Iam not entirely content with the degree of whiteness in my life. My bedroom is white; white walls, icy mirrors, white sheets and pillowcases, white slatted blinds. It’s the best I could do. Some lack of courage – I wouldn’t want to be thought extreme – has prevented me from having a white bedstead and side tables. They are wood, and they annoy me a little. Opposite my bed, in the very small room, a wall of mirrored cupboards reflects the whiteness back at itself, making it twice the size it thought it was. In the morning, if I arrange myself carefully when I wake, I can open my eyes to nothing but whiteness.

If I trace it back, that wish for whiteout began with the idea of being an inmate in a psychiatric hospital. White hospital sheets seemed to hold out the promise of what I really wanted – a place of safety, a white oblivion. Oblivion, strictly speaking, was what I was after, but white hospital sheets were an approximation, I believed.

Actually, the reality of the hospital in London was rather different, though the sheets were white. The near-demented Sister Winniki (identical twin of Big Nurse) always ripped the crisp white sheets off me at too early an hour in the morning, in the name of mental health. ‘Up, up, up, Mees Seemonds. Ve must not lie in bed, it vill make us depressed.’ I was depressed and all I wanted was the right conditions for my depression, but we weren’t allowed to be depressed in the bin. I had to battle against Sister Winniki to achieve even a modicum of oblivion – but since the whole point of oblivion is that it is total or not at all, I couldn’t win.

When hospitalisation failed, I transferred my fantasy to the idea of a monk’s cell. But there wasn’t anywhere I could go with the fantasy, being both the wrong religion and the wrong sex, so I settled maturely – compromisingly – for making my almost blank bedroom and achieving at least my morning whiteout. It’s something, but not quite enough. Though I’m very good at getting what I want, the world is better at not letting me have more than a taste of it.

Finally, it came to me, effortlessly, as these things seem to come. Suddenly, there’s a moment when a thought in your head makes itself known as if it’s always been there, as if you’ve been thinking it for ever. Sometimes I think I don’t think at all, if thinking means some conscious process of the mind working out the nature and solution of a problem. I’m a little ashamed of this. I wish I thought properly, like proper people seem to think.

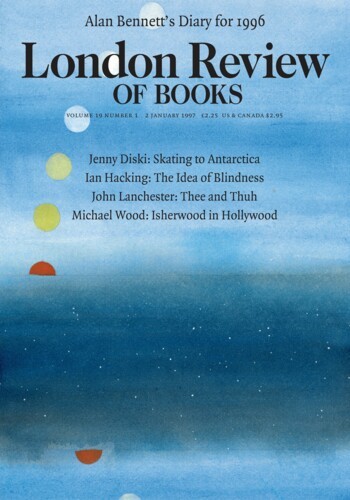

I reasoned with myself: throughout the history of the world very, very few people have been to Antarctica; there was no reason why I, just because I fancied it, should be among them. It wouldn’t be an outrage if I didn’t go to Antarctica, almost everybody didn’t. Nothing bad would happen if I reached the end of my life without having been there. But I was, nonetheless, outraged at the idea of not going. Irrationally but unmanageably outraged. This is very important to me, I replied to my reasoning self, but I was unable to explain why.

The Arctic would have been easier, but I had no desire to head North. I wanted white and ice as far as the eye could see, and I wanted it in the one place in the world which was uninhabited. I wanted my white bedroom extended beyond reason. I wanted a place where Sister Winniki couldn’t exist. That was Antarctica, and only Antarctica.

It turned out not to be so easy to go to Antarctica. There isn’t anywhere exactly to go. But like thoughts that pop into your head, classified advertisements make themselves known when you’ve got something on your mind. ‘Antarctica – the cruise of a lifetime,’ it said. I sent off for the brochure. In the meantime, I called the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge.

‘How can I get to Antarctica?’ I asked.

‘Are you a scientist?’

‘No, I’m a writer.’

It sounded feeble next to the echo of ‘scientist’. The woman at the BAS clearly agreed.

‘You can’t go if you’re not a scientist engaged in specific research.’ Was she a relative of Sister Winniki?

‘Why not?’

‘Because the British Antarctic Survey is set up to protect the environment for serious scientific purposes.’

‘What about serious writing purposes?’

She said she could arrange for me to interview people who have spent time on British Antarctic bases.

‘Have you thought about having a writer in residence?’ I wondered.

To say she put the phone down wouldn’t be quite true, but the conversation terminated.

I am not averse to disappointment. It has its own special pleasures. Disappointment is the hidden agenda within fantasy, a nugget for the aficionado who might trick up the bland negativity of the word by sliding alphabetically towards disjunction and disparity. If you could have what you dream about, if I could have Antarctica all white and solitary and boundless, there would finally be no excuse. Imagine, you are exactly where you want to be; and now what? Yes white, yes solitary, yes boundless, but will it, in its icy, empty, immense reality, do? In my head, it does fine: why seek out the final disappointment which the earlier, smaller disappointment only seeks to prevent? The point of desire is desire itself, the essential pleasure in expectation is expectation. The idea that reality is a completion of the wish is fallacious. It is only our dim literal-mindedness that makes us believe that we should try to achieve what we wish for. The disjunction between what I want and what I can have is my friend, my best friend in all likelihood, and I know it. Disappointment is a safety net to be relished in a secret, knowing way by the disappointed. Give thanks for the BAS and all the other preventers of fantasy come true.

The brochure arrived and I reset my daydreams.

Some realities you cannot get away from. I learned that, repeatedly, from the age of two at Queen’s Ice Rink. An ice rink is a promise made purely for the pleasure of creating disappointment. If you want to skate without stopping you have to go round and round the bounded ice; you can’t go on and on, even though the surface permits a gathering of speed which can only be for the purpose of heading forwards without hindrance.

I’m not entirely ill at ease with boundaries. I was a city-bred child and boundaries are the nature of the city. Pavements stopped at kerbs and became roads, requiring a change of direction if I was on my tricycle, or a change of attention if I needed to cross to the next section of pavement. There were stopping places, turning points and breaks in the cityscape on any journey.

I lived on an island on an island. What I knew about the larger island was that if you went on in any direction there was sea at the edge of everywhere – the notion of a change of country without a watery division was astonishing to me. When I was very small we went to Belgium and drove to Holland one day. I couldn’t credit the unreality of it. It was the sea that said a country was a country, not an official checking passports at a border. And where were we, I wanted to know, when the car was half-way across the line dividing Belgium and Holland? ‘It depends,’my father riddled, ‘whether you’re sitting in the front or back seat.’ This was interesting, because I always sat in the front passenger seat next to my father when the three of us were in the car. My mother sat in the back. Always. Under the peculiar circumstances of the Belgium/Holland border, my father and I were a nation apart from my mother. I swivelled in my seat at the critical moment as we crossed into Belgium again that evening. ‘You’re still in Holland,’ I told my mother, but even as I spoke she arrived back in Belgium with us.

The island within the greater island was a block of flats on the Tottenham Court Road. Paramount Court. It is still there, I pass it in the car once or twice a week. I lived in Paramount Court with my mother, and, when he was there, my father, from the time I was born until I was just 11, which is to say 1947 until 1958 or thereabouts. Until I was seven we lived in a two-roomed flat on the third floor, facing the well at the back, then we moved upstairs to the fifth floor, to a three-roomed flat at the front, where I had a room of my own for the first time. Tottenham Court Road has changed. The traffic is one-way now and there’s much more of it; the cinema was pulled down years ago and the space remains unplugged, although it’s designated for the new hospital which will replace University College Hospital and the Middlesex. There were then, of course, no electronics shops, there being nothing in the way of electronics in the Fifties.

The corridors inside the flats, the back alleyways, the cinema, and the skirt of pavement around the island were my playground. It never crossed my mind that my domain was limited in any way. The bareness of the narrow, cream-coloured, empty corridors, the neutral carpet and the unadorned pavement was decorated and redesigned every day with whatever landscape I chose for it. It felt enormous, limitless, available for any purpose I wished to put it to, and filled with both familiarity and surprise. Even now I can’t imagine any suburban or country childhood that would have provided me with so much. I spent a lot of time wandering, playing on my own, but there were other children in the block with whom I played in the spaces of the flats. Helen, Jonathan, Susan, whose doors I knocked on, with whom I would have tea sometimes, who, occasionally, would have tea with me in my flat. So, I still dream about getting back to roam in the corridors, to climb the fire escape, to play the games and tell myself the stories I invented in my childspace.

Prince Monolulu, who has since become a pub, lived in Fitzrovia and was a regular passer-by. He was immensely tall and ebony black. He wore exotic flowing robes (exotic, that is, for those days) and always had brilliantly coloured cock feathers in his hair. He was a racetrack bookie and a professional character. When we met on my pavement, he’d yell out his catch phrase ‘I got a hoss. I got a hoss.’ And we’d fall into each other’s arms.

Inside the enclosing walls of Paramount Court I began life with parents who were cash rich. The profitable days of the black market were still making it possible for my father to bring plenty of money home, and the remains of the jewellery my mother had from her first husband were sold off to keep her feeling wealthy when the black market came to an end. For the first three years of my life, my mother’s desperate need to display wealth was taken care of. Of all things in her life, I was the best medium for her display – she went abroad for my woollen vests, dressed me in velvet-collared coats like the little Prince and Princess, and made sure I always wore white gloves and had immaculately ironed satin bows in my hair. When the money dried up, my mother struggled to maintain my appearance – the white gloves were the last thing to go.

As I recall, it was my mother who took me skating. Every day, long before I was old enough to start school. You could skate before you could walk, she would say when I was older. Feet don’t skate, but they experience skating. You sense the solidity of the ice through the blade in a way that is quite different from being on any other hard surface. Concrete doesn’t feel as ungiving and absolute as ice. And yet, to skate is magical, as you find yourself coasting free and frictionless. The clear distinction between yourself and the ice you are on strengthens the sensation of your own body, and of its capacity both for control and for letting appropriate things happen. And for all the impression of physical mastery, skating is still strange and dreamlike. Dreams of flying are the nearest you get to the feeling of being on the ice.

Every hour the skating stopped and a machine was pushed up and down the ice, like a lawn mower, to smooth it. Underneath was pure, untouched surface again, gleaming, milky-white, virgin, immaculate ice. For 15 minutes after this the rink was only for serious skating; people practising what they had learned during a lesson, and rehearsing dance routines to the music coming from loudspeakers. In the middle, figures were skated, and I would go on with a handful of others and practise making 2s, 3s, 4s, all the single digits, appear in the silky new ice. This was another kind of skating, not going anywhere, rather meditative, concentrating on the ice at your feet to assess the quality of the marks that were appearing under your blade. These figures were the building blocks of the kind of free and flashy skating I wanted to do, I was told. They would teach me balance and control on the ice. The figure 2 had me turning and leaning so that I could eventually skate in just the way I wanted, but I had to work at it to get the technique right. It was boring making 2 appear over and over again on the surface of the ice when I could have been flying free.

Now, I like the idea of that slow, concentrated, meticulous and pointless activity. Eyes down watching the blade and glancing behind to check on the quality of the mark you have made, seeing it not quite correct, not bulbous enough, or unevenly rounded, finding the tail too elongated, not sharply enough defined, and beginning again to make it better, eventually to make it right. It’s that I imagine myself doing now.

My mother didn’t find my endlessly practising figures on the ice pointless, she was willing to sit day after day in the chilly seat beside the barrier. The figures were for her, as for my skating teacher, a means to an end. They would make me the new Sonja Henie the skating champion turned skating movie star. I would be the youngest champion ice skater ever, and she would be the mother of the champion. My mother dreamed of making me into an ice princess, but something went wrong. After a while I refused to practise, and life, in any case, got in the way. What she got, to her bitter disappointment – though I think the irony might have been lost on her – was an ice maiden of another kind altogether.

I last saw my mother on 22 April 1966. I remember it because the last time I saw her was two days after my father died. The date in my memory is the date of his death.

When I was 14, I had been admitted, after an overdose, to the mental hospital in Hove, where I stayed for four and a half months, stuck, because the psychiatrist in charge wouldn’t let me live with either of my parents. My father was in Banbury, my mother in Hove. The mother of a school-friend had heard about me and offered me a home in her house in London, which I, the psychiatrist and both my parents gratefully accepted. When my father died I was still living in her house, aged 18, and two months away from taking my A levels.

Two days after my father died, my mother came through the front door and handed me an umbrella. A gift. For April showers and stormy weather. It wasn’t any ordinary umbrella, it was pale, powder-blue and shaped like a pagoda, its spire rising to a delicate point, and all around the base was a scalloped frill made of a matching powder-blue artificial, chiffon-like material. Look for the chiffon lining – blue skies, nothing but blue skies – on the sunny side of the street – every time it rains it rains pennies from heaven – come rain or come shine.

My mother sat down to lunch. She was almost feverishly elated. She was pleased he was dead. It served him right for being the bastard he was. And she wasn’t a hypocrite. She’d always said, hadn’t she always said – she had always said – that if she saw him lying dead in the gutter she’d kick him out of the way and walk by. And that’s what she would do if she saw him now lying in his coffin.

The woman I was living with was present and at this point, thinking I needed something more than a blue umbrella, reminded me about an A-level class I had to get to. I’d better hurry, she said, or I’d miss it. I hurried so much getting out of the house to the non-existent class that I forgot to take any money with me, so I wandered down to Camden High Street and sat in the library, prepared to give it a couple of hours before my mother ran out of steam and went on her way. The library had a large plate-glass window, and my mother, instead of turning left to the nearest tube and bus stop when she got to the High Street, inexplicably turned right and walked right past it. Not actually past. She was already screaming when she pushed through the doors. I sat in silence while she shrieked and wept, noisily enumerating my faults, not the least of which was being just like him: a liar, deceitful, treacherous, heartless. True, actually, in this context. Then she departed, her aria over, leaving the library in a silence it rarely achieved in the normal course of the day. I never saw her again.

Whenever, in the past thirty years, people asked, as they do in the regular way of introductory conversations, about my parents, I said my father died in 1966 and that I hadn’t seen or heard from my mother since the same date. Often, incongruously to my mind, they would ask me if she was still alive. ‘I don’t know,’ I’d reply.

‘But don’t you want to know?’

‘No.’

‘You must,’ some soul brother or sister of Sister Winniki would insist.

There seems to be no limit to the reach and power of popular psychology. Everyone now knows that mothers are an essential item of equipment in any psyche, and that though relations with mothers may be difficult or even dreadful, attachment to them is mandatory. They also know, as a corollary, that a denial of attachment is a failure to confront the reality of mother-attachment.

‘You must find it very disturbing.’

‘No, I find it delightful.’

However, I am not immune to the power of popular psychology, for all my doubts and irritations with it. I knew what I felt about my mother’s absence, but suspected that what I felt must be an avoidance of the real feelings everyone else supposed I naturally would have. Bad feelings, sad feelings, guilt feelings. Those kinds of feeling. From time to time, in the cause of self-knowledge, I would excavate, try to dig down below my contentment with the situation, but beyond the strong wish for the situation and therefore my contentment to continue, I could find no underlying seismic fault waiting to open up. Of course, psychoanalytic theory has a ready answer to this – how can I possibly know what I don’t know I know? There’s no argument against this one. Still, there were a few things I did know about myself which might equally have been concealed from me by me, and some of those things gave me pain and difficulty. Perhaps the continuing enigma of my absent mother shielded me from something worse, uncopable with. Indeed it did, it shielded me from her if she happened still to be alive. But if that was the case, then shouldn’t I have been grateful to my unconscious for the protection it provided? Surely, it is neurotic to seek pain, where ordinary unhappiness is available? I gave up searching for anguish and settled for naive tranquillity. What I didn’t know didn’t seem to hurt me.

For the most part, quantum theory has been of little practical use in my life. When shopping in Sainsbury’s, trying to get out of bed in the morning, or wondering what to wear, quantum theory is hardly any help. In one area, however, it has had a remarkable relevance. With all due acknowledgment to Erwin Schrödinger, let us do a thought experiment. Imagine a box, inside which is a flask of hydrocyanic acid, some radioactive material, a Geiger counter – and my mother. The apparatus is wired up so that if the radioactive material decays, the Geiger counter will be triggered and will set off a device to shatter the flask and thereby kill my mother. We set the experiment up, shut the lid of the box, and wait until there is a precise 50:50 chance that radioactive decay has occurred. What is the state of my mother before we open the lid to look?

Common sense says my mother is either alive or dead, but according to quantum theory, events such as the radioactive decay of an atom and therefore its consequences become real only when they are observed. The case is not decided until someone opens the lid and looks. The condition of the radioactive material in the closed box is known as a superposition of states, an inextricable mixture of the decayed and not-decayed possibilities. Once the box is open and we look inside it, one of the options becomes reality, the other disappears. But before we look, everything in the box, including my mother, exists in a superposition of states, so my mother is, in quantum theory terms, both dead and alive at the same time for as long as the box is closed.

Since I came across this thought experiment, it has been my view that whatever psychoanalytic theory might have to say about the matter of my mother, it would have to do battle with the Uncertainty Principle before it could fully win me over. The choice on offer is the assumption that for thirty years I repressed curiosity about my mother’s existence because thoughts of her were intolerable, or that, all unknown to me, I was contentedly, not to say harmoniously, living out a recognised phenomenon of the physical universe.

My daughter, Chloe, was halfway through her A-level course when she asked me one day how you find out if someone is dead. I was evasive: as far as I knew there was only one person whose life or death status was in doubt.

‘Find out if there’s a death certificate.’

Funny how easy and obvious it was.

‘I forbid you to do it.’

‘You can’t.’

‘I know.’

Cabin 532 of the Akademik Vavilov was quite as right as could be. Plain white walls, a desk, a bookshelf above it. The bed was a wooden-sided bunk built along the wall opposite the desk, with a pair of beige curtains running across it to close it off from the rest of the cabin. The bedding, to my delight, was all white. Opposite the door was a large rectangular window – porthole, if you must – which opened wide. Nothing else.

While the Vavilov’s engines got up to speed, I lay myself down on the bunk, as contented with the prospect of the next two weeks as a cat with its own private radiator. Indolence has always been my most essential quality. ‘Essential’ in the sense that it is the single quality I am convinced I possess and by which I can be recognised and remembered, and also in the sense that I feel most essentially like myself when I am exercising it. I cannot recollect a time when the idea of going for a walk was not a torment to me; a proposition that endangered my constant wish to stay where I was. I imagine myself, child and adult, curled up in an armchair, reading and being told (as a child) or invited (as an adult) to go out and do something. I cannot think why a person sitting with evident contentment in an armchair causes the desire in others for their immediate activity. As a child I would leave the flat when the cries became insistent and find a safe haven on the back stairs, or at the farthest end of the corridor next to the bronze, latticed radiator, and resume my non-activity. As an adult, especially when visiting people, I used to make an effort, with considerable distress, put down my book, pull on jumpers, jacket and boots (it is always cold when visiting friends) and go for the proposed walk, every step of which seemed a terrible waste of good sitting time. These days, maturity has enabled me to say a firm no, thank you to the proposition. The aim on these walks is to get cold and damp and head for the pleasure of some cosy pub or café before setting off again into the cold and damp to return to the warm, satisfactory haven we had abandoned in the first place. I understand that people like to make distinctions, that to enjoy this they have to interrupt it with that, but I’ve never found it necessary. I cannot see the point of interrupting something which is going very nicely. There is also the matter of landscape, the beauty of it, the freshness of the air, the sense of being part of the natural world – even the sense of being part of the urban world. I do like landscape, but I am quite content to watch it through a window while curled up in my armchair. I wholly approve of rooms with good views. As to the freshness of the air, I’m not so eager for it. Though it is invigorating, I admit, I very rarely have the desire to be invigorated. As to the desire to be part of the natural or urban world: much of the time I know I am part of it, except when I am not sure, but I have not found that walking through a landscape or along a crowded street has ever firmed up my conviction in this area. I’ve lived long enough to know it is a fact that most people find activity useful and confirming, but I am not one of those people; on the contrary, I find it alarming and alienating.

As things stand at present, a phone call initiating activity is never so welcome as the one cancelling it. It’s not routine as such that I cannot abide. There is a kind of intrinsic routine that is the very essence of satisfactory times. When I am alone, at home, I get up, work, eat, sleep, work, sleep, eat, in a pleasurable round dictated by my physical needs. I’m hungry, I eat. I’m sleepy, I sleep. And work, especially the long haul of a full-length manuscript, is not an intrusion, but lives well enough with the physical requirements.

Once I gave it five minutes’ practical thought, it was as easy to get access to the corridors of Paramount Court, about which I had been dreaming for so long, as it would be to find a death certificate, or the lack of one. I phoned the Head Porter and explained that I had once lived there and was now wanting to write about the place.

‘You won’t be knocking on any doors, will you?’ he asked when I arrived. ‘We’ve got a lot of old people here.’

I explained it was just the corridors I was after, but while I was standing in his office, I noticed a board on the wall with the names of the occupiers of each flat. The names Rosen and Levine jumped out at me.

It was a couple of weeks before I looked up their names in the phone book and found their numbers, and a while after that before I picked up the phone.

I introduced myself as Jenny Diski and explained who my parents were and which flats we had lived in. I then reintroduced myself in the silence. ‘Jenny Diski – Jenny Simmonds, I used to play with Jonathan. You are Jonathan’s mother, aren’t you?’

That was when she said, ‘Jennifer,’ and I felt an odd wooziness come over me. I almost said no, not recognising myself by that name. But I had been Jennifer when I was small, though for the life of me, I only really remember being Jenny. I said, yes, but felt fraudulent, which was curious because I never really like being called Jenny. Diski feels more accurately like me, though it is an entirely invented name to which both Roger-the-Ex and I changed when we got married. There was a gasp and then a brief silence.

‘How are you?’

I was 11 when she had last known me, but what else was there to say?

‘I’m well, thank you.’

I explained that I was a writer these days and was thinking about doing a book in part about my mother, that I didn’t know anyone who knew us when we were a family at Paramount Court; would it be possible for me to come and talk to her, to get, as it were, an outside view of what went on.

‘Mrs Levine and Mrs Gold are still here. Do you remember Helen Levine and Marianne Gold, you used to play together? You’re a writer you say? You’re all right, then?’

‘Yes. I’d really like to come and talk to you about my parents.’

There was an awkward pause. I liked the sound of her voice. London Jewish, parents foreign-speaking, brought up in the East End. She sounded alert and thoughtful, you could hear her remembering and considering what she remembered.

‘Well, we were friends of your mother, of course. But ... I’m afraid you didn’t have a very happy childhood.’ This last was said hesitantly, telling me there were things she thought I’d better not know.

‘No, it was a bit of a mess, wasn’t it?’

‘Oh, you remember it, do you? You had a terrible time. I thought you would have forgotten. Well, in that case ...’

The sound of my parents fighting in our two-roomed flat on the third floor echoed through the corridors of Paramount Court, my father leaving several times, my mother being stretchered away to hospital, the furniture and fittings being confiscated by debt collectors when we were on the fifth floor: these were all public events, but somehow, it was assumed, I wouldn’t retain a memory of those things. Adults experience, children don’t.

I remember Jennifer with about the same clarity that I remember the young Jane Eyre, Mary from The Secret Garden, Peter Pan and Alice. Rather less clarity, in fact, since the last four are readily available on my bookshelves and I have reacquainted myself with them quite regularly. Jennifer, I’ve merely remembered from time to time over an increasing distance of years, and with each remembering, each re-remembering, the living, flesh and blood fact of her slips incrementally from my grasp. As a person, she is far less substantial than Tinkerbell, who can be brought back into existence through the will of others. Jennifer does not light up when I clap my hands in recollection; she retains only a dim inner illumination. She did not even preserve her name until very recently.

The thing about Jennifer is that there has been no corroborating evidence for her existence these past thirty years. There are no pictures, no written words; no other person who, remembering her, has spoken to me of her. She has existed exclusively inside my head, only exiting into the world like characters (of whom sometimes she is one) in the novels I write. She is no more certain than any other figment of my imagination. I might have made her up – I did make her up from time to time.

Jennifer began to fade when my father died and my mother disappeared. After that there was no one I knew who had known her, apart from myself. Perhaps the fading was not the first thing that happened. Jennifer became detached, became a separate character, someone with a story of her own. Although intellectually I knew that she and I were one and the same, emotionally she grew distant, acquiring a complete and finished life of her own, related structurally to me but existentially separate. I could recollect her environment with a greater clarity than I could her lived experience. I knew stories about her, incidents that had occurred in her life and I could review them as a series of tableaux, but she was a separate incarnation, not a present remembering self. They say the body undergoes a complete cell change every seven years, and this felt true to me. Jennifer inhabited her own existence, physically other, not me, not part of the continuum of me. I had to doubt the thoughts I thought I remembered her having, even the feelings; perhaps my remembering of Jennifer was like the animation of a puppet, my present retrospection pulling her strings and seeming to bring her to life. Who knows what Jennifer was like, with only my memory as a guide?

My picture of any event occurring to Jennifer always includes Jennifer in the frame. The image is not from her eyes – which is how a ‘real’ memory should be recalled, if such a thing as a ‘real’ memory could be said to exist – but seen from the outside, from some eyes beyond the frame and therefore, unless they are God’s, not actually present at the time of the event. Treacherous, if there is no one to confirm or deny the facts of the event. ‘I’ seem to be remembering an occasion which I, as someone forty years removed from Jennifer, could not possibly have witnessed. Jennifer witnessed and participated in the event, but now she has become part of the image and not the seeing eye she must originally have been. Who is remembering what? When I think of Jennifer sitting on her father’s lap, I see the back of Jennifer, her arms squeezing tight around a silver-haired, moustached, handsome man who is laughing and teasing her. What the hell I was doing there (if that actual moment ever existed and is not just a representation of a general memory), standing to one side, at a little distance from the armchair the two of them are sitting in, no more substantial than a pair of observing and possibly ironic eyes, I cannot say. Jennifer was frightened of ghosts. Perhaps she had every right to be.

Three spruce elderly women in their late seventies and early eighties sat in matching white leather armchairs. I, aged 48, shared the sofa with the one remaining husband. Their hair was dressed, waved and blown dry and their faces lipsticked and powdered. They were formidably well and at ease with themselves. Tea-time. These four, and the two departed husbands, have sat like this, taking tea and chatting, since they moved into the flats in 1940. My mother, at times, would have been among them.

‘Ninety per cent of these flats were Jewish,’ Nathan tells me.

‘Why?’ I wondered. Why this block of flats?

‘The flats had a shelter in the basement. The Jews know how to take care of themselves,’ laughed Mrs Rosen. ‘And there was the rag trade around Great Portland Street, it was convenient for the tailors.’

And the war? The knowledge that the Nazis were just a few miles away, across the Channel? How did that impinge on their daily life?

‘We felt safe here. We were all just 20, and at that age it didn’t bother us. We went to business as usual. To tell you the truth, we didn’t really think about it.’

Mrs Levine recalled an incident that happened on a Thursday afternoon, her afternoon off. It started the ball rolling.

‘Your mother came to my door that afternoon. Somebody was desperately ill, she said, or something like that. I can’t remember. She came up and asked me if I’d like to go to church. I said: why would I want to go to church? But she went. To a church in Trafalgar Square.’

Nathan asked: ‘Why not a synagogue?’

‘I don’t know. She had a reason for going to church. It wasn’t a religious reason, I don’t think. But I don’t know any more about it. It was my afternoon off.’

In fact, she took me instead. I stood outside South Africa House waiting, while she disappeared into St Martin-in-the-Fields. I hadn’t the faintest idea what she was doing and she didn’t tell me. I used it as a key scene in my novel, The Dream Mistress. I remember it very clearly. Even so, It was a jolt to hear it being confirmed by someone else. Confirmed, but not explained.

My mother was a woman whose behaviour was often inexplicable. Living with her, day by day, was like skating on newly formed ice. It constantly shattered, every day, but there was no alternative, no other place to go.

‘I can tell you something else,’ Mrs Gold jumped in eagerly. ‘Your father rented a room in Albany Street. You didn’t know that, did you? He was a charmer. But he was a confidence man.’

Mrs Levine looked a little alarmed.

‘Doesn’t she mind?’ she asked Mrs Rosen, meaning me.

‘No,’ explained Mrs Rosen, ‘she wants to know. She said so.’

‘Well, Jimmy was a confidence man,’ Mrs Gold continued. ‘He rented this room in Albany Street – on top of the woman who made the curtains – what was her name?’

‘Anyway,’ said Mrs Gold. ‘He did a lot of confidence tricks in this place. He had money sent to him. He wrote letters out. He used the room as a postal address. And the woman became a very wealthy woman, she had a curtain place in Vivian Avenue.’

‘I had her here to estimate for curtains,’ Mrs Rosen remembered.

‘That’s right. And Jimmy was named as a co-respondent while he was living in Paramount Court.’

Whether he was named as co-respondent to the curtain woman’s divorce, or one of the women from whom he extorted money in return for romance, was not made clear. The recollections were all like this, sharp and hazy simultaneously.

I had known my father was something of a villain in a black-marketeering, womanising sort of way. I hadn’t known that he was a con artist by profession, with an office and everything. This was, if not entirely new information, a shift of emphasis.

‘Was he caught?’ I asked.

‘I remember he was in prison, for what reason I cannot tell you, but it was whispered behind your mother’s back that it was through these letters. You would have been tiny, about three. Then soon after that this tragedy happened.’ Mrs Gold was well into her stride. ‘Maybe it was before he went to prison, because he knew he was going to be caught. Or after. I don’t remember, but he came into our shop in Great Portland Street one morning and asked my husband to go horse-racing with him. I said, why does he suddenly want to go horse-racing with you, coming round out of the blue, on a working day? My husband told him he couldn’t leave the shop. Then he went to Epping Forest, but he was saved.’

‘Pardon,’I said.

‘He was found in the car in Epping Forest, with the exhaust pipe. You know?’

‘Of course, that wasn’t the only time.’ Mrs Rosen added. ‘He tried to do it again. I don’t know where.’

I remember one occasion when a policeman arrived at the flat and told my mother that my father had been found in his car with a pipe from the exhaust leading through the window. I hadn’t known he’d made a habit of it.

On an impulse I asked: ‘Did my mother try to commit suicide, ever?’

‘Not that I know of,’ said kindly Mrs Rosen, rather quickly.

‘I think she did,’ corrected Mrs Gold. ‘She did. An overdose. How old were you then? Five, I think.’

I’m washing down this family history of social crime and multiple suiciding with my second cup of tea. Still, Mrs Rosen wishes I would have another piece of cake. But I’ve got a small appetite.

‘He had a head of silver hair,’ remembered Mrs Gold. ‘He was so handsome. And charming.’

‘Absolutely charming. A perfect gentleman.’

‘He did have something about him,’ cooed Mrs Gold.

The three old ladies lost themselves in a rhapsody to the charms of my father.

‘Where did your mother find him?’ wondered Mrs Gold jarringly, a little rasp in her voice.

‘He could talk anybody into anything. He had that personality. The way be spoke, you had to listen to him.’

‘Anybody would have been taken in,’ Nathan Rosen added quietly.

‘He had personality, didn’t he? As soon as you spoke to him you felt you’d known him all your life.’

‘He was very generous. Always the first to put his hand in his pocket. You had to love him.’

‘Maybe too much,’ said Nathan, quietly again, bringing the song to an end.

After a moment Mrs Rosen asked hesitantly, lowering her voice: ‘Tell me, did he ever abuse you, your father?’

What flashed into my mind, as I considered what to say next, were those nights, many of them, when my naked mother (both my parents slept naked) would enter my room in the fifth-floor flat one door down from where I now sat taking tea, and shake me awake, telling me I had to go and sleep with my father because she wasn’t going to sleep in the same bed as him. He would put his arms around me and hold me against his hairy chest, rocking me for, I suppose, both our comforts. And pleasure. Certainly mine: I loved the feel and smell of his warm body, nuzzling into his hairy chest, squeezing myself tight up against his beating heart. I adored being held in his arms and feeling his big hands stroking me. Stroking me where? Everywhere, I think. I took in his physical affection like draughts of delicious drink. I don’t ever recall feeling anything but safe and loved in this private midnight comforting.

There was a game both my parents used to play when I was small on the occasions when they were in accord. Usually after an evening bath, I would dry myself in the living-room and then run naked between them as each, on opposite sides of the room, reached out for my vagina and tried to tickle it. When they caught me, their fingers at my vulva, I would squeal and shriek and wriggle with the equivocal agony tickling causes, and the game would go on until I was exhausted and they weak with laughter. It was my family’s way of having a good time, and there were so few good times that these occasions have a golden haze over them as I recollect them. Looking back, it’s clear to what extent I was a conduit between them, in good times and bad, a lightning rod for their excitement and their misery. But those dark nights in bed with my father felt like a private exchange between me and him. They weren’t, of course; it was just a child’s misreading of herself as the centre of the universe. I was sent to sleep with my father by my mother, and while, as a child, I supposed that they had had another argument in bed, what more likely happened was my mother’s (or my father’s) sexual refusal, and her replacement by myself. The same pattern as the living-room game.

It was only later, with the arrival of a sense of sexual privacy when I was 14, that I responded in what might now be considered an appropriate way. I had run away from my father in Banbury, and gone to my mother, who was living in a single room in Hove. On the night of my arrival, I was curled up facing away from her, when she climbed under the covers of the small bed we had to share. I wasn’t asleep, but she thought I was. She slipped a hand around my pelvis and down between my legs, and began to caress me. I was mortified.

‘Don’t do that,’ I snapped.

‘It’s all right,’ she said. ‘You’re my little girl. My baby. There’s nothing wrong with your mummy touching her little baby.’

‘Stop it,’ I shouted, terribly embarrassed, and pulled away from her. With a tut of irritation, she turned her back in a familiar sulk. I didn’t sleep that night. We argued all the next day about where I would live, and in the evening I swallowed a handful of Nembutal I found in her drawer. By the following day, I was an inmate in the Hove psychiatric hospital, and my mother and father would meet each other for the first time for years over my hospital bed, each shouting at me, ‘How could you do this to me?’ as I lay between them and pulled the covers over my head and began to scream.

‘Do you mean, did he hit me?’ I asked Mrs Rosen, cautiously.

‘Yes,’ she said, looking sympathetic. ‘I know he hit your mother. Did he ever lift his hand to you?’

‘They both smacked me sometimes. They would get into rages and slap my face, but it wasn’t a big thing. Nothing special,’ I assured her.

Warm-hearted Mrs Rosen looked genuinely relieved.

The rules. One hand for the ship applied at all times: always keep a hand free to hang onto safety rails, inside and on deck. Get to meals on time. All wet gear was to be left in the Mud Room on Deck One: no muddy boots in corridors or cabins. During landings keep within sight of an expedition leader and return to the meeting place immediately if called. Never take anything, not a stone, not a discarded feather, from any of the landing places. Do not leave anything behind on land. Comply exactly with the crew’s instructions and use the sailor’s handshake – hands to wrists – when getting on or off the Zodiacs (the black rubber motorised dinghies on which we will go ashore). We were welcome to go at any time to the bridge, but we must keep our voices down and not interfere with the work of the Russian crew on watch.

Our first stop was to be South Georgia, eight hundred miles to the south-east of Ushuaia, our starting-point at the tip of Tierra del Fuego: and there was not a thing between, only sea, sky and space. At this point on the planet you could travel its span without bumping into a single piece of land before returning to where you started. It’s the cause of the winds and storms that whip up tempests in these latitudes; there’s nothing to stop them rolling round the world picking up velocity like an ice skater. I was in no hurry to see land.

Our journey to South Georgia was almost the same length as Shackleton’s open-boat voyage from Elephant Island. I spared him a thought or two as I rocked blissfully in my bunk. A video of the surviving film taken by Frank Hurley of the Endurance expedition was shown the evening before we landed at South Georgia. Hurley’s moving pictures only got as far as the moment when the Endurance finally sank and they took off on an ice floe. Shackleton ordered the men to ditch as much as possible – he threw away the Bible apart from the fly-leaf signed by Queen Alexandra, Psalm 23 and the page from the Book of Job containing the lines:

Out of whose womb came the ice? and the hoary frost of heaven, who hath gendered it?

The waters are hid as with a stone, and the face of the deep is frozen.

Hurley’s cumbersome cinematograph didn’t last long, so there is only still photography to record his time on Elephant Island. He kept the film as best he could, but even with modern restoration it looked as ancient as papyrus. The ship beset in the ice was covered with rime, looking monumental, like a sculpture: it’s a famous picture, but the movie version of the Endurance breaking up, creaking, wailing, sometimes seeming to scream, as it buckles at the centre, the main mast crashing to the deck and the whole thing finally sinking beneath the ice, is heart-stopping. When it was clear that the ship couldn’t withstand the pressure, the dogs were dropped over the side onto a slide made out of a sail – a precursor to the emergency slide of planes. The dogs whined and barked, and slithered all out of control as the men below caught them, like fairground barkers, getting them onto the ice, where the dogs shook themselves in relief and ran rings around each other and the crew. Earlier, a scene showed the crew desperately trying to find a way through the closing ice. While some men hacked at the edges of the pack to make a split in the floe, others hauled on a rope to drag the ship through the narrow way that had been cut. The film was so frail at this point that the line of men and the rope between them seemed to bleed darkly into each other, blurring the individuals until they appeared to be umbilically attached to their own shadows. We watched a final shot of Shackleton, on his last voyage, shampooing his pet alsatian on the deck, sleeves rolled up, enjoying himself hugely. The next morning we would arrive at Grytviken, the place where, just days later, he was buried after he died of a heart attack on his next Antarctic expedition.

South Georgia’s only inhabited place, Grytviken, a whaling station from 1904 to 1965, has been preserved, after a fashion, as a museum of whaling and as the site of Shackleton’s burial. If derelict landscapes like the murkier parts of Kings Cross and the old un-reconstructed Docklands appeal, then Grytviken is a pearl of desolation. A rust-bucket ghost town, left to rot in its own beautiful way.

We were greeted by a ruddy-faced Englishman in a fisherman’s sweater and his hearty wife, though my attention was gripped by the surreal sight of three soldiers in camouflage fatigues yomping past, holding fierce-looking automatic weapons at the ready. It looked like news film of troop manoeuvres in Northern Ireland. The soldiers flashed past as it was my turn to receive a rugged handshake from the ruddy-faced man. He was the curator of the museum, the only spick and span building in town. We were warned to be careful where we walked, because floors and ceilings were likely to cave in, and not to walk towards the cluster of buildings a mile to the right, on King Edward Point, which was the British Garrison and a military secret. How many soldiers were stationed there? This was a military secret, too. ‘Very hush-hush,’ said the ruddy-faced curator solemnly.

As far as I could see South Georgia is further away from anywhere than anywhere else in the world. It’s 1100 miles from South America. The Antarctic Peninsula is just two days away from Ushuaia, while it had taken three days and nights to get here. Though – as the British Government sees it – it’s part of the Falklands Dependencies, it’s actually 1290 miles from the Falkland Islands. As a whaling station it thrived, but it’s a mystery why anyone would go to war over it once whaling was over, until you remember the oil in the surrounding waters (as well as around the Peninsula), and that the hands-off clause in the Antarctic Treaty runs out in twenty years’ time. South Georgia’s convenience for processing and distributing the liquid billions is obvious.

I walked along the shore towards the hill half a mile to the left, which sported a low white picket fence, of the sort that surrounds an English country garden. On the way, I encountered my first elephant seals, which lay dotted in small crowds and sometimes alone along the shore.

We were warned not to get closer than six feet to any of the animals we might come across, but the bulls were so still on the sand, it was sometimes impossible to spot them, and once or twice I found myself within a foot or two of a boulder that suddenly opened its eyes, raised its head, making the trunk swing obscenely, and then yawned a silent threat at me to keep my distance. Nothing is so red, moist and fleshy as the inside of the mouth of an elephant seal. With the trunk flapping above the scarlet cavern of its mouth, the story of sexual reproduction is laid bare. When the bulls do make a deliberate noise – while they’re mating and fighting – they produce from the depths of their blubbery quivering throats a cracking belch so sonorous and amplified that it echoes off the sides of the mountains.

Elephant seals being what they are, and modern travellers being what they are, the photography has begun in earnest. The debate about taking a camera with me on this trip raged for weeks. I’ve never owned a camera, never taken one on holiday. Roger-the-Ex, however, is a fervent and committed photographer. He and Chloe, and just about everyone else, insisted that I take a camera with me.

Roger brought round what he called a really simple camera. It weighed as much as a single-decker bus, had two bulky lenses which had to be screwed on and off the camera body according to the subject, and had enough scales of numbers for this and that to calculate the trajectory of the stars. I intended to be good and take it, but when I tried to practise the elementary changing of the lenses, I failed. It’s just a knack, Roger explained. I didn’t have it. When no one was looking, I hid the camera in its small padded suitcase behind the Hoover under the stairs and took off without it. My courage failed at the airport. I bought the smallest, most automatic camera that the duty free shop could sell me. It zoomed itself, adjusted itself for light and focus and wound itself on. It also fitted into my pocket. A compromise. So far I hadn’t used it.

I have a single photograph of my mother. It was taken after we had left Paramount Court, before the social workers and the University College Hospital shrinks sent me to boarding school, when she and I were living in a room in Mornington Crescent. We are in Trafalgar Square. I would have been 11. The photograph was taken by one of those professional photographers who snap tourists. My mother and I are standing shoulder to shoulder, my left, her right arm around each other’s back. Already I am as tall as her, she was barely five foot. I am, in the photo, what I was supposed to be. My hair is in plaits falling onto the front of my shoulders. The end of each plait is tied with wide ribbon into a bow. I have on a pale shirt-waister dress which falls below my knees, and a cardigan over it. I’m wearing thonged sandals so it must have been a sunny day, but for all that, my hands are covered in short white gloves. Very smart, very nice, my mother would have thought. She is in a floral frock, belted at the waist and falling almost to her ankles, as all her dresses did to hide the scar on one of her legs which was left after a road accident that happened before I was born. Her hair is dark and permed short, and she is wearing wrist-length white gloves like me. Around us pigeons are walking about, and the square is dotted with people in summer frocks and shirt sleeves. The black and white photo is faded and our faces are in shadow from the late afternoon sun behind us. My face is long and angular, hers is more rounded – now I think about it, she called it heart-shaped – but there is something sharp about her features. She is smiling directly into the camera, a posterity smile, a mother who is content to be with her daughter. My head is tipped slightly down, my chin towards my chest, and I am looking up, I now realise, with that Princess of Wales upward glance – shy or sly, hard to decide. I think there is the ghost of a smile on my face, but it’s more shadowed than my mother’s and it is a little difficult to tell. At our feet, extending along the ground and uninterrupted by pigeons, our shadows form a single elongated blot on the otherwise sunny macadam. It is a single shadow, we are standing too close for the sun to slip between our bodies. Her shadow and mine blur together into a unified shape, as umbilical as the creaky film of Shackleton’s roped-together men trying to pull the Endurance through the ice floe.

Just before this picture was taken, I had been in a local authority home for a month or six weeks, somewhere by the sea, I don’t remember where, but I recall walking in crocodile formation along cliffs with the sea to my right. I was there to give my mother a chance to get sorted out, said the social worker who took me there on the train. My mother was signed up for Social Security by the social worker and found the bedsitting room. They also persuaded her that it would be a good idea if I went to the boarding school. A progressive, co-ed, vegetarian Quaker private school which took a few problem children paid for by their local authorities who were deemed too bright to go to the authority’s schools for maladjusted children. It didn’t work out so well. My mother kept turning up at the school in Hertfordshire and screaming either at me or at the staff about them keeping me from her and about me deserting her. After a term and a half, they asked me to leave because they couldn’t deal with the disruption my mother caused. Later, at 13, when I went to live with my lost-and-found father, I went back to the school. That didn’t work out so well, either. I was expelled, this time on my own account, for general waywardness, after eighteen months. Thereafter to Banbury to my father, then off to my mother, then into the hospital in Hove.

None of this is evident in the photo of my mother and me in Trafalgar Square on a sunny day, except perhaps in the shadows on our faces, but that, of course, is nothing more than a retrospective conceit.

‘What more do you want to know?’ asked Mrs Rosen when I phoned her a couple of weeks later and asked if I could see her again. ‘We kept ourselves to ourselves. We don’t know much.’ It wasn’t unkindly said, only defensive. I should have let it go, but I’d got home after the first meeting with them and spent several days in bed brooding. Not so much thinking about it, as shaken, as I hadn’t expected to be, by the reality of my past in the reflection of their memories.

I knew that my parents were histrionic, but the slant on my father – not just a bit of a rogue, not just a bastard as my mother said, but a professional con man, not just a bad husband and womaniser, but as inclined to suicide attempts as my mother – gave me a fright. Between nature and nurture, it looked quite grim. I’ve been, for some time, as I put it to myself, all right. But how all right could I be, genetically and psychologically, with parents like that? I came from a family of suicidal hysterics. I’d been suicidal and hysterical in my time, then taken stock and made a decision, or just grown out of it, but now I felt, as I walked back to the car, that I might not have the choice of being anything else; that for years I had been deluding myself into the notion that I had a choice. What sent me to bed was the thought – no, the conviction – that I was the sum of those two people, that under the pretence of an achieved balance, more or less, I hadn’t got a hope in hell of being other than what they were. I felt myself to have been all along skating over the thinnest sliver of ice; believing that it was solid when it was only ever a brittle and probably diminishing floe.

My father’s emotional vulnerability was far more concealed, at least from me, than my mother’s. When I was still very small, he was as beguiling to me as he had been to the ladies of Paramount Court. I adored him; he adored me. At weekends the two of us would roam London, take possession of it. Saturday mornings watching the Changing of the Guard, patting the horses standing guard in the street, my father egged me on to try to make the guardsmen laugh. In the afternoon, we would explore the museums; the British Museum, or the museums in Exhibition Road, roaming the Natural History, Geology and Science Museums, while he made up stories about the exhibits, ad-lib comedies that split my sides with laughter. What a talker, such a charmer, the old women had said, sighing. Sunday mornings at Petticoat Lane, buying pickled cucumbers, bagels and cream cheese, and then, after a Chinese lunch in Soho, an afternoon spent at the cinema, first at the news and cartoon house in the Charing Cross Road, and then to Leicester Square for a proper film, in the dark, the long tunnel of dusty light over our heads, his arm around me, my head against his shoulder.

I knew he loved me, and even after he had left the last of several times without making contact with me, I knew he had loved me. Now, after visiting the old women, there was a new thought: I had been charmed by a man who made his living charming women. I saw myself suddenly as another of his conquests. Anybody would be taken in ... You had to love him, the old people had said. This was a radical change of perspective; a brand new loss. My father practising his skills on me. Some people cannot help but make people love them.

The first time I remember him leaving, I was about six or seven. ‘He’s gone, he’s left,’ my mother said. There’s no way to convey the flatness, the despair in her words. You’ve heard it from time to time in the movie tones of Marlene Dietrich or Bette Davis. It was late, I’d been in bed for some time. I pretended to be asleep when she walked into the dark room and told me. I didn’t know what to say, and I was frightened by what would happen to the voice if it was encouraged to go on. Besides, I had a despair of my own. He’d gone, he’d left.

It may have been the next day, or perhaps several days or weeks later, I can’t remember, but I came home from school to find the bedroom door shut. My mother was often in bed.

I opened the door to a daylight-darkened room, the curtains closed, lights off, an artificial dusk. There was a noise, a moaning, a weird wailing and I saw my mother lying in bed. She was naked, but she always slept naked. Only she wasn’t asleep. She was rolling frantically from side to side in the bed, the covers in turmoil, like someone with a high-grade fever. Spittle dribbled from the corners of her mouth. All the while she was rambling. Talking to God, complaining about her life, crying ‘Help me, help me,’ muttering maledictions.

I called ‘Mummy’ from the doorway, reluctant to go nearer, but she didn’t answer, or notice that I was in the room, so I had to go closer to the bed.

‘What’s the matter?’ I asked her, touching her clammy skin.

She flinched and stared wildly at me. A crazy woman.

‘Don’t you touch me,’ she screamed. ‘Who are you? Get out. I don’t know you.’

What I remember is feeling nothing, just turning sharply to leave the flat, and business-like, ringing the bell on the door opposite. We didn’t know them, but a woman answered the door and I said, politely: ‘My mother’s ill, can you help, please?’ A very practical kid. A bit of a cold fish, she must have thought when she entered the bedroom and found my mad mother writhing and keening in delirium.

They carried her off on a stretcher and someone in the flats, not Mrs Gold, Rosen or Levine, sent me to stay with a relative of theirs. Then I went to live with a family who I’d never met before, who it only lately occurred to me was a foster family, but who I was told were ‘cousins’. Then my father turned up. Out of the blue as far as I was concerned. He took me back to the flat in Paramount Court on that first visit, sat me on a dining chair and positioned himself on the floor in front of me, on his knees. He wept – this was the only time I saw his vulnerability and I hated it – begged my forgiveness, and made a solemn and formal promise through the tears (they dripped off the end of his nose to my exquisite embarrassment) that he would never, never leave me again. Then we went back to the tenement flats – he couldn’t look after me himself yet, he told me.

After that he came once a week and we went, not to Petticoat Lane, Exhibition Road or Leicester Square, but to visit my mother in the hospital. There was a lengthy bus ride and then what seemed a very long walk along a tree-lined suburban road. Invariably, during this walk I needed to pee, so each week we would knock at a different house and ask if I could use the bathroom. It became a game, a kind of roulette. I discovered all manner of different toilets, and best of all, one with a musical toilet roll. We were never refused, and sometimes we ended up having a cup of tea with the householders. The charming father and his young daughter were given tea and biscuits by extraordinarily kind and trusting people who, while I was on the loo, were doubtless told of our visit to the ailing wife and mother in the mental hospital up the road. I suppose they thought it was a shame, and such a nice man, poor child. Those brief visits were adventures into unknown worlds, to people whose houses and lives looked to me so solid and stable. Settled houses for real families with chintzy covered furniture that had the quality of eternity about it, and silver-plated teapots waiting in glass cupboards and brought out for visitors. Other lives. But frozen by a single visit into comfortable certainty. It was like going to the movies, too, and slipping through the light beams into the lives on the screen.

Until, of course, the reason for our being there could be put off no longer, and, for me, the price of being with my father had to be paid for by seeing my mother. She wasn’t dramatically mad any more; she was a shell now, an emptiness, either drugged or semi-catatonic, or both, which passively received our bunch of flowers from the nurse, who took them from my hand and made approving noises as she placed them on my mother’s lap, where they lay pointlessly until the nurse more practically went off with them to find a vase.

It seemed, however, that only with my mother’s recovery was I going to get my father back. We would ‘all live together again’, my father assured me, when my mother got better. And it would be different, he said, there wouldn’t be the terrible rows, and he would never leave me again. I’m sure it was put in terms of leaving me, and not my mother.

It took a while, but eventually she started to know who we were and managed a limp smile when we arrived. Soon there were stiff little visits to a back room in a local tea shop, and an occasion when both my mother and my father came and had tea with me at the foster woman’s house. When we all went to live back in the flat, it was explained to me that Mummy was very fragile and I must be very careful about what I said. In fact, I always had been, but now the surface of the world itself had turned to delicate ice and we all tiptoed over it, my mother, too, pretending that everything was all right. Within a few months things returned to normal.

My father took me by the shoulders one day when I was almost eleven and almost finished at primary school. He told me that he was leaving for good. ‘This time, I’m never coming back. Do you want to come with me, or stay with Mummy?’ I have no idea why, except I didn’t know where he was going, but I said hardly without a pause that I would stay with her. The decision remains a mystery, but I suppose it’s reaching to call it a decision. It was more like a nervous reaction to a sudden announcement that life was going to change again, and to the nonsensical requirement that I state my preference there and then for good and all. His bags were already packed and in the hallway. My preference had always been for my father. I chose to stay with my mother and watched him disappear through the door with his suitcase. I don’t know why.

Waiting again. For weeks we lived in the empty flat, while my mother sat helplessly in the armchair the bailiffs had left, telling me that when they finally came and threw us out we would go and live on the street – under the arches of Charing Cross, to be precise. We would practise, as she dragged me by the arm and whisked us out of the flat as if we were never going to return. ‘What’s the point of waiting to be thrown out? Now, we’re on the streets.’ And we’d walk around as if there was nowhere to go, as indeed, there soon wouldn’t be, in the rain. I remember it as always raining on these occasions. Probably it wasn’t always raining.

This time I couldn’t stand the uncertainty. I had just started at grammar school, and went every day as if nothing unusual was happening. ‘Don’t say anything to anyone,’ my mother instructed. ‘If anyone asks about your father, say he’s dead.’ I did as I was told. Better a dead father than to admit to desertion. I wondered how I was going to manage going to school when we were living under the arches. I failed, repeatedly, to arrive at maths lessons with a geometry set. The cost was out of the question. I didn’t even mention it to my mother. But every day at the beginning of maths, I had to stand up and confess that I still didn’t have a geometry set. It became a class joke, whipped up by the archetypal sarcasm of the maths mistress. One morning, instead of leaving the flat and going to school, I lay down on the floorboards and started to scream. Two weeks later the social workers arrived, alerted to my non-attendance at school. I’d short-circuited the waiting.

‘What more do you want to know?’ asked Mrs Rosen, at the beginning of my second visit to Paramount Court.

I wanted to know what I had forgotten to ask about the first time.

‘I wonder how you remember me as a child.’

‘As a child,’ she told me, ‘you were very bright. You were the youngest of all our kids. You were the baby. But you were up to it. You were the cleverest. What they did, you could do, maybe better. You could talk! You could argue! You kept up with them. You could stand up to the others. You always knew how to stand up for yourself.’

There was a real atavistic, mother and child moment of satisfaction for me when Mrs Rosen offered me four-year-old Jennifer standing up for herself. It passed, but still the picture of obdurate, unputdownable Jennifer aged four pleased me. It also chimed with other memories of my childhood. Mostly, they were memories of being in trouble, of refusing to back down, of demanding my rights. There was a tough child, right from the start, with a sense of herself: a survivor, to put against the flaky genes and the training in hopelessness. I suppose, with the threat of my live or dead mother suddenly coming back into my life, I had gone to Mrs Rosen to find out just that. To check that there had once been and always was that survivor. And Mrs Rosen, inadvertently or not, gave her to me in an unexpected moment of good mothering.

The white picket fence surrounded Grytviken’s graveyard, where past whalers were buried under neat white low headstones. I had climbed the hill to see Shackleton’s grave, and it was immediately obvious, with its tall hewn granite post and ‘Ernest Henry Shackleton, Explorer’ carved on it and fresh alpine flowers at its foot. But another grave caught my eye, at right angles to Shackleton. It had a low white headstone, but unlike the rest had a rough wooden cross standing over it. It too had fresh pink flowers and was the only other grave to have been regularly and carefully tended. The words burned into the wooden cross read:

RIP

FELIX 26.04.82 ARTUSO

Beneath the horizontal under the RIP there was a small painted rectangle made of a single white stripe sandwiched between two pale blue ones.

At the museum building, two soldiers sat on the steps leading up to the doorway. I said hello as I passed.

‘You’re English,’ one of them declared, as a shipwrecked British traveller might greet his rescuer.

He was in his mid-twenties and his name was Andy (his friend’s name was Scot, which I was to remember is spelt with one t).

I asked why they were patrolling with guns.

‘Making sure they can be seen,’ Andy told me.

‘By whom?’

‘The Argies. There’s been a rumour going round that the troops here don’t have any guns, so we’ve been making them visible.’

I looked around at the bay, which was deserted apart from the two half-sunken whalers and our white ship waiting for our return.

‘Who’s looking?’

‘Spies on the ships. We’ve got to let them know not to mess with us.’

I asked Andy about Felix Artuso, up on the hill. He reminded me that South Georgia had been taken by a small group of Argentinian soldiers posing as scrap-metal merchants. Fourteen marines went into hiding and then fought them off. Fifteen Argentinians were killed, according to Andy, though the official number was three. Young Felix Artuso was one of them. A marine came face to face with him and, thinking he was going for a gun, shot first. It turned out that Felix was unarmed.

‘It’s what happens in war,’ said Andy sorrowfully, speaking very respectfully of Artuso, like a fallen comrade. ‘His parents wanted him to be buried on South Georgia. The Brits buried him with full military honours. It’s the way we do things.’

Since the war, three soldiers had died on South Georgia. One saved his two-can allowances of beer for a Friday piss-up and thought he could swim across the bay. He froze to death in about seven minutes. Another also got drunk and fell during an inadvisable walk in the middle of the night, dying of exposure. An Irish Ranger died from cold and injuries while trying to climb one of the mountains on his own.

‘The boredom gets to you,’ explains Andy. ‘It was really nice to talk to someone from home.’

In the museum I got three copies of a postcard of Shackleton, his hair parted in the middle and slicked down, looking uncomfortable in front of the camera, but wonderfully handsome in a rugged way. He looked as roguish as he seems to have been. A bit of a con man, who took off on the Endurance expedition before the money was actually available, leaving others to sort out the mess. Something of a ladies’ man, he was, in his charming Irish way. Brother Frank went the whole way and was actually imprisoned for some financial shenanigans with the English aristocracy.

It was beginning to rain, and the sky was darkening. The glorious sunshine instantly became a thing of the past. I began to see that things might be surprisingly changeable around these parts. As the wind got up, suddenly Grytviken was a dour, deserted place. For the first time I started to feel cold and damp. It happened from one moment to the next. A small shiver of bleakness that was not entirely related to the weather ran through me. I felt quite happy to get into one of the first returning Zodiacs and head back for Cabin 532. My first landing hadn’t been either white or solitary.

By the afternoon, the world had turned industrial grey. While we were having lunch, the ship sailed a short distance south, lurching through a disturbed sea, down to St Andrew’s Bay for our second scheduled landing. St Andrew’s Bay was the great penguin treat of the trip. We were warned that the landing would be cut short if the wind got any worse. It took about fifteen minutes to get to the shore as the dinghy tacked and swerved to avoid the worst of the head-on wind. It was, however, the most exhilarating ride I’ve ever had, fast and furious, the motor buzzing angrily against a wind that howled past my ears and made my eyes water salt tears to match the salt spray covering my face. We were so close to it, intimate now with the movement of the waves, the weather, the Antarctic sea. When not lying on my bunk or staring out from the bridge, I’d choose this. From time to time when we smacked into a big wave, I laughed out loud.

As we approached the slightly protected Bay, the wind let up a little and it was possible to look up, straight ahead towards the land. We were being watched. The long shoreline and the beach right back to the glacier and mountains were packed so tight with penguins that they formed a continuous carpet. A legion of black faces and orange beaks pointed out to sea facing in our direction, seeming to observe our arrival. One day, once a year or so, black rubber dinghies approach, and a handful of people come to the Bay, believing that the penguins are watching them arrive. For the penguins, it’s just another day of standing and staring. They parted slightly to make way for us, but they still stood looking out to sea. We were not part of their existence, presented no obvious danger and therefore were ignored, quite overlooked. If you stood in their way as they waddled along their track from nest to sea to feed, they stopped a few inches from your feet and made a small, semi-circular detour around you, as they would if they found a boulder in their way. If you got down on your knees and faced them eyeball to eyeball, they looked back, turning an eye towards you, but deciding what you were not, lost interest rapidly.

I was very taken with this timeless standing, unwitnessed, unwitnessing, that we were interrupting, though only barely. That was the point, for me, of Antarctica; that it was simply there, always had been, always would be, with great tracts of the continent unseen, unwitnessed, cycling though its two seasons, the ice rolling slowly from the centre to the edges, where eventually it breaks off.

The weather had worsened. It was now dark, as if dusk had fallen, a twilight that in this Antarctic summer does not occur. After fifteen or twenty minutes’ walking along the beach, the wet and icy blasts began to seep through the layers as if they were merely gauze. When it reached the flesh, I felt I had an inkling of what it means to be cold, but then it went deeper, and after half an hour it had gone beyond the skin and directly into the bones. My very marrow was chilled, I felt iced and saturated from head to foot. It was as if the wind, having got my measure, was denying my existence and simply rattling through me. I have never felt so unprotected in my life as in that bleak, dark landscape where there is absolutely nowhere to shelter. Only in those dreams where you find yourself walking naked down a busy street, have I felt as vulnerable.

The next morning around 6.15, I lay shivery in my bunk with a sore throat. I had a streaming, screaming head cold and felt ghastly. I had woken at four to the unrelenting daylight feeling a bit dispirited, a small damp weight inside of me. A tiny blueness. When I thought about it, perhaps it was a moment of panic at being out of reach of anywhere, hundreds of miles out of sight of land. Now I got my achey self up to look out of the window. The sky was dove grey with heavy snow-laden cloud, and the snow was falling softly, making the windswept wilderness of the Antarctic sea as silent as any suburban winter garden. The horizon was a very long way away. I skipped breakfast and both of the day’s lectures designed to help fill our at-sea time, devoting the day to my cold, my bunk, my book and the view from my window. Sleeping, reading and staring out at the snow and sea. I could have done this for ever. No Sister Winniki to nag. Just left alone to take all the pleasure I wanted in indolence. What more could anyone want?

And then in the evening the first iceberg floated by my window.

The iceberg emerged before my lazy gaze like a mirage, a dream appearance, a matt white edifice ghostly in the misty grey light and falling snow. A sudden, smoothly gliding event in the great empty sea under the great empty sky. I blinked at it There was none of the disappointing familiarity of something seen too often on TV or in picture books. This startled with its brand new reality, with its quality of not-like-anything-else. Even the birds seemed to have hushed for our entrance into the land of ice. The tannoy squawked into life, and Butch, our leader (well, no, he wasn’t really called that, but he’ll always be Butch to me), announced: ‘Ladies and Gentlemen, we have icebergs.’

Time to get up. I pulled on a track suit and headed up to the bridge, where I discovered that, like a momentous theatrical production, we were proceeding into real Antarctica through a corridor of icebergs. As far as the eye could see, to either side of us, icebergs lined our route. We’d arrived in iceberg alley. It was absurdly symmetrical, like a boulevard in space. The bergs were tabular, exactly as described, flat as a table on top, as if someone had planed away their peaks, too smooth to be real, too real to be true. It took about an hour before we had sailed through iceberg alley, and all the time we stood and watched in silence.

The icebergs close-up, even quite far away, were not daydream white at all. Blue. Icebergs are blue. At their bluest, they are the colour of David Hockney swimming pools, Californian blue, neon blue, Daz blue-whiteness blue, sometimes even indigo. They were deepest blue at sea level, and where cracks and crevices gave a view of the inside of the berg, where the ice was the oldest and so compacted that all the air had been forced out.