This last while I have carried my heart in my boots. For a minute or two I actually imagined I could be responsible for the spread of foot and mouth disease across Britain. On my first acquaintance with the hill farmers of the Lake District, on a plot high above Keswick, I had a view of the countryside for tens of miles. I thought of the fields that had passed underfoot, all the way back to Essex, through Dumfriesshire, Northumberland or Sussex. Later I would continue on my way to Devon, passing through other places waking up in the middle of the worst agricultural nightmare in seventy years. My boots are without guilt, but in all the walking here and there, in the asking and listening, I came to feel that British farming was already dying, that the new epidemic was but an unexpected acceleration of a certain decline.

In the last few weeks nearly 100,000 head of livestock have been condemned. The industry has lost £300 million. A freeze still holds on the export of livestock. Country footpaths are zones of reproach and supermarkets are running out of Argentinian beef. The Agriculture Minister, Nick Brown, is accused of doing too much and doing too little. The questions surrounding the foot and mouth epidemic – where will it all end? how did it all start? – might be understood to accord with anxiety about every aspect of British agriculture today. The worst has not been and gone. It is yet to come. Still, one thing may already be clear: British farming hanged itself on the expectation of plenty.

One day not long ago I was in the Sainsbury’s superstore on the Cromwell Road. Three of the company’s top brass ushered me down the aisles, pointing here, gasping there, each of them in something of a swoon at the heavenliness on offer. ‘People want to be interested,’ said Alison Austin, a technical adviser, ‘you’ve just got to capture their imagination.’ We were standing by the sandwiches and the takeaway hot foods lined up in front of the whooshing doors. Alison swept her hand over the colourful bazaar of sandwich choices. ‘This is a range called Be Good to Yourself,’ she said, ‘with fresh, healthy fillings, and here we have the more gourmet range, Taste the Difference. We have a policy of using British produce where we can. With carrots, for example, we want to provide economic profitability to the farmer, using the short carrots for one line of produce and the bigger ones for another.’

The Cromwell Road branch of Sainsbury’s is what they call a ‘flagship store’. It’s not only a giant emporium, it is also grander than any other store in the chain, selling more champagne, fresh fish, organic meat and Special Selection food. Six varieties of caviar are available all year round.

‘People are gaining more confidence in sushi,’ said Peter Morrison, Manager, Trading Division. ‘We have joined forces with very credible traders such as Yo! Sushi and we aim to educate customers by bringing them here.’ Alison handed me a cup of liquid grass from the fresh juice bar, Crussh. There was something unusually potent about that afternoon – the thoughts in my head as I tilted the cup – and for a moment the whole supermarket seemed to spin around me. People wandered by. The place was a madhouse of bleeping barcodes. ‘How do you like it?’ one of them asked. I gulped it down and focused my eyes. ‘It tastes like an English field,’ I said.

The store manager guided me to the cut flowers. ‘We are the UK’s largest flower sellers,’ he told me, ‘the biggest year on year increase of any product in the store is in flowers.’ The bunches before me were a far cry from the sad carnations and petrol station bouquets that now lie about the country as tributes to the suddenly dead. The ones he showed me had a very smart, sculptural appearance, and they sold for £25 a pop. ‘We have 40 kinds of apple,’ Alison said, ‘and again, we take the crop, the smaller ones being more for the economy bags.’

‘Someone came in on Christmas Eve and asked for banana leaves,’ the keen young product manager over in fruit and vegetables told me, ‘and you know something? We had them.’

You would have to say that Sainsbury’s is amazing. It has everything – 50 kinds of tea, 400 kinds of bread, kosher chicken schnitzels, Cornish pilchards – and everywhere I turned that day there was some bamboozling elixir of the notion of plenty. Their own-brand products are made to high standards: the fresh meat, for example, is subject to much higher vigilance over date and provenance than any meat in Europe.1 ‘Some things take a while,’ Peter Morrison said, ‘you can put something out and it won’t work. Then you have to think again, about how to market it, how to package it, where to place it, and six months later you’ll try again and it might work.’ We stopped beside the yoghurts. ‘Now this,’ he said, picking up a tub of Devon yoghurt, ‘is made at a place called Stapleton Farm. We got wind of how good it was: a tiny operation, we went down there, we got some technical advisers involved, and now look, it’s brilliant!’ I tasted some of the Stapleton yoghurt. It was much better than the liquid grass. ‘It’s about the rural business growing,’ Peter said. ‘Real food is what people want. This couple in Devon’ – he gestured to the yoghurt pots – ‘started from virtually nowhere. Of course they were nervous at first about working with such a major retailer. But these people are the new kind of producer.’

Passing the condiments aisle I saw an old man standing in front of the Oxo cubes. He looked a bit shaky. His lips were moving and he had one of the foil-wrapped Oxo cubes in the palm of his hand. ‘People go to Tuscany,’ Alison was saying, ‘and they eat Parma ham and they come back here and they want it all the time. So we go out and find the best.’ You are always alone with the oddness of modern consumption. Walking under the white lights of Sainsbury’s you find out just who you are. The reams of cartons, the pyramids of tins: there they stand on the miles of shelves, the story of how we live now. Cereal boxes look out at you with their breakfast-ready smiles, containing flakes of bran, handfuls of oats, which come from fields mentioned in the Domesday Book. And here you are in the year 2001 – choosing. We went over to the aisle with the cooking oils and Alison did one of her long arm-flourishes: ‘When I was a child,’ she said, ‘my mother used a bottle of prescription olive oil to clean the salad bowl. Now look!’ A line of tank-green bottles stretched into the distance. ‘Choice!’ she said.

Supermarket people like to use certain words. When you are with them in the fruit department they all say ‘fresh’ and ‘juicy’ and ‘variety’ and ‘good farming practices’. (Or as head office puts it, ‘in 1992 Sainsbury developed a protocol for growing crops under Integrated Crop Management System principles. Following these principles can result in reduced usage of pesticides by combining more traditional aspects of agriculture and new technologies.’) In the meat department there is much talk of ‘friendly’, ‘animal well-being’, ‘humane’, ‘safe’, ‘high standards’ and ‘provenance’. The executives spent their time with me highlighting what they see as the strength of the partnerships with British farming which keep everyone happy. ‘The consumer is what matters,’ said Alison, ‘and we believe in strong, creative, ethical retailing.’

Down at the front of the store again I put one of the gourmet sandwiches on a table and opened it up. The bread was grainy. The lettuce was pale green and fresh. Pieces of chicken and strips of pepper were neatly set out on a thin layer of butter. The open sandwich was a tableau of unwritten biographies: grains and vegetables and meat were glistening there, uncontroversially, their stories of economic life and farming history and current disaster safely behind them.

When I was a boy we had a painting above the phone table. It was the only real painting in the house, and it showed a wide field in the evening with a farm at the far end. The farmhouse had a light in one of the windows. The painting had been a wedding present, and my mother thought it was a bit dour and dirty-looking, so she did the frame up with some white gloss, which flaked over the years. I used to lie on the hall carpet and look at the picture of the farm for ages; the field was golden enough to run through and get lost in, and the brown daubs of farmhouse were enough to send me into a swoon of God-knows-what. I suppose it was all part of a general childhood boredom, and it meant nothing, but it seemed very heightening at the time. The painting raised my feelings up on stilts, and made me imagine myself to be part of an older world, where people lived and worked in a state of sentimental peace. All rot of course. But lovely rot. Sometimes I would come downstairs in the night and shine my torch on the painting.

At one time it seemed as if all the farms around our way had been abandoned or pulled down to make room for housing. Past railway lines and beyond the diminishing fields we would find old, dilapidated Ayrshire farmhouses with rusted tractors and old wooden drinking troughs lying about in the yard, and we’d play in them for half the summer. Cranberry Moss Farm, McLaughlin’s Farm on Byrehill, Ashgrove Farm, the Old Mains – nowadays they are all buried under concrete, except for the farm at Toddhill, which became a home for the mentally handicapped. In my youth they had been like haunted houses. There were echoes in the barns.

Those farms seemed as remote from the daily reality of our lives as the one in the wedding picture. We would never live there: computer factories and industrial cleaners would soon replace them as providers of jobs, and it was these new places, in our Ayrshire, that spoke of the lives we were supposed one day to live. We took it for granted – much too early, as it turned out – that farming was a thing of the past, a thing people did before they were sophisticated like us. We never considered the stuff on our plates; we thought the school milk came on a lorry from London. Never for a second did my friends and I think of ourselves as coming from a rural community; like all British suburban kids, we lived as dark, twinkling fallout from a big city, in our case Glasgow; and we thought carports and breezeblocks were part of the natural order.

But of course there was plenty of agriculture. It surrounded us. The farms had just been pushed out a wee bit – and wee could seem larger than it was, at least for us, shocked by the whiteness of our new buildings into thinking a thatched roof was the height of exotic. Everything changed for me with the discovery of Robert Burns: those torn-up fields out there were his fields, those bulldozed farms as old as his words, both old and new to me then. Burns was ever a slave to the farming business: he is the patron saint of struggling farmers and poor soil. But in actual fact, despite our thoughts and our recovery from our thoughts, in the early 1970s British farming was in a pretty good state. J.G.S. and Frances Donaldson’s Farming in Britain Today, published around this time, just before Britain’s entry into the Common Market, expressed the view that a beautiful balance had been struck.

Today agriculture is one of Britain’s most efficient industries. It has a controlled growth of 3.5 per cent a year, and in the last ten years its labour productivity has increased at twice the rate for industry as a whole. It supplies approximately 50 per cent of the nation’s food. Travelling through England today with its trim hedges, arable and ley farming, highly capitalised and intensively used buildings, it is hard to imagine the broken-backed appearance of yesterday.

‘Yesterday’ meant the 1920s and 1930s. But now, as I write, the situation of farming in this country is perhaps worse than it has ever been, and the countryside itself is dying. We are at a stage where it is difficult to imagine British farming surviving in any of its traditional forms; and for millions living on these islands, a long-term crisis has been turning into a terminal disaster.

Three years ago agriculture contributed £6.9 billion to the British economy, around 1 per cent of the Gross Domestic Product. It represented 5.3 per cent of the value of UK exports. The figure for 1999 was £1.8 billion. The total area of agricultural land is 18.6 million hectares, 76 per cent of the entire land surface. According to an agricultural census in June 1999, there has been a decrease of 5.3 per cent in the area given over to crops, as a result of a decrease in cereals and an increase in set-aside. According to a recent report from the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (Maff), the 1999 figures show a drop in the labour force of 3.6 per cent, the largest decrease in a dozen years. ‘These results,’ the Report continues, ‘are not unexpected given the financial pressures experienced by most sectors of the industry over the last few years.’

Farmers’ income fell by over 60 per cent between 1995 and 1999. Despite increases in production, earnings were lower in 1999 by £518 million.2 The value of wheat fell by 6.5 per cent and barley by 5.4. Pigs were £99 million down on 1998 and lambs £126 million down; the value of poultry meat fell by £100 million or 7.4 per cent; the value of milk fell by £45 million; and the value of eggs by 10 per cent or £40 million. A giant profit gap has opened up throughout the industry: rape seed, for example, which costs £200 a ton to produce is selling for £170 per ton (including the Government subsidy); a savoy cabbage, costing 13 pence to produce, is sold by the farmer for 11 pence, and by the supermarkets for 47 pence.

Hill farmers earned less than £8000 a year on average in 1998-99 (and 60 per cent of that came to them in subsidies), but late last year, when I first started talking to farmers, many were making nothing at all, and most were heavily in debt to the bank. A suicide helpline was set up and the Royal College of Psychiatrists expressed concern at the increased number of suicides among hill farmers in particular. A spokesman for Maff said that agriculture was costing every British taxpayer £4 a week. After Germany and France, the UK makes the largest annual contribution to the Common Agricultural Policy, and yet, even before the great rise in the strength of the pound, British farmers’ production costs were higher than anywhere else in the EU, to a large extent because of the troubles of recent years.

‘Everything is a nightmare,’ one farmer told me. ‘There are costs everywhere, and even the subsidy is spent long before you receive it. We are all in hock to the banks – and they say we are overmanned, but we don’t have anybody here, just us, and children maybe, and an absolute fucking nightmare from top to bottom.’ The strong pound, the payment of subsidy cheques in euros, the BSE crisis, swine fever, and now foot and mouth disease, together with overproduction in the rest of the world’s markets – these are the reasons for the worsened situation. But they are not the cause of the longer-term crisis in British farming: local overproduction is behind that, and it is behind the destruction of the countryside too. For all the savage reductions of recent times, farming still employs too many and produces too much: even before the end of February, when diseased livestock burned on funeral pyres 130 feet high, some farmers were killing their own livestock for want of a profit, or to save the fuel costs incurred in taking them to market.

In Britain nowadays most farmers are given aid – a great deal of aid, but too little to save them – in order to produce food nobody wants to buy.3 The way livestock subsidies work – per animal – means that there is an incentive for farmers to increase flocks and herds rather than improve the marketing of what they’ve got. As things are, subsidies save some farmers, but they are a useless way to shore up an ailing industry, except perhaps in wartime.

The evidence of what is wrong is out in the British land itself. It is to be found in the particularities of farming experience now, but also in a historical understanding of what farming has meant in this country. Farming – more even than coal, more than ships, steel, or Posh and Becks – is at the centre of who British people think they are. It has a heady, long-standing, romantic and sworn place in the cultural imagination: the death of farming will not be an easy one in the green and pleasant land. Even shiny, new, millennial economic crises have to call the past into question. How did we come to this?

In the 18th century, farmers were still struggling out of the old ways depicted in Piers Plowman, or the Bayeux Tapestry, where English farm horses are seen for the first time, bringing vegetables from the fields to the kitchen table. Jethro Tull, one of the fathers of modern agriculture, devoted himself to finding ways to increase yields – he invented the seed-drill, a machine that could sow three rows of seed simultaneously – and collected his ideas in The New Horse Houghing Husbandry: or, an Essay on the Principles of Tillage and Vegetation (1731). His ideas were widely accepted by the time he died at Prosperous Farm, near Hungerford in Berkshire, in 1741. Arthur Young, an agricultural educator and zealot of Improvement, set out in 1767 on a series of journeys through the country. A Six Months’ Tour through the North of England gives a spirited first-person account of changing agricultural conditions. ‘Agriculture is the grand product that supports the people,’ he wrote, ‘both public and private wealth can only arise from three sources, agriculture, manufactures and commerce … Agriculture much exceeds the others; it is even the foundation of the principal branches.’ But the new improvements came at a price and they changed for ever the relationship between the land and the people who tried to live by it. British peasant life was effectively over. ‘The agrarian revolution was economically justifiable,’ Pauline Gregg writes in A Social and Economic History of Britain 1760-1965, but ‘its social effects were disastrous. Scores of thousands of peasants suffered complete ruin. The small farmer, the cottager, the squatter, were driven off the soil, and their cottages were often pulled down.’ The British countryside, in the face of all improvements, and with every prospect of sharing in the coming wealth of nations, became as Goldsmith described it in ‘The Deserted Village’:

Ill fares the land, to hastening ills a prey,

Where wealth accumulates, and men decay;

Princes and lords may flourish, or may fade;

A breath can make them, as a breath has made;

But a bold peasantry, their country’s pride,

When once destroyed, can never be supplied.

In the spring of 1770 British cows were so disabled by starvation that they had to be carried out to the pastures. This business was known as ‘the lifting’. The General View of Ayrshire, published in 1840, records that as late as 1800 one third of the cows and horses in the county were killed for want of fodder. By the end of winter in this period, according to John Higgs’s The Land (1964), every blade of grass had been eaten and the animals were forced to follow the plough looking for upturned roots.

The social structure of the country had changed, the population had grown, the plough had been improved, the threshing machine had been invented, and crop rotation had taken hold. William Cobbett, in his Rural Rides – originally a column that appeared in the Political Register between 1822 and 1826 – captured the movements which created the basis of the farming world we know. Cobbett rode out on horseback to look at farms to the south and east of a line between Norwich and Hereford; he made an inspection of the land and spoke to the people working on it. He addressed groups of farmers on the Corn Laws, taxes, placemen, money for agricultural paupers, and the general need for reform.

In one of his columns he describes meeting a man coming home from the fields. ‘I asked him how he got on,’ he writes. ‘He said, very badly. I asked him what was the cause of it. He said the hard times. “What times?” said I; was there ever a finer summer, a finer harvest, and is there not an old wheat-rick in every farmyard? “Ah!” said he, “they make it hard for poor people, for all that.” “They,” said I, “who is they?”’ Cobbett yearned for a pre-industrial England of fine summer days and wheat-ricks, and yet his conservatism did not prevent him from becoming an evangelist of Improvement. As for ‘they’ – Cobbett knew what was meant; he later called it ‘the Thing’, and sometimes ‘the system’. He railed against everything that was wrong with English agriculture: low wages, absentee landlords, greedy clergymen, corruption; and he was prosecuted for supporting a riot by these same agricultural workers the year after he published Rural Rides. Cobbett saw how self-inflated governments could sit by and watch lives crumble. His discriminating rage has the tang of today. ‘The system of managing the affairs of the nation,’ he wrote in Cottage Economy, ‘has made all flashy and false, and has put all things out of their place. Pomposity, bombast, hyperbole, redundancy and obscurity, both in speaking and writing; mock-delicacy in manners, mock-liberality, mock-humanity … all have arisen, grown, branched out, bloomed and borne together; and we are now beginning to taste of their fruit.’

Rain was running down Nelson’s Column and Trafalgar Square was awash with visitors inspecting the lions. An American woman stepping into the National Gallery was worried about her camera lens. ‘This British weather will be the end of us,’ she said, as her husband shook out the umbrellas. In the Sackler Room – Room 34 – children with identical haircuts sat down on the wooden floor; they stared at the British weather of long ago, spread in oils with palette knives, and they, too, asked why it was always so fuzzy and so cloudy. One group sat around Turner’s Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway. The instructor encouraged them to express something about the atmosphere of the picture. ‘Does it make you shiver?’ she said. ‘It’s like outside,’ one of the children replied. But most of them were interested in the hare running ahead of the train. ‘Will it die?’ one of them asked. ‘Where is it running to?’

The future. You feel the force of change in some of these weathery British pictures. Over the last few months I kept coming back to this room, and sitting here, further up from the Turners, looking at Constable’s The Cornfield. We see an English country lane at harvest time where nothing is unusual but everything is spectacular. Corn spills down an embankment, going to grass and ferns, going to pepper saxifrage or hog’s fennel, dandelion and corn poppy, down to a stream. Giant trees reach up to the dark, gathering clouds. At their foot, a small boy lies flat on his front drinking from the stream. He wears a red waistcoat and has a tear in the left leg of his trousers. A dog with a marked shadow looks up and past him with its pink tongue out. The sheep in front of the dog are making for a broken gate that opens onto the cornfield. A plough is stowed in a ditch; the farmer advances from the field; and in the distance, which stretches for miles, you see people already at work.

The picture has philosophical currency: people will still say it is an important part of what is meant by the term ‘British’ – or at any rate ‘English’. This is the country delegates sing about at the party conferences, the one depicted in heritage brochures and on biscuit tins, the corner that lives in the sentiments of war poetry, an image at the heart of Britain’s view of itself. But here’s the shock: it no longer exists. Everything in Constable’s picture is a small ghost still haunting the national consciousness. The corn poppy has pretty much gone and so have the workers. The days of children drinking from streams are over too. And the livestock? We will come to that. Let me just say that a number of the farmers I spoke to in the winter of 2000 were poisoning their own fields. The Constable picture fades into a new world of intensive industrial farming and environmental blight.

The Cornfield is said to show the path along which Constable walked from East Bergholt across the River Stour and the fields to his school at Dedham. Last October I made my way to Dedham. It was another wet day, and many of the trucks and lorries splashing up water on the M25 were heading to the coast to join a fuel blockade. On the radio a newscaster described what was happening: ‘The situation for the modern British farmer has probably never been so dire, and a further rise in the price of fuel could kill many of them off.’

Before leaving I had rung a pig farmer, David Barker, whose farm is north of Stowmarket in Suffolk. Barker is 50 years old. His family has been farming pigs in Suffolk for four generations; they have lived and worked on the present farm since 1957. He owns 1250 acres and 110 sows, which he breeds and sells at a finishing weight of 95 kilos. Among his crops are winter wheat, winter-sown barley, grass for seed production, some peas for canning, 120 acres of field beans, 30 acres of spring oats and 100 acres of set-aside.

‘Five years ago I was selling wheat for £125 a ton and now it’s £58.50,’ David Barker said. ‘I was selling pigs for £90 and now they’re down to £65. And meanwhile all our costs have doubled: fuel, stock, fertiliser. There’s hardly a farmer in East Anglia who’s making a profit. The direct payments from Europe have declined also because they’re paid out in euros.’

‘What about swine fever?’ I asked, innocent of the epidemics to come.

‘There are over five hundred farms that haven’t been able to move pigs since August,’ he said. ‘Immediately, this becomes an agricultural nightmare. The pigs are breeding, the feed is extortionate, and you end up relying on things like the Welfare Disposal Scheme, where pigs are removed for next to nothing. Gordon Brown’s bright idea: they give you £50 for a pig that costs £80 to produce.’

‘What can be done?’ The stormy weather was making his phone crackly.

‘Well, this Government has no interest in farming,’ he said. ‘People in the countryside in England feel they are ignored and derided and, frankly, it appears that the Government would be much happier just to import food. This is the worst agricultural crisis in dozens of years. We’re not making any money anywhere. Take milk: the dairy farmer receives seven pence in subsidy for every pint; it takes between ten pence and 12 pence to produce and it costs 39 pence when it arrives at your door. A lot of farmers are giving up and many of those who stay are turning to contract farming – increasing their land, making prairies, to make it pay.’

‘Is that the only way to reduce costs?’

‘Yes, that. Or by going to France.’

David Barker used the word ‘nightmare’ at least a dozen times during my conversation with him. He told me about a friend of his, another Suffolk farmer, who, earlier in the swine fever debacle, had sold his 250 pigs into the disposal scheme, losing £30 on each one. Barker himself was waiting for results of blood tests to see if his pigs had the fever. ‘If it goes on much longer it will ruin me,’ he said.

When I arrived at Nigel Rowe’s farm near Dedham only the weather was Constable-like. Out of his window the fields were bare and flat. ‘European pig meat is cheaper to produce,’ he said, ‘because we have higher standards and higher production costs. As soon as foreign bacon gets cheaper by more than ten pence per kilo the housewife swaps. That is the rule.’

I asked him if he felt British supermarkets had been good at supporting bacon produced in Essex or Suffolk. ‘The supermarkets have been very clever at playing the different farming sectors off against each other,’ he said. ‘The Danish model is very centralised – they are allowed to produce and market something called Danish Bacon. We are very regional over here, very dominated by the tradition of the local butcher. Supermarkets want the same produce to be available in Scotland as you get in Sussex. Only the Dutch and the Danish can do that, and some of these foreign producers are so powerful – the Danish producers of bacon are much bigger than Tesco.’

Nigel has 2000 pigs. But he’s not making money. As well as working the farm he has a part-time job as caretaker at the local community centre. ‘In the 1970s we were all earning a comfortable living,’ he said, ‘and when I was at primary school in the 1960s at least thirty of my schoolmates were connected with farming. Now, in my children’s classes, there are three. I had 120 acres and I had to sell it recently to survive. I also had to sell the farm cottage my mother lived in in order to stay here. That’s what I was working on when you came – a little house for my mother.’

He looked out the window at the flatness beyond. ‘The arithmetic is simple,’ he said. ‘When I started in this game it took five tons of grain to buy the year’s supply of fuel for the tractor. Now it takes 500 tons. What do you think that means if your acreage is the same? The Government seem hellbent on the old green and pleasant land, but they won’t get behind the people who keep it that way.’ Nigel sat in his living-room wearing a rugby shirt and jeans speckled with paint from his mother’s new house. ‘They’re not thinking straight,’ he said. ‘Our product needs to be marketed – branded, with a flag, which is presently not allowed. It’s all wrong. We have to import soya as a protein source for our pigs now because we can’t use other animal meat or bone fat. But this country imports tons of Dutch and Danish meat fed on bone fat.’

As we walked out of the living-room I noticed there were no pictures on any of the walls. We went outside to the pigsties. The rain was pouring down, the mud thick and sloppy on the ground, and one of Nigel’s pigs was burning in an incinerator. As we looked out I asked him what had happened to the land. ‘The subsidies from the Common Agricultural Policy have got out of hand,’ he said, ‘because they are linked to production rather than the environment. Did you know the rivers around here are polluted with fertiliser and crap? We’re seeing a massive degradation of rural life in this country. Bakers and dairies have already gone, onions have gone, sugar-beet is gone, beef is pretty much gone, lambs are going.’

Before we went into the sty he asked me if I was ‘pig-clean’. ‘I’m clean,’ I said, ‘unless the fever can come through the phone.’ Hundreds of healthy-looking pink pigs scuttled around in the hay and the mud. He picked one up. ‘Farming is passed down,’ he said, ‘or it should be. A farm is built up for generation after generation, and when it starts to slip and go – you feel an absolute failure. That’s what you feel.’

We went around the farm and Nigel explained how things work. The notebook was getting very wet so I put it away. ‘You feel a failure,’ he said again, looking into the wind. ‘The other night I was at a meeting: 140 farmers at a union meeting paying tribute to four hill farmers under 45 who’d committed suicide.’ He leaned against the side of the barn. ‘We are no longer an island,’ he said, ‘everything’s a commodity.’

Charles Grey, the leader of the Whig Party, won a snap election in 1831 with a single slogan: ‘The Bill, the whole Bill and nothing but the Bill.’ The Reform Act, which was passed the following year after several reversals and much trouble from the Lords, increased the British electorate by 57 per cent and paved the way for the Poor Law and the Municipal Corporations Act; this in turn killed off the oligarchies which had traditionally dominated local government. The misery and squalor that Cobbett had described in the late 1820s worsened during the Hungry Forties; it was not until after the repeal of the Corn Laws, and the subsequent opening up of trade, that British farmers found a brief golden moment. By the end of 1850 Burns and Wordsworth and Constable were dead, and the countryside they adored was subject to four-crop rotation and drainage. Something had ended. And the Census of 1851 shows you what: for the first time in British history the urban population was greater than the rural. Yet the cult of the landscape continues even now as if nothing had changed.

In 1867 it became illegal to employ women and children in gangs providing cheap labour in the fields. This was a small social improvement at a time when things were starting to get difficult again: corn prices fell; there was an outbreak of cattle plague; cheaper produce arrived from America; refrigeration was invented in 1880 and suddenly ships were coming from Australia loaded with mutton and beef. At a meeting in Aylesbury in September 1879, Benjamin Disraeli, by then Earl of Beaconsfield, spoke on ‘The Agricultural Situation’, and expressed concern about British farming’s ability to compete with foreign territories. ‘The strain on the farmers of England has become excessive,’ he said. The year before, he claimed, the Opposition had set ‘the agricultural labourers against the farmers. Now they are attempting to set the farmers against the landlords. It will never do … We will not consent to be devoured singly. Alone we have stood together under many trials, and England has recognised that in the influence of the agricultural interest there is the best security for liberty and law.’ British farming struggled to compete in the open market until 1910, when the Boards of Agriculture and Fisheries and Food were established and the state became fully involved in supporting it. No one was prepared for what was coming next: squadrons of enemy aeroplanes would darken the fields, and out there, beyond the coast, submarines were about to reintroduce the threat of starvation.

Some parts of East Sussex look like Kansas now. For miles all you see is a great rolling carpet of brown or yellow. There are so few trees; sometimes a patch of meadow peeps out, or a factory appears, leading to a giant rustic-style Safeway and a patch of ring-road leading to a town. But mostly you see the featureless prairie leading nowhere. At Bradford Farm, outside Uckfield, there are five modern-looking barns and a house islanded in bushes. At the end of the garden a Union Jack flaps in the wind at the top of a pole. And on the day I came, there were many plums rotting on the trees.

Michael Fordham, the farm’s owner, was driving a new JCB in and out of one of the barns, lifting grain into a waiting lorry. The farm where we stood was 290 acres in all. ‘But we run a further 700 acres from here,’ Michael said, climbing down from the JCB. Michael looks well, with his brown, weathered face and battered jeans. The lorry roared away, taking the grain off to be dried and processed for bread. ‘When I was a boy we used to take the stuff off the combine harvester in sacks,’ he said. ‘There were about ten men running around carrying sacks. Now it never touches human hand. You couldn’t find jobs for ten men now.’

Michael has one man: his father Jim. When I asked him to tell me about his family history a glint appeared in Jim’s eye. ‘My grandfather George was born in 1860,’ he said, ‘and he worked as a butcher and a restaurant owner up in London, near St Paul’s. My father was Arch Fordham and he started a farm in Berkshire, but my mother, Elsie, who was born in 1901, her family was called Stevenson, and they had worked a farm in Fletching since 1760.’ All his family were involved in farming one way or another: his older brother, now dead, owned a farm in Hampshire; his younger brother works for an agricultural machinery business in Vancouver Island; his elder sister is married to a farmer and lives five miles away; the other sister had worked for the Milk Marketing Board in Shropshire. ‘She used to work for the RAF,’ he said. ‘I was too young for the war – I did my bit by farming.’ After telling me all this he pointed to an endless field beside us. ‘A V-1 crashed over there,’ he said. ‘I well remember all the dog-fights overhead.’

Later on, at the door of one of the barns, I listened to a conversation between Michael and his father.

Jim: We all used to work together. We had time to have a chat and a laugh.

Michael: You can’t hear each other now. The machines. Your only contact with people who are working for you is by mobile phone.

Jim: It’s hard for young people to come into it now. When I was young there was always the chance of having a farm. Every farm had some beef, a few pigs, a chicken running about. We had green vegetables. We’d kill a pig once a year.

Michael: Now you’ve got to be really established from the beginning.

Jim: It was a day’s work.

Michael: You live as if you’re going to die tomorrow but farm as if you’re going to be farming for ever.

Jim: That’s an old saying, that. An old local saying.

Michael: My eldest son is 17. He was a great help this summer. But I can’t pay him what he can get working at the golf course up the road. With a farm nowadays it’s all about management and making things balance.

Jim: During the war they would take anything.

Michael: We got two inches of rain on Thursday and the wheat we hadn’t yet harvested lost some of its quality.

Jim: You’ve got to work all hours.

Michael: Do you know what the average age of the British farmer is now? Fifty-eight.

Jim: Fifty-eight. I’m 70. I used to work 16 hours a day.

Michael: I wouldn’t want to be a commuter, though. But I suppose people’s aspirations are different. Rain is the bane of my life.

Jim: I thought that was me.

They both have strong Sussex accents and similar faces; they wear the same jeans and identical watches. And the conversation they have, back and forth, is very typical of arable farmers who are doing all right. It is not the banter of pig or cattle farmers, or the absolute depression of those on the hills. The Fordhams of Sussex are hard workers and profit-makers; they have certainly known better times, but they are making do, by acquiring new machinery and renting larger acreages to allow the technology to earn its keep. Under the wintry sun they have grown coldly industrial. They have bowed to an intensive agricultural process that is pounding the countryside and killing other farmers, but they feel there is nothing else for it.

‘We’re not getting sulphur in the rain any more,’ Michael said. ‘A lot of the factories that produced sulphur have gone. Some of these crops like sulphur so I’ll have to plan ahead for that.’ They recently built a new barn at a cost of £60,000. ‘It’s essential now,’ Michael said. ‘People like Tesco want to know where everything is stored. It’s called Product Assurance.’ Inside the barn the grain was piled very high; it smelled of rain. On the other side of the hangar there were bags of fertiliser. As we drank tea in his cottage Michael made a rice pudding and put it in the Aga.

‘The old farmhouse cooking,’ I joked.

‘My wife works,’ he said. ‘You have to pitch in with everything.’

Michael’s father brought his tea over to the table. ‘It was the wartime government that gave us our head,’ he said. ‘They promoted agriculture at any cost. The subsidy thing really started with that. The present trouble has a long history, but the war made us produce and produce.’

I asked Jim if he’d been happy as an English farmer. ‘I’ve had an understanding bank manager,’ he said. ‘But the Government won’t protect English farming. You’ve just got to face it when things are over.’

Just before evening we drove to one of the detached fields that Michael is farming for a bit of extra profit. We stood in a giant expanse of wheat. A few Scots pines in the distance sparred with electricity pylons. As I crouched at the edge of the field, Michael drove down the incline in the biggest machine I have ever seen: a Claas Dominator 218 combine harvester. It mowed further and further away, cutting, separating, collecting, ejecting rubbish out of a pipe at the side. In five minutes the vast field suddenly seemed too small for the great machine. The blades and the wheels trundled on in the soft wind, and I noticed something eerie in the atmosphere. It took me a while to work it out. There were no birds singing.

Nineteen-fourteen was yet another beginning in British farming. John Higgs argues that the war found agriculture singularly unprepared:

The area under crops other than grass had fallen by nearly 4.4 million acres since the 1870s … and the total agricultural area had fallen by half a million acres. When the war began the possible effects of submarine attacks were unknown and there seemed no reason why food should not continue to be imported as before. As a result only the last two of the five harvests were affected by the Food Production Campaign. This came into being early in 1917 with the immediate and urgent task of saving the country from starvation.

This was the start of a British production frenzy, a beginning that would one day propagate an ending. Free trade was cast aside in the interests of survival, and Agricultural Executive Committees were set up in each county to cultivate great swathes of new land, to superintend an increase in production, with guaranteed prices. The Corn Production Act of 1917 promised high prices for wheat and oats for the postwar years and instituted an Agricultural Wages Board to ensure that workers were properly rewarded for gains in productivity. Some farmers objected to having their produce commandeered for the war effort. One of them, C.F. Ryder, wrote a pamphlet entitled The Decay of Farming. A Suffolk farmer of his acquaintance, ‘without being an enthusiast for the war’, was

quite willing to make any sacrifice for England which may be essential, but, as a dealer in all kinds of livestock, he knows the shocking waste and incompetence with which government business has been conducted, and thinks it grossly unjust that, while hundreds of millions have been wasted, on the one hand, there should be, on the other, an attempt to save a few thousands by depriving the agriculturalist of his legitimate profit.

Despite the words of the non-enthusiast, the war had made things temporarily good for farmers. But the high prices of wartime couldn’t be maintained and in 1920 the market collapsed. This was to be the worst slump in British agriculture until the present one. With diminished world markets and too much grain being produced for domestic use, the Corn Production Act was repealed in 1921. British farmers were destitute.

In A Policy for British Agriculture (1939), a treatise for the Left Book Club, the former Minister for Agriculture, Lord Addison, tried to explain the devastation that took place during those years.

Millions of acres of land have passed out of active cultivation and the process is continuing. An increasing extent of good land is reverting to tufts of inferior grass, to brambles and weeds, and often to the reedy growth that betrays water-logging; multitudes of farms are beset with dilapidated buildings, and a great and rapid diminution is taking place in the number of those who find employment upon them … Since the beginning of the present century nearly a quarter of a million workers have quietly drifted from the country to the town. There are, however, some people who do not seem to regard this decay of Agriculture with much dismay. They are so obsessed with the worship of cheapness at any cost that they overlook its obvious concomitants in keeping down the standard of wages and purchasing power, and the spread of desolation over their own countryside. Their eyes only seem to be fixed on overseas trade.

There are those who argue that it was this depression – and the sense of betrayal it engendered in farmers between the wars – that led the Government to make such ambitious promises at the start of World War Two. Addison’s policy, like many agricultural ideas of the time, was based on a notion of vastly increased production as the ultimate goal. ‘Nothing but good,’ he wrote, ‘would follow from the perfectly attainable result of increasing our home food production by at least half as much again … a restored countryside is of first-rate importance.’

It was too early in the 20th century – and it is perhaps too early still, at the beginning of the 21st – to see clearly and unequivocally that the two goals stated by Addison are contradictory. The vast increases in production at the start of World War Two, and the guarantees put in place at that time, set the trend for overproduction and food surpluses – and began the process of destruction that continues to threaten the British countryside. The pursuit of abundance has contributed to the creation of a great, rolling emptiness. But in the era of the ration-book, production was the only answer: no one could have been expected to see the mountains on the other side.

Two years before Addison took office Thomas Hardy died, and voices were raised in Westminster Abbey, invoking his own invocation of the Wessex countryside:

Precisely at this transitional point of its nightly roll into darkness the great and particular glory of the Egdon waste began, and nobody could be said to understand the heath who had not been there at such a time. It could best be felt when it could not clearly be seen, its complete effect lying in this and the succeeding hours before the next dawn.

It was in Addison’s time that glinting combine harvesters began to appear in the fields.

You hear the Borderway Mart before you see it. Driving out of Carlisle, beyond the roundabouts and small industrial units, you can hear cattle lowing and dragging their chains, and in the car-park there are trucks full of bleating sheep arriving at a market that doesn’t especially want them. Inside you can’t breathe for the smell of dung: farmers move around shuffling papers, eating rolls and sausages, drinking coffee from Styrofoam cups. Some of them check advertising boards covered with details of machinery for sale, farm buildings for rent – the day to day evidence of farmers selling up. ‘It could be any of us selling our tractor up there,’ an old man in a tweed cap muttered at me.

The tannoy crackled into life. ‘The sale of five cattle is starting right now in ring number one,’ the voice said. A black heifer was padding around the ring, its hoofs slipping in sawdust and shit, and the man in charge of the gate, whose overalls were similarly caked, regularly patted it on the rump to keep it moving. Farmers in wellington boots and green waxed jackets hung their arms over the bars taking notes. One or two looked more like City businessmen. The heifer was 19 months old and weighed 430 kg. The bidding was quick and decisive: the heifer went for 79 pence a kilo.

‘If you were here in the prime beef ring six or seven years ago,’ the auctioneer said later, ‘you would have seen the farmers getting about 120 pence per kilo. That is why so many of the farmers are going out of business. Four years ago, young female sheep would be going for eighty-odd pounds, and today they are averaging thirty.’

Back in his office the auctioneer took out his book covering the last few years. ‘Last week, bulls were averaging 82.7 pence per kilo. Three years ago …’ He riffled through the pages. ‘Three years ago the average for bulls was 101.5 pence, and in October 1995, before BSE, the same bulls were fetching 134.2 pence. Think about that. There it is. Black and white. You can’t argue with those figures. Hellish.’ Because of government regulations stemming from the BSE crisis, every cow in Britain now has a passport, which tells where and when it was born, and where it has been since. But despite the seriousness of the attempt to tackle BSE, and the relative healthiness (by EU standards) of the meat on sale here, no one abroad wants British beef any more. People are always sensitive about meat, and they find it difficult to forget bad news – a fact which is already turning the BSE, swine fever and foot and mouth crises into a full-blown catastophe, especially in respect of European buyers.

At the moment there are only two abattoirs that export beef. The market is dead. (Before 1996 British beef was generally considered the best in Europe.) Current EU proposals seem set to tackle overproduction by making subsidy payments relate to acreage rather than headcount. ‘It will result in a reduction in livestock units,’ the auctioneer said, ‘and if we don’t have the units it’s hopeless for the whole community.’ The auctioneer was defending his own business, as he should, but why should taxpayers pay subsidies to farmers?

The auctioneer’s boss is more strident. ‘The industry’s going under,’ he says, ‘and you’ll notice something: the Common Agricultural Policy works for the rest of the European Union but it’s not working for us.’

‘In what ways?’ I asked.

‘Well, first, the animal welfare rules are more strongly applied here than anywhere, and in this, as in so many areas, British farmers find themselves not to be on a level playing field. We are not competing on equal ground. The weakness of the euro, with the subsidy payments coming in euros, is a killer;4 and as well as that we are still being punished over the BSE crisis. There doesn’t seem to be the appreciation in some quarters …’

‘You mean Government?’

‘I’m not going to say that … Confidence has dropped. This is the largest mart in the UK, and what we see is that volumes are holding up, but costs have gone out of control: increased animal welfare, water usage, effluent handling and passports. Today alone we will be handling 1500 passports for cattle.’

The boss dropped his middle finger ominously onto the table. ‘Unless there is reinvestment the industry will … well, you check your crystal ball,’ he said. ‘It is unbelievably serious in the rural community and I don’t think people properly appreciate it. It’s no longer a North/South divide we have in this country: it’s a rural/urban divide. It’s easy to work out: after eighteen months or more of breeding and feeding and labour, a farmer today is walking home with £339.70 for a good heifer. Nothing.’ Five months after he said this, many of the farmers weren’t even getting that. ‘Nothing’ was the accurate figure; compensation the only hope.

Climbing to Rakefoot Farm outside Keswick, you see nothing but hills and, in the distance, the lakes like patches of silver; tea shops and heritage centres and Wordsworth’s Walks serve as punctuation on the hills going brown in the afternoon. Will Cockbain was sitting in front of a black range in a cottage built in 1504. ‘There are ghosts here,’ he said, ‘but they’re mostly quite friendly.’

Will’s father bought Rakefoot Farm in 1958, but his family has been working the land around Keswick for hundreds of years. ‘There are more Cockbains in the local cemetery than anything else,’ he said, ‘and they have always been sheep farmers. Sitting here with you now, I can remember the smell of bread coming from that range, years ago, when my grandmother was here.’ Will has 1100 Swaledale sheep and 35 suckler cows on the farm. ‘Seven thousand pounds is a figure you often hear as an annual earning for full-time farmers round here,’ he said. ‘Quite a few are on Family Credit – though not many will admit it. We farm 2500 acres, of which we now own just 170, the rest being rented from five different landlords, including the National Trust. The bigger part of our income comes from subsidies we get for environmental work – keeping the stone walls and fences in order, maintaining stock-proof dykes, burning heather, off-wintering trees.’

‘Can’t you make anything from the sheep?’ I asked.

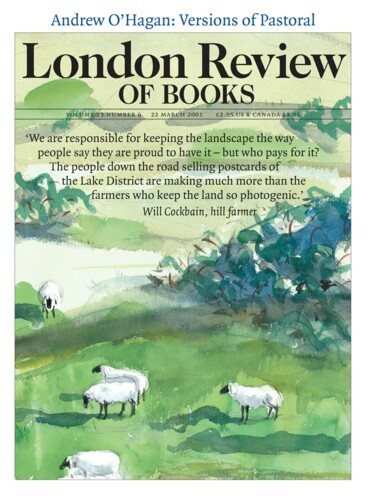

‘No,’ he said. ‘We are selling livestock way below the cost of production. Subsidies were introduced in 1947 when there was rationing and food shortages, and the subsidies continued, along with guaranteed prices, and now even the subsidies aren’t enough. We’ve got the lowest ewe premium price we’ve had for years. In hill farming the income is stuck and the environmental grants are stuck too. Fuel prices are crippling us. We are in a job that doesn’t pay well and we depend on our vehicles. We are responsible for keeping the landscape the way people say they are proud to have it – but who pays for it? The people down the road selling postcards of the Lake District are making much more than the farmers who keep the land so photogenic.’

Will Cockbain was the same size as the chair he was sitting in. Staring into the fire, he waggled his stocking-soled feet, and blew out his lips. ‘I think Margaret Thatcher saw those guaranteed prices farmers were getting and just hated it,’ he said, ‘and now, though it kills me, we may have to face something: there are too many sheep in the economy. Farmers go down to the market every other week and sell one sheep, and then they give thirty or forty away. They’re not worth anything. There are mass sheep graves everywhere now in the United Kingdom.’ Will laughed and drank his tea. ‘It’s only those with an inbuilt capacity for pain that can stand the farming life nowadays,’ he said. ‘I like the life, but you can’t keep liking it when you’re running against the bank, when things are getting out of control in ways you never dreamed of, relationships falling apart, everything.’

On the walls of Will Cockbain’s farm there are dozens of rosettes for prize-winning sheep. A picture of Will’s son holding a prize ram hangs beside a grandfather clock made by Simpson of Cockermouth, and an old barometer pointing to Rain. ‘This is a farming community from way back,’ Will said, ‘but they’re all getting too old now. Young men with trained dogs are a rarity, and hill farming, of all kinds, needs young legs. We’ve lost a whole generation to farming. My boys are hanging in there for now, but with, what, £27,000 last year between four men, who could blame them for disappearing?’

Another day, in the tiny kitchen of a hill farm above Bewcastle, eight hundred feet above sea level, a little girl called Louise Carruthers walks to the sink in her blue parka, carrying a jug of water. She smiles and looks like a girl in a Vermeer. ‘I’ve made nothing this year,’ her father, Brian, tells me. ‘I’m on Family Credit and dependent on Family Allowance to get from week to week. And I’m working from daylight to dark. I’m trying to encourage my boy not to go into this. One of my friends gave up and now he’s working on a building site earning £280 a week.’

Brian’s farm is a confusion of mist and rotting leaves. When I arrived he slammed the door of his Land-Rover shut and tasted the air. ‘Last year we were buying fuel at 11 pence a litre, and now it’s 22 pence, and has even been up as high recently as 27 pence.’ Inside the cottage, there is a pair of Massey Ferguson overalls hanging above the Aga and a waxcloth on the table. ‘You know all the reasons for this,’ he said, ‘but people ought to look at the supermarkets: they are really taking the piss. They talk about partnerships and all that but they have the farmers at each other’s throats. Forget the landscape, forget the culture, and forget traditions, forget the efforts being made by farmers to produce good quality stuff – most supermarkets will buy from wherever they get the best deal. They don’t support the British farmer, although it suits them to say they do. They squeeze everyone.’

Couldn’t Brian diversify? ‘Oh aye,’ he said, ‘they’re always talking about diversify. Into what? It’s hard to believe the way people plough nowadays. You can’t buy into that now, not with those giant agribusiness people, who buy everything and turn it arable. Tenant farmers are no match for those big businesses. Diversify? How else? It’s heavy clay land up here, it’s wet, there’s no tourism, no ponies, no golf.’

‘So what do farmers do who can’t cope?’ I asked.

‘Commit suicide,’ he said, ‘or drive a dumper.’5

Brian is 42 years old. He is separated with two children. His wife left him after beginning an affair with a man she met in the office where she worked. He keeps all his cattle passports in a tin and at one point he held a passport up and said to Louise: ‘It looks a bit like our Family Allowance book.’ They’d been watching Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? the previous night, ‘and this guy lost £125,000 on a question we knew the answer to. It was amazing, wasn’t it, Louise?’

Out in the yard I saw some of Brian’s Galloway cows. It takes three years for these famous cows to mature but under the new BSE regulations cows have to be slaughtered before their 30th month. Brian patted one of the cows on the way past. ‘It’s going to be a nightmare if they let farming go the same way as mining,’ he said, ‘but still, we all vote Conservative up here. The Tories were much better to us.’

You could see the Solway Firth twenty miles away. There it was: Scotland and England balanced along a line of blue mist. And it felt as if there was a freeze coming down. Brian nudged me with his arm as I left, and he laughed, looking into the wild unpeopled hills. ‘If you find me a new wife make sure she’s an accountant,’ he said.

As early as 1935 there was panic in the Ministry of Agriculture about the possibility of another war. The First World War had caught British agriculturalists on the hop: this time preparations had to be made. And it was this panic and this mindfulness that set in train the subsidy-driven production that many feel has ruined (and saved) the traditional farming economy in this country, creating an ‘unreal market’ and a falsely sustained industry, the root of today’s troubles. Before the outbreak of war, policies were introduced which favoured the stockpiling of tractors and fertilisers; there were subsidies for anyone who ploughed up permanent grasslands; agricultural workers were released from war duty; and the Women’s Land Army was established. Farming became the Second Front, and the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign extended from public parks to private allotments.

With the war at sea British food imports dropped by half while the total area of domestic crops increased by 63 per cent: production of some vegetables, such as potatoes, doubled. Farmers in the 1930s had complained that their efforts to increase production in wartime had not been rewarded by an undertaking of long-term government support. The mistake would not be repeated. Promises were made at the start of the war, and in 1947, with food shortages still in evidence and rationing in place, an Agriculture Act was passed which offered stability and annual price reviews to be monitored by the National Farmers’ Union. Parliament instituted a massive programme of capital investment in farm fabric and equipment, and free advice on the use of new technologies and fertiliser was made available. Water supplies and telephone lines were introduced in many previously remote areas. Farmers working the land in the 1950s and 1960s, though there were fewer and fewer of them, had, it’s true, never had it so good. At the same time increased use of artific-ial fertilisers and chemical pesticides meant greater yields and what is now thought of as severe environmental damage: motorway bypasses, electricity pylons, larger fields attended by larger machines, with meadows ploughed up, marshes filled in, woods and grasslands usurped by acreage-hungry crops – what the writer Graham Harvey refers to as ‘this once “living tapestry”’ was being turned into ‘a shroud … a landscape of the dead’.6

Government subsidies and grants in wartime, cemented in postwar policy, prepared British farmers for the lavish benefits they were to enjoy after Britain joined the Common Market in 1973. Today, the Common Agricultural Policy gets a lashing whatever your view of the EU. One side sees quotas and subsidies and guaranteed prices as responsible for overproduction and the creation of a false economy. The other accuses it of being kinder to other European states and not giving enough back to British farmers, a view generally shared by the farmers themselves, but secretly abhorred by the Government, which is handing out subsidies. The two sides agree, however, that the CAP doesn’t work, and as I write a new round of reforms is being introduced.

In 1957, when the Common Market came into being, there was a deficit in most agricultural products and considerable variance in priorities from state to state – some to do with climate and dietary needs, some to do with protectionist tendencies. (British farmers who feel ill-served by the CAP often say it was formed too early to suit British needs.) The CAP came into effect in 1964. It was intended to rationalise the chains of supply and demand across member states. This was to be achieved by improving agricultural productivity and promoting technical progress; by maintaining a stable supply of food at regular and sensible prices to consumers; by setting up a common pricing system that would allow farmers in all countries to receive the same returns, fixed above the world market level, for their output. Agricultural Commissioners were given the right to intervene in the market where necessary, and a system of variable levies was established to prevent imported goods undercutting EC production. The vexed issue was the common financing system, which still operates today, and which means that all countries contribute to a central market support fund called the European Agricultural Guidance and Guarantee Fund, or EAGGF. All market support is paid for centrally out of this fund, with budgetary allocations for each commodity sector. Cash is paid out to producers in member states regardless of the level of a country’s contribution to the fund.

One consequence of this protectionist jamboree has been an increase, across the board and in all member states, in the variety and quality of available products, from plum tomatoes and cereals to hams and wines and cheeses, with modern supermarkets now carrying a vastly increased range of produce at comparable prices. (This may have pleased British consumers but it hasn’t pleased British farmers, who argue that supermarkets have exploited this abundance, breaking traditional commitments to local producers, and ‘shopping around Europe’ for supplies which could be got in Britain.) A second consequence has been the familiar overstimulated production and the creation of surpluses. It may even be that by continuing to offer not only guaranteed prices but production subsidies to boot, the CAP can be considered one of the chief instigators of the current crisis.

In the early 1990s, European agriculturalists, seeing the need for the CAP to give direct support to an ailing industry – ‘to protect the family farm’, as they often put it – and to save the environment, began to speak a different language. The European Commission, in its own words,

recognised that radical reforms were necessary in order to redress the problems of ever-increasing expenditure and declining farm incomes, the build up and cost of storing surplus food stocks and damage to the environment caused by intensive farming methods. A further factor was the tensions which the Community’s farm support policy caused in terms of the EC’s external trade relations. Various measures have been adopted since the mid-1980s to address these problems, e.g. set-aside, production and expenditure quotas on certain products and co-responsibility levies on others. However, these proved inadequate to control the expansion of support expenditure.

A constant refrain during the Thatcher period was that measures like these would only serve to impede market forces. The bucking of market forces, however, was one of the founding principles of the CAP, and even today, when we finally see the bottom falling out of the system of rewards and grants for overproduction, the tendency is towards ‘relief’ packages, which New Labour support through gritted teeth. It would appear that for a long time now British farming has been faced with two choices: a slow death or a quick one. And not even Thatcher could tolerate a quick one.

The first round of CAP reforms, in December 1993, had three main results: better prices for consumers, a scaling down of production and concomitant reduction in surpluses, and greater attention to matters of environmental concern. The benefit to British farmers took the usual form: subsidies. Burning heather and building fences brings in a few extra euros. But the cost to the state remains unbelievably high: of just over £600 million in aggregate farming income in Scotland in 1995, £400 million came in financial aid.

The EU’s Agenda 2000 set out further CAP changes for the new millennium, made necessary in part by the potential eastward expansion of the Union (‘major income differences and other social distortions’ would arise, and surpluses would grow even larger). The Commission proposed to cut the beef price guarantee by 30 per cent between 2000 and 2002, and to compensate any loss of income with direct payments; member states would be given a degree of independence in deciding how the money was spent. A similar approach was put forward for the dairy sector: the present quota system will remain in place until 2006, by which time average support prices are to be cut by 10 per cent; this will be offset by a yearly payment for dairy cows. A 20 per cent cut in the cereals intervention price in 2000, accompanied by flat-rate partial compensation for arable crops and the abolition of compulsory set-aside, is meant to prevent a heavy potential increase in cereals surpluses, which could reach 58 million tons by 2005. There is to be greater emphasis on ‘a more environmentally sensitive agriculture’. Subsidies higher than 100,000 euros per farm are to be capped.

Consumers stand to save more than a billion pounds from the cuts in support prices; and the Blair Government is largely in agreement with these proposals, although there are elements which, according to documents available from the Scottish Executive,7 it finds less than satisfactory:

While the general proposals for addressing rural policy lack detail, they look innovative and offer possibilities for directing support to rural areas. The downside of the proposals is that the compensation payments look to be too generous, there is no proposal to make farm payments degressive or decoupled from production . . . The Government has also declared its opposition to an EU-wide ceiling on the amount of direct payments which an individual producer can receive. Because of the UK’s large average farm size, this proposal would hit the UK disproportionately. Elsewhere, there is uncertainty about how the proposals would work in practice. This includes the proposal to create ‘national envelopes’ in the beef and dairy regimes within which Member States would have a certain discretion on targeting subsidies.

A modern journey across rural Britain doesn’t begin and end with the Common Agricultural Policy. Since the end of the Second World War, and escalating through the period since the formation of the EEC, what we understand as the traditional British landscape has been vanishing before our eyes. Something like 150,000 miles of hedgerow have been lost since subsidies began. Since the underwriting of food production regardless of demand, 97 per cent of English meadowlands have disappeared. There has been a loss of ponds, wetlands, bogs, scrub, flora and fauna – never a dragonfly to be seen, the number of tree sparrows reduced by 89 per cent, of song thrushes by 73 per cent and of skylarks by 58 per cent. ‘Only 20 acres of limestone meadow remain in the whole of Northamptonshire,’ Graham Harvey reports. ‘In Ayrshire only 0.001 per cent remains in meadowland . . . None of this would have happened without subsidies. Without taxpayers, farm prices would have slipped as production exceeded market demand . . . Despite years of overproduction, farmers continue to be paid as if their products were in short supply.’

I set out on my own rural ride feeling sorry for the farmers. I thought they were getting a raw deal: economic forces were against them, they were victims of historical realities beyond their control, and of some horrendous bad luck. They seemed to me, as the miners had once seemed, to be trying to hold onto something worth having, a decent working life, an earning, a rich British culture, and I went into their kitchens with a sense of sorrow. And that is still the case: there is no pleasure to be had from watching farmers work from six until six in all weathers for nothing more rewarding than Income Support. You couldn’t not feel for them. But as the months passed I could also see the sense in the opposing argument: many of the bigger farmers had exploited the subsidy system, they had done well with bumper cheques from Brussels in the 1980s, they had destroyed the land to get the cheques, and they had done nothing to fend off ruin. When I told people I was spending time with farmers, they’d say: how can you stand it, they just complain all day, and they’ve always got their hand out. I didn’t want to believe that, and, after talking to the farmers I’ve written about here, I still don’t believe it. But there would be no point in opting for an easy lament on the farmers’ behalf, despite all the anguish they have recently suffered: it would be like singing a sad song for the 1980s men-in-red-braces, who had a similar love of Thatcher, and who did well then, but who are now reaping the rewards of bad management. As a piece of human business, British farming is a heady mixture of the terrible and the inevitable, the hopeless and the culpable, and no less grave for all that.

Britain is not a peasant culture. It has not been that for over two hundred years. Though we have a cultural resistance to the fact, we are an industrial nation – or, better, a post-industrial one – and part of the agricultural horror we now face has its origins in the readiness with which we industrialised the farming process. We did the thing that peasant nations such as France did not do: we turned the landscape into a prairie, trounced our own ecosystem, and with public money too, and turned some of the biggest farms in Europe into giant, fertiliser-gobbling, pesticide-spraying, manufactured-seed-using monocultures geared only for massive profits and the accrual of EU subsidies. A Civil Service source reminded me that even the BSE crisis has a connection to intensive agribusiness: ‘feeding animals with the crushed fat and spinal cord of other animals is a form of cheap, industrial, cost-effective management,’ he said, ‘and it would never have happened on a traditional British farm. It is part of the newer, EU-driven, ultra-profiteering way of farming. And look at the results.’8 Farms in other parts of Europe, the smaller ones dotted across the Continent, have been much less inclined to debase farming practices in order to reap the rewards of intensification.

The way ahead is ominous. In a very straightforward sense, in the world at large, GM crops are corrupting the relation of people to the land they live on. Farmers were once concerned with the protection of the broad biodiversity of their fields, but the new methods, especially GM, put land-use and food production into the hands of corporations, who are absent from the scene and environmentally careless. By claiming exclusive intellectual property rights to plant breeding, the giant seed companies are gutting entire ecosystems for straight profit. In Brave New Seeds: The Threat of GM Crops to Farmers, Robert Ali Brac de la Perriere and Franck Seuret investigate the hidden effects of GM-promoted intensification.9 ‘Today,’ they write,

the biotechnological giant Monsanto and others claim a monopoly on plant breeding, not directly but through patents and transgenic seeds. They sell very expensive seeds which require heavy agricultural inputs. Worse, the farmer has no right to reuse them for further sowing or cross-breeding . . . It is the genetic revolution that may engender a new way of intensified agriculture and the programmed elimination of small farmers.

It is happening in India, Algeria, and increasingly in places like Zimbabwe,10 and it is among the factors threatening to make life hell for the traditional farmers of Yorkshire and Wiltshire.

In 1998, in a leaked document, a Monsanto researcher expressed great concern about the unpopularity of GM foods with the British public, but was pleased to report that some headway had been made in convincing MPs of their potential benefits. MPs and civil servants, the document says, have little doubt that over the long term things will work out, with a typical comment being: ‘I’m sure in five years’ time everybody will be happily eating genetically modified apples, plums, peaches and peas.’

In 1999 the Blair Government spent £52 million on developing GM crops and £13 million on improving the profile of the Biotech industry. In the same year it spent only £1.7 million on promoting organic farming. Blair himself has careered from one end of the debate to the other, swithering between his love of big business and his fear of the Daily Mail. Initially, he was in favour of GM research in all its forms: ‘The human genome is now freely available on the Internet,’ he said to the European Bioscience Conference in 2000, ‘but the entrepreneurial incentive provided by the patenting system has been preserved.’ Other voices – grand ones – disagreed. ‘We should not be meddling with the building blocks of life in this way,’ Prince Charles was quoted on his website as saying.11 The Government asked for the remarks to be removed. ‘Once the GM genie is out of the bottle,’ Sir William Asscher, the chairman of the BMA’s Board of Science and Education remarked, ‘the impact on the environment is likely to be irreversible.’ The Church of England’s Ethical Investment Advisory Group turned down a request from the Ministry of Agriculture to lease some of the Church’s land – it owns 125,000 acres – for GM testing. More recently, Blair has proclaimed in the Independent on Sunday that the potential benefits of GM technology are considerable, but he has also introduced the idea that his Government is not a blind and unquestioning supporter. ‘We are neither for nor against,’ said Mo Mowlam.

Poorly paid, unsung, depressed husbanders of the British landscape, keeping a few animals for auld lang syne, and killing the ones they can’t afford to sell, small farmers like Brian Carruthers, the man who lives outside Keswick with his Galloway cows and keeps his children on Family Credit, or the pig farmers in Suffolk, told me they felt as if they were under sentence of death from the big agricultural businesses. I asked one of them what he planned to do. His response was one I had heard before. ‘Move to France,’ he said, with a shrug. Graham Harvey is in no doubt about where the fault lies: ‘In the early 1950s,’ he writes, ‘there were about 454,000 farms in the UK. Now there are half that number, and of these just 23,000 produce half of all the food we grow. In a period of unprecedented public support for agriculture almost a quarter of a million farms have gone out of business . . . It is the manufacturers and City investors who now dictate the UK diet.’

The Government has been stuck in farming crisis after farming crisis, but it recognises – though until now somewhat mutedly – the accumulating evils of the subsidy-driven culture. In a White Paper introduced in Parliament at the end of last year,12 the New Labour view of agricultural progress was clarified:

Subsidies which simply reward production have damaged the countryside and stifled innovation. A complicated bureaucracy has created expensive surpluses of basic products and has prevented farmers from responding to what customers really want. The CAP must be further deregulated so that agricultural production can adapt to a competitive world market. Production quotas which prevent farmers from responding to the market must be removed . . . In a few years we will have an expanded EU with up to 12 more member states and a total population of 500 million people. Without CAP reform, the budgetary consequences would be unsustainable. Negotiations have also begun on liberalising agricultural trade in the World Trade Organisation. This will open up new markets as well as exposing us to greater competition . . . The Government recently secured EU approval for the England Rural Development Programme, which includes a major switch of CAP funds from production aids to support for the broader rural economy. We will spend £1.6 billion by 2006 – around 10 per cent of total support for the agriculture industry – on measures to advance environmentally beneficial farming practices as well as on new measures to develop and promote rural enterprise and diversification, and better training and marketing.

This is the Government’s public position: large-scale, environmentally-friendly tinkering with European funding, attended by vague worries about changes in the world market. An unofficial spokeswoman for Maff told me there were much deeper worries than the policy-wonks would be heard admitting to. ‘It is like the end of the British coal industry,’ she said:

but no one wants to be Ian McGregor. In the time since BSE 110,000 head of cattle have disappeared: it seems that farmers were burning them on their own land. It’s a cultural thing, too: no one wants to admit that a certain kind of farming, a certain way of English life, has now run to the end of the road. People will supposedly always need bread. But there is no reason to believe it will have to be made with British ingredients. The disasters in farming aren’t so temporary. And they aren’t mainly the result of bad luck. No. Something is finished for traditional farming in this country. Not everything, by any means, but something – something in the business of British agriculture is over for good, and no one can quite face it.

The day before I set off for Devon there was a not entirely encouraging headline on the front of the London Evening Standard: ‘Stay Out of the Countryside’. Just when it seemed there was little room for disimprovement in the predicament of British farmers, news came of the biggest outbreak of foot and mouth disease in more than thirty years. Twenty-seven infected pigs were found at Cheale Meats, an abattoir in Essex, a place not far from Nigel Rowe’s pig farm in Constable country. Infected animals were quickly discovered on several other farms. Suspicious livestock began to be slaughtered in their hundreds. Such was the smoke from the incineration site in Northumberland that the A69 had to be closed for a time. British exports of meat and livestock (annual export value £600 million) as well as milk (of which 400,000 tons are exported a year) were banned by the British Government and the EU. ‘It is like staring into the abyss,’ Ben Gill, the President of the National Farmers’ Union, said. ‘On top of the problems we have had to face in the last few years, the impact is unthinkable.’