly more inclined to the Falck side of things.

How did you come across Pearson?

I’d heard of him, and read things by him. He used to write in the New Left Review. I think he was already teaching at Essex University by then. He was again a known name and he knew something about modern poetry. The committee was very much a nominal sort of thing; they were friends of the magazine. I think Martin Dodsworth bailed the magazine out once with some money, a small amount at the time, but it saved the day. He became disaffected later, may even have pulled out, possibly because of the activities of Edward Pygge, our resident humorist. Not a figure a lot of people went for. John was very keen on Edward Pygge, who wrote a regular satirical column and became quite well known. John did one or two of the Edward Pygges, as did Colin. I did several. Michael loved it, thought Pygge was outrageous. Pygge attacked everybody, mercilessly.

I remember a very funny take-off of Geoffrey Hill. Written by you, I believe. It was called ‘The Hallstein Gospel’. An accompanying note claimed it had been found on a crumpled scrap of paper outside the poet’s window. He had discarded it, the note said, because it was ‘too cravenly comprehensible’.

Eventually Edward Pygge became a celebrated personage on whom someone is now writing a thesis. Tomorrow hadn’t had any of these fun and games. It was a pretty feeble operation. Only in the third issue had it started carrying reviews. By 1962 I was reading more, finding my feet. I read a lot of poetry, started writing it, and then I met Michael Fried. So with the Review there was a real reason for us to start a magazine. Tomorrow stopped in 1960 and the Review started in 1962.

A couple of years in which to do some growing up.

And I was no longer an undergraduate, so it was a lot more risky: starting a magazine instead of getting a job.

I was just going to ask what you did for money.

I used to teach English to foreign students. My landlady, Mrs Rose, had a dynamic, thrusting son, as he thought, anyway; dynamic and thrusting enough to be annoyed that I hadn’t paid the rent for the last six weeks. Without consulting me, he put an ad in the local paper on my behalf saying: ‘Oxford graduate gives English lessons.’ So I had these people knocking on my door in search of English lessons. Rose then got very enthusiastic and talked about setting up a language school. He needed somebody who had a degree on the letterhead and there I was up on the letterhead of Rose Educational Services or whatever: Ian Hamilton BA. Nothing came of that, thank goodness.

He didn’t end up running a chain of language schools?

No, he ended up publishing a daily information sheet about what was going on in Oxford, a freebie; it must have been one of the first of its kind.

Were you involved with the Fantasy Press?

Yes and no. The press as a poetry publishing operation, although it was pretty famous, had more or less stopped. It had published big figures in the 1950s: Larkin; a hardback of Thom Gunn’s Fighting Terms. It was all done by Oscar Mellor, a painter and photographer and, possibly, a pornographer. I think I might have gone to see him, knowing this connection with poetry publishing, to ask him about design or something. Anyway, we became friends. I lodged in his house for a bit. He was last heard of in Exeter. He was an odd figure.

He was mentioned in your Festschrift.

That would have been in Peter Dale’s essay. Oscar published a pamphlet of Peter’s. I never worked out how interested he really was in poetry. Donald Hall says that he was more interested in drinking beer than in poets. How old would he have been then? Must have been in his thirties. I never thought Oscar had opinions; he would just stroke his beard and smile.

Who decided on the minimalist layout for the minimalist poems in the ‘Review’?

They were set in Gill Sans typeface, as a tribute to Geoffrey Grigson’s New Verse. I think it was John Fuller’s idea. And it looked rather horrid. For some reason the first three issues were trimmed down in size, too; but issue No. 4 we printed in ordinary Times Roman and also went back to a more traditional format, eight inches and a bit by five and a bit. I’d got an appallingly bad degree from Oxford and had no prospects. I’d been expected to do much better than that. The idea had been that I would do postgraduate research. Much to the irritation of the people who’d fixed all this up for me, I proceeded to get a third.

How did you manage that?

By not doing the work, particularly the Anglo-Saxon.

I’d have thought you’d have winged it, given the general standard of undergraduates.

I think I was overrated by these people. I just put on a show for them in writing essays. But really I was ignorant.

Who were your tutors?

John Carey was one, in the last two terms. I wish he’d been my tutor all through, then maybe none of this would have happened. He was a breath of fresh air after the chap I’d had before who died, an old-time Oxford don.

Did you kill him?

What – with boredom? No, no, he was sort of steadily dying; he did quite a lot of semi-dying during tutorials. He had a wonderful gift of falling asleep as soon as you started reading an essay and, when you’d finished, of waking up and saying: very good, next week you will do Byron.

Are we allowed to know his name?

No, no. He wrote one book about Oxford and that was about it. But he was a thoroughly sweet, nice chap; he was very old. And he had the gift of being able to fall asleep and to wake up on the dot just as you finished. You could probably have read the same essay over and over every week – well, probably not. He probably had some subconscious way of knowing. I didn’t try it out. But I liked him. Then came Carey, a young Fellow full of life, vigour and ideas, clever as hell, and made it all very interesting. Carey thought that I would do well and suggested I write some thesis or other. I can’t remember what about. I’d have had to stay on. I thought why not?

They would have paid you.

There were grants in those days. But there I was, with my academic career in ruins – which didn’t entirely distress me: I wasn’t cut out for academia. There was, though, the question of how to survive. So I started a magazine.

Was it then that you came down to London?

No, most issues of the Review were from Oxford: 1965-66, I came to London. I’d been married since 1963. I got a job with the TLS and was directing the Cheltenham Festival. I commuted from a cottage in Didcot, not far from Oxford, where we were living; but that all fell to pieces and then I moved to London.

It was through meeting Arthur Crook at the Cheltenham Festival that you got the job with the ‘TLS’?

Not entirely. That meeting firmed it up. Alexander Cockburn, who’d been at Keble and whom I’d known at Oxford, was working at the TLS and we’d carried on seeing each other. I’d done a few reviews for him. Anyway, Alex had talked me up a bit and then I met Arthur. And there was a job vacant because Derwent May had gone to the Listener.

It was about this time that we met.

That’s right. I can’t remember when, in somebody’s kitchen.

Oliver Caldecott’s. He was a publisher, also an ex-South African. You were half-asleep on a sofa. You nearly fell off it when I said I knew and liked the ‘Review’.

Well, one didn’t often bump into a reader. It was fairly, you know, hand to mouth.

By this time you were writing the poems which you later collected?

I was writing poems and I’d got the job at the TLS. Once I’d moved to London I ran the Review from the flat in Paddington.

How did the connection with Al Alvarez and Donald Davie come about?

They were older by some eight years, well-known metropolitan figures. Al was the Observer poetry editor. And he’d printed some of my poems and some of Michael Fried’s, and he’d come to talk to the Oxford Poetry Society. He was a hero figure – of a sort. He’d brought out, in 1962, the Penguin New Poetry anthology. It’s hard to imagine it now, but being on the Observer, he was in a very influential position. There’s no regular poetry reviewer in the Observer now, is there?

Don’t they review poetry?

Oh, they do, but there’s certainly no central figure there who could wield Alvarez’s sort of authority. Anyway, he was known to us. On the whole, of all the metropolitan figures, he was the one we had time for. He wrote well and wasn’t tempted to like everything put in front of him and he got tough on some people we thought he should be tough on. When we decided to start the Review we had the idea of featuring Alvarez. It so happened that Donald Davie had just written an article in the Guardian called ‘Towards a New Aestheticism’ which was all about the imaginary museum and implied a rejection of emotional content in verse. Al took exception to this line. So we organised a dialogue between them. When you read the conversation that ensued you find that they end up agreeing over a Robert Lowell poem, ‘For the Union Dead’. It was agreed by both to have emotional content but also to have a sort of marmoreal shapeliness.

Well, it is one of Lowell’s best poems. Was the dialogue edited much?

No, we let them be as they were. And I think that’s the way it comes across. So there was this huge printed discussion and it got a lot of coverage and that launched the magazine. It was taken up in a TLS editorial; there was also a big Guardian piece about it, by Bernard Bergonzi. I’ve lots of cuttings; at that time I used to keep cuttings. In the next issue there was a long essay by Colin, ‘Dreams and Responsibilities’, about Al’s New Poetry anthology which was as near to a manifesto as the magazine ever had, and a very good piece.

You published your own poems in the magazine? To begin with?

We published pamphlets. One issue, 13, consisted of three pamphlets, one by me, one by Michael, and some translations by Colin. And they came packaged in an envelope. So that was my first appearance in book, well, pamphlet, form. But I’m not sure if I published my own poems in the magazine.

Subsequently other people became stalwarts of a kind, didn’t they? Hugo Williams?

Oh, they came in. David Harsent was another.

Peter Dale?

I think we published some of his poems. He never became quite one of the gang. There was a certain amount of indecision about him then. David Harsent appeared from nowhere. I think via the TLS. I was quite well placed by then, with my job at the TLS. I was doing the two editorial jobs simultaneously.

You were the poetry editor at the ‘TLS’?

Yes, and later I took over from Al at the Observer. There were lots of protests about my –

Omnipresence. Ubiquity.

– Yes. And quite right too. Except of course it seemed to me that this was completely all right; the more of me the better for the good of the cause, so to hell with these sniping charlatans and so forth. That was my position then, you understand.

Can we talk now about the poems you yourself were writing, in the midst of all this activity?

Well, we’re now in the period up to the early 1970s. The Review ended in 1972, the New Review began in 1974. I had published a book of verse with Faber, The Visit, in 1970 and had come to see myself as a writer of poems, which I hadn’t really done up till then. So that’s the period which ends around 1972, when I began to dry up. The poems weren’t coming, or nothing good was coming, and it was all much more intermittent. Before it had been something I did a bit of every day and felt confident of. I lost that in the 1970s. Does one write poems or not? – it became a question. Before they had been central to everything I did; indeed, you could almost say that the magazine and some of my reviewing were a way of clearing the ground for my own work, as criticism so often is.

Can you say something about your poems being so preoccupied with grief and loss, and the suffering brought to you by the suffering of another person? I’m thinking especially now of your first wife’s illnesses.

Well, obviously, that was a fact, her plight.

But it wasn’t exclusively hers. It had become yours too. What do you see as the connection, if indeed you do see a connection, between the brevity and concentration of the poems and their preoccupation with pain?

The brevity of the poems? Oh, well, that was just the way it worked out. I mean some of those poems are longer poems broken into two because they weren’t well glued together; there was nothing to join them properly together. It wasn’t a strategy, brevity, if you like, just a technical –

A technical device?

– How much you could get into a short space. Once you’d decided to concentrate on the dramatic ingredient you had to narrow the backcloth. I didn’t go in for a sort of Empsonian compression, making one thing stand for several at once. It was more a sense of emotional pressure, a claustrophobia, that I wanted to convey. I suppose I could only – in life – sustain that for a short time. And I turned it to my advantage in my verse or tried to. I did try longer pieces but they didn’t seem to work.

You are saying, then, that the fact that the poems were so preoccupied with pain, with suffering, meant that they had to be compressed? That the feelings demanding poetic expression demanded brevity too?

That’s certainly true. I think it does go back to my father when he was dying: the sense of being involved in someone else’s suffering while being helpless to do anything about it. And from that came what amounted to a belief that what a virtuous life would be about would be caring for somebody else. My mother made all of us feel very responsible for her welfare after he died. Perhaps ahead of our years we were made to feel that we had a ‘job’ to do in terms of looking after somebody and making sure they were OK and surrendering some of our own juvenile wishes for the sake of this person. She’d been left on her own with this terribly hard life. We had to contribute in some way – not financially – she was making an extra sacrifice in keeping us at school. She could easily not have done that. That was our feeling. And then in my marriage it became clear that I had married a sick person, a person who was going to be sick repeatedly and probably for ever, and so there was a continuity with what I had felt throughout my adolescence: this was what life’s about. And with that maybe came the wish for a controlled structure: you had to keep your control however bad things were; you had to be in charge. And I suppose the perfect poem became something that had to contain the maximum amount of control – and of suffering. Preferably it wouldn’t be about me; rather, it would be about my inability, however intensely I felt, to do anything about the suffering, because there are certain situations in life you can’t do anything about. One didn’t want, on the other hand, to sound wimpishly hopeless about it.

Or Jesus-like?

No. So a certain toughness of response had to come into the vocabulary.

And into the rhythms.

But none of this was thought out at the time. It’s only now, well, not only now, but about ten years ago, that I could see that there was a pattern in my life, as one does – that possibly I exist or only feel I exist when I am called on to serve or assist or something. Otherwise I don’t really have a personality, an existence.

And what about happiness? . . . Ah . . . Oh, I think that’s an idea you’ve given up on, essentially. You know it exists but you’ve been made to sacrifice it. You’ve been made to trade it in for this later thing, this feeling of conscientious service, which possibly gives you happiness; I don’t know, I hope it doesn’t. And you must always be suspicious of making poems out of suffering which is someone else’s. As that suffering person can be among the first to point out.

I remember your saying some time ago that Gisela, your wife, brought up your poems as a kind of accusation against you.

Well: you drive me mad so as to write poems about me. It’s the sort of thing a mad person might say. Anyway I don’t particularly want to talk about this.

How do you explain the relationship between the need to be in control you speak of and your feeling that the poem itself is a kind of summons which you have to obey? That it doesn’t arrive when you wish it to but on its own terms? ‘It’ comes to ‘you’; yet you have to be in control of it? Is there a contradiction here? How does it work?

The ‘it’ you imagine out there to be discovered by you, or that will visit you, with its mixture of passion and control, is a poem of perfection. So you listen out for the poem, if you like, and you imagine it. It’s as if the poetry you write is what you don’t seem to be able to express in your ordinary day-to-day transactions. There’s a sort of platonic realm of discourse that you occasionally manage to tune into. That is the impulse behind the poem – to be able to say in the poem what ordinarily doesn’t and cannot get said or understood or listened to.

And that couldn’t be said in any other way?

No, not in any other way. It is the perfect thing to say to this person at this time. Even if the person’s dead, there remains a perfect way of saying it.

So you were and still are inclined to despise poetry that doesn’t have such an exclusive and demanding conception of itself. How did you manage to combine that with your job as a metropolitan man of letters? With being Mr Manager, busy running the poetry side of the ‘TLS’ and the ‘Observer’. Wasn’t there a problem –

Oh, then I regarded it as a cleaning of the stables. You clear the ground in which the poet comes up and might be allowed to flourish, and you wipe out the enemy. In order for the true thing to be heard, you suppressed the untrue thing, destroyed it. It was warfare. Any literary-political weapons I could summon to my cause, I summoned.

A Poundian view of the battlefield.

Yes. Well, there was some fellow-feeling there. We felt that ‘they’ had to listen to this. But who were ‘they’? I was never quite sure who they were . . . Meanwhile the enemy was gaining ground in all sorts of ways. I saw myself protecting poetry against the pretenders, the charlatans, the fakers.

And the crowds that were taken in by them.

I had no interest in an audience. I mean the audience could be very few – as few as two dozen, as long as they had got it right. I didn’t want an audience that got it wrong. Who would want that? You might as well become a pop singer, or Roger McGough. My feeling was that we had something to protect. I’ve lately come to think that there are these two types of literary intelligence: the protective, the kind which safeguards art against a vulgarising audience, and the kind that takes art to an audience and tries to civilise that audience. The protector and the teacher. I would think of Melvyn Bragg, for instance, as a teacher. He takes what there is and makes it available. I think he feels the importance of that role quite strongly. There are those who are outward-turned and those who turn inward and in truth despise the audience. They want to protect art from the audience, the only audience art usually has – i.e. people who do not know what it is. I used to feel much more affinity for artists and poets of the past than for any living ones, apart from two or three friends, my own contemporaries. I felt I was looking after their interests to some extent. You can imagine what Arnold would have said if he had read Roger McGough.

And what might he have said about Melvyn Bragg’s sort of thing? There’s a famous bit in one of Henry James’s essays where he says that the trouble with periodical publication is that it’s like a train that has to leave the station every hour, according to the timetable, and if there are no genuine passengers then you have to put in dummies, so that the train will look full.

Like the dummies that get put in the magazines? Well, with the Review I wouldn’t think –

No, but we’re also talking about yourself as a general poetry manager at journals like the ‘TLS’ and ‘Observer’. As Henry James’s stationmaster, in effect. The ‘Review’ was different: it was your own private, jealously guarded place.

Well, the pages of the TLS I was in charge of also bear witness to much of was I up to. Remember that the TLS was all anonymous in those days. I think my record will stand up. At that time my feelings were so vehement . . . I was in my twenties. That sort of fervour began to dissipate a bit later.

It’s interesting that the vehemence you speak of, which started with your encounter with your English teacher in Darlington, never led you towards the Leavis camp.

A lot of people, particularly at Oxford, have said that that’s what my tendency really was. I never thought so because there were so many things Leavis said that I thought were rubbish, particularly on modern poetry.

You mean his admiration for Ronald Bottrall.

Yes, I’m no Ronald Bottrall fan. I remember turning down his work at the TLS. According to a recollection of David Harsent’s, which I have no memory of, on one particular evening I came to blows with Bottrall.

You were pretty cool about Empson too in your ‘Poetry Chronicle’.

I remain cool about Empson, apart from three or four poems which are uncharacteristic. I think he’s just a clever clogs. A show-off. Most of it doesn’t give me any pleasure at all, or if it does it’s a crossword puzzle kind of pleasure.

Even in the crossword puzzles, though, he has some compelling lines. Rhythmically compelling, among other things.

He’s very good at starting poems off and then not knowing what to do with them. Even in good poems like ‘Missing Dates’ there are whole stretches like ‘bled an old dog dry yet the exchange rills . . .’ What is he talking about? But then there is: ‘The waste remains, the waste remains and kills.’ You know what that means . . . As for Leavis, he was always a problem, that degree of vehemence and seriousness, and yet he got so petty, Cambridge and all that stuff. But there was something in him that stirred one.

When he wrote about verse that he admired –

In the end he just chickened out of modern poetry. I don’t think he was interested in it. Apart from Bottrall, who’s the mystery of mysteries. Post-Auden I don’t think he passed judgment on any poet. We don’t know what Leavis thought of Empson.

He did write about Empson initially. With much approval. In ‘New Bearings’ he speaks of the metaphysical mode he finds in the Empson poem ‘Legal Fiction’: ‘Law makes long spokes of the short stakes of men . . .’

All right, but we don’t know what he thinks of Dylan Thomas.

No, but one could guess. In spite of yourself and your own vehemence, your circle of reviewers and contributors widened, didn’t it?

It became a problem when I moved to London, and started meeting people. It’s probably why I stopped reviewing poetry in the Observer: I started meeting people, some of whom I liked, who hadn’t written very good poems, and I said so. So I lost friends that way, as one would. I was short of friends. Very few friendships can survive your saying: ‘I like you but I don’t like your poems.’ Much better to say: ‘I don’t like you but I like your poems.’ Yes, that would have been OK.

Douglas Dunn was one of the new contributors to the ‘Review’?

Yes.

And Clive James.

Clive gave the whole thing a bit of a lift. I picked him up from a piece in the New Statesman about Ezra Pound. It was very lively so he was recruited.

He wrote on Elizabeth Bishop and Richard Wilbur for the ‘Review’. And on Lowell?

No, I don’t think on Lowell, but he wrote well on those two and others. He wrote various things in the later issues. I’d certainly moved to London by then. We’d published about, I don’t know, ten or twelve issues by the time Clive appeared. But he was a mainstay of what I think of as the second wind of the magazine. The magazine continued on and off for ten years. Originally it was supposed to be bimonthly but there were gaps, well, money-induced gaps, but it produced 30 issues in ten years.

Almost a quarterly. Did you get a subvention from the Arts Council?

Latterly, but it was a pretty modest sum and still left me with a lot to do. It ran almost entirely on subscriptions.

What was the largest number of subscribers it ever had?

I can’t remember. Not much more than a thousand, I would think.

That seems to me quite a lot, really.

Well, there were a lot of libraries. Once libraries start to subscribe they don’t stop. But it was all done domestically, addressing, licking stamps, tying up parcels, trudging to the post office, keeping the subscriptions going. Sometimes just getting the money for the postage was a problem. You’d finally have the issue together, you’d conned some printer into printing it, and you couldn’t shift it to your loyal subscribers because you didn’t have the money for the stamps. Money was always very short. It left, all these things do, it left a trail –

Of disorder, strained printers, strained relationships?

My technique, as I’ve said, was to start another magazine when things got hopeless.

What bearing do you think the sense of obligation towards poetry that you’ve spoken of, your defence of the kind of poetry you most admired, the sacrifices which you felt you were ready to make for it: what bearing does all that have on the feeling of obligation which you’ve also alluded to, which was borne in on you during your childhood – the conviction that a virtuous life would essentially consist of being of service to others?

I think you define what you are by what you do. But yes, if you are going to do anything at all you do it for the benefit of what it is, and if ‘it’ happens to be poetry, which it happened to become for me, then there’s only one way to do it. There didn’t seem to me to be any choice in the matter. There’s no way to be quite a good poet. You either have to do it totally or not at all. Choosing not to do it at all I can understand. It’s not as if I wanted everyone else to be doing this. It’s just that that was what I happened to find myself doing. So either I must stop altogether, pull out of the whole deal, or do it in the way I did.

Now for a different kind of question. What about power?

Oh, power comes into it.

I’m thinking of social power. Look at the Festschrift for your 60th birthday. Again and again the contributors write of you as a sort of capo, the gaffer, the boss.

They’re all poetry people.

No, they’re not. They’re all writers, true, but there are non-poets among them. You must know what I mean. That is the role they all ascribe to you; the role they saw you taking up.

Well, it happened that way; but then it had to be like that if I was going to take the line I took. And then it turned into a manner, I suppose. You mean there was a sort of demagogic streak in what I was doing? There was certainly a wish to run things.

Exactly.

You know the way things were bloody well going to be. That was certainly there from the beginning and continued. It’s all because they wouldn’t let me play football.

Oh dear. You sound like that poem by Stephen Spender, telling the world how scared he was of the rough boys who threw stones.

Please don’t. I’d better shut up.

You could have been a contender. My point is you did become a contender.

In a way, yes. I’m still pretty good at football, except I’m a bit knackered these days. But you should see me watch football. I watch it really hard, give myself a very hard time.

There’ve been no further repercussions of that childhood heart murmur you mentioned?

It went away as soon as I started drinking.

You said a few minutes ago that there’s no point in trying to be quite a good poet: you either have to mean it totally, or not at all. And now the same thing goes for how you wanted to run things. It had to be in your own way. But you found it a problem to do so – living in London and working on the ‘TLS’ and reviewing people you met, people you liked, who had written poor poems.

It isn’t true that that happened when I moved to London. It was really much later that I started losing my edge as a reviewer. I’d been in London for some years. I carried on doing that in the TLS and the Review, wielding the axe on all sides. A bit later, some time in my thirties, I began to cool down.

Did you cool down because you had lost some of your literary conviction, the belief that the difference between good and poor poetry is a vital one; or because you had just lost energy?

Well, I certainly hadn’t lost that conviction. I might have lost the feeling that one could win. And somehow it had all become an uphill and hopeless task. It kept on coming, this bad stuff. And also the whole pop poetry phenomenon by the end of the 1960s and in the 1970s was gaining ground, so that one felt one was being pushed into this rather marginal, rather ‘academic’ sort of pigeonhole.

Except that so many academics were rushing after the other kind of stuff.

Oh, palefaces and redskins, all of that. Yes, one was very much out to be a paleface but the redskins were winning. One became less interested in destroying the opposition and more in nurturing the things that one had faith in. You just got on with believing the real thing still to be important, but not that you could trounce the opposition or even that it was important to do it. What did become more complicated was that there were some instances when I knew I was pulling my punches in a way that I wouldn’t have done if I didn’t know the people involved. As soon as that began to happen I thought it was time to stop. It had to be so, because that was the attitude the Review used to attack . . . you know, the sight of people giving their friends a leg-up and so on. It hadn’t exactly come to that with me, but it was getting perilously close in some ways. And also the people who were writing for the Review were now all writing in the Sunday papers, and the Guardian and all the rest of it. They were running the show, in a way, but it didn’t seem to make any difference. It seemed to me that there were now two areas: one was that of what you might call highbrow poetry – the poetry reviewed in the Guardian – and one could go on belabouring people writing in that field. But outside it was another area where poetry had formed an alliance with pop music and the whole business of the 1960s scene, which had nothing to do with poetry. However, some spark at Penguin Books filled an anthology with these people and pretended that they were poets. Then I would get annoyed again; but after a bit there was nothing I could do to stop it. It wasn’t poetry. It was self-evidently not poetry. But it was something, and it was something that in its way did work, and it was only when people tried to pass it off as poetry that I felt it was my business to have anything much to say about it. And that eventually became my position.

What you said about meeting people a moment ago reminds me of a letter Orwell wrote to Stephen Spender saying that when he didn’t know him it was easy to use him as an example of the kind of people he disapproved of – the ‘Pansy Left’ etc. But now that he’d met him and had found him agreeable he just couldn’t do it any more. So here was Orwell, famous for being a flinty man of integrity, in effect throwing in the towel.

Well, quite. It’s a kind of fatigue also. Battle fatigue. It made no difference and you spent far too much time on it. And also you lose interest. The new bad poet is 21 and you’re 33, this seniorish sort of figure, working on the TLS and so on. So things altered and I lost interest in the day-to-day fray. Early on, it was always a bit of a laugh to turn these people into grotesque caricatures – which, again, is easier to do if you don’t know them. Edward Pygge could write about Adrian Mitchell’s Semen for Vietnam Appeal in the Review, but when you met Adrian Mitchell, he was a perfectly nice chap and all that. Not that I knew him very well or know him now. I can well imagine that if I did it would be difficult to portray him as a grotesque. And there were people who made it their business to get known around the place and be agreeable and liked and so on.

The ‘Review’ never nurtured any of the people who became big names: say, Ted Hughes?

He predated it. They all did. Ted Hughes had a reputation by the end of the 1950s. So, too, did Thom Gunn, Philip Larkin. There was nobody new worth nurturing apart from the people we published in the early 1960s.

Was Plath already out?

Plath died in 1963, a year after the first issue of the Review; and we devoted a whole issue to her final poems and would certainly have printed poems by her. She’d already had a book of poems out and a novel. I would have regarded her, Hughes, Larkin and so on as being from an earlier generation. Larkin was even earlier.

They were the established figures.

Very much so. I’d read them at school.

What about people who came later on: Seamus Heaney, say?

I reviewed Seamus Heaney’s first book somewhat unfavourably in the Observer. Not unfavourably, I could see he was quite good but he wasn’t that special and I said so. There’s a mocking piece about him somewhere in the Review. He was around; you know, this Irishman people were talking about. There was an Irish thing developing under the auspices of Philip Hobsbaum, who’d been a prominent member of another outfit called the Group, whom we were committed to attacking. Hobsbaum had taught in Belfast and then went on to Glasgow. But prior to that he was in London and he was a prime mover in the Group, he and Edward Lucie-Smith. We attacked them all the time. They were enemies. A lot was going on that we were in opposition to: there was the Group; there was pop poetry; there was the Liverpool Scene. And when Lucie-Smith, arch-organiser of the Group, went off and edited a book called The Liverpool Scene, praising those people to the skies we thought: ‘Treasonable clerk. This is the sort of thing you’d expect from these corrupt, opportunistic, careerist-type figures.’ So we went at them. As for nurturing talent, the talent that was around we . . . nurtured. It was far more substantial than anything else that was there. Including Belfast. Heaney’s first book didn’t come out until 1968. The Review started in 1962. By 1968 the Review was almost over. Heaney had published a pamphlet in a series called, I think, Festival Pamphlets, which Philip Hobsbaum used to organise. I seem to remember seeing that pamphlet and thinking they were OK, these agricultural musings, they were not bad, but nothing special.

Do you still feel like that about Heaney?

I admire him from a distance but I still don’t get greatly excited by his work and I’m still somewhat puzzled by his phenomenal success. On the other hand, I can see he’s gifted and interesting. I find it very hard to quote a half a dozen lines from him in the way I would from any favourite poet of mine.

Well, it’s always said that one of the tests of a poet is memorability.

It’s certainly one of my tests. Seamus has kind of failed it. That may not mean anything.

What about someone like Geoffrey Hill? I’ve mentioned that Edward Pygge made mock of him. Was that as much as you were bothered to do for him?

I never had any time for Geoffrey Hill and still don’t. The only things of his I liked were in prose, the Mercian Hymns. Some of those are rather good. But I think he is so pretentious and portentous, obscure and grand-mannered. I don’t go with that. I never did. ‘Against the burly air I strode’. That was line one. Pretty much downhill since then, in terms of my taste for his work. No, no time for him at all.

Who else did you put forward in the ‘Review’?

We also had one eye on America, largely because of Michael Fried, and also because the impulse behind the Review came from the discovery that much more interesting things were going on in America than here. Poets like Roethke, Berryman, Lowell and Plath all seemed to be much more exciting than anything being done in this country. These were, if you like, our exemplars.

Very much the Al Alvarez line.

Al was a big influence. He shaped a lot of that terrain, at least for me, and possibly, too, for Michael. Michael knew Al so there might have been things toing and froing there I don’t know about.

Did you publish Berryman or Roethke?

Articles about them. Roethke I preferred to Berryman. I was never a great Berryman fan. By that stage he had not published any of his Dream Songs. Some of those got me interested but the poems subsequent to the Dream Songs weren’t very good. He was then rather safe, tedious. He’d written one rather weird poem called Homage to Mistress Bradstreet, which came out in 1959. One knew about that, it was odd and interesting, but I didn’t really know what it was about. But he was there. And he was also a terrific, mad, drunk person – as was Roethke. As was, so we heard, Lowell. As was Plath. All this had this air of being intense and exciting – intensely personal experience bearing in on these highly disciplined poems. The tension between formality and discipline, on the one hand, and powerful emotional content, on the other, was what we looked for in poems. And what we looked for in poems that came in to the magazine. Some of which were by people like Hugo Williams or David Harsent. It could be said that we didn’t find one single voice that then went on to assume a commanding position as, say, Seamus Heaney did. I don’t think we did. But I don’t know whether that really matters.

I wasn’t remarking on whether or not the fact is important; just that it is a fact.

If you looked at the period and tried to think of people we didn’t print who were contemporaries and at the same stage, in each case I would have known about them, probably, and made the decision not to. And there were literary-political elements, too, that mattered more than they should have, looking back. Like with the Group and the Belfast thing.

The ‘Review’ itself was a peculiarly masculine affair. Why was that? Were there just no women poets, no women critics?

There hardly ever are any women poets. It’s only recently that post-feminism has introduced the need to publish women poets, however good or bad. I don’t remember anybody appearing then who was strikingly good. If someone like that had appeared we would never have turned her down on the grounds that she was a woman. On the contrary, we would have had her in at once, if she was half decent. There wasn’t a misogynistic vein in the journal. Not at all. I could think of many women who were around, but they weren’t any good, in the same way that so many of the guys who were around weren’t any good.

And among the Americans, apart from Plath, was there no one?

We didn’t at the start really think very much of Plath. She’d only published one book of poems, The Colossus, which was a studied and derivative book we were not very impressed with and, in so far as she was influenced by anybody, we thought she was influenced by Ted Hughes. That influence was foisted onto these rather academic structures of hers; or so it seemed. But then, sure enough, when her last book came out, the work was greatly different from anything she had done before. They were extraordinary, some of them. So we thought yes. But where do you go from there? She was a one-off poet. She doesn’t seem to me to lead in any direction. One couldn’t see where one could go from there. It did fit with the things we were already looking for or which we already had found in Lowell, who was also in touch with the magazine. We didn’t like Anne Sexton; we thought she was a fraud, trying it on, trying to be Sylvia Plath. There were some miniature mad talents in America, you know, Plath-derived, but there wasn’t much of that here. And none of it was any good. There was one poet whom I thought very good called Thomas Clark, an American who was living in Colchester who was writing the sort of thing we wanted. We printed two or three of his poems. But then, blow me down, if he didn’t suddenly become Tom Clark objectivist, and start writing like William Carlos Williams. He went back to America and began writing objectivist poems dribbling down the page. I thought this is awful, a talent lost. Things were cropping up all over the place that one didn’t seem to able to do anything to prevent.

You had an issue devoted to Black Mountain.

It was part of an issue, No. 10, edited by Charles Tomlinson. It was done, as I think we said at the time, for historical reasons, but it didn’t seem to fit. It was the issue we printed the least of, as a feeble protest against doing it at all. But it became the most popular issue; it’s now the rarest issue of the Review.

How humiliating.

Yes. I was ashamed of that because it wasn’t what the magazine was about. We weren’t supposed to be telling people about fads. I shouldn’t have done it. I don’t think you’ll find any other traces of that neo-Poundian stuff in the magazine.

But Pound was somebody who interested you – he affected your own work. I mean the influence he had on you as an Imagist. Did you read his longer poems as containing little moments of Imagism, so to speak?

Far too few.

Did you read the longer poems?

Yes, I laboured through the Cantos at one point, with a heavy head. I just thought they were a big, big mistake, academic, a waste. So it’s the early Pound, while he was in London, who was of interest. It was his theorising, the organising ability, some of the combativeness, one or two of the poems, that we valued. The shorter poems, like ‘The Return’. And I did think that he had a wonderful ear, and still think so. Which again went to waste; so much went to waste in his career. On the other hand you can’t easily see what else he might have turned into. It’s almost as if there were two quite separate writers, as if the young Pound stopped and then this cranky person cropped up in his place.

I asked some moments ago what connection you see between the conciseness of your poems and their preoccupation with pain. Now I have a related question. In the poems you don’t disguise or fictionalise the people you are speaking about, but you do speak of them very cryptically. Your poems are intensely private and confessional, if that’s the word, and yet at the same time they are written as if to deny readers access to the donnée or actual ‘situation’ giving rise to the poem.

There is a reticence at work in the poems. I am expressing very private emotions as if to another person, but I have no right to make that person’s real-life suffering public, as it would be if the factual background to the poem were to be published. I am creating the dramatic illusion of speaking as if to that one person alone. That’s very different, say, from printing one’s letters to that person. There is a difference between giving voice to moments of intensity which have a sort of general interest or application and airing in public things which are essentially confidences. So the individual becomes blurred, as in most love poetry. The addressee is non-specific, the reader doesn’t need to know much about the person, even though the poem is framed as if addressed to her. You might know she is called Julia or something, but you don’t know a lot more than that. You probably know less about the relationship in most love poems than you would in a poem by me – a poem that tells you something about the basis of the relationship, the most intense point of the relationship. But my poems are also about something else. They are poems about loss, about transience, disappointed hopes, if you like, about protectiveness, the wish to alter something that cannot be altered, they’re about the conditions of an entire life experienced in this local and precise way. So, yes, a lot disappears of the confidential detail. I don’t think it would be right to have such detail in a poem anyway. You might in a prose narrative give the person a different name, use lots of details about them, and that might not seem improper. But that doesn’t seem to me to be what poems ought to be doing. They ought to deal with the intense, climactic point of a drama, the essence of the feeling it evokes. They should invite the reader to eavesdrop, you might say.

So the kind of poetry you were writing could only take the form of a direct address by the poet to another person?

Virtually all of them do. Either somebody is dead, or somebody is mad and can’t make sense of what you are saying.

But, after all, if you think of Donne, or Shakespeare in the Sonnets for that matter, there’s plenty of direct address; but you don’t get a sense of the reader as eavesdropper.

I think you do.

You do? I think of them more as staged affairs. Which doesn’t necessarily diminish their intensity.

Well, they were writing in the literary conventions of their time. I wanted to create the illusion of privacy, of an overheard thing. What one likes, or what I like, in poems is the feeling that I am overhearing, even though I know that I am not.

Donne is often stagy, in a contrived sense; Shakespeare much less so – certainly in the most compelling of the Sonnets.

Yes, Donne is tricky and ingenious and he’s enjoying his ingenuity. In Shakespeare you get the sense of a much more troubled spirit.

And so of a much greater degree of communion with himself and at the same time of engagement with the other person.

Something is at stake there. And has to be spoken of.