It is impossible to win gracefully at chess. No man has yet said ‘Mate!’ in a voice which failed to sound to his opponent bitter, boastful and malicious.

A.A. Milne

One loses against strangers in silence. But friends, if they start to lose, inevitably try to strike up conversation. Close friends refuse to resign, so are ignored until mate has been delivered. I was reminded of this a few nights ago, when Russell suddenly arrived in Maida Vale, looking even more manic than normal. At college, he would never sit still, and listened to you with eyes watching what you weren’t saying, the same unilateral way he played chess: he listened as if he was sacrificing pawns, before laying you bare with one line.

But he was at the door, unexpected, at midnight; and more strangely, he didn’t want a game. A few years ago, he would only show after a tour of outpost British polytechnics, having won all the tournaments he had played in. He would bang on my door all excited, certainly drunk, and say: ‘I must try something out on you.’ This time, though, he didn’t mention chess, not for a long time. Normally when he described matches he would just give me his card from memory: ‘The shit opens with Ruy Lopez, so e4 e5, 2f3 c6,’ and so on, expecting me to be with him through every gambit. In chess notation a particularly good move is signalled by an exclamation mark, a move of genius by two: ‘Bxf4!!’ When Russell talked me through games he would show these notations by a series of clenched fists.

He had, apparently, just returned from America, and came straight from the airport, with a tiny bag as his only luggage. I hadn’t seen him since college, but I remember him telling me how he had always wanted to get to New Mexico, just to sit in the sun, watching the rocks and reading The Plumed Serpent. He had flown to New York en route with his girlfriend. Ab was his ultimate muse, quiet but fiercely clever. He used to say that the best moves came to him when thinking about her. ‘And then,’ he started telling me about the holiday, ‘she suddenly said she didn’t want us to be together. She said it, simple as that. Said I didn’t respect her. I took her back to JFK, we had only been there four hours before, and said goodbye.’

Russell would hate Manhattan, he’s too solitary and deliberate. Even their chess he would disdain, with its boggling speed and clinical victories; the swift turnover suits the hustlers, waiting to take money off passing suits, college kids, or joggers too tired to carry on. But he had taken Ab’s unspent dollars, put them with his cash in his back pocket, $400 in all, and, boots kicking out from under the fraying trousers, headed instinctively for Washington Square.

‘You know, I just had this white rage and I knew I couldn’t lose. I felt so determinedly rational, and the only thing I could think was to gamble her money, and mine. It was mid-morning by now, and there were twenty or thirty men – some drinking already – shuffling up and down the lines between the tables with small wads of cash in their hands.

‘The games were really fast. No clocks, no writing down. No hesitation from the ones, on the far side, who were obviously the regulars. Nearer me were idlers, just intrigued or watching on the way round, some taking up the challenge, putting money in the drawers under the boards. None of the games lasted more than ten minutes.’

Russell always used to say that chess was only ever a variation on a theme, that players rehearsed openings as if following the rules of courtship, and that it was only with deviation that games turned into interesting, unlikely romances. But there was no stylisation in Washington Square: ‘the pieces were shunted aggressively like so much traffic. It was reckless and intense – exactly how I felt.’

He had stood behind the end table, intrigued by an elderly man who sat down, pulled the drawer towards him and raised fifty dollars, smiling as everyone looked at him. He put them down and pushed the drawer the other way, waiting to see if the young, unshaven guy, the regular the other side, would match it. There was no hesitation. The drawer nestled under the board, the pieces above playing for the hundred dollars.

‘It only took a few minutes for the pieces to be almost totally cleared, and eventually the old man shook the other one’s hand, and got up from the table.’ Russell broke off laughing. ‘I should have realised that with the Kasparov game New York would be crawling with Grandmasters, but I was jet-lagged and arrogant and upset, and I grabbed the old man’s arm as he stood up, inches away from me, and told him to hang around. “And then you could buy me a drink,” I said.

‘I sat down, leant across the table, put on my most aristocratic English, and asked if the winner would give me the chance to win back the man’s money. I could see the greed in the guy’s eyes as I counted 40 $10 bills and rested them in the drawer. He signalled to one of his friends, who came across and counted out his own money into it. Then he held out both fists, and I raised my chin silently to his left: the palm opened on a white pawn.’

The guy turned orthodox as soon as Russell started. He played the Nimzo-Indian defence, pulling Russell out of position, forcing pawns to double up on the c-file. Russell replied with the standard Rubinstein variation, pushing up his king’s pawn for central development. As soon as he started describing the game, I knew he had lost all that money. ‘It was too fast for me,’ he said. ‘I couldn’t concentrate. The old man who was waiting to see his money again shook his head at me the same way Ab had done that morning. Before I knew it I was back here.’

I went into the kitchen to fix him a gin and tonic. I gave it to him and asked if he wanted a game. He shook his head. ‘I’m not going to play too much anymore. I want to learn how to do something else.’

It’s odd that a game of finite openings and such well-rehearsed parameters should have come to represent limitless ambition, an exponential growth of possibilities. But if the game (‘sport’, as the snobs say) was immutable, the rules sternly set, there remained – the theory went – the building-blocks to something altogether more numinous. Chess was restrictive, but expansive; it was deiparous. Hence the apocalyptic notices when Garry Kasparov was beaten by Deep Blue last month. The game, it seemed, had been reduced to algorithmic calculation, creativity squeezed from the board by sums and silicon. The sheen had been lost in the most intense combat since Death sat down in The Seventh Seal. A proud Russian had been reduced to calling a computer a cheat.

A typically anthropomorphic complaint: the 64 squares are a sublimation of all human neuroses and aggressions. It’s not a game for four-eyed geeks who increase processing power. It is a stunning, aesthetic sport; serene, silent, almost eirenic. But a board-game all the same, one whose interest lies in its human players’ attempt to be robotic, to make the mind seriously geometric (Orwell, in a complaint that compared chess with socialism, called this the ‘hypertrophied sense of order’). The humans either side are so much more compelling than the board or the scythes of Death and IBM.

The ‘gymnasium of the mind’, in Lenin’s phrase, was a rare arena of free expression in the Soviet Union. ‘No Westerner will become world champion,’ Grandmaster Josef Dorfman, former captain of the Red Army chess team, said a few years ago: ‘all your players are on their own. They have no support from the state.’ Since the crown passed from the exiled Russian aristocrat, Alexander Alekhine, in 1946, only the iconic Bobby Fischer has wrested it from Russia.

Chess is now practised by ominously boring people (like me) who recall classic encounters from centuries ago (Russell’s favourite is the so-called Pearl of Wijk aan Zee, a contest of the present decade, but he will have to wait a long time for some spook to make the same 35 moves that enable him to emulate it). Many cite the ‘Immortal Game’ as their favourite, played at the 1851 Great Exhibition when Lionel Kierseritsky was beaten by Adolf Anderssen with such beautiful, sacrificial chess that he immediately telegraphed the game’s moves to an audience in Paris; others look back to Anderssen’s 1852 ‘Evergreen Game’ in Berlin; others still to the sixth game in the Fischer-Spassky bout in 1972 – ‘the chess equivalent of a Mozart symphony’, people say.

It was probably inevitable that nerds of the world would unite via the Internet. Postal chess, an old favourite, was replaced overnight by online games – vast libraries of previous positions becoming accessible with a few clicks of the mouse. There are endless web-sites (one offered live up-dates on the Kasparov-Deep Blue contest), forums and online conferences. Most influential are the databases used by serious players to study their opponents – to analyse, for example, Karpov’s many losses to the Chigorin defence in the Seventies.

Against this massive codification, a freestyle form has emerged: samurai chess.* It invokes Miyamoto Musashi’s classic tactical treatise of the 17th century, Go Rin No Sho (A Book of Five Rings), and replaces Nigel Short’s notorious TDF game-plan of (‘trap, dominate, fuck’) with haikus and aikido tenets (‘If pulled, enter. If pushed, turn’). Zen training to cultivate the quality of fudoshin, the ‘imperturbable mind’, is offered as the perfect blend of discipline and flamboyance for successful chess.

Kasparov is renowned for his fitness regime, but Samurai chess takes the mens sana message to martial-art extremes: physical stretching, weight-lifting, breathing and meditation are all advised as part of the yellow brick road to better chess, plus of course Shizentai (‘natural posture’). Diet, too, can help, but that isn’t new. The Italian Carrera wrote in 1617 that before a game one should ‘abstain some days from meat to clear the brain ... take both purgatives and emetics to drive the humours from the body ... above all be sure to confess sins and receive spiritual absolution just before play’.

Instead of thoughts of castling, passed pawns, forks and discovered checks, martial arts offer the mind the aims of atemiwaza (‘striking techniques’) and de-ai (‘timing’). The reverse implication seems to be that, with all his mental fine-tuning, a Grandmaster might be useful by your side in a pub brawl, that – underneath it all – Kasparov bristles like Bruce Lee. The glossary talks about ‘the Force’ (as in Star Wars) in the same sentence as ki, chi and prana (Japanese, Chinese and Indian ‘currents of vital power’) as if Yoda himself might have played a mean game.

For all this bizarre splicing of disciplines, however, chess is as intuitive as it is analytical. Asked how many moves he considered before making a decision, Bobby Fischer replied: ‘one, the right one.’ Kasparov speaks of ‘navigating by your imagination and your feelings, playing with your fingers’.

By contrast, computers – at least the ones more shallow than Deep Blue – tend to play for points rather than position; they have difficulty negotiating the tactics of sacrificial chess, and are so programmatic in the openings, play so blatantly by the book, that they can often be thrown by what might otherwise be considered a dubious move (following up 1 d4 d5 with the unconventional 2c3 – rather than the c4 of the Queen’s Gambit Declined – gets the computer off your scent). They never make errors of calculation, but rarely create spectacular openings. It’s like no-score-draw soccer: attritional and dull.

So as an antidote to all the computer anxiety, to all this Luddite talk about IBM’s eight-year-old, six-foot-five prodigy (next career ‘molecular dynamics’, says the press release), it’s interesting to note that the Troitsky Line, formulated at the start of this century, has only recently been ‘proved’ by endgame databases. Like Fermat’s Last Theorem, the complicated formula which enabled the Russian (naturally) analyst and composer to work out the line behind which a pawn must be to be defeated by two knights was only understood very much later. In chess, human minds are always ahead of the game.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

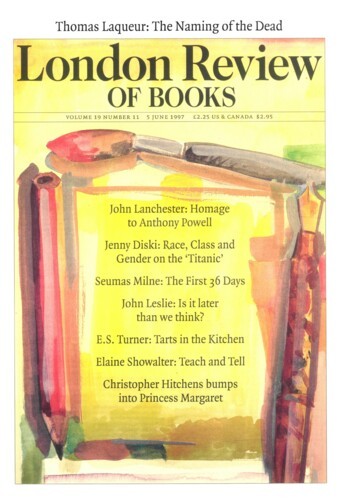

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.