In the summer of 1946 Nikola Blazevic was in a partisan prison in Mostar awaiting his date with the hangman. Blazevic had been a railway superintendent. His position of local power, as well as the remoteness of his home on the edge of the village of Slipici in south-western Herzegovina, had made him the ideal man for a local Serb to ask to shelter his family. The Serb’s wife and children remained with Blazevic until the end of the war when the Serb returned from the hills with the Partisans. The Serb then denounced Blazevic, a Croat, as a collaborator with the Ustashe.

In this village of 175 families the local management committee had four members – the heads of the only three resident Serbian families and one Croat. The Partisans may have carried the idea of local self-management down from the mountains with the ideological fervour of Marxists, but here power was still yoked to ethnicity. Ironically, a Jew saved Nikola Blazevic’s life. As railway superintendent, Blazevic had used his prior notice of plans for the rounding-up of local Jews to forewarn them. One so notified became the high-ranking Communist commissar who had Blazevic’s sentence cancelled.

In the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia Communism never did more than overlay the centrifugal forces of national feeling. It deep-froze them like a Siberian mammoth, ready for an awful resurrection. With hindsight the idealistic paraphernalia of Yugoslavism seems ludicrous. Yet it had been so heavily invested in diplomatically that when the Federation began to fall apart the response of Western governments was to offer quick-drying cement. Sarajevo’s shell and sniper fire is a rebuke to their caution: a reminder of the fact that unsolved histories don’t go away.

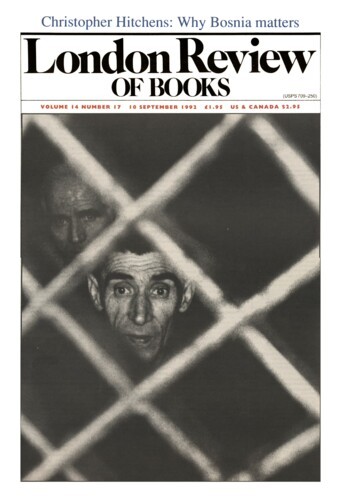

Mladen Ancic lives in the Vojnicko Polje suburb of Sarajevo, an unmoving settlement of scattered high-rises. It’s a front-line suburb, and Ancic and his neighbours dart from corridor to stairwell, like spies, to avoid injury. Their front door is chained shut to prevent the suicidal from presenting themselves to machine-gunners as prey. They climb through small windows into basement living-quarters where pale children who haven’t run down the street in months sit drawing pictures of Bosnian Army soldiers.

Ancic is a historian. He was very proud of his small book-crammed study and apologised for the fact that we had to clamber through the rubble of his mortar-wrecked apartment to get to it. As we stood in the dust, he tried to explain the conflict in terms of Slobodan Milosevic’s opportunistic development from Communist apparatchik to national socialist. Our conversation was hurried by the threat of incoming fire, so the intricacies of an enthusiastic argument were lost. The theme, however, was simple. The Serbian lust for great leaders had experienced the rule of Tito, the Croat, as a happy mutation of their dynastic traditions: under Milosevic, Serbia is once again ready to retreat into the past alter the confused interregnum of the post-Tito rotating presidency.

The cliché about the Balkans is that they produce more history than they can consume. In Sarajevo, parents unload their weapons and give them to their children to play with. In the suburb of Skenderja Mr Dzizo, an art-gallery owner, has given over his viewing space to an exhibition of used munitions – spent bullets, exploded grenades and the tailfins of rockets. Each piece is labelled with data as to its type and calibre and where it fell. Above the recently acquired ordnance hang summery watercolours left over from previous times During the night Mr Dzizo, a soldier in the Bosnian territorial defence, collects more exhibits.

The dead are buried communally, civilians on one side, soldiers on the other. Fresh mounds of earth press up to the boundaries of the graveyard. Plain wooden planks mark each plot, a different shape for each religion, with white plastic lettering spelling out name and life-span. There is a certain rigid beauty to the multiple symmetry of the dates.

The Sarajevans didn’t expect to be troubled by the instability of neighbouring regions. Last March, when buses started to be hijacked to be used as barricades, and armed and hooded men took to the streets, they were surprised. One woman I talked to was going out to a night-club when she found herself marooned in the city centre for three days. Another woman’s two daughters were with their grandmother in the Serbian suburb of Grbavice; she only recovered them in early August in an ethnic swap for three Serb youths that involved a dash across front-line streets. Later some said that their Serbian friends had slipped away unnoticed to Belgrade and the hills just before the trouble began. Most suspected nothing; mingled with the hate, there is still bemusement.

How can you fight an ethnic war in an ethnically-mixed city? Before the war the republic of Bosnia-Herzegovina was 41 per cent Moslem, 31 per cent Serb and 18 per cent Croat with 27 percent of all marriages mixed. Mark Thompson, in A Paper House The Ending of Yugoslavia,* remarks presciently: ‘Insofar as Yugoslavia was ever a multinational state rather than a state comprising many nations, Bosnia-Herzegovina was its truest fragment, the place where the old Yugoslav idea of kindred peoples in harmony stood its best chance to be realised ... if the peoples of this republic ... could not live together in peace, Yugoslavia was past redemption.’ The idea of Yugoslavia was well past redemption by the time Bosnia-Herzegovina splintered like dropped glass.

It is easy to blame it all on the perfidy of the Serbs, and most people do. It is hard to understand the rationale of a group of people who want to expel 28,000 people from their homes in one fell swoop, whose members have reportedly chainsawed refugees to death and who systematically rape, torture and abuse those of other ethnic groups who fall into their power. All this with the expression of aggrieved innocence of a four-year-old smacked for holding his little brother’s head under the bath water. The tone of axiomatic self-justification the Serbs adopt for what they’ve done is truly remarkable. The simplest explanation is that the Serbian leadership and their die-hards have retreated to World War Two, to the reprisal slaughters inflicted on them by the Germans after the Partisan attacks and the original ethnic cleansing of the Ustashe, who sought to convert, kill or expel the majority of Serbs on their territory. Today’s grievance has compacted with yesterday’s, so that there is no distance between an Ustashe slaying in 1943 and a Moslem arguing in a bus queue in 1992.

It’s a process of historical regression that has no end. Serbia’s political creation myth, unlike those of most countries, celebrates a great national defeat: the triumph of the Turks over the Christian army led by Serbia’s Prince Lazar in the battle for Kosovo in 1389. It was a defeat that led to the eclipse of the Serbs for hundreds of years. Thompson has an acute account of the distorting effect on the Serbian national psyche of having as its founding motivation a myth of retribution for cataclysmic defeat. Everyone knows, though it isn’t something people like to talk about, that the struggle for independence of the Albanians of the Kosovo region will be the bloodiest of all the Balkan separatist conflicts, the tenacity of Serbia’s gup there stemming from the centrality of Kosovo in the fable of national humiliation.

In the real world of the late 20th century which the Serbs seem so reluctant to inhabit, living grievances from the Second World War are harder to find than an intact Anderson shelter and the rights and wrongs of Medieval conflict are the stuff of pageants. The Serbs seem incapable even of the forgiveness of for getfulness. What the collapse of Yugoslavia means to the Serbs is the disappearance of their regional predominance; if they are now licking old wounds it is in part at least in order to obscure the power they have had. In the first, ‘royal’ Yugoslavia, between the wars, in a nation that was 60 per cent non-Serb, Serbs held the prime-ministership for 264 out of the 268 months that the state lasted. After the Second World War the Serbs used their status as victims of Ustashe practices to gam political supremacy over the Croats, a moral blackmail in which Tito connived in Order to help stabilise Serbia within the new federal system. The Serbs had also complained after World War One that the Croats and Slovenes gave no thanks for being liberated by Serb agency from the Hapsburg empire. Their ingratitude was punished by their being brought to heel in the same high-handed manner that first raised their hackles.

The Serbian desire to indulge their grievances is symptomatic of their have cake, will eat attitude. The Bosnians haven’t got their effrontery. The presence of the United Nations succours them and suckers them: their public relations status as victims is dependent on a military passivity that close UN supervision encourages but which will do nothing to raise the siege. They don’t have the military strength to ask the UN to leave but are profoundly irritated by the UN’s failure to take sides. Consequently many attempts to achieve serious truces founder in deeply suspicious waters, raising the question: who would benefit most from the murder of UN soldiers or the sabotaging of convoys carrying aid? And who would benefit from any strengthening of the UN mandate and, were it to come, military intervention? For sensible Machiavellian reasons the Bosnians prefer war to stalemate. The last ceasefire, on 19 July, saw the heaviest fighting for weeks begin an hour after the call to lay down arms. The UN refused to say who had first breached the accord. Their new wonder weapon, an advanced Soviet radar system, was not yet in place. It promised a brave new world of crystal images, down to the gunners’ cap badge, of who fired what, where and at whom. This would seriously hinder the continuation of the mayhem by giving the UN firm evidence with which to rap knuckles. Within two days of its arrival the antenna of one of the radar vehicles was badly damaged by a mortar attack at the Airport. The other was positioned with great pride on top of a strategic hill and on its first night of operation received a hit killing one soldier and maiming another.

The UN will continue to give the city a kind of half-life by bringing in supplies. MREs will become the staple diet. Straggling convoys of white UN lorries will form weak land bridges linking the Moslem areas of Bosnia Herzegovina. The pleas of the Bosnian President Alia Izetbegovic to be allowed to reequip his forces will be ignored. The two sides will fight themselves to an impasse and the imposition of the status quo will represent a victory for the Serbs. It’s a pattern formed in the war in Croatia where aggressive Serbian land gain has been rewarded by de facto local independence under UN supervision.

In the dog days of the August heat the city has a beguiling beauty; even the ruins seem to have been there for a very long time. The threat of shelling empties the roads several times a day. Aside from the noises of war, the city looks like the morning after a Biblical exodus. Mid-to-late afternoon is the favourite time for random bombardment. Tank shells falling in distant suburbs send up plumes of smoke into the soft evening sky; it’s too dangerous to go to look at the damage and pain at the bottom of each elegant spiral of dust. Ragtail militiamen and the toy soldiers of the Bosnian Army are the only people who saunter in the streets. Shoppers jog, mentally considering the dismal prospect of dying for the chance to buy a pound of mangy home-grown potatoes. They dart past alleyways posted with signs advertising sniper activity. The wounded hop along breathlessly on crutches.

As ever in besieged cities it’s the black marketeers who prosper. It’s an ebb-and-flow business controlled by a variety of hoodlum militias, each swearing minimal allegiance to one of the ethnic groups. The difficulty of knowing who is firing on whom is compounded by the effect of turf wars. The militias fight for control of the most profitable entry points to the city. Since supply is poor, most of the goods are priced out of people’s reach: $6 for a litre of petrol and $20 for 200 American cigarettes. In the twilight world of the entrepôt villages on the edge of the city, Bosnian soldiers, Serbian policemen and the uglier Croatian volunteer forces gather to cut deals and compare the size to their weapons.

It’s part of the macabre claustrophobia of Sarajevo, where one street corner is deadly and another perfectly safe, that the suburb suffering the heaviest losses, Dobrinja, is beside the one making the ugliest profits. Dobrinja is Sarajevo’s Vukovar, and inspires a similar stubborn pride among its defenders. Soldiers of the Yugoslav National Army, now wearing Serbian badges, bombard the suburb with the best armaments Tito could buy. Inside the suburb the most effective defence is the efforts of soldiers like Edin Hamzic, a 17-year-old platoon commander, who spent three years at military school learning skills he never thought he would need to defend his home town.

It is a further post-Yugoslav irony that both sides’ civilians were taught the rudiments of their military skills at high school. Barbers and butchers could pick up arms, load, aim and fire with the aid of their textbooks. Every Yugoslav teenager was taught the skills of the Partisans; there were practical lessons in weapon calibre and bomb-making and happy school outings to the mountains for live-fire exercises. The compulsory classes in military preparedness have equipped Yugoslav citizens to tear apart the country they were supposed to be learning to protect. The culture of armed readiness, always active in the search for enemies, easily turned on itself. Bosnia’s civil war is the result of that armoured mentality.

In Croatia, where the war froze to a halt in January 1992, it was the cold that lifted fingers from the triggers. Bosnians face the cruellest winter imaginable. At the end of October a bleak, deadening fog descends on Sarajevo, and lasts until the snows begin in December. Then the temperature drops below freezing for three months. The roads will form skating rinks, with no one foolish enough to clear them under shell-lire. Snipers who shoot old ladies hanging out their washing won’t be shy about popping off stumblers in the snow. Unlike petrol, diesel is still relatively easy to buy; it’s being siphoned from winter heating systems. In the autumn, the buses, the Bosnian Army and the boilers will be running on empty. Precious panes of intact glass are held together by a crazy paving of sticky tape. There’ll be little heat to retain. Old doors and the wooden wreckage of buildings will be salvaged for firewood. Fuel scavengers will face stiff competition from coffin manufacturers, who are running out of timber.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.