‘My mother is such a bloody rambling fool,’ wrote Philip Larkin in 1965, ‘that half the time I doubt her sanity. Two things she said today, for instance, were that she had “thought of getting a job in Woolworth’s” and that she wanted to win the football pools so that she could “give cocktail parties”.’ Eva Larkin was 79 at the time so that to see herself presiding over the Pick’n’ Mix counter was a little unrealistic and her chances of winning the football pools were remote as she didn’t go in for them. Still, mothers do get ideas about cocktail parties, or mine did anyway, who’d never had a cocktail in her life and couldn’t even pronounce the word, always laying the emphasis (maybe out of prudery) on the tail rather than the cock. I always assumed she got these longings from women’s magazines or off the television and maybe Mrs Larkin did too, though ‘she never got used to the television’ – which in view of her son’s distrust of it is hardly surprising.

Mrs Larkin went into a home in 1971, a few months after her son had finished his most notorious poem, ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad’. She never read it (Larkin didn’t want to ‘confuse her with information about books’) but bloody rambling fool or not she shared more of her son’s life and thoughts than do most mothers, or at any rate the version he gave her of them in his regular letters, still writing to her daily when she was in her eighties. By turns guilty and grumbling (‘a perpetual burning bush of fury in my chest’), Larkin’s attitude towards her doesn’t seem particularly unusual, though his dutifulness does. Even so, Woolworth’s would hardly have been her cup of tea. The other long-standing lady in Larkin’s life (and who stood for a good deal), Monica Jones, remarks that to the Larkins the least expenditure of effort was ‘something heroic’: ‘Mrs Larkin’s home was one in which if you’d cooked lunch you had to lie down afterwards to recover.’ Monica, one feels, was more of a Woolworth’s supervisor than a counter assistant. ‘I suppose,’ wrote Larkin, ‘I shall become free [of mother] at 60, three years before the cancer starts. What a bloody, sodding awful life.’ His, of course, not hers. Eva died in 1977 aged 91, after which the poems more or less stopped coming. Andrew Motion thinks this is no coincidence.

Larkin pinpointed 63 as his probable departure date because that was when his father went, turned by his mother into ‘the sort of closed, reserved man who would die of some thing internal’. Sydney Larkin was the City Treasurer of Coventry. He was also a veteran of several Nuremberg rallies, a pen-pal of Schacht’s, and had a statue of Hitler on the mantelpiece that gave the Nazi salute. Sydney made no secret of his sympathies down at the office: ‘I see that Mr Larkin’s got one of them swastika things up on his wall now. Whatever next?’ Next was a snip in the shape of some cardboard coffins that Sydney had cannily invested in and which came in handy when Coventry got blitzed, the Nazi insignia down from the wall by this time (a quiet word from the Town Clerk). But he didn’t change his tune, still less swap the swastika for a snap of Churchill, who had, he thought, ‘the face of a criminal in the dock’.

To describe a childhood with this grotesque figure at the centre of it as ‘a forgotten boredom’ seems ungrateful of Larkin, if not untypical, even though the phrase comes from a poem not an interview, so Larkin is telling the truth rather than the facts. Besides, it would have been difficult to accommodate Sydney in a standard Larkin poem, giving an account of his peculiar personality before rolling it up into a general statement in the way Larkin liked to do. Sylvia Plath had a stab at that kind of thing with her ‘Daddy’, though she had to pretend he was a Nazi, while Larkin’s dad was the real thing. Still, to anyone (I mean me) whose childhood was more sparsely accoutred with characters, Larkin’s insistence on its dullness is galling, if only on the ‘I should be so lucky’ principle.

As a script, the City Treasurer and his family feels already half-written by J.B. Priestley; were it a film Sydney (played by Raymond Huntley) would be a domestic tyrant, making the life of his liberal and sensitive son a misery, thereby driving him to Art. Not a bit of it. For a start the son was never liberal (‘true blue’ all his life, Monica says) and with a soft spot for Hitler himself. Nor was the father a tyrant; he introduced his son to the works of Hardy and, more surprisingly, Joyce, did not regard jazz as the work of the devil, bought him a subscription to the magazine Downbeat (a signpost here) and also helped him invest in a drum-kit. What if anything he bought his daughter Kitty and what Mrs Larkin thought of it all is not recorded. Perhaps she was lying down. The women in the Larkin household always took second place, which, in Motion’s view, is half the trouble. Kitty, Larkin’s older sister (‘the one person in the world I am confident I am superior to’), scarcely figures at all. Hers would, I imagine, be a dissenting voice, more brunt-bearing than her brother where Mrs Larkin was concerned and as undeceived about the poet as were most of the women in his life.

Whatever reservations Larkin had about his parents (‘days spent in black, twitching, boiling HATE!!!’), by Oxford and adulthood they had modulated, says Motion, into ‘controlled but bitter resentment’. This doesn’t stop Larkin sending poems to his father (‘I crave / The gift of your courage and indifference’) and sharing his thoughts with his mother (‘that obsessive snivelling pest’) on all manner of things; in a word treating them as people rather than parents. Its nothing if not ‘civilised’ but still slightly creepy and it might have come as a surprise to Kingsley Amis, in view of their intimate oath-larded letters to one another, that Larkin, disappointed of a visit, should promptly have complained about him (‘He is a wretched type’) to his mother.

‘Fearsome and hard-driving’, Larkin senior is said never to have missed the chance of slipping an arm round a secretary and though Larkin junior took a little longer about it (twenty-odd years in one case), it is just one of the ways he comes to resemble his father as he grows older, in the process getting to look less like Raymond Huntley and more like Francis L. Sullivan and ‘the sort of person that democracy doesn’t suit’.

Larkin’s choice of profession is unsurprising because from an early age libraries had been irresistible. ‘I was an especially irritating kind of borrower, who brought back in the evening the books he had borrowed in the morning and read in the afternoon. This was the old Coventry Central Library, nestling at the foot of the unbombed cathedral, filled with tall antiquated bookcases (blindstamped Coventry Central Libraries after the fashion of the time) with my ex-schoolfellow Ginger Thompson ... This was my first experience of the addictive excitement a large open-access public library generates.’ When he jumped over the counter, as it were, things were rather different though father’s footsteps come into this too: it you can’t be a gauleiter being a librarian’s the next best thing. When called upon to explain his success as a librarian, Larkin said: ‘A librarian can be one of a number of things ... a pure scholar, a technician ... an administrator or he ... can be just a nice chap to have around, which is the role I vaguely thought I filled.’ Motion calls this a ‘typically self-effacing judgment’ but it’s also a bit of a self-deluding one. It’s a short step from the jackboot to the book-jacket and by all accounts Larkin the librarian could be a pretty daunting figure. Neville Smith remembers him at Hull stood at the entrance to the Brynmor Jones, scanning the faces of the incoming hordes, the face heavy and expressionless, the glasses gleaming and the hands, after the manner of a soccer player awaiting a free-kick on the edge of the penalty area, clasped over what is rumoured to have been a substantial package. ‘FUCK OFF, LARKIN, YOU CUNT’ might have been the cheery signing-off in a letter from Kingsley Amis: it was actually written up on the wall of the library lifts, presumably by one of those ‘devious, lazy and stupid’ students who persisted in infesting the librarian’s proper domain and reading the books.

It hadn’t always been like that, though, and Larkin’s first stint at Wellington in Shropshire, where in 1943 he was put in charge of the municipal library, was a kind of idyll. Bitterly cold, gas-lit and with a boiler Larkin himself had to stoke, the library had an eccentric collection of books and a readership to match. Here he does seem to have been the type of librarian who was ‘a nice chap to have around’, one who quietly got on with improving the stock while beginning to study for his professional qualifications by correspondence course. Expecting ‘not to give a zebra’s turd’ for the job he had hit upon his vocation.

Posts at Leicester and Belfast followed until in 1955 he was appointed Librarian at the University of Hull with the job of reorganising the library and transferring it to new premises. Moan as Larkin inevitably did about his job, it was one he enjoyed and which he did exceptionally well. The students may have been intimidated by him but he was popular with his staff and particularly with the women. Mary Judd, the librarian at the issue desk at Hull, thought that ‘most women liked him more than most men because he could talk to a woman and make her feel unique and valuable.’ In last year’s Selected Letters there is a photo of him with the staff of the Brynmor Jones and, Larkin apart, there is not a man in sight. Surrounded by his beaming middle-aged assistants – with two at least he was having or would have an affair – he looks like a walrus with his herd of contented cows There was contentment here for him, too, and one of his last poems, written when deeply depressed, is about a library.

New eyes each year

Find old books here,

And new books, too,

Old eyes renew;

So youth and age

Like ink and page

In this house join,

Minting new coin.

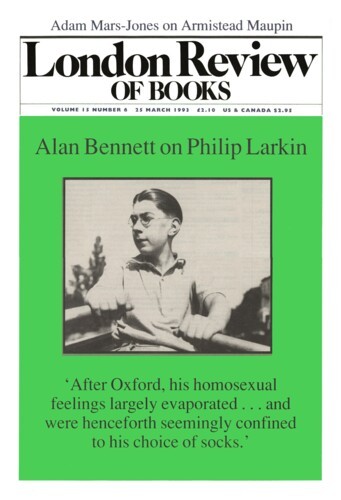

Much of Motion’s story is about sex, not getting it, not getting enough of it or getting it wrong. For a time it seemed Larkin could go either way and there are a few messy homosexual encounters at Oxford, though not Brideshead by a long chalk, lungings more than longings and not the stuff of poetry except as the tail-end of ‘these incidents last night’. After Oxford Larkin’s homosexual feelings ‘evaporated’ (Motion’s word) and were hence-forth seemingly confined to his choice of socks. At Wellington he starts walking out with Ruth Bowman, ‘a 16-year-old schoolgirl and regular borrower from the library’. This period of Larkin’s life is quite touching and reads like a Fifties novel of provincial life, though not one written by him so much as by John Wain or Keith Waterhouse. Indeed Ruth sounds (or Larkin makes her sound) like Billy Liar’s unsatisfactory girlfriend, whose snog-inhibiting Jaffa Billy hurls to the other end of the cemetery. Having laid out a grand total of 15s. 7d. on an evening with Ruth, Larkin writes to Amis:

Don’t you think it’s ABSOLUTELY SHAMEFUL that men have to pay for women without BEING ALLOWED TO SHAG the women afterwards AS A MATTER OF COURSE? I do: simply DISGUSTING. It makes me ANGRY. Everything about the ree-lay-shun-ship between men and women makes me angry. It’s all a fucking balls-up. It might have been planned by the army or the Ministry of Food.

To be fair, Larkin’s foreplay could be on the funereal side. In the middle of one date with Ruth, Larkin (22) lapsed into silence. Was it something she’d said? ‘No, I have just thought what it would be like to be old and have no one to look after you.’ This was what Larkin would later refer to as ‘his startling youth’. ‘He could,’ says Ruth, ‘be a draining companion.’

In the end one’s sympathies, as always in Larkin’s affairs, go to the woman and one is glad when Ruth finally has him sized up and decides that he’s no hubby-to-be. And he’s glad too, of course. Ruth has Amis well sussed besides. ‘He wanted,’ she says, ‘to turn Larkin into a “love ’em and lose ’em type”,’ and for a moment we see these two leading lights of literature as what they once were, the Likely Lads, Larkin as Bob, Amis as Terry and Ruth at this juncture the terrible Thelma.

Looking back on it now Ruth says: ‘I was his first love and there’s something special about a first love, isn’t there?’ Except that love is never quite the right word with Larkin, ‘getting involved’ for once not a euphemism for the tortuous process it always turns out to be. ‘My relations with women,’ he wrote, ‘are governed by a shrinking sensitivity, a morbid sense of sin, a furtive lechery. Women don’t just sit still and back you up. They want children; they like scenes; they want a chance of parading all the empty haberdashery they are stocked with. Above all they like feeling they own you – or that you own them – a thing I hate.’ A.C. Benson, whose medal Larkin was later to receive from the Royal Society of Literature, put it more succinctly, quoting (I think) Aristophanes: ‘Don’t make your house in my mind.’ Though with Larkin it was ‘Don’t make your house in my house either,’ his constant fear being that he will be moved in on, first by his mother and then, when she’s safely in a home, some other scheming woman. When towards the finish Monica Jones does manage to move in it’s because she’s ill and can’t look after herself, and so the cause of a great deal more grumbling. With hindsight (Larkin’s favourite vantage-point) it would have been wiser to have persisted with the messy homosexual fumblings, one of the advantages of boys that they’re more anxious to move on than in. Not, of course, that one has a choice, ‘something hidden from us’ seeing to that.

Larkin’s earliest poems were published by R.A. Caton of the Fortune Press. Caton’s list might have been entitled ‘Poetic Justice’, as besides the poetry it included such titles as Chastisement Across the Ages and an account of corporal punishment as meted out to women in South German prisons; since Larkin’s tastes ran to both poetry and porn there is poetic justice in that too. He found that he shared his interest in dirty books with ‘the sensitive and worldly-wise’ Robert Conquest and together they went on expeditions, trawling the specialist shops for their respective bag in a partnership that seems both carefree and innocent. Unusual, too, as I had always thought that porn, looking for it and looking at it, was something solo. Conquest would also send him juicy material through the post and on one occasion conned the fearful Larkin into thinking the law was on his tracks and ruin imminent; he made him sweat for two or three days before letting him off the hook. That Larkin forgave him and bore no ill-will seems to me one of the few occasions outside his poetry when he comes close to real generosity of spirit.

Timorous though Larkin was he was not shamefaced and made no secret of his predilections. Just as Elsie, secretary to his father, took her bottom-pinching Führer-friendly boss in her stride, so Betty, the secretary to the son, never turned a hair when she came across his lunchtime reading in the shape of the splayed buttocks of some gym-slipped tot, just covering it briskly with a copy of the Library Association Record and carrying on cataloguing. One of the many virtues of Motion’s book is that it celebrates the understanding and tolerance of the average British secretary and the forbearance of women generally. As, for instance, the friend to whom Larkin showed a large cupboard in his office, full of both literary and photographic porn ‘What is it for?’ she asked. ‘To wank to, or with, or at’ was Larkin’s reply, which Motion calls embarrassed, though it doesn’t sound so, the question, or at any rate the answer, presumably giving him a bit of a thrill. Like the other documents of his life and his half-life, the magazines were carefully kept, if not catalogued, in his desolate attic, though after twenty-odd years’ perusal they must have been about as stimulating as Beowulf.

One unremarked oddity in the Selected Letters is a note from Larkin to Conquest in 1976 mentioning a visit to Cardiff where he had ‘found a newsagent with a good line in Yank homo porn, in quite a classy district too. Didn’t dare touch it.’ I had assumed that in the matter of dirty magazines, be it nurses, nuns or louts in leather, you found whatever knocked on your particular box and stuck to it. So what did Larkin want with ‘this nice line in homo porn’? Swaps? Or hadn’t all that messy homosexuality really evaporated? Certainly pictured holidaying on Sark in 1955 he looks anything but butch. One here for Jake Balokowsky.

I am writing this before the book is published, but Larkin’s taste for pornography is already being touted by the newspapers as something shocking. It isn’t but, deluded liberal that I am, I persist in thinking that those with a streak of sexual unorthodoxy ought to be more tolerant of their fellows than those who lead an entirely godly, righteous and sober life. Illogically I tend to assume that if you dream of caning schoolgirls’ bottoms it disqualifies you from dismissing half the nation as work-shy. It doesn’t, of course; more often it’s the other way round but when Larkin and Conquest rant about the country going to the dogs there’s a touch of hypocrisy about it. As an undergraduate Larkin had written two facetious novels set in a girls’ school under the pseudonym of Brunette Coleman. It’s tempting to think that his much advertised adoration of Mrs Thatcher (‘What a superb creature she is, right and beautiful!’) owes something to the sadistic headmistress of St Bride’s, Miss Holden. ‘As Pam finally pulled Marie’s tunic down over her black-stockinged legs Miss Holden, pausing only to snatch a cane from the cupboard in the wall, gripped Marie by her hair and, with strength lent by anger, forced down her head till she was bent nearly double. Then she began thrashing her unmercifully, her face a mask of ferocity, caring little where the blows fell, as long as they found a mark somewhere on Marie’s squirming body. At last a cry was wrung from her bloodless lips and Marie collapsed on the floor, twisting in agony, her face hidden by a flood of amber hair.’ Whether Mr Heseltine is ever known as Marie is a detail; that apart it could be a verbatim extract from A History of Cabinet Government 1979-90.

Meeting Larkin at Downing Street in 1980 Mrs Thatcher gushed that she liked his wonderful poem about a girl. ‘You know,’ she said, ‘“Her mind was full of knives.”’ The line is actually ‘All the unhurried day / Your mind lay open like a drawer of knives,’ but Larkin liked to think that Madam knew the poem or she would not have been able to misquote it. Inadequate briefing seems a likelier explanation and anyway, since the line is about an open mind it’s not surprising the superb creature got it wrong.

Mrs Thatcher’s great virtue, Larkin told a journalist, ‘is saying that two and two makes four, which is as unpopular nowadays as it always has been’. What Larkin did not see was that it was only by banking on two and two making five that institutions like the Brynmor Jones Library could survive. He lived long enough to see much of his work at the library dismantled; one of the meetings he was putting off before his death was with the Vice-Chancellor designate, who was seeking ways of saving a quarter of a million pounds and wanted to shrink the library by hiving off some of its rooms. That was two and two making four.

Andrew Motion makes most of these points himself but without rancour or the impatience this reader certainly felt. Honest but not prurient, critical but also compassionate, Motion’s book could not be bettered. It is above all patient and with no trace of the condescension or irritation that are the hazards of biography. He is a sure guide when he relates the poetry to the life, even though the mystery of where the poetry came from, and why, and when, sometimes defeats him. But then it defeated Larkin or his writing would not have petered out when it did. For all that, it’s a sad read and Motion’s patience with his subject is often hard to match. Larkin being Larkin, though, there are lots of laughs and jokes never far away. Before he became a celebrity (and wriggle though he did that was what he became) and one heard gossip about Larkin it was generally his jokes and his crabbiness that were quoted. ‘More creakings from an old gate’, was his dedication in Patrick Garland’s volume of High Windows and there were the PCs (which were not PC at all) he used to send to Charles Monteith, including one not quoted here or in the Selected Letters. Along with other Faber authors Larkin had been circularised asking what events, if any, he was prepared to take part in to mark National Libraries Week. Larkin wrote back saying that the letter reminded him of the story of Sir George Sitwell being stopped by someone selling flags in aid of National Self-Denial Week: ‘For some of us,’ said Sir George, ‘every week is self-denial week.’ ‘I feel,’ wrote Larkin, ‘exactly the same about National Libraries Week.’ The letters are full of jokes. ‘I fully expect’, he says of ‘They fuck you up, your mum and dad’, ‘to hear it recited by 1000 Girl Guides before I die’; he gets ‘a letter from a whole form of Welsh schoolgirls, seemingly inviting mass coition. Where were they when I wanted them?’ And in the cause of jokes he was prepared to dramatise himself, heighten his circumstances, darken his despair, claim to have been a bastard in situations where he had actually been all charm. What one wants to go on feeling was that, the poems apart, the jokes were the man and the saddest thing about this book and the Selected Letters is to find that they weren’t, that beyond the jokes was a sphere of gloom, fear and self-pity that nothing and no one touched. And so far from feeling compassion for him on this score, as Motion always manages to do, I just felt impatient and somehow conned.

Trying to locate why takes one back to Auden:

A writer, or at least a poet, is always being asked by people who should know better: ‘Whom do you write for?’ The question is, of course, a silly one, but I can give it a silly answer. Occasionally I come across a book which I feel has been written especially for me and for me only. Like a jealous lover I don’t want anybody else to hear of it. To have a million such readers, unaware of each other’s existence, to be read with passion and never talked about, is the daydream, surely, of every author.

Larkin was like that, certainly after the publication of The Less Deceived and even for a few years after The Whitsun Weddings came out. Because his poems spoke in an ordinary voice and boasted his quiescence and self-deprecation one felt that here was someone to like, to take to and whose voice echoed one’s inner thoughts and that he was, as he is here engagingly indexed (under his initials), a PAL. So that in those days, certainly until the mid-Seventies, Larkin seemed always a shared secret. The great and unexpected outpouring of regret when he died showed this sentiment to have been widespread and that through the public intimacy of his poetry he had acquired a constituency as Betjeman, partly through being less introspective and more available, never entirely did. And while we did not quite learn his language or make him a pattern to live and to die, what one is left with now is a sense of betrayal which is quite difficult to locate and no less palpable for the fact that he never sought to mislead the public about his character, particularly as he got older.

They were deceived, though. When Anthony Thwaite published the Selected Letters last year the balance of critical opinion was disposed to overlook – or at any rate excuse – his racist and reactionary sentiments as partly a joke, racism more pardonable these days in the backlash against political correctness. Besides it was plain that in his letters Larkin exaggerated; he wasn’t really like that. Motion’s book closes down this escape route. ‘You’ll be pleased to see the black folk go from the house over the way,’ he says in a 1970 letter, and were it written to Amis or Conquest it might get by as irony, wit even, a voice put on. But he is writing to his mother for whom he did not put on a voice, or not that voice anyway. Did it come with the flimsiest of apologies it would help (‘I’m sorry,’ as I once heard someone say, ‘but I have a blind spot with black people’). How were the blacks across the way different from ‘Those antique negroes’ who blew their ‘flock of notes’ out of ‘Chicago air into/A huge remembering pre-electric horn/The year after I was born’? Well, they were in Chicago for a start, not Loughborough. Wanting so much for him to be other, one is forced against every inclination to conclude that, in trading bigotries with an eighty-year-old, Larkin was sincere; he was being really himself:

I want to see them starving

The so-called working class

Their weekly wages halving

Their women stewing grass.

The man who penned that might have been pleased to come up with the slogan of the 1968 Smethwick by-election, ‘If you want a nigger neighbour, Vote Labour.’ Larkin refused the Laureateship because he couldn’t turn out poetry to order. But if he could churn out this stuff for his letters and postcards he could have turned an honest penny on the Sun any day of the week.

Then there is Larkin, the Hermit of Hull. Schweitzer in the Congo did not derive more moral credit than Larkin did for living in Hull. No matter that of the four places he spent most of his life, Hull, Coventry, Leicester and Belfast, Hull is probably the most pleasant; or that poets are not and never have been creatures of capital: to the newspapers, as Motion says, remoteness is synonymous with integrity. But Hull isn’t even particularly remote. Ted Hughes, living in Devon, is further from London (as the crow flies, of course) than Larkin ever was but that he gets no credit for it is partly the place’s fault, Devon to the metropolitan crowd having nothing on the horrors of Hull. Hughes, incidentally, gets much the same treatment here as he did in the Selected Letters, more pissed on than the back wall of the Batley Working Men’s club before a Dusty Springfield concert.

Peter Cook once did a sketch when, dressed as Garbo, he was filmed touring the streets in an open-topped limousine shouting through a megaphone ‘I want to be alone’. Larkin wasn’t quite as obvious as that but poetry is a public address system too and that his remoteness was so well publicised came about less from his interviews or personal pronouncements than from the popularity of poems like ‘Here’ and ‘The Whitsun Weddings’ which located Larkin, put him on (and off) the map and advertised his distance from the centre of things.

That Hull was the back of beyond in the Fifties wasn’t simply a London opinion; it prevailed in Hull itself. In 1959 I tentatively applied there for a lectureship in medieval history and the professor kicked off the interview by emphasising that train services were now so good that Hull was scarcely four hours from King’s Cross. It wasn’t that he’d sensed in me someone who’d feel cut off from the vivifying currents of capital chic, rather that my field of study was the medieval exchequer, the records of which were then at Chancery Lane. Still, there was a definite sense that a slow and stopping train southwards was some kind of lifeline and that, come a free moment, there one was going to be aimed. Even Larkin himself was aimed there from time to time, and though his social life was hardly a hectic round, he put himself about more than he liked to think.

Until I read Motion’s book I had imagined that Larkin was someone who had largely opted out of the rituals of literary and academic life, that he didn’t subscribe to them and wasn’t taken in by them. Not a bit of it. There are umpteen formal functions, the poet dutifully getting on the train to London for the annual dinner of the Royal Academy, which involves a visit to Moss Bros (‘and untold expense’); there’s at least one party at Buckingham Palace, a Foyle’s Literary Luncheon at which he has to give a speech, there are dinners at his old college and at All Souls and while he does not quite go to a dinner up a yak’s arse he does trundle along to the annual festivities of the Hull Magic Circle. Well, the chairman of the library committee was an enthusiastic conjuror, Larkin lamely explains. When Motion says that Larkin had reluctantly to accept that his emergence as a public man would involve more public duties it’s the ‘reluctantly’ one quibbles with. Of course there’s no harm in any of these occasions if you’re going to enjoy yourself. But Larkin seemingly never does, or never admits that he does. But if he didn’t, why did he go? Because they are not difficult to duck. Amis has recorded how much pleasanter life became when he realised he could refuse invitations simply by saying ‘don’t do dinners’ – a revelation comparable to Larkin’s at Oxford when it dawned on him he could walk out of a play at the interval and not come back. But Larkin did do dinners and not just dinners. He did the Booker Prize, he did the Royal Society of Literature, he did the Shakespeare Prize; he even did a dinner for the Coventry Award of Merit. Hermit of Hull or not, he dutifully turns up to collect whatever is offered to him, including a sackful of honours and seven honorary degrees. He was going to call a halt at six only Oxford then came through with ‘the big one’, the letter getting him seriously over-excited. ‘He actually ran upstairs,’ says Monica. And this is a recluse. Fame-seeking, reputation-hugging, he’s about as big a recluse as the late Bubbles Rothermere.

Motion says that institutional rewards for his work annoyed him, but there’s not much evidence of it. Still, to parade in a silly hat, then stand on a platform to hear your virtues recited followed by at least one formal dinner is no fun at all, as Larkin is at pains to point out, particularly when you’ve got sweaty palms and are frightened you’re going to pass out. His account of the Oxford ceremony makes it fun, of course. His new suit looks like ‘a walrus maternity garment’ and the Public Orator’s speech was ‘a bit like a review in Poetry Tyneside’, so he gets by, as ever, on jokes. But if to be celebrated is such a burden why does he bother with it while still managing to suggest that his life is a kind of Grand Refusal? Because he’s a public figure is Motion’s kindly explanation. Because he’s a man is nearer the point.

A crucial text here is ‘The Life with a Hole in it’ (1974):

When I throw hack my head and howl

People (women mostly) say

But you’ve always done what you want

You always get your own way

– A perfectly vile and foul

Inversion of all that’s been.

What the old ratbags mean

Is that I’ve never done what I don’t.

It’s a set-up, though, that repeats itself so regularly in Larkin’s life, Larkin wanting his cake but not wanting it to be thought he enjoys eating it, that it’s hard to go on sympathising as Monica and Maeve (and indeed Motion) are expected to do, as well as any woman who would listen. Not the men, of course. Larkin knows that kind of stuff just bores the chaps so they are fed the jokes, the good ladies his dizziness and sweaty palms, thus endearing him to them because it counts as ‘opening up’.

About the only thing Larkin consistently didn’t do were poetry readings (‘I don’t like going about pretending to be myself’) and television. On the 1982 South Bank Show he allowed his voice to be recorded but refused to appear in person and it’s to Patrick Garland’s credit that he managed to persuade the then virtually unknown Larkin to take part in a 1965 Monitor film, which happily survives. He was interviewed, or at any rate was talked at, by Betjeman and typically, of course, it’s Larkin who comes out of it as the better performer. Like other figures on the right, Paul Johnson, Michael Wharton and the Spectator crowd, Larkin regarded television as the work of the devil, or at any rate the Labour Party, and was as reluctant to be pictured as any primitive tribesman. Silly, I suppose I think this is, and also self-regarding. Hughes has done as little TV as Larkin and not made such a song and dance about it. There is always the danger for a writer of becoming a pundit, or turning into a character, putting on a performance of oneself as Betjeman did. But there was little danger of that with Larkin. He claimed he was nervous of TV because he didn’t want to be recognised, but one appearance on the South Bank Show doesn’t start a stampede in Safeways as other authors could regretfully have told him.

If sticking in Hull seemed a deprivation but wasn’t quite, so were the circumstances in which Larkin chose to live, a top-floor flat in Pearson Park rented from the University and then an ‘utterly undistinguished modern house’ he bought in 1974, ‘not quite the bungalow on the by-pass’ but ‘not the kind of dwelling that is eloquent of the nobility of the human spirit’. It’s tempting to think Larkin sought out these uninspiring places because for him they weren’t uninspiring, and settings appropriate to the kind of poems he wrote. But he seems never to have taken much pleasure in the look of things – furniture, pictures and so on. His quarters weren’t particularly spartan or even Wittgenstein-minimalist (deckchairs and porridge), just dull. The implication of living like this is that a choice has been made, an other of life’s pleasures foregone in the cause of art, part of Larkin’s strategy for a stripped down sort of life, a traveller without luggage.

‘I do believe,’ he wrote to Maeve Brennan, ‘that the happiest way to get through life is to want things and get them; now I don’t believe I’ve ever wanted anything in the sense of a ... Jaguar Mark IX ... I mean, although there’s always plenty of things I couldn’t do with, there’s never been anything I couldn’t do without and in consequence I “have” very little.’ But the truth is, surely, he wasn’t all that interested and if he kept his flat like a dentist’s waiting-room it was because he preferred it that way. He wanted his jazz records after all and he ‘had’ those. In one’s own choosier circumstances it may be that reading of a life like this one feels by implication criticised and got at. And there is with Larkin an air of virtue about it, a sense that a sacrifice has been made. After all Auden’s idea of the cosy was other people’s idea of the squalid but he never implied that living in a shitheap was a precondition of his writing poetry; it just happened to be the way he liked it.

Still, Larkin never wanted to be one of those people with ‘specially-chosen junk,/The good books, the good bed, / And my life, in perfect order’ or indeed to live, as he said practically everyone he knew did, in something called The Old Mill or The Old Forge or The Old Rectory. All of them, I imagine, with prams in the hall. Cyril Connolly’s strictures on this point may have been one of the reasons Larkin claimed The Condemned Playground as his sacred book and which led him, meeting Connolly, uncharacteristically to blurt out: ‘You formed me.’ But if his definition of possessions seems a narrow one (hard to see how he could feel encumbered by a house, say, but not by half a dozen honorary degrees), his version of his life, which is to some extent Motion’s also, was that it he had lived a more cluttered life then Art, ‘that lifted rough tongued bell’, would cease to chime. When it did cease to chime, rather earlier than he’d thought, ten years or so before he died, he went on living as he’d always lived, saying it was all he knew.

Striding down the library in the Monitor film Larkin thought he looked like a rapist. Garland reassured him, but walking by the canal in the same film there is no reassurance; he definitely does. Clad in his doleful raincoat with pebble glasses, cycle-clips and oceanic feet, he bears more than a passing resemblance to Reginald Halliday Christie. Haunting his cemeteries and churchyards he could be on the verge of exposing himself, and whether it’s to a grim, head-scarved wife from Hessle or in a slim volume from Faber and Faber seems a bit of a toss-up. Had his diary survived, that ‘sexual log-book’, one might have learned whether this shy, tormented man ever came close to the dock, the poetry even a safety valve. As it was, lovers on the grass in Pearson Park would catch among the threshing chestnut trees the dull glint of binoculars and on campus errant borrowers, interviewed by the Librarian, found themselves eyed up as well as dressed down.

Day by day your estimation clocks up

Who deserves a smile and who a frown,

And girls you have to tell to pull their socks up

Are those whose pants you’d most like to pull down.

Motion’s hardest task undoubtedly has been to cover, to understand and somehow enlist sympathy for Larkin and his women. Chief among them was his mother, whose joyless marriage put him off the institution long before poetry provided him with the excuse; Monica Jones, lecturer in English at Leicester, whom he first met in 1946 and who was living with him when he died; Maeve Brennan, an assistant librarian at Hull with whom he had a 17-year fling which overlapped with another, begun in 1975, with his long-time secretary at the library, Betty Mackereth. All of them he clubbed with sex, though Maeve was for a long time reluctant to join the clubbed and Betty escaped his notice until, after 17 years as his secretary, there was presumably one of those ‘When-you-take-off-your-glasses-you’re-actually-quite-pretty’ moments. Though the library was the setting for so much of this heavy breathing, propriety seems to have been maintained and there was no slipping down to the stacks for a spot of beef jerky.

Of the three Monica, one feels, could look after herself and though Larkin gave her the runaround over many years she was never in any doubt about the score. ‘He cared,’ she told Motion, ‘a tenth as much about what happened around him as what was happening inside him.’ Betty, too, had him taped and besides had several other strings to her bow, including some spot-welding which she’d picked up in Leeds. It’s only Maeve Brennan, among his later ladies anyway, for whom one feels sorry. Maeve knew nothing of the darker side of his nature, the porn for instance coming as a posthumous revelation as did his affair with Betty. If only for her sake one should be thankful the diaries did not survive. A simpler woman than the other two, she was Larkin’s sweetheart, her love for him romantic and innocent, his for her companionable and protective. Dull you might even say,

If that is what a skilled,

Vigilant, flexible,

Unemphasised, enthralled

Catching of happiness is called.

A fervent Catholic (trust his luck), Maeve took a long time before she would sleep with him, keeping the poet-librarian at arm’s length. Her arms were actually quite hairy, this, Motion says, adding to her attraction. Quite what she will feel when reading this is hard to figure and she’s perhaps even now belting down to Hull’s Tao Clinic. While Maeve held him off the romance flourished but as soon as she does start to sleep with him on a regular basis her days are numbered. Larkin, having made sure of his options with Betty, drops Maeve, who is desolate, and though he sees her every day in the Library and they evolve ‘a distant but friendly relationship’, no proper explanation is ever offered.

There is, though, a lot of other explanation on the way, far too much for this reader, with Monica being pacified about Maeve, Maeve reassured about Monica and Mother given edited versions of them both. And so much of it is in letters. When the Selected Letters came out there was general gratitude that Larkin was old-fashioned enough still to write letters, but there’s not much to be thankful for in his correspondence with Maeve and Monica. ‘One could say,’ wrote Kafka, ‘that all the misfortunes in my life stem from letters ... I have hardly ever been deceived by people, but letters have deceived me without fail ... not other people’s letters, but my own.’ So it is with Larkin, who as a young man took the piss out of all the twaddle he now in middle age writes about ree-lay-shun-ships.

The pity is that these three women never got together to compare notes on their lover, preferably in one of those siderooms in the Library Mrs T’s cuts meant had to be hived off. But then women never do get together except in French comedies. Besides the conference would have had to include the now senile Eva Larkin, whose spectre Larkin detected in all the women he had anything to do with, or had sex to do with. Motion identifies Larkin’s mother as his muse, which I suppose one must take on trust if only out of gratitude to Motion for ploughing through all their correspondence.

What makes one impatient with a lot of the stuff Larkin writes to Monica and Maeve is that it’s plain that what he really wants is just to get his end away on a regular basis and without obligation. ‘Sex is so difficult,’ he complained to Jean Hartley. ‘You ought to be able to get it and pay for it monthly like a laundry bill.’ The impression the public had from the poems was that Larkin had missed out on sex, and this was corroborated by occasional interviews (‘Sexual recreation was a socially remote thing, like baccarat or clog-dancing’). But though Motion calls him a sexually disappointed Eeyore’, in fact he seems to have had a pretty average time, comparing lives with Amis (‘staggering skirmishes / in train, tutorial and telephone booth’) the cause of much of his dissatisfaction. He needed someone to plug him into the fleshpots of Hull, the ‘sensitive and worldly-wise Conquest’ the likeliest candidate, except that Larkin didn’t want Conquest coming to Hull, partly because he was conscious of the homeliness of Maeve. On the other hand, there must have been plenty of ladies who would have been willing to oblige, even in Hull; ready to drop everything and pop up to Pearson Park, sucking off the great poet at least a change from gutting herrings.

I imagine women will be less shocked by the Larkin story, find it not all that different from the norm than will men, who don’t care to see their stratagems mapped out as sedulously as Motion has done with Larkin’s. To will his own discomfort then complain about it, as Larkin persistently does, makes infuriating reading but women see it every day. And if I have a criticism of this book it is that Motion attributes to Larkin the poet faults I would have said were to do with Larkin the man. It’s true Larkin wanted to keep women at a distance, fend off family life because he felt that writing poetry depended on it. But most men regard their life as a poem that women threaten. They may not have two spondees to rub together but they still want to pen their saga untrammelled by life-threatening activities like trailing round Sainsbury’s, emptying the dishwasher or going to the nativity play. Larkin complains to Judy Egerton about Christmas and having to

buy six simple inexpensive presents when there are rather more people about than usual ... No doubt in yours it means seeing your house given over to hordes of mannerless middle-class brats and your good food and drunk vanishing into the quacking tooth-equipped jaws of their alleged parents. Yours is the harder course, I can see. On the other hand, mine is happening to me.

‘And’ (though he doesn’t say this) ‘I’m the poet.’ Motion comments: ‘As in “Self’s the Man”, Larkin here angrily acknowledges his selfishness hoping that by admitting it he will be forgiven.’ ‘Not that old trick!’ wives will say, though sometimes they have to be grateful just for that, and few ordinary husbands would get away with it. But Larkin wasn’t a husband and that he did get away with it was partly because of that and because he had this fall-back position as Great Poet. Monica, Maeve and even Betty took more from him, gave him more rope because this was someone with a line to posterity.

In all this the writer he most resembles – though, ‘falling over backwards to be thought philistine’ (as was said at All Souls), he would hardly relish the comparison – is Kafka. Here is the same looming father and timid, unprotesting mother, a day job meticulously performed with the writing done at night and the same dithering on the brink of marriage with art the likely casualty. Larkin’s letters analysing these difficulties with girls are as wearisome to read as Kafka’s and as inconclusive. Both played games with death, Larkin hiding, Kafka seeking and when they were called in it got them both by the throat.

Like Kafka it was only as a failure that Larkin could be a success. ‘Striving to succeed he had failed; accepting failure he had begun to triumph.’ Not that this dispersed the gloom then or ever. Motion calls him a Parnassian Ron Glum and A.L. Rowse (not usually a fount of common sense) remarks: ‘What the hell was the matter with him? He hadn’t much to complain about. He was tall!’

The publication of the Selected Letters and now the biography is not, I fear, the end of it. This is early days for Larkin plc as there’s a hoard of material still unpublished, the correspondence already printed just a drop in the bucket, and with no widow standing guard packs of postgraduates must already be converging on the grave. May I toss them a bone?

In 1962 Monica Jones bought a holiday cottage at Haydon Bridge, near Hexham in Northumberland. Two up, two down it’s a bleakish spot with the Tyne at the back and the main Newcastle-Carlisle road at the front and in Motion’s account of his visit there to rescue Larkin’s letters it sounds particularly desolate. However Jones and Larkin spent many happy holidays at the cottage and on their first visit in 1962 they

lazed, drank, read, pottered round the village and amused themselves with private games. Soon after the move, for instance, they began systematically defacing a copy of Iris Murdoch’s novel The Flight from the Enchanter, taking it in turns to interpolate salacious remarks and corrupt the text. Many apparently innocent sentences are merely underlined (‘Today it seemed likely to be especially hard’). Many more are altered (‘her lips were parted and he had never seen her eyes so wide open’ becomes ‘Her legs were parted and he had never seen her cunt so wide open’). Many of the numbered chapter-headings are changed (‘Ten’ is assimilated into I Fuck my STENographer). Even the list of books by the same author is changed to include UNDER THE NETher Garments.

Something to look forward to after a breezy day on Hadrian’s Wall or striding across the sands at Lindisfarne this ‘childishly naughty game’ was continued over many years.

As a librarian Larkin must have derived a special pleasure from the defacement of the text but he and Miss Jones were not the first. Two other lovers had been at the same game a year or so earlier only, more daring than our two pranksters, they had borrowed the books they planned to deface from a public library and then, despite the scrutiny of the staff, had managed to smuggle them back onto the shelves. But in 1962 their luck ran out and Joe Orton and Kenneth Halliwell were prosecuted for defacing the property of Islington Borough Council. Was it this case, plentifully written up in the national press, that gave Philip and Monica their wicked idea? Or did he take his cue from the more detailed account of the case published the following year in the Library Association Record, that delightful periodical which was his constant study? It’s another one for Jake Balokowsky.

At 45 Larkin had felt himself ‘periodically washed over by waves of sadness, remorse, fear and all the rest of it, like the automatic flushing of a urinal.’ By 60 the slide towards extinction is unremitting, made helpless by the dead weight of his own self. His life becomes so dark that it takes on a quality of inevitability: when a hedgehog turns up in the garden you know, as you would know in a film, that the creature is doomed. Sure enough he runs over it with the lawnmower and comes running into the house wailing. He had always predicted he would die at 63 as his father did and when he falls ill at 62 it is of the cancer he is most afraid of. He goes into the Nuffield to be operated on, the surgeon telling him he will be a new man ‘when I was quite fond of the old one’. One of the nurses is called Thatcher, another Scargill (‘They wear labels’). A privilege of private medicine is that patients have ready access to drink and it was a bottle of whisky from an unknown friend that is thought to have led him to swallow his own vomit and go into a coma. In a crisis in a private hospital the patient is generally transferred to a National Health unit, in this case the Hull Royal Infirmary, for them to clear up the mess. ‘As usual’ I was piously preparing to write but then I read how Louis MacNeice died. He caught a chill down a pothole in Yorkshire while producing a documentary for the BBC and was taken into University College Hospital. He was accustomed at this time to drinking a bottle of whisky a day but being an NHS patient was not allowed even a sip, whereupon the chill turned to pneumonia and he died, his case almost the exact converse of Larkin’s. Larkin came out of the coma, went home but not to work and returned to hospital a few months later, dying on 2 December 1985.

Fear of death had been the subject of his last major poem, ‘Aubade’, finished in 1977, and when he died it was much quoted and by implication his views endorsed, particularly perhaps the lines

Courage is no good:

It means not scaring others. Being brave

Lets no one off the grave.

Death is no different whined at than withstood.

The poem was read by Harold Pinter at a memorial meeting at Riverside Studios in the following March and I wrote it up in my diary:

3 March 1986

A commemorative programme for Larkin at Riverside Studios, arranged by Blake Morrison. Arrive late as there is heavy rain and the traffic solid, nearly two hours to get from Camden Town to Hammersmith. I am to read with Pinter, who has the beginnings of a moustache he is growing in order to play Goldberg in a TV production of The Birthday Party. My lateness and the state of the traffic occasions some disjointed conversation between us very much in the manner of his plays. I am told this often happens.

Patrick Garland, who is due to compere the programme, is also late so we kick off without him, George Hartley talking about Larkin and the Marvell Press and his early days in Hull. Ordering The Less Deceived no one ever got the title right, asking for ‘Alas! Deceived’, ‘The Lass Deceived’ or ‘The Less Received’ and calling the author Carkin, Lartin, Lackin, Laikin and Lock. I sit in the front row with Blake Morrison, Julian Barnes and Andrew Motion. There are more poems and reminiscences but it’s all a bit thin and jerky. Now Patrick G. arrives, bringing the video of the film he made of Larkin in 1965 but there is further delay because while the machine works there is no sound. Eventually we sit and watch it like a silent film with Patrick giving a commentary and saying how Larkinesque this situation is (which it isn’t particularly) and how when he was stuck in the unending traffic-jam he had felt that was Larkinesque too and how often the word Larkinesque is used and now it’s part of the language. Pinter, whose own adjective is much more often used, remains impassive. Patrick, as always, tells some good stories, including one I hadn’t heard of how Larkin used to cheer himself up by looking in the mirror and saying the line from Rebecca, ‘I am Mrs de Winter now!’

Then Andrew Motion, who is tall elegant and fair, a kind of verse Heseltine, reads his poem on the death of Larkin which ends with his last glimpse of the great man, staring out of the hospital window, his fingers splayed out on the glass, watching as Motion drives away. In the second half Pinter and I are to read with an interlude about the novels by Julian Barnes. Riverside had earlier telephoned to ask what furniture we needed and I had suggested a couple of reading-desks. These have been provided but absurdly with only one microphone so both desks are positioned centre stage, an inch or so apart with the mike between them. This means that when I read Pinter stands silently by and when he reads I do the same. Except that there is a loose board on my side and every time I shift my feet while Pinter is reading there is an audible creak. Were it Stoppard reading or Simon Gray I wouldn’t care a toss: it’s only because it’s Pinter the creak acquires significance and seems somehow meant.

We finish at half-past ten and I go straight to Great Ormond Street where Sam is in Intensive Care. See sick children (and in particular one baby almost hidden under wires and apparatus) and Larkin’s fear of death seems self-indulgent. Sitting there I find myself wondering what would have happened had he worked in a hospital once a week like (dare one say it?) Jimmy Saville.

A propos Pinter I thought it odd that in the Selected Letters almost alone of Larkin’s contemporaries he escaped whipping – given that neither his political views nor his poetry seemed likely to commend him to Larkin. But Pinter is passionate about cricket and, as Motion reveals, sponsored Larkin for the MCC so it’s just a case of the chaps sticking together.

This must have been a hard book to write and I read it with growing admiration for the author and, until his pitiful death, mounting impatience with the subject. Motion, who was a friend of Larkin’s, must have been attended throughout by the thought, by the sound even, of his subject’s sepulchral disclaimers. Without ever having known Larkin I feel, as I think many readers will, that I have lost a friend. I found myself and still find myself not wanting to believe that Larkin was really like this, the unpacking of that ‘really’, which Motion has done, what so much of the poetry is about. The publication of the Selected Letters before the biography was criticised but as a marketing strategy, which is what publishing is about these days, it can’t be faulted. The Letters may sell the Life; the Life, splendid though it is, is unlikely to sell the Letters: few readers coming to the end of this book would want to know more. Different, yes, but not more.

There remain the poems, without which there would be no biography. Reading it I could not see how they would emerge unscathed. But I have read them again and they do, just as with Auden and Hardy, who have taken a similar biographical battering. Auden’s epitaph on Yeats explains why:

Time that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physiqueWorships language and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at their feetTime that with this strange excuse

Pardoned Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.

The black-sailed unfamiliar ship has sailed on, leaving in its wake not a huge birdless silence but an armada both sparkling and intact. Looking at this bright fleet you see there is a man on the jetty, who might be anybody.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.