Among other certain things (death, taxes etc) is the rule that no work of science fiction will ever win the Booker Prize – not even the joke 1890s version. H.G. Wells’s The Time Machine had no chance against ‘literary’ authors like Hardy and Conrad. In the twenty-five years it has been running, no SF title, as I recall, has even been shortlisted for Martyn Goff’s real thing. In 1940, T.S. Eliot struck the recurrent establishment note when he labelled Wells a ‘popular entertainer’.(Dickens was stigmatised with the same term by F.R. Leavis in The Great Tradition.) Patrick Parrinder has been opposing such anti-Wellsian prejudice for the best part of a quarter of a century. His opposition takes the form of scholarly works which patiently mount the case for critical respect. Parrinder’s contributions include the Critical Heritage volume (1972), a study of Wells’s composition methods, H.G. Wells under Revision (1990, co-edited with Christopher Rolfe), and the reissue of Wells’s scientific romances currently appearing under the World’s Classics imprint. (For copyright reasons – Wells having died in 1946 – this series will probably only be available in America.) Parrinder’s more theoretical interventions include Science Fiction, Its Criticism and Teaching (1980), a work which places Wells as ‘the pivotal figure in the evolution of the scientific romance into modern science fiction’.

Shadows of the Future (a title which plays with the equivocal initials ‘SF’) is Parrinder’s most forceful critical plea so far for the importance of Wells. He begins by staking a claim for The Time Machine as ‘one of the Prophetic Books of the 19th century’, a work which ‘casts its own shadow over futurity’. In fact, two claims are made: one for Wells as a prophet novelist, the other for prophetic fiction (PF?) as a significant literary genre. Parrinder’s own discursive method, as he tells us, is modelled on the Time Traveller’s – a series of ever further ranging intellectual explorations. Wells is praised as the Edward Gibbon of his day, and he is also celebrated for writing parodic fiction of Bakhtinian subtlety whose designs are indistinguishable from the current hypotheses of theoretical physicists like Kip Thorne and Stephen Hawking. Parrinder’s chapters take the form of free-wheeling meditations on Wellsian topoi – ‘Possibilities of Space and Time’, ‘The Fall of Empires’, ‘Utopia and Meta-Utopia’. In Part Two of Shadows of the Future, he branches out into ‘Wells’s Legacy’ – which he takes to be the whole corpus of 20th-century British and American science fiction. There is a wealth of massively informed insight in the book, but more impressive – and more convincing – is the high seriousness with which Parrinder approaches his subject.

There are, however, three problems in joining Parrinder on his high critical road to a full rehabilitation of Wells. The first is Parrinder’s advocacy of the early scientific romances (the only works by Wells which have currency nowadays) as ‘prophecy’. A prophet wanting to communicate his forecasts to mankind might engrave them on stone tablets; he might buy billboard space in Leicester Square or an advertisement on Sky Television; the last thing he would do would be to wrap his prophecies up in popular science fiction – a genre which ranks in cultural authority with the fortune cookie and the cracker motto. A second problem is SF’s appalling record in accurately predicting scientific discoveries and future events. After the usual genuflections (‘Wells foresaw the future wars and anticipated the weapons of war, notably the aeroplane, the tank and the atomic bomb’) any comparison of, say, The War in the Air with what actually happened aeronautically in the world wars, or The First Men in the Moon with Cape Canaveral in 1969, reveals how wildly wrong science fiction invariably is. Nostradamus, Old Moore and Mystic Meg have SF beat every time. (Parrinder sportingly quotes against himself Fredric Jameson’s paradox that science fiction’s role in life is ‘to demonstrate and to dramatise our incapacity to imagine the future’.) The third, and most intractable, problem is the non-fiction prophecy which Wells wrote in the early 20th century, during the period when he felt he was outgrowing scientific romance, and put novels like The Time Machine away as childish things. It is an embarrassment for Wellsians that the master should so disvalue what his admirers, and posterity generally, have seen as his masterwork.

The status of Wells’s non-fiction prophetic books has recently been called into question in a way which has largely confounded Michael Foot’s purpose in writing The History of Mr Wells. It is clear that Foot first conceived his biography as a celebration of Wells’s socialism – more particularly his ‘libertarian’ socialism, which Foot takes to be healthier than the ‘bureaucratic’ brand of the doctrine, associated with the narrow-gutted Webbs. The History of Mr Wells aims to recover ‘HG’ (as Foot matily calls him) as an English socialist hero. The trouble started in 1992, with the publication (trailed by an incendiary article in the Sunday Times) of Michael Coren’s The Invisible Man: The Life and Liberties of H.G. Wells. Coren states his thesis with disarming straightforwardness: ‘H.G. Wells was a racist, an anti-semite, a plagiarist, a crass exploiter of women, and a social engineer of manic proportions.’ These offences, according to Coren, have been airbrushed from the record by Wells’s admirers.

Coren’s most powerful ammunition is found in Anticipations (1901), the first of H.G. Wells’s non-fictional prophetic manifestos on the subject of the utopian world state of the future. In this work Wells refers in passing to the Jew’s ‘incurable tendency to social parasitism’. He goes on to ask: ‘how will the New Republic treat the inferior races? How will it deal with the black? How will it deal with the yellow man? How will it deal with that alleged termite of the civilised world, the Jew?’ No clear answer is forthcoming. Malcolm Muggeridge, whom Coren enterprisingly interviewed, muses whether ‘Wells had read some of the works of the Anglo-German race theorist, proto-Nazi and anti-semite, Houston Stewart Chamberlain ... he opted for schemes that make us shudder today.’ At the same time as Coren’s assault, John Carey in The Intellectuals and the Masses branded Wells an inveterate despiser of the common man. All in all, 1992 was a bad year for the Wellsian cause.

Coren’s book was dealt with in this paper by Patrick Parrinder (8 April 1993). Parenthetically squelching Coren’s ‘mediocre scholarship, factual howlers and slipshod style’, Parrinder approached the question of the anti-semitism in Anticipations through a discussion of the spirit of the age:

The Boer War had started with the usual catalogue of military disasters, which to Wells (and many others) reflected the inefficiency of the British Establishment. ‘Efficiency’ was one of the buzzwords of Anticipations, which culminated with the argument that the world’s peoples would be tested against the ‘new needs of efficiency’ and that some were destined to fail and disappear. The concept of efficiency was double-edged. In his first attempt at futurology Wells saw efficiency as military rather than economic, and as racial or biological rather than military. Greater efficiency entailed measures of selective breeding, including enforced abortion and infanticide.

Parrinder grants that in Anticipations Wells was apparently willing to countenance the elimination (but not genocide) of the ‘swarms of black and brown’ in the same name of ‘efficiency’. He concedes that Wells ‘equivocated embarrassingly about the Jews’, but then anti-semitism was part of the eugenic philosophy which the writer had picked up second-hand from Francis Galton and Karl Pearson, whose public lectures the Fabians were attending in the early 1900s and who, as Parrinder notes, ‘campaigned for eugenic legislation not unlike that in the Third Reich’.

It is a crucial point in Parrinder’s line of argument that Wells almost immediately ‘began to doubt the scientific claims of Galton and Pearson. In 1903 he outspokenly condemned eugenic measures as wholly impractical.’ By the time of A Modern Utopia (1905), Wells had wholly mended his views. ‘In fact,’ Parrinder claims, ‘very soon after Anticipations, Wells took steps to expunge both tendencies’ – racism and eugenics – ‘from his thought. Eugenic legislation does remain in force in A Modern Utopia, guided (we must suppose) by an accurate science of genetics far in advance of the knowledge available to the Victorians and Edwardians. But Wells adds that “there would be no killing, no lethal chambers.” ’

Parrinder elaborates on this claim in Shadows of the Future, where he describes the social blueprint contained in A Modern Utopia as ‘a money economy, an advanced technology, a humane penal system, regulated marriage, population planning, sanitation, health-care, state-supported child-care, central data storage, institutionalised wage-bargaining, and a post-Christian synthetic religion’. (Note ‘a humane penal system’.) Largely forgotten though it is now, A Modern Utopia was, at the time, the most influential book Wells had written. As Vincent Brome recalled, it was ‘widely read by university students’ and observably affected their moral behaviour – particularly in its Fabian advocacy of free love. Other seeds may also have been planted by the work, in Britain and in Europe.

Michael Foot is in sympathy with Patrick Parrinder’s reading of this crucial phase of Wells’s intellectual evolution. Their discourses, however, are markedly different. Foot’s style is oratorical. His mode of argument is to load those critics with whom he agrees with superlatives, and pooh-pooh the opposition – a technique which might be effective in the debating hall, but deflates disastrously on the page. The platform address works best with the charge of misogyny. Foot’s robust contention that Wells could simultaneously and honestly love his wife and his young mistress Rebecca West (as well as any number of other young mistresses) is more palatable than Coren’s moralistic posturings about infidelity. And there are also things which Michael Foot chooses not to know. He wholly ignores, for instance, the Hedwig Grattingen affair, in which one of Wells’s chucked mistresses (at a period when he was concurrently being ‘faithful’ to his wife Jane and to Rebecca) broke into his London flat and slashed her wrists. The implication of Foot’s reticence – that there is no need to repeat such things, since they are already well enough known – carries moral weight. He is similarly convincing in his blank and furious denial that Wells’s final mistress, Moura Budberg, could have been a KGB agent.

Foot is on trickier ground with Coren’s charges that Wells was a ‘racist’ and ‘ruthless eugenicist’. In the body of The History of Mr Wells, Foot brushes these allegations away with the occasional contemptuous flourish. ‘No fair-minded person could brand the writer of Anticipations a racist.’ The charge of racism is ‘incredible’ and ‘absurd’. But a more serious attempt is made to engage with Coren (and, in sorrow rather than in anger, with Carey) in the footnotes. A particularly huge appendage is written to answer Coren’s principal objections to Anticipations. According to Foot, the central issue for Wells was ‘the ever-increasing world population’. His concerns were grandly and abstractly demographic:

He had set out his views in Anticipations and in several other of his early publications ... Several other writers of the period described the problem in similar if not such graphic terms as HG employed, but when he saw that some critics were interpreting what he had written in Anticipations in what might be called racist terms – despite his specific disavowal – he look precautions in his A Modern Utopia to try to ensure that he would guard against any such misplaced and even malicious misinterpretation.

There follows an extended résumé of Parrinder’s ‘brilliant’ review of Coren in the LRB.

This is an extraordinarily touchy subject, and to make any headway one needs to distinguish carefully (as Foot does not) between eugenics and racism. It is also necessary to distinguish between programmes conceived as long-term measures to keep population in check (immigration and birth control, for instance) and short-term penal measures devised for social hygiene. It is incontrovertible that Anticipations was racist in some of its central formulations. This is clearer if one gives the whole passage from which Parrinder quotes in part: ‘And for the rest – those swarms of black and brown and yellow people who do not come into the needs of efficiency? Well, the world is not a charitable institution, and I take it they will have to go. The whole tenor and meaning of the world, as I see it, is that they have to go.’

On the question of racial prejudice, A Modern Utopia certainly bears out Parrinder’s and Foot’s contention that within a few years, Wells had drastically changed his tune. Most of the chapter ‘Race in Utopia’ could be quoted by Martin Luther King without embarrassment. There are no ‘inferior races’, Wells now asserts. Nor is there any physiological basis for racial discrimination. ‘Even the Jews’, he observes, have more physical differences within their ethnic group than there are between them and their host societies. In response to a racist interlocutor (evidently Sidney Webb) Wells’s narrator complacently foresees ‘all the buff and yellow peoples intermingling pretty freely’ – even ‘Chinamen and white women’. It is evident that two factors had intervened to change Wells’s thinking on race between 1900 and 1904–5. One was the odious Alien Immigration Act, foisted on Balfour by Tory extremists in 1905. The other was the sickening racism of Wells’s fellow Fabians – a group with whom he was increasingly at odds. Sidney Webb, for instance, in a 1907 pamphlet (‘The Decline in the Birth Rate’) declared:

In Great Britain at this moment, when half, or perhaps two-thirds of all the married people are regulating their families, children are being freely born to the Irish Roman Catholics and the Polish, Russian, and German Jews, on the one hand, and to the thriftless and irresponsible – largely the casual labourers and other denizens of the one-roomed tenements of our great cities – on the other ... This can hardly result in anything but national deterioration; or, as an alternative, in this country gradually falling to the Irish and the Jews. Finally, there are signs that even these races are becoming influenced. The ultimate future of these islands may be to the Chinese!

Wells’s ‘so what’ is very refreshing. His thinking on the domestic applications of eugenics is less appealing and tends, if anything, to be even harsher than Webb’s. In Chapter Five of A Modern Utopia, ‘Failure in a Modern Utopia’, Wells ponders what his ideal state of the future should do with the unfit, undesirables and the criminal classes. It is accepted that Utopia will always have a proportion of dull citizens: given the roll of the genetic dice, some low IQs must always come up. The dull must be discouraged from breeding in favour of the ‘better sort of people’, but mildly coercive measures will suffice. Over the long term, selective breeding will mean fewer dull Utopians, but complete eradication will be impossible. They are the irreducible sludge at the bottom of the gene pool. A more soluble problem is posed by ‘idiots and lunatics ... people of weak character who become drunkards, drug-takers and the like ... persons tainted with certain foul and transmissible diseases ... violent people and those who will not respect the property of others, thieves and cheats’. These undesirables require ‘social surgery’. In elaborating what this means, Wells anticipates Michael Howard’s ‘three strikes’doctrine:

So soon as their nature is confirmed, they must pass out of the free life of our ordered world. So soon as there can be no doubt of the disease or baseness of the individual, so soon as the insanity or other disease is assured, or the crime repeated a third time, or the drunkenness or misdemeanour past its seventh occasion (let us say), so soon must he or she pass out of the common ways of men.

What ‘passing out’ means is sterilisation (‘The State will, of course, secure itself against any children from these people’) and quarantined ‘seclusion’ for life on islands, patrolled by gunboats.

If castration and the concentration camp for alcoholics, junkies, trollops and luckless fellows with a dose of the clap represents a ‘humane penal policy’, Draco himself would have difficulty in coming up with penalties that Patrick Parrinder would think severe. And if this represents ‘libertarian socialism’, thank God Michael Foot never became prime minister: half of us would be walking around without our testicles. Of course, it will be argued that Wells is merely engaging in Shavian shock tactics: in ‘real life’ he would never advocate anything as disgusting. But the fact that, if anything, Wells was more savage in his private thinking than he dared be in print is proved by a passage in a book which Wellsians seem to have neglected, Daniel Kevles’s In the Name of Eugenics (1985). Discussing attitudes to mass forcible sterilisation in the early 1900s, Kevles records:

In the United States, a strong consensus in favor of sterilisation – supporters ranged from Margaret Sanger [with whom Wells later had an affair] to Theodore Roosevelt [one of Wells’s American admirers] – grew among eugenicists. In Britain, no such consensus existed. Comparatively few British eugenicists were convinced of the necessity for the procedure, although among those who considered it were Francis Galton (‘except by sterilisation I cannot yet see any way of checking the produce of the unfit who are allowed their liberty and are below the reach of moral control’) and H.G. Wells, who pondered improving the human stock by ‘the sterilisation of failures’.

Kevles is drawing here on Wells’s hand written notes to one of Galton’s discussion papers, currently in the Galton archive at UCL (file 138/9). The date is 1904, and the full text of Wells’s comment is: ‘The way of Nature has always been to slay the hindmost, and there is still no other way, unless we can prevent those who would become the hindmost being born. It is in the sterilisation of failures and not in the selection of successes for breeding that the possibility of the improvement of the human stock lies.’

If there is a smoking gun in Wellsian scholarship, this chilling marginal observation – designed for no eyes other than Galton’s – is surely it. The either/or reasoning is stark. Either you kill (the ‘natural’ way) or you forcibly sterilise (the artificial way). Either you take these options, or the race fails. ‘Humane’ options do not exist. There is no evidence here of the recantation which Parrinder and Foot would have us believe intervened between Anticipations and A Modern Utopia. If anything, in 1904, Wells was thinking even nastier things than he had been in 1900.

Wells was not, as Michael Foot suggests, on the soft wing of the eugenics movement in 1900-5, he was in the minority on the ultra-hard wing. In the crucial years between 1900 and 1905 his views on eugenic purity and the means of achieving it did not soften, although he certainly grew more liberal on questions of race and immigration. Publicly, in A Modern Utopia, he advocated concentration camps and sterilisation for undesirables. Privately, he advocated (Kevles’s ‘pondered’ is too generous) solutions of a more final kind. Of course, other things being equal, Wells preferred the humane castrating shears to the inhumane gas chamber, but one or the other it had to be. Of course, as the decades passed, Wells moved from allegiance to negative eugenics (sterilisation of the unfit) to positive eugenics (rational marriage, contraception). Of course, as Parrinder and Foot are at pains to point out, he was an early critic of Mussolini. Traces of anti-semitism can be found peppering his work to the end; but,on the whole, he seems to have purged most of it from his system after 1900. Of course, a stray ‘Ich habe es nicht gewollt’ case can be made for Wells. It is possible that if he had lived to witness it, he – like his fellow Fabian Shaw – might have disbelieved the evidence of what the Nazis did.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

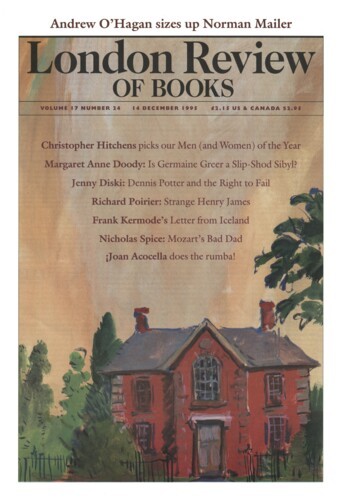

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.