For the patient in psychoanalysis the most disabling insights are the ones he cannot forget; and for the psychoanalyst, by the same token, the most misleading theories are the ones he cannot do without. Mental addictions, that is to say, are supposed by psychoanalysis to be the problem not the solution. People come for psychoanalysis when there is something they cannot forget, something they cannot stop telling themselves about their lives. And these dismaying repetitions – this unconscious limiting or coercion of the repertoire of lives and life-stories – create the illusion of time having stopped. In our repetitions we seem to be staying away from the future, keeping it at bay. What are called symptoms are these (failed) attempts at closure, at calling a halt to something. Like provisional deaths, they are spurious forms of mastery.

The paradox of living in passing time and craving durable truths (or symptoms) as the best equipment for this predicament has traditionally been the province of Western metaphysics. But the practice of psychoanalysis, like the practice of ordinary life, raises ‘philosophical’ questions in rather immediate form. How long is something true for, and why should duration over time be a criterion for the validity of a so-called insight in psychoanalysis, or anywhere else? After all, the repetitions from which the patient is suffering, and which for psychoanalysis define the realm of pathology, are extremely durable, unlike the ‘insights’ used to explain them. For Freud these repetitions are the consequences of a failure to remember. Psychoanalysis, as Malcolm Bowie writes, ‘is overwhelmingly concerned with the production and transformation of meaning’. Whatever cannot be transformed, psychically processed, reiterates itself. A trauma is whatever there is in a person’s experience that resists useful redescription. There is no future in repetition.

But if, as Freud says, we repeat only what we cannot remember, what is the psychoanalyst or literary theorist doing when he learns a method of analysis that itself involves a repetition of certain skills? A method is only a method because it bears repeating; and yet from a psychoanalytic point of view it is repetition itself that is the problem, that signifies trauma. This is one of the paradoxes that Christopher Bollas and Malcom Bowie examine in their differently eloquent and intriguing books. Embarrassed alike by the subtlety and complexity of the work of art and of the patient, can the theorist and the analyst do more than repeat what they already know? Is theory always more of the same, just Where The Tame Things Are? If theory is, by definition, what we already know, what are its prospects? The future, after all, is the place where our prejudices might not work.

Psychoanalysis may begin with Freud but what it is about does not. Malcom Bowie and Christopher Bollas have been writing some of the most innovatory psychoanalytic theory of the last few years but out of significantly different traditions. There is an unusual stylishness in their writing and an exhilarating ambition. Bollas’s prose, immersed in the poetry of Romanticism and the 19th-century American novel, allows him to be grandiloquent on occasion while being at the same time quite at ease with the tentativeness of his project. His prose often has the evocative resonance that his theory attempts to account for. And as his theory describes psychic life as a kind of haunting, we have to be alert to the echoes in his writing (and sometimes in his overwriting). When, for example, he says about the process of observing the self as an object, ‘emerging from self-experience proper, the subject considers where he has been’, it is integral to the process being described that we can hear the cadence of Coleridge’s glosses on ‘The Ancient Mariner’. And echoes work both ways. Bowie, too, has the virtue of his quite different intellectual affinities, something that is particularly rare in mainstream psychoanalysis, as anyone who has read the specialist journals will know. Though his writing is far too idiosyncratic for pastiche, it is Proust and Mallarmé that we can hear most often in his work. ‘The language of psychoanalysis,’ Bowie writes, ‘offers clues not solutions, calls to action for the interpreter but not interpretations.’ Yet prudence is the unlikely virtue that he keeps promoting in his increasingly subtle readings of Freud and Lacan.

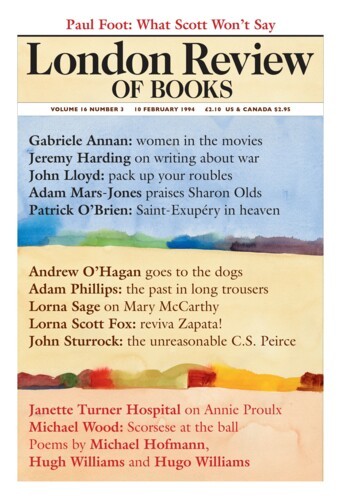

For both Bowie and Bollas it is one of the difficult ironies of psychoanalysis that as a theory it seems to pre-empt the future it is attempting to elicit. Freud’s ‘account of human temporality’, Bowie writes, ‘serves ... to place the future under suspicion, and to keep it there throughout a long theoretical career’. Like Bollas’s definition of a trauma – ‘the effect of trauma is to sponsor symbolic repetition, not symbolic elaboration’ – it is as though, from a psychoanalytic point of view, the future can only be described as, at best, a sophisticated replication of the past, the past in long trousers. Theory itself becomes the symptom it is trying to explain. If in psychoanalytic theory the past, the undigested past, so to speak, is that which always returns – as both symptom and interpretation – how can we return to the future, or get beyond the interminable shock of the old that theory and therapy too easily promote?

In Being a Character Bollas suggests that the future – future selves and states of mind – arises through a process of evocation. Starting with the mother we unwittingly use the world and its objects to bring parts of ourselves to life. A combination of chance and unconscious intention, even our most concerted projects are forms of sleep-walking. ‘Without giving it much thought at all.’ Bollas writes, ‘we consecrate the world with our own subjectivity, investing people places, things and events with a kind of idiomatic significance ... the objects of our world are potential forms of transformation.’ Our chosen objects of interest – anything from the books we read to the way we furnish our rooms or organise our days – are like a personal vocabulary (or even alphabet); we are continually, at our best, ‘meeting idiom needs by securing evocatively nourishing objects’. It is as though we are always trying to live our own language, hoping to find ‘keys to the releasing of our idiom’, what Bollas calls, in one of many felicitous phrases, ‘potential dream furniture’, as we go about setting the scene for the future. Objects – like different artistic media – have very different ‘processional potential’: the object’s ‘integrity’ – whatever it happens to be, what it invites and what it makes impossible – sets limits to its use. The world in Bollas’s view is a kind of aesthetic tool-kit; and unlike most psychoanalytic theorists he doesn’t use a hammer to crack a nut.

It should be clear by now that Bollas has to draw on a repertoire of vocabularies to describe his new psychoanalytic landscape. Orthodox psychoanalysts are not in a hurry to use words like ‘consecrate’ or phrases like ‘idiom needs’; or, indeed, to take the outside world on its own terms. In Bollas’s work the language of Winnicott and of American Pragmatism – of ‘use-value’ – meets up with Wordsworthian Romanticism: the world is sown with, and so made up by, bits of self, and yet retains its separateness, its sacrality, its resistance to absolute invention. In Bollas the self is at once disseminated – all over the place – and intent, in relentless pursuit of ‘props for the dreaming of lived experience’, as he calls them. The articulation of the self, as psychoanalysis has always insisted, is the transformation of the self: to speak is to become different. For Bollas the self is like a rather meditative picaresque hero, the unwitting artist of his own life. Bollas is extraordinarily adept at describing the moment when a person confers significance on an object and is transformed by doing so: and it is whatever baffles this moment that is pathology. The enigma of these meetings, these reciprocal appraisals – their sheer unconsciousness – is Bollas’s overriding preoccupation in this book. And his paradigm for these processes is dreaming. Since ‘a day is a space for the potential articulation of my idiom,’ then, he suggests, living a day may be more like dreaming a dream than waking up from one.

In any one day, Freud showed, quite unbeknown to our conscious selves, we are picking things out to use as dream material in the night ahead. So in what Freud calls the ‘dream-day’ we are living out a kind of unconscious aesthetic; something or someone inside us is selecting what it needs for the night’s work. Things in the day have a significance for us, are meaningful, in ways we know nothing about until we work them back up in the quite different context of the dream. A perceptions, a thought, something overheard is noticed and then transformed by an exceptionally furtive artist. ‘In a very particular sense,’ Bollas writes, ‘we live our life in our own private dreaming.’ Bollas is able without fabricating mysteries to convey an ordinary day as a dream landscape full of unexpectedly intense significance. In its account of living a day as a form of dreaming Being a Character becomes a truly startling book. Without being spooky or vague, Bollas gets us close to the ordinary but absolutely elusive experience of making a dream; showing us how, quite unwittingly, it the most ordinary way, we are choosing objects to speak our secretive languages of self.

Psychoanalytic theory has always had problem keeping the unconscious unconscious: it usually becomes a nastier, or more ingenious consciousness, a wished-for or a dreaded one. What is distinctive about Bollas’s work is his commitment to the unconscious – the unconsciousness of everyday life – without becoming speechless or too mystical in the process (the best and the worst of psychoanalytic theory always verges on the mystical). But how much real unconsciousness can one allow into the picture and still go on practising and believing in psychoanalysis? If psychoanalysis is really a sleep-walking à deux, what is the analyst and, for that matter, the patient supposed to be doing? Taking Freud seriously (which doesn’t mean taking him all or taking him earnestly) involves acknowledging, as Bollas writes, that ‘most of what transpires in psychoanalysis – as in life itself – is unconscious.’ Since for Bollas dreaming is the model, patient and analyst use each other as part, though an intense part, of each other’s dream day. The official emphasis is on the patient using the analyst as a transformational object, but in Bollas’s model the reciprocity of the analytic process cannot be concealed. And the aim is not so much understanding – finding out which character you are – but a freeing of the potentially endless process of mutual invention and reinvention. For Bollas, pathology is whatever it is in the environment and/or the self that sabotages or stifles both a person’s inventiveness, and their belief in this inventiveness as an open-ended process. It is a psychoanalysis committed to the pleasures and the freedoms of misunderstandings, and which Freud called dream-work; distortion in the service of desire: not truth, except in its most provisional sense, but possibility. The core catastrophe in many of Bollas’s powerful clinical vignettes is of being trapped in someone else’s (usually the parents’) dream or view of the world: psychically paralysed for self-protection in a place without the freedom of perspectives. Here what Bollas calls ‘that instinct to elaborate oneself’ is thwarted: one is fixed in someone else’s preconception. Bollas’s use of the word ‘instinct’ is another instance where he joins the language of psychoanalysis with the languages of Romanticism.

In four remarkable, linked essays in the book – ‘Cruising in the Homosexual Arena’, ‘Violent Innocence’, ‘The Fascist State of Mind’ and ‘Why Oedipus?’ – Bollas explores the causes and consequences of stifling a person’s internal repertoire of states of mind. For Bollas, so-called mental health (or rather, his version of a good life) entails the tolerance and enjoyment of inner complexity: the ability to use and believe in a kind of internal ‘parliament’, full of conflicting, dissenting and coercive views. There is no final resolution here but rather a genuinely political and psychic vigilance in the face of the insidious violence of over-simplification. ‘Whatever the anxiety or need that sponsors the drive to certainty, which becomes the dynamic in the fascist construction, the outcome is to empty the mind of all opposition (on the actual stage of world politics, to kill the opposition).’ This essay makes one wonder which parts of the self need to be expelled to sustain any kind of political allegiance; what happens to greed in left-wing sympathies or empathy in certain versions of Toryism? Unusually activist for a psychoanalyst, Bollas offers us both ways of recognising the seductions of apparent political and psychic innocence – being on the side of Goodness, Truth and Logic – and actual strategies for managing them. One of the bemusing things about this remarkable book is that it is at once genuinely radical and curiously comforting.

Bollas’s lucid commitment to complexity – which never degenerates into a stultifying relativism – has, as it were, its own complication built into it. For Bollas, the ‘achievement’ of the Oedipus complex is that the ‘child comes to understand something about the oddity of possessing one’s own mind’; and this means being a mind among others. The child inherits, or wakes up to, the notion of point of view: I’m not only my mother’s son and possible lover, but also my father’s, and my mother looks different from my father’s point of view, and my desire for my father looks different from my mother’s point of view, and so on. The superego – the internalised paternal prohibition – ‘announces’, Bollas writes, ‘the presence of perspective ... the child discovers the multiplicity of points of view.’ And this ever proliferating multiplicity, informed by desire, will become the ‘it’ he will call his mind. It is easy to see, as Bollas intimates, how it can begin to feel overwhelming and persecutory: too much music on at the same time. In one of the best speculative moments in the book, Bollas suggests the possibility that many people cannot bear the complexity of their own minds and so take flight into the collusive solace of coupledom, or family life, or group allegiance. The ‘madness’ of being insistently with others is preferable to the ‘madness’ of one’s mind. ‘Given the ordinary unbearableness of this complexity,’ Bollas writes, ‘I think that the human individual partly regresses in order to survive, but this retreat has been so essential to human life that it has become an unanalysed convention, part of the religion of everyday life. We call this regression “marriage” or “partnership”, in which the person becomes part of a mutually interdependent couple that evokes and sustains the bodies of the mother and the father, the warmth of the pre-Oedipal vision of life, before the solitary recognition of subjectivity grips the child.’ In Bollas’s terms this proposal itself might function as an ‘object with evocative integrity’. What would it be like to live in a word in which people welcomed their own, and therefore other people’s, complication: in which people did not allow their children to be simplified by conventional education, or coercive belief systems? Traditionally, the numinous thing has been to simplify the moral life.

For Bollas, trauma is that which oversimplifies the self; that which, because of the suffering entailed, leaves people with an aversion to their own complexity. Some people, Bollas writes, for good reasons of their own, ‘insist that the invitational feature of the object be declined ... they may narrow the choice of objects, eliminating those with high evocative potential.’ Curiosity is a threat to the self as idol; each new person we meet may call up in us something unfamiliar. So from Bollas’s point of view psychoanalysis, as a form of therapy, has two implicit aims: to release – to analyse the obstacles to – the internal radar a person needs in order to locate the objects he requires for self-transformation. And to elicit, and enable a person to use, their essential complexity. It is part of the subtlety of this book to make these projects seem compatible.

Like Being a Character, Psychoanalysis and the Future of Theory is about metamorphosis, the pull of the future against the drag of the past. For Bowie works of art are ‘transformational devices’ (for Bollas anything might be, though art is always a promising candidate); and the Freudian unconscious ‘prevents meaning from reaching fullness, completion, closure, consummation’. This does, indeed, exempt meaning from a lot of different things, and leaves it with an unenviable fate. It is, of course, very difficult now to write interestingly about an aversion to closure, a world in which because nothing stops nothing starts either. All modern theory is written in the shade of Heraclitus. But however inclined we are to the idea of process, our language seems to need punctuation. A provisional stop makes a difference. Bowie manages to find, in his shrewd prose, interesting ways to describe this relationship between the fluent and the fixed that theory cannot avoid confronting. It was Bowie’s regard for this tension in Lacan between, as it were, the will to mathematical formulation and the compulsion to pun that made his book on Lacan so exhilarating and intelligible. By not taking sides he avoided being evasive. In Psychoanalysis and the Future of Theory, elaborating these same dilemmas, Bowie concentrates on what he calls the ‘world of unstoppable transformational process’ which ‘Freud’s new psychology brought into view’. Unstoppablity, of course, is only visible if we know what a stop looks like. For Bowie, the future of theory, not unlike the future of the psychoanalytic patient, depends on this, on the ‘irreducibility, the uncontainability, the unstoppability of the signifying process’. Words do stop somewhere, but psychoanalysis, like literary theory, should not be the art of having the last word. Last words are a different thing entirely.

But having said that about ‘the signifying process’ what is there left to say? In the essay that gives the book its title, Bowie shows how Freud, by prioritising the past, made the future a virtually redundant category in psychoanalytic theory. It is one of the important paradoxes of psychoanalysis that for Freud wishes lead one into the past and not the future. ‘Human beings,’ Bowie writes, ‘are devoted to the optative mood. This is the time dimension that all desiring creatures inhabit, and “if only such and such were the case” is its characteristic syntactic structure.’ But as ‘such and such’ is in the past the future comes out as more of the same (though this more is always becoming less). In Bowie’s view it took Lacan’s brilliant enquiries into human temporality (inspired by Heidegger) to reveal how ‘past, present and future will always stand outside each other, unsettle each other, and refuse to cohere.’ Bowie’s unusual image of those quasi-allegorical figures Past, Present and Future ‘standing outside each other’, squabbling like an unhappy family, is easy to miss in a writer who, unlike Lacan, keeps his artfulness under wraps.

Though Lacan, as Bowie says, was committed to the ‘rediscovery of a futurity intrinsic to the structure of the human passions’, and, therefore, to the unknowable in human experience, he also had the fatal weakness of all those who are fanatically against all forms of totalisation (the complete picture) in the so-called human sciences: a love of system. On the one hand, Bowie writes, Lacan is ‘fascinated by the sciences of exact measurement’ and, in his theory, by ‘dreams of a perfectly calculable human subject’, while on the other, he is committed, as a form of virtual revelation, to ‘astonishing time-teasing syntactic and semantic display’. When Blake proposed that he should build his own system or else be enslaved by another man’s, he was, of course, acknowledging the powerful fascination of systems, not paying tribute to the individual’s freedom. So what can the system-building theorist do with this dilemma, and with Lacan himself? Either stick to the scheme and make it more rigorous, copy the exhilarating rhetoric; or, as Bowie rightly prefers, ‘learn to unlearn the Lacanian idiom in the way Lacan unlearnt the Freudian idiom’. This is a salutary suggestion in so far as it might help some people avoid the humiliation – the awful prose style – of the disciple. To be a follower in psychoanalysis is to miss the point. Disciples are the people who haven’t got the joke. And historically, in psychoanalysis, disciples enact the catastrophe their leaders were trying to avert; Freudians become ascetic prigs, Winnicottians become rigorously spontaneous, Kleinians become enviously narrow-minded, Lacanians mirror the master, and so on.

Bowie proposes that the future of psychoanalytic theory depends on an interanimating relationship with other disciplines and a new fashion of old-fashioned values; ‘perhaps the best hope for the psychoanalyst,’ he writes, ‘lies not in theory at all, but in the old-fashioned arts of speaking opportunely and knowing when to stop.’ And a tactful psychoanalysis sufficiently alert to futures could teach literary theorists to perform, ‘flexed, tensed, desirous and prospective critical performances’. The critical question might be: what do I and this text/patient want to be next? What are we going to use each other to become? Most literary and psychoanalytic theory spends its time establishing its ground and finding positions. Bowie proposes that they find what they did not know they were looking for. As a critic he is interested in the moment – in a sense, the psychoanalytic moment – when a person seems ‘suddenly to be speaking or behaving from an alien region’.

Bowie wants the complexity of art to replace, or become the paradigm for, what have become the stultifications of theory. No theory, not even the addictive theory of psychoanalysis, can ‘still the rage of a literary text’. Sounding for once more like Carlyle – or perhaps Arnold – he prophesies that ‘by the year 2000 “theory” will have rediscovered art and the threatened but glorious futures that art contains.’ For some people, of course, this begs all the questions – whose art and whose futures? – but it also confronts the absurd omniscience and righteous indignation that goes on passing for much critical theory. There is no reason that a plea for the value of complexity should in itself be reactionary or complacently knowing.

Bowie’s second essay in the book, ‘Freud and Art, or What Will Michelangelo’s Moses Do Next?’ is likely to modify the suspicions aroused by his prediction about the forthcoming death of the theorist. This brilliant chapter functions as the critical consciousness of the book as it teases out Freud’s perplexed and contradictory relationship to art and artists. In Bowie’s view, Freud idealised the past; Bowie himself seems to idealise art: in this chapter these acts of psychic denial are themselves analysed. For Freud, Bowie writes, art works represented ‘the psychical life lived in a triumphant mode’: ‘by way of art the human being could remove himself for a time from his wretchedness.’ It is Freud’s ‘strangeness’ about art, his ‘impatient’ and ‘appropriative’, and particularly competitive dealings with the art of the past, that exercise Bowie. Once again it is the war between excess and conclusiveness that he is quick to notice. Freud’s relationship to literature in The Interpretation of Dreams – a ‘thinning out’ Bowie calls it – is mirrored in his relationship to his dreams. The dreams, Bowie observes, have this ‘constant air of semantic overflow and dispersal’, while Freud himself insisted ‘upon parsimony in his interpretative procedures’. Theory or interpretation are all we are left with after the artwork or the dream have been made habitable. Literature is what gets lost in interpretation. ‘From an extremely parsimonious set of causes,’ Bowie writes, ‘springs a glittering array of effects.’

Bowie is on the side of the effects. To satisfy Freud’s scientific superego, ‘the grammar of interpretation had to be purged of merely wish-bearing constructions.’ For Bowie, a good interpretation is one that re-enacts or discerns the temporal complexity of the object, its mobility of wish and retrospection. It is the bizarre meshing of the future with the past that Bowie wants to recuperate for the act of interpretation. If it fails to do this, ‘analysis explains the work of art, and immobilises it in the process.’ Art becomes merely an integral part of the larger self-fulfilling prophecy called psychoanalysis, which by explaining everything finds nothing new under the sun. Art is then ‘granted no higher privilege ... than that of accrediting psychoanalysis all over again by adding an aura of cultural value and prophetic grandeur to its scientific claims’. It is the Freud of interminable, digressive meanings, not the Freud in search of causes, that both Bollas and Bowie in their separate ways promote.

The ‘new’ Freud Bowie recommends here is ‘a dramatist, a novelist, a fabulist and, above all perhaps, a rhetorician’. Bollas’s Freud is the exemplary and inspiring human subject who ‘becomes the dream work of his own life’; who found a way of describing this banal and enigmatic experience. But both these books, committed as they are to a more ‘literary’ psychoanalysis, make continual reference, by analogy or allusion, to music – the art form Freud is known to have disliked. It may also be useful, Bowie and Bollas intimate, to think of the unconscious as structured like a piece of music. If we were to think like this what would psychoanalytic interpretation have to become? Perhaps the function of psychoanalysis in the future will not be to inform but to evoke.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.