The speechless quality of music is much envied and imitated. Spoken language follows in music’s wake, verbalisation a poor second best. The musical metaphors of Romanticism are steeped in linguistic paralysis: as in Shelley, where music ‘vibrates in the memory’ only when ‘soft voices die’. Now, though, with sledgehammer subtlety and schmaltz, music, the piano in particular, tends to be invoked for all the synaesthetic reverberations it can offer. Clichéd images of the musician as mute genius or emotional pygmy crop up everywhere, and bad scripts are bailed out by sonorous soundtracks. Films – the Helfgott biopic or Jane Campion’s truly abysmal The Piano – acquire gravitas by replacing all shades of grey with the stern black and white of the keys. Normally it’s just a cop-out, borrowing the sonorous qualities of one art-form to make up for the artistic failings of another.

Bernard Mac Laverty’s strength has always been his linguistic focus on minutiae, his depiction of the parochial through luminescent language. Lines from his short stories fizzle in the memory years after we read them. There’s the Grandmaster in his collection Walking the Dog, described – in a curiously Irish way – as ‘leaning down confidently, pointing out the sins, advising for the future’. His favoured forms have been the short story and the novella (he has published four collections of stories), his elegant simplicity needing no grandiose themes or schemata to shore up the taut narratives.

His two previous novels, Lamb and Cal, rely on the most frugal plotting: since the crime has already been committed (the abduction of Owen Kane, the killing of Robert, the RUC officer), the narratives are internalised – rueful accounts of the lives of good but guilty men. The action is economical, the characters entirely engaging: both novels were made into successful films, full of psychological insights, unravelling relentlessly until either death or arrest.

Part of Mac Laverty’s attraction was his muddying of the moral waters: ‘it wasn’t like 1916 in 1916,’ says Cal when he is being pressed into service with the IRA. There is a stunning description of him working the land:

The only colour in the landscape was the red and blue of the plastic baskets they were collecting into. Everything else was the drab blue hue of potatoes, from their clothes to the field itself with its withered buff potato tops lying flat on the ground. Occasionally he would come across a potato split by the tractor and its whiteness and cleanness were a relief to the eye.

The drabness is first expressed in (suspiciously British) primary colours, the idea of a rustic Irish existence belied in the bright red and blue plastic. Even the split potato, an evocation of Ireland divided, is a relief to the eye of the Republican. ‘It was funny, Cal thought, how Protestants were “staunch” and Catholics were “fervent”.’

Grace Notes opens with similar insights: ‘Somewhere a man was whistling – at least she assumed it was a man. Women rarely whistled’. There are Mac Laverty’s usual fragmentary observations: ‘Somehow talcum powder had got onto her left shoe and dulled the leather. She wondered how it had survived the rain.’ He records the daftness of intimate family gestures, like those of a father waving goodbye with his handkerchief: ‘then he operatically dabbed his eyes with it, then, such was his grief, he pretended to wring it out.’ He likes playing word games, the ‘bar talk’ from a pub transmuting into ‘Bartok’, Lynn C. Doyle into ‘linseed oil’. Cal swears in French whenever his guilt or nerves give way; in one instance he reveals his self-hatred in the expletive series: ‘Merde. Crotte de chien. Merderer.’ Mac Laverty’s diction is part of a linguistic exhumation, a verbal archaeology: the ‘whorl’ of an ear, the ‘tuggy’ toast, someone ‘thran’.

The heroine is Catherine McKenna, a pianist and composer returning to Northern Ireland for her father’s funeral. She is estranged from this background, having moved to Islay to teach and compose. She has met a man there, the alcoholic Dave, and had a daughter, Anna. The book is divided into two halves. The first recounts Catherine’s return to her former home, and the embarrassed confrontation with her mother; the second describes her life on Islay up to that point: the romance on the island, the birth of her daughter, her alienation from Dave, and then the triumphal performance of her composition on the radio.

The title itself hints at random jottings of words as against the specifics of the stave, the notes. A grace note is one that is melodically and harmonically inessential. But instead of looking at the theoretical dilemmas of representation, the speechless quality of music against the spoken grotesquerie of words, Mac Laverty goes for emotional overload, labouring the musical metaphor through every page. Instead of giving his novel form and frisson by opposing the ineptitude of words to the score, each sentence is bloated with ‘musical’ significance, full of import. Symbolism has to be unexpected if it is to be effective, offering a surprising synchronicity, a hint of order amid chaos. In Cal, every time a knee is mentioned, in the kneeling at Mass or the knee-capping of a joy-rider, we are reminded of the ‘genuflection’ of the dying man, falling on his doorstep, calling for his wife. But if symbolism hits the reader in every phrase, and every metaphor is musical, the result is cloying; the conceit conceited. In Grace Notes ‘the curtains hung silvery-grey columns, like organ pipes’ is a typical simile; childbirth is ‘a bit like composing music, really, parading the personal as they all stood at the bottom looking at the pain which was now cracking her open’; pregnancy is like being ‘fitted with a Lambeg drum’. The result is a tasteless sandwich with, lurking between the white-slice prose, the spam of the ever-portentous piano: Catherine is writing a series of haiku for piano, bizarrely based on Vermeer’s paintings of interiors, or ‘maybe more about the women in the rooms’.

Catherine was born in a nursing home called Malone Place, except that of course the M had dropped off the sign, so it was – wouldn’t you know it? – ‘alone Place’. The music she composes for the BBC is called ‘Vernicle’ – a badge worn by pilgrims – and uses the Lambeg drums worn by Orangemen on their marches. Such unleavened symbolism is typical of a novel that yokes together every conceivable modish theme: Northern Ireland, feminism, motherhood, music, post-natal depression, alcoholism. It turns Catherine into a cardboard cut-out character, a vehicle to express the themes of a novel seemingly put together by a panel from Woman’s Hour.

This heavy-handedness, the yearning for significance, hinders the dialogue, as well as the passages of indirect speech. Trying to divert her mind from paranoia about her daughter, Catherine thinks to herself – as one does – that ‘Alasdair Kirkpatrick in a tutorial said that in Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights ...’ Mac Laverty has a carpet-bombing approach to composers and critics: ‘as Nadia Boulanger says’; ‘it was a form Purcell seemed to like.’

Like the Holly Hunter character in The Piano, Catherine is entirely dislikeable, a self-righteous, self-pitying, music-mother figure. In fact, Mac Laverty explicitly borrows the imagery of Campion’s film, the rogue Dave treating Catherine as a sex object (‘we never ... do it these days,’ he says through his usual haze of alcohol) and then attempting to slam the piano lid on her delicate fingers: ‘she felt the wind of the slam on her fingernails. The bang of the lid was like a gunshot. Every string in the piano vibrated for a long time.’ Such gender stereotyping is tiresome enough, and somehow more galling coming from a man: ‘That’s all men were really –’ says Catherine, ‘three-legged stools. Two legs and the other thing. A dick.’ One episode in particular brings tears to the eyes – for entirely critical reasons. Catherine is hanging up the washing and clamps the peg on the crotch of her lover’s Y-fronts: ‘she hoped it would hurt.’

Artistically, too, there’s a false ring to the interior monologue: ‘But the only shoes she had brought down were brown. With navy tights. And a black skirt. Oh God – what a combination.’ Then again: ‘Her period was due ... a woman was synchronised to the moon and there was nothing she could do about it.’ This sounds like a parody of what men think women think: do they really boast, as Catherine does, that ‘a woman was in tune with the tides’? How different is a line from Cal, written from Cal’s disgusted viewpoint, as he holds a girl close for a slow dance, making sure he is seen because he needs an alibi for the crime he has just committed: ‘She was not fat but he felt the indentation her bra strap made in her back.’ The girl chews gum, and the dark mole beneath her chin has a curling blond hair emerging from it. It is a beautiful scene, in which the innocent woman is not idealised nor the guilty man demonised.

Then there’s the tedious political point-scoring, Catherine complaining (when someone inadvertently refers to the composer in the masculine) that ‘He’s a she. He’s me,’ and worrying that composers are called ‘masters’. With Mac Laverty mouthing this ‘all men are bastards’ mantra, it was unwise to let Dave (the male fall-guy, the foil for the more sensitive femininity of drippy Catherine) have the best lines in the book. As part of her emancipation, Catherine wants to learn to drive, but – and this seems an eminently fair comment, given that Catherine spends most of the novel weeping – ‘Dave refused to teach her in the van because he said it could only lead to fights and a fucked-up gear box.’ When they first meet, he asks her if it is McKenna with or without a y. She says without. ‘Good,’ he says, ‘if there was a y in it I couldn’t see where the hell it was going to be.’ This is the gentle kind of humour at which Mac Laverty is so good (in Lamb, the austere Brother Benedict says: ‘the nails tend to get horny with age ... like celibates’). Catherine herself appears to be too earnest for such giggles.

The same tiny moments are described over and over again: ‘The milk had cooled sufficiently for her to drink it from the mug’; ‘she sipped from the far side of the rim. It was no longer hot but it was all she was going to get’; ‘she blew the surface of the milk and tried to sip it, but it was still too hot and burned her lip.’ Simmering cups of tea are touchstones, presumably, of domestic claustrophobia, of habits that never change, but nothing emerges from these Earl Grey moments: it’s as if the novelist had actually set out to describe the drying of paint.

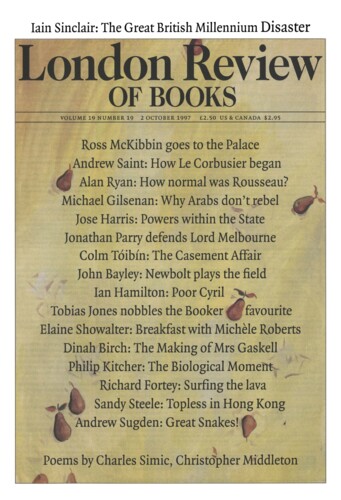

All of which makes the rapturous critical reception of Mac Laverty’s first novel for 13 years the more bewildering. Does the fact that he is now the favourite to win the Booker Prize mean something? Is this the new trend: filigree fiction, in which everything – from simple storytelling to formal invention – is subordinated to the dictates of the fancy phrase and emotional gush?

At one point, Mac Laverty talks of childbirth as being ‘so utterly common and ordinary. And yet when it happened, it was a miracle.’ His previous books had the ability to turn the everyday into the astonishing. With Grace Notes, the writing never leaves the very ordinary, never approaches the music it tries, and fails, to emulate.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.