10 June 1993. Fellow-guests with Tony and Cherie Blair at a BBC dinner. Blair says immediately to my wife: ‘Weren’t you kind enough to ask me to a drinks party for Frank Field’s 50th birthday?’ She answers: ‘Yes, and you neither came nor replied.’ ‘Didn’t I?’ says Blair, and subsequently sends a charming letter of apology. The thought that this smiling young Scottish public schoolboy could be the next prime minister doesn’t cross either of our minds. On the other hand, John Birt is suitably impressed when I tell him that I actually met the great Lord Reith on the day of his extraordinary speech in the House of Lords likening commercial broadcasting to the Black Death. It was as if I’d said to the present Chief of the Defence Staff that I’d met the first Duke of Wellington.

15 March 1994. A reply arrives from John Major to a letter I’d written to him trying to persuade him to reform the House of Lords. It begins with ‘I have to confess that this is not an issue which I am strongly minded to open up at this stage,’ and ends with ‘may I reiterate’ thanks to me for chairing the 1991-93 Royal Commission on Criminal Justice (which is, I suppose, all the nicer since in fact it’s the first thanks I’ve had from him). He tells me to go and talk to John Wakeham, which I do. Wakeham is as cynical as he is agreeable, saying that I’m one of many who’ve said the same to him, but it isn’t on for three reasons: first, a lame-duck government couldn’t get a constitutional Bill through the Commons; second, they need the backwoodsmen to get their current legislation passed without hassle; third, the punters don’t give a toss. Suggests I write to the Times, to which I reply that I wrote to the Prime Minister precisely because I know that a letter to the Times from me or anybody else would have absolutely no effect, but I thought reform of the Lords might be better achieved by his party.

28 April 1996. Derry and Alison Irvine are fellow guests at a dinner party at the Dworkins. The collective rate of encroachment on our hosts’ wine supply is truly awesome. I am reminded of Winston Churchill saying to my father about his – my father’s – teetotal father, who had been a colleague of Churchill’s in Asquith’s Cabinet: ‘I have often thought that your father would have been a happier man if he had taken an occasional glass of whisky, as I do.’ Derry is ebulliently confident of soon tasting the fruits of high office.

27 March 1997. Seated next to John Prescott at lunch at the Chamber of Shipping. Am careful not to mention the last occasion, which I’m sure he has forgotten, in (I think) 1985, when he came to a similar lunch in the House of Commons, addressed not a word to me after the initial handshake, launched into a diatribe about P&O replacing Brits with foreigners in the catering department of one of their cruise ships, and then left before the P&O representative at the lunch was able to explain that all the proper procedures including a shipboard ballot had been followed. On this occasion, Prescott plays the working class patriot and statesman in the Bevin mould and does it rather well – exuding an expansive sense of power being within reach at last.

1 May 1997. Run into John Eatwell, formerly economic adviser to the hapless Neil Kinnock and now Lord Eatwell, President of Queen’s, at Cambridge station. We naively agree that it can’t possibly be a landslide, given the percentage of the British electorate which will vote Conservative no matter what the level of arrogance, disunity and sleaze. When first disenfranchised, I was rather glad not to have a vote, since although wanting Thatcher out I didn’t at all want Kinnock in. But this time I am sorry not to have a vote to cast for Blair, however little he turns out to need it

5 May 1997. Frank Field describes being rung up from Downing Street in the aftermath of the election to be asked to take the job of Minister for Welfare Reform outside the Cabinet, to serve under Harriet Harman as Secretary of State. Frank is surely right to accept on that basis, even though he’s by now forgotten more about the details of the system than Harriet will ever learn, rather than consign himself to the back benches at the very beginning of a government whose attitude to welfare reform he has already done so much to change. Harriet, as it happens, used to be a baby-sitter for us, when her parents lived next door to us in St John’s Wood. As we say in writing to congratulate her, when one’s baby-sitter is a cabinet minister one realises one is really old!

21 May 1997. Howard Davies is appointed chairman-designate of ‘SuperSIB’ (or, as it is later christened by Gordon Brown, the Financial Services Authority), as much to his surprise as everyone else’s. He had been on his way to South America in his capacity as deputy governor of the Bank of England, having just been involved in that same capacity in seeking a successor to Andrew Large as chairman of SIB in its existing form, when Brown rang him up and put it to him. All very good news, both because we (the SIB board) had been trying without success to persuade the last government to give legislative time to reform the manifestly inadequate Financial Services Act of 1986 and because if all financial regulation, including banking supervision, is to be wrapped up inside a single SuperSIB, Howard is unquestionably the right person to head it. But why does Brown not disown the anonymous spinner who told the newspapers that the Governor of the Bank was ‘playing into our hands’ by letting it be known that he didn’t think he’d been adequately consulted about the transfer of banking supervision? Can it be that he intends to appoint one of his acolytes to be governor instead of giving ‘Steady Eddie’ George a further term and letting the markets know it sooner rather than later?

15 July 1997. To St Paul’s for the memorial service for Lord Chief Justice Peter Taylor. The first and best address is given by Humphrey Potts, a lifelong friend of Peter’s from their time together at the Royal Grammar School in Newcastle and now himself Hon. Mr Justice Potts of the Queen’s Bench Division. It’s not long after Derry Irvine has made a speech denouncing ‘fat cat’ barristers and Humphrey, having firmly stated that Peter was never one of these, goes on, after a pause which makes everyone sit up, to refer to remarks made by a Lord Chancellor suffering from ‘post-practice remorse’. Afterwards, Humphrey tells us that it only occurred to him on the way to the service, and the pause was due not to histrionic skill but to a sudden panic that he might commit a Freudian lapse into ‘post-coital’ remorse.

17 July 1997. Annual visit of the SIB board to the Chancellor of the Exchequer. Gordon Brown as genial and forthright in his way as Kenneth Clarke had been last year in his. First sight of lightly-bearded Alistair Darling, who strikes me as if chosen from a thousand aspirants to be cast as Iago at Covent Garden: is it, I wonder, an advantage in political life to look quite so operatically handsome, but sinister? Brown takes me aback by talking to me not about financial regulation but about having been assigned to read my book Relative Deprivation and Social Justice when he was an undergraduate. What, he asks, am I writing now? I tell him I have just published a long-gestated volume about the sociology of 20th-century England. What I don’t tell him is that it systematically devalues the importance of political decision-makers in the explanation of what actually makes a society the kind of society it is.

17 September 1997. To 10 Downing Street to see Pat McFadden of the Prime Minister’s Policy Unit about House of Lords reform. As I sit quietly in the entrance hall, there suddenly irrupt, stride past, and disappear through the front door Major Ashdown and his little platoon of MPs – shoulders squared, eyes front, chins thrust forward, as if on their way to a Royal Marine assault course. Next appears Robin Cook, who is led aside by Alastair Campbell and rehearsed in conspiratorial whispers about what he is to say to the reptiles waiting across the road. Cook, whom I’ve never met, gives me a quick, suspicious look. Alastair, whom I have, carefully ignores me. The Supremo of Spin moves over to the window, looks across, signals; the front door is again opened, the Foreign Secretary emerges on cue, the cameras flash, the door closes behind him. I reflect that it’s more like a stage set than a stage set. Pat duly appears and leads me off to an enormous drawing-room, where we sit on huge facing sofas in echoing splendour. I suggest, without mentioning names, that one or two of the fairly recently ennobled might not have got past a seriously worldly and well-informed scrutiny committee: why can’t we have a proper system of selection for merit instead of a choice between heredity, political patronage and partisan electoral contests between status-seeking wannabes? Pat suggests that I put my thoughts in writing to Derry Irvine, which I subsequently do. A polite letter comes back from Derry thanking me for my trouble and proposing that we have a chat when he’s a little less hard-pressed; I know he knows I know that no such chat will take place. As I leave No. 10, one tiny flashbulb pops as if there was a faint chance that I might be an important person.

4 October 1997. Dinner at the country house of the Baroness Dunn. Henry (‘Taipan’) Keswick and the now ex-ministerial but ever-amusing Richard Needham are fellow-guests. A heated disagreement between them about Chris Patten’s governorship of Hong Kong flares up and amicably subsides. Entirely by chance, we meet the Pattens in London the very next evening for the first time since long before they went to Hong Kong. Impossible to resist mentioning the Keswick/Needham confrontation, by which Patten is totally unsurprised. Much curiosity about what he sees himself doing next, but no clues are given. If he hadn’t lost his seat the time before last, might his finger in the dike have held back the flood of arrogance, disunity and sleaze by which Major was overwhelmed?

21 October 1997. Coopers & Lybrand dinner for selected corporate clients at the Lanesborough Hotel. I am placed next to Ed Straw, Jack’s brother, whom I immediately take to. He tells me the family history and assures me that in student days he was far to the left of Jack, whom he regarded as hopelessly bourgeois. I wonder what hefty six-figure income Ed now takes home annually as a C&L partner auditing big hightech PLCs, but don’t of course ask.

4 November 1997. To hear Gordon Brown give a lecture under the improbable auspices of the Spectator and Allied Dunbar. We sit near the front with friends and agree to count the number of times Brown uses the words ‘modern’ and ‘modernisation’. We soon give up, but one of our little group carries on to eight. I suddenly realise that our nudges and giggles might be visible from the rostrum. If so, does the Chancellor guess why? Surprisingly frequent invocations of George Orwell in the lecture – not very apt, considering how intensely Orwell would have disliked New Labour. Am reminded of an essay written by the sociologist Philip Abrams back in 1964 in which he complained about ‘the difficulties our political leaders evidently have in saying exactly what they mean when they speak of “modernising” British society’.

5 November 1997. To hear Lord Nolan give the annual Dimbleby Lecture. Heavy turnout of Great and Good. My wife is next to Nolan at the dinner and tells him how time-consuming and expensive Nolanisation has been for the Mental Health Act Commission with its 160 appointed members. Received without comment. She goes on to ask: ‘How did you choose your members?’ Of the first cited, Nolan at once replies: ‘He was in my chambers.’ Good to dine out on, but as somebody fairly points out, Nolan was by definition choosing his members pre-Nolanisation.

12 November 1997. To Quentin Skinner’s inaugural lecture as Regius Professor of History at Cambridge. Any method of appointment would have achieved the same result, but I recall his wry description of being summoned to Downing Street on a busy weekday for a lengthy, courteous, but purely ritual chat with a senior member of the Prime Minister’s patronage office. Not all previous incumbents were as wisely chosen by the prime ministers of their day. I subsequently send Quentin a postcard with the following quotation from a review by the late Richard (‘l’étonnant’) Cobb of English historians of the French Revolution: ‘There must be some consolation for present holders of Regius Chairs and hope for future ones to discover just how bad, how indolent, how wrong-headed and how feeble some of their predecessors have been.’

26 November 1997. To hear Gordon Brown again, this time over a Coopers & Lybrand breakfast at the Savoy. Is it a wish for genuine consultation with the business community, or just spinnery? Geoffrey Robinson presides, prompting reflections about the kind of businessmen who succeed, however improbably, in winning the trust of left-wing politicians. Who exploits who? When it’s David Lloyd George, he exploits them. But when it’s Harold Wilson?

2 December 1997. Unable to attend Peter Hennessy’s public lecture on Blair’s version of prime-ministerial government, but he sends a copy. It confirms the impression that collective cabinet responsibility is as mythological as it was under Margaret Thatcher, but with the difference that Blair allows signal latitude to his two over-mighty chancellors. Am reminded of Peter saying to my wife in the run-up to the election that when he came back from giving seminars to shadow ministers about the machinery of government, he was so depressed by the combination of ignorance and arrogance in some of them that he said to his wife: ‘If I knew what Prozac was, I’d take it!’ How, I wonder, will the historians of the future calculate the damage incidentally done to the quality of government when one party is in power for much too long and the incomers are therefore wholly without previous experience of office?

1 January. Delighted to see a CH for Eric Hobsbawm and a CBE for David Lockwood in the New Year Honours. Would either have been honoured at all without the change of government? David, although Britain’s number one sociologist, is almost the only academic I know who is wholly without the vanity which Max Weber called the besetting sin of all academics: as I once said in reviewing a book of David’s for the LRB, he not only hides his light under a bushel but hides the bushel.

12 January. To hear Ross McKibbin give a talk at the LRB about the ‘Blair Project’ – a phrase which I for one can’t pronounce without embarrassment, even if it does mean something more than a passionate desire to win the next general election too. Ross is very convincing about the nature of the rapport between Blair and Clinton and the genuineness of Blair’s populism, penchant for self-made multimillionaires, and pleasure in throwing parties at Downing Street for pop stars. I ask a question, ‘Whatever happened to Labour’s commitment to the principle of progressive income tax?’ to which Ross replies that he doesn’t know either. Afterwards, I describe to him what I see as the irony of Gordon Brown removing tax concessions from occupational pension schemes in the same breath as proclaiming the need for people to save more than they presently do for their old age. Politics as usual, I suppose.

20 January. Run into Derry Irvine at the National Gallery. After the exchange of a few pleasantries about tumbrils and guillotines, he says (‘to be serious’) that an unholy alliance appears to be forming between the Labour Left, who want an elected House of Lords because it would be ‘democratic’, and the Conservative Right, who see ostensible support for the principle of election as the best way to stall the whole thing (reckoning, no doubt, that the House of Commons would recoil, as it has before, from the prospect of handing serious power to a quasi-duplicate of itself).

21 January. Having been persuaded at the last minute by Jeremy Fairbrother, the bursar of Trinity, to attend the Lords for the committee stage of the Bill on Higher Education, I find the timetable evidently awry and only eloquent Conrad Russell and pugnacious Colin Renfrew holding the fort for the higher professoriat. No chance to make the remarks I had been rehearsing about the irony that this Government might succeed as well as the last in souring its relations with the universities to an unnecessary degree. I am reminded of sitting next to Norman Tebbit at a Chamber of Shipping dinner in the Eighties when he assured me that the universities ‘have let down the country’. I asked Tebbit if he wanted my college, which has a famously imposing roll-call of Nobel Laureates, to stop winning Nobel Prizes. Unsurprisingly, I could extract neither a yes nor a no.

22 January. To the Lords to make a speech about Individual Savings Accounts in my capacity as deputy chairman of the Financial Services Authority. I suggest as tactfully as I can that ISAs, which appear to have been thought up by ministers and their personal advisers without any proper consultation with either regulators or officials, will pose some serious issues of investor protection. As usual on such occasions, the chamber is empty except for those who have likewise chosen to speak in the debate, and what we say is quite predictable to anyone who knows where we’re variously coming from. Next morning I am intrigued to see a Guardian article talking about a potential ‘scandal’ and find to my astonishment that it is my speech being written up. The implication is that I said that ISAs could seriously damage investors’ financial health when what I actually said was that I was doubtful about the life insurance component since, as everybody knows, early encashment of life policies can seriously damage etc. Journalism as usual, I suppose.

3 February. We take Eric and Marlene Hobsbawm out to dinner to celebrate Eric’s CH; suitably, the restaurant is a few doors away from where Engels has a blue plaque. We discuss the widely different political trajectories of the undergraduate Communists of Thirties Cambridge. Eric says he never minded being called a Leninist, but always refused to be described as a Stalinist. We subsequently discover that the day he goes to Buckingham Palace to get his CH is the day a bit of the ceiling falls in.

5 February. Ray, the barber to whom I go for a haircut in Cambridge, tells me how many of his clients who voted enthusiastically for Blair are now complaining about him. But Ray’s clients aren’t being picked up by the Mori pollsters, are they? I am reminded of Disraeli saying in May 1881, the year after his landslide defeat by Gladstone: ‘The Ministry seems in all sorts of difficulties, but I don’t think scrapes signify to a government in their first year.’

8 February. At lunch with Roy Jenkins, I take the opportunity to ask what he would feel if I were to publish his telling me his surprise (and mild disapproval) at hearing Derry Irvine address the Prime Minister to his face as ‘young Blair’ at a Chequers weekend. Roy says, ‘No, I don’t think I’d mind that,’ and goes on to describe how relations between the members of Harold Wilson’s Cabinet deteriorated from the day that Wilson told them all to use first names rather than departmental titles. Fellow guests include Eric Anderson, who describes himself as having been Nolanised for a forthcoming quangoid appointment in succession to Jacob Rothschild and says it will stop people saying he got it because he was Tony Blair’s headmaster. My wife responds that if they’re going to say that, they’ll say it anyway – and we hadn’t even seen the famous ‘Teacher’ ad on TV.

9 February. News of the death of Enoch Powell brings back memories of my only two meetings with that remarkable man. On the first occasion he came to talk to an academic dining club at the LSE and (as I recollect it) trounced his left-leaning discussants pretty decisively. When he arrived, the West Indian waitress looking after us went up to him with a big smile and said, ‘Can I believe my eyes?’ to which the expressionless reply was: ‘Gin and tonic, please.’ The second was when we were fellow guests with him, his wife and Mo Mowlam at dinner with Frank Field. Enoch covered much of what turned out to be familiar ground: his conviction in the Thirties that there would be another war with Germany, his expectation that it would be another trench war and that he would therefore be killed in it, his certainty that he was never physically at risk going about his Northern Irish constituency unescorted, the poems written every year to his wife on their anniversary – all conveyed in his mesmerising flat voice with its half-provincial, half-colonial accent. There was only one moment when it was difficult to control facial expressions: Enoch saying that he couldn’t bear sitting opposite Anthony Wedgwood Benn because of the mad look in his eyes. I am slightly disconcerted when Enoch says to me as we part in the street outside Frank’s flat that he has enjoyed ‘an evening back at Trinity’.

23 February. Enjoyable conversation with Robert Chote of the FT, who has just written a piece for the magazine Prospect about Gordon Brown, but not with co-operation from the subject. We discuss Brown’s mixture of unmistakable ability and equally unmistakable distrust of those who aren’t in his inner circle. Robert goes on to describe Geoffrey Robinson’s performance at the press conference called to launch ISAs: whenever a question was asked by a knowledgeable financial journalist which showed that Robinson hadn’t begun to think the details through, Robinson’s response was to say: ‘I wouldn’t concentrate on that aspect if I were you.’

2 March. Back to the restaurant du côté de chez Engels with our son and daughter-in-law. Our son is preparing the lectures he will give on political theory next academic year in Cambridge and has been reading the recent writings of Tony Giddens, the new director of the LSE, who, according to the New Yorker, is Tony Blair’s favourite intellectual. I comment that I can see why Giddens’s recycled platitudes and woolly prescriptions appeal to Blairites, but wonder why a prime minister who has got where he has by not being ideological needs a tame ideologist. Am reminded of Nietzsche’s remarks about the kind of intellectuals who used to be in the service of princes and now serve political parties instead.

12 March. Discussion with some like-minded cross-benchers about House of Lords reform. It seems the majority of cross-bench hereditary peers feel as I do that heredity is anachronistic and untenable, but want our abolition to be combined with simultaneous implementation of a properly considered new system. Might there be an unhappy hiatus of indefinite duration during which the advising and revising chamber is arbitrarily packed with ‘Tony’s cronies’? Somebody comments on the irony of Blair’s simultaneous endorsement of a hereditary monarchy. I reflect that whatever Blair thought he meant when he called poor media-exploited (and exploiting) Diana the ‘people’s princess’, it was marriage to the heir to the throne which made her into an icon – as per textbook anthropology.

14 March. To dinner with the Dworkins to meet Jürgen Habermas. Habermas says that the German universities have still not recovered from what the Nazis did to them – and that in a country which had once been indisputably pre-eminent in science and scholarship alike. I reflect not for the first time how lucky I am to have lived my life in a country where politics has been so mercifully unimportant in comparison.

15 March. Talk with Roy Jenkins and John Fleming about New Labour’s attitude to Oxbridge. I describe having run into Keith Thomas in Oxford a few weeks ago, who was very funny about the dons all busily transferring their assets into their wives’ names in the expectation that their world will shortly be coming to an end. Roy says that some of Blair’s colleagues’ resentment of Oxbridge is creating a problem that Blair could well do without. But does Blair, I wonder, really care about preserving standards of excellence in science and scholarship any more than the dreaded Margaret Thatcher did?

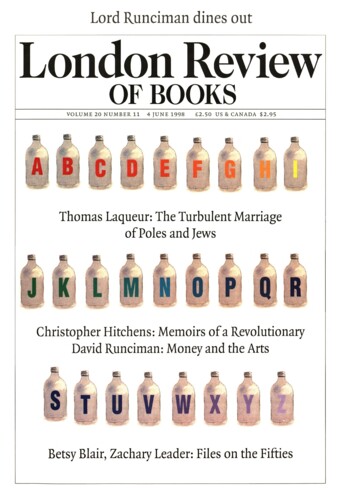

8 April. To the LRB to discuss with Mary-Kay Wilmers whether this ‘political’ diary is worth publishing, since despite the omission of some highly readable conversations which have inevitably to remain confidential, what’s left might still cause offence without being sufficiently interesting to justify it. I ask: mightn’t I do better to keep it for my Nachlass? She answers: no.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.