The daily round in Sarajevo is one of dodging snipers, scrounging for food and water, collecting rumours, visiting morgues and blood-banks and joking heavily about near-misses. The shared experience of being, along with the city’s inhabitants, a sort of dead man on leave makes for levelling of the more joyous and democratic sort, even if foreign writers are marked off from the rest by their flak-jackets and their ability to leave, through the murderous corridor of the Airport road, more or less at will. The friendship and solidarity of Sarajevo’s people will stay with all of us for the rest of our lives and indeed, at the present rate of attrition, it may be something that will only survive in the memory. The combined effect of incessant bombardment with the onset of a Balkan winter may snuff out everything I saw.

On a paved street in the centre of town, near the Eternal Flame (already snuffed out by the lack of fuel) that commemorates the Partisan resistance, is a bakery shop. Eighteen people were killed by a shell that hit a breadline a few weeks ago, and mounds of flowers mark the spot. Shortly after I paid my own visit, another shell fell in exactly the same place, randomly distributing five amputations among a dozen or so children. One of the children had just been released from hospital after suffering injuries in the first ‘incident’. A few hundred yards further on, as I was gingerly approaching the imposing building that houses the National Library of Bosnia, a mortar exploded against its side and persuaded me to put off my researches. All of this became more shocking to me when I went with some Bosnian militiamen to the top of Hum, the only high ground still in the defenders’ grasp. It was amazing, having spent so much time confined in the saucer of land below, to see the city splayed beneath like a rape victim. This view was soon supplanted by an access of outrage. From this perspective, it was so blindingly clear that the Serbian gunners can see exactly what they are doing.

Entering the handsome old Austro-Hungarian edifice that houses the Presidency of Bosnia-Herzegovina, and which absorbed several hits that day, i was panting with relief as I gained the shelter of the vestibule when I saw a poster facing me. Executed in yellow and black, it was a combined logo featuring the Star of David, the Islamic star and crescent, the Roman Catholic cross and the more elaborate cruciform of the Serbian and Bosnian Orthodox. Gens una summus,read the superscription. ‘We are one people’. Here, rendered in iconographic terms, was the defiant remnant of ‘the Yugoslav idea’ (pictures of Tito are still common, in both public and private settings, in Sarajevo). And here, also, was all that was left of internationalism. The display was striking, and not just because it rebuked the primitive mayhem in the immediate vicinity. All across former Yugoslavia, a kind of mass surrender to unreason is taking place, hoisting emblems very different from the Sarajevan.

Across the street from the Zagreb café where I am writing, there is a display of adoring memorabilia, all of it brashly recalling the rule in Croatia of Ante Pavelic and his bestial Ustashe, constituted as a Nazi and Vatican protectorate between 1941 and 1945. Young men in black shirts, and warped older men nostalgic for Fascism, need no longer repress the urge to fling the right arm skyward, or to hear some clerical goon bless their crusade by the guttering of a torch. Their ‘militia’, long used to harass Croatian Serbs, is now heavily engaged in the ‘cleansing’ of Western Herzegovina, in obvious collusion with the Serbian Chetniks to the east and south. Miraculous virgins make their scheduled appearance. Lurid posters show shafts of light touching the pommels of mysterious swords, or blazon the talons of absurd but vicious two-headed eagles. More than a million Serbs attend a frenzied rally, on a battle site at Kosovo where their forebears were humiliated in 1389, and hear former Communists rave in the accents of wounded tribalism. Ancient insignia, totems, feudal coats of arms, talismans, oaths, rituals, icons and regalia jostle to take the field. A society long sunk in political stagnation, but a society nevertheless well across the threshold of modernity, is convulsed: puking up great rancid chunks of undigested barbarism. In this Thirties atmosphere of coloured shirts, weird salutes and licensed sadism, one is driven back to that period’s clearest voice, which spoke of

The Enlightenment driven away,

The habit-forming pain,

Mismanagement and grief:

We must suffer them all again.

Bosnia, and Sarajevo especially, is not so much the most intense and bitter version of the wider conflict, as the heroic exception to it. During respites from the fighting, I was able to speak with detachments of Bosnian volunteers. At every stop, they would point with pride and cheerfulness to their own chests and to those of others, saying: ‘I am Muslim, he is Serb, he is Croat.’ It was the form their propaganda took, but it was also the truth. I met one local commander, Alia Ismet, defending a shattered old people’s home seventy metres from the Serbian front line, who, as well as being a defector from the Yugoslav National Army (YNA), was also an Albanian from Kosovo. There was a Jew among the entrenchment-diggers on Hum Hill, Colonel Jovan Divjak, deputy commander of the Bosnian Army, is a Serb. I shook his hand as he walked, with a Serbo-Croat aide-de-camp named Srdjan Obradovic (‘Obradovic is a multinational name’), through the nervous pedestrians on the edge of the Old City, under intermittent fire at noon. He was unarmed, and popular.

In the Old City itself, you can find a mosque, a synagogue, a Catholic and an Orthodox church within yards of one another. Almost all have been hit savagely from the surrounding hills, though the gunnery is usually accurate enough to spare the Orthodox. (‘Burn it all,’ said General Mladic, the Serb commander whose radio traffic was intercepted and recorded. ‘Let’s fire on the places where there are fewer Serbs,’ replied his more ‘moderate’ deputy, Colonel Sipcic.) The Jewish Museum is badly knocked about and closed, and perhaps one-third of the city’s Jews have fled. So that an ancient community, swelled by refugees from Spain in 1492 and resilient enough to outlive the Ustashe version of the Final Solution, is now threatened with dispersal. Even so, an Israeli Army Radio reporter, who had come hoping to cover the evacuation of Jews, told me that he was very impressed by how many of them wanted to stay on and fight.

The exquisite Gazi Huzref Beg mosque, set in the lovely but vulnerable Muslim quarter of wooden houses and shops, has a crude shell-hole in its minaret, and its courtyard garden is growing unkempt. The mosques, very important in the siege for their access to antique stone cisterns or sadrivan, used for ablution before prayer, have found even these old wells drying up under the assault. And thirst is a fiercer enemy even than hunger.

To speak of ‘quarters’ is not to speak of ghettoes, or at least not yet. A good estimate puts the proportion of mixed marriages here at one in three; a figure confirmed by anecdote and observation. So to try and make Bosnia ‘uniform’ in point of confession or‘ethnicity’ is not to put it together but to tear it apart. To call this dirty scheme by the name of ‘cleansing’ is to do grotesque violence to both language and society.

To turn from the greatest poet of the Thirties to its greatest essayist, we find that Leon Trotsky wrote in 1933 in Harper’s magazine that the idea of the necessity of re-adapting the state frontiers of Europe to the frontiers of its races is one of those reactionary Utopias with which the National Socialist programme is stuffed ... A shifting of the internal frontiers by a few dozen or hundreds of miles in one direction or another would, without changing much of anything, involve a number of human victims exceeding the population of the disputed zone.’

The 2,400,000 refugees and the numberless dead already outweigh the populations of the various ‘corridors’ by which Serbian and Croatian nationalists seek to purify their own states and to dismember Bosnia. As before, their ‘nationalism’ has its counterpart in the axiomatic resort to partition by certain ‘non-interventionist statesmen’. When Lord Carrington, obviously bored with the entire thing, called (if anything so languid and vapid can be termed a call) for ‘cantonisation’, then the Serbian puppet in Bosnia, Radovan Karadzic, and the Croatian client in Bosnia, Mate Boban, both make a little holiday in their hearts. The British Foreign Office’s favourite fetish has triumphed again! After Ireland, India, Palestine, the Sudetenland and Cyprus, partition – or ghettoisation – ceases to look like coincidence. Cantons by all means! They won’t take long for either of us to cleanse! The consequence at ground level is not unlike what I saw near the town of Novska, on the Croatia-Bosnia border. An immaculate contingent of Jordanian UN soldiers was politely concealing its shock at the tribal and atavistic brutality of this war between the whites. It had done its task of separating and disarming the local combatants. But now here came six busloads of Bosnian Muslim refugees, many of them injured, who had taken the worst that Christian Europe could throw at them and who were bewildered to find themselves under the care of a scrupulous Hashemite chivalry. Croatia wants no part of these victims of ‘Serbian terror’: a terror that it denounced only when it was directed at Catholics.

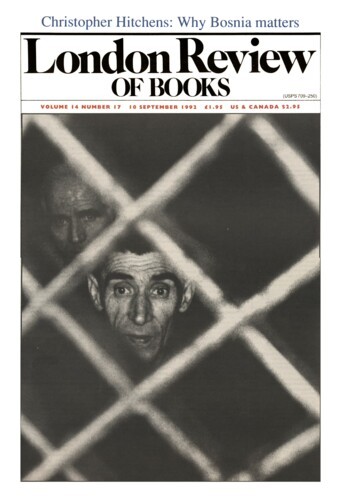

Very few journalists who employ the expression ‘ethnic cleansing’ know where it originated, and its easy one-sided usage has maddened the already paranoid Serbs. Jose Maria Mendeluce, the exemplary Basque who came here from Kurdistan as the special envoy of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, told me he thought he had coined the term himself (though he blushed to recall he had used the word ‘cleaning’). But of course there is no ethnic difference between the Slavs, any more than there was between Swift’s Big-Endians and Little-Endians. Nor is there a linguistic difference. And religion has not yet succeeded (though it has often failed) in defining a nationality. So ‘cultural cleansing’ might cover the facts of the case if it did not sound more ludicrous than homicidal. At all events, we know that a reporter for Belgrade TV described the gutted, conquered Bosnian city of Zvornik with the single word cist (‘clean’) after it fell in April. And the unhygienic militia which did the job, the self-described Chetniks of the warlord Voytislav Seselj, also freely used the happy expression. The ‘camps’ which were the inescapable minor counterpart of this process have at least served to concentrate the flickering European and American mind upon a fading but potent memory, though the intercuts with Belsen and Auschwitz used by some of the media go to show not that people learn from history but that they resolutely decline to do so, and instead plunder it for facile images.

Who, if anyone, plays the part of the Reich in this nightmare? Srmt Fasizmu! Sloboda Narodu!(‘Death to Fascism! Freedom to the People!’) say the wall-posters of the Sarajevo Commune. They don’t say which fascism in particular. And Mr Milosevic, the Serbian demagogue, is the notional heir to a vestigial Socialist Party and a lavishly accoutred People’s Army, paid for out of the historic tax levies of Croats, Bosnians and Macedonians but now the exclusive property of the Serbian-dominated rump state. In order to understand the Serbian political psyche. I had to visit, and indirectly to loot, two significant museums.

The first of these was the Gavrilo Princip Museum in Sarajevo, which stands by the bridge of the same name on the Miljacka River and is normally enfiladed by Serbian gunfire. Its wrecked appearance is deceptive nonetheless, because although it has taken a round or two of Serbian mortaring, its destruction was wrought by enraged Sarajevan citizens. Gavrilo Princip, who stood quivering on this corner on 27 June 1914 waiting to fire the shot heard round the world at the fat target of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand, was a member of the Young Bosnia organisation which yearned and burned for the fusion of Bosnia with Serbia. No cause could be less fashionable in Sarajevo today: the crowd had even gone to the length of digging up the famous two ‘foot-prints’ sunk in the pavement to memorialise Princip’s supposed stance. Until recently, this was the museum of the ‘national hero’, and bore witness that Serbia, in alliance with Russia, was the guarantor of all Slavs. Princip appears to have chosen the date to coincide with the exact anniversary of the Serbian defeat at Kosovo in 1389, which testifies to the power of aggrieved memory and to the Serbian conviction that they are the victims of regional history: under-appreciated by those for whom they have sacrificed.

The second museum I visited was the site of the Jasenovac concentration camp, a real one this time, where during the Nazi period some hundreds of thousands of Serbs and Jews, as well as gypsies and Croatian Communists, were slaughtered by the Ustashe regime of Ante Pavelic. No German even supervised this cleansing, which was an enthusiastic all-volunteer effort to rival Latvia or the Ukraine. Here is the Serbian Babi Yar, a piercing wound in the heart. It sits on a broad, handsome field where the Rivers Sava and Una converge. During the appalling Serb-Croat combat of last year, it was occupied for a while by Croatian forces, These methodically trashed the museum and the exhibits, and left only the huge, ominous mounds that mark the mass graves. As in Sarajevo, I was able to salvage a few gruesome photographs from the debris. My Serbian guide, a friendly metalworker named Mile Trkulja, told me: ‘The world blames the Serbs for everything, but nobody writes about Jasenovac’.

In other words, it is not so very difficult for the Serbs to become that most toxic and volatile of all things – a self-pitying majority. Faced by the mass expulsions of Serbs from the new Croatia, and laden with historical resentment, many of them fell for the oldest and easiest option, exemplified by the Serbian motto: ‘Only Solidarity Can Save the Serbs’ Here was a Versailles mentality, replete with defeat and fear on the part of the stronger side. In an astounding speech, given at the last Congress of Serbian Intellectuals to be held in Sarajevo, as recently as March of this year, the Serbian academic Milorad Ekmecic phrased this mentality in direct speech (my italics):

The Serbian people does not want a state determined by the interests of the great powers and of European Catholic clericalism, but one which emerges from the ethnic and historical right possessed by every people in the world. In the history of the world, only the Jews have paid a higher price for their freedom than the Serbs. Because of their losses in war, and because of massacres, the most numerous people in Yugoslavia, the Serbs, have in Bosnia-Herzevogina fallen to second place, and today our policy and our general behaviour carry within themselves the invisible stamp of a struggle for biological survival. Fear governs us ... Therefore the internal division of Bosnia-Herzegovina into three national parts is the minimal guarantee for the maintenance by Serbian and Croatian peoples of a partial unity with their national homes.

Under the Milosevic dispensation, this combined pathology of superiority/inferiority has become the equivalent of state dogma. With dismaying speed, and by a gruesome metamorphosis, the ideology of the Partisans and of one Yugoslavia has mutated into yells for a Greater Serbia, and the army devised by Tito for defence against foreign intervention has been turned loose, with various militias, against civilians and open cities. You could, without stretching things much, describe this hybrid as ‘national socialism’. (The man who commanded the now-notorious POW camp at Omarska, unearthed last month, was born in Jasenovac. ‘Those to whom evil is done ... ’)

Yet was it not true that Croatia, too, had a fascist ideology and a contempt for Serbian rights? By all means it was true. President Franjo Tudjman does not quite affirm the Ustashe tradition, and can usually contrive to keep his right arm by his side, but he did adopt a near-replica of the Pavelic symbol for his national flag, and he did write an incautious revisionist book which said the Jasenovac camp had really killed very few Serbs and, in any case, was largely run by Jews! He coupled this with a campaign of harassment, if one can state it mildly, against the 750,000 Serbs living in Croatia, 200,000 of whom have ‘relocated’. Finally, he solicited the support of Germany, Austria and Italy, thus bringing into being the very geopolitical alliance that every Serb is taught by history to fear.

Serbs were never persecuted in Bosnia, however. Nor were Croats. But now Serbian and Croatian irredentists are allied in a sort of Molotov-Ribbentrop pact against a defenceless neighbour. (Ekmecic was wrong. There will be two Bosnias, not three, and he knows it.) Each uses its ‘Sudeten’ minorities to establish ‘pure’ mini-states which will in time demand fusion with the mother and fatherlands. The Serbs have proclaimed republics in Croatian Krajina, and in Bosnia. The turn of Albanian Kosovo is probably not far behind. Meanwhile the Croats have begun the annexation of Western Herzegovina on Bosnian soil. There is no guarantee at all that this infinite, narcissistic subdivision will not pursue itself across international frontiers (Greece and Bulgaria in the case of Macedonia, and Albania in the case of Kosovo) and attract the ‘protective’ interest of outside powers like Turkey, armed with Nato weapons. But then, that’ s what Balkanisation is supposed to mean.

There is no special need to romanticise the Muslim majority of Bosnia. But they have contrived to evolve a culture which expresses the plural and tolerant side of the Ottoman tradition – some of this subtle and diverse character can be found in the stories of Ivo Andric, Yugoslavia’s Nobel Laureate – and they have no designs on the territory or identity of others. The Bosnian president, Alija Izet-begovic, is a practising Muslim, which makes him the exception rather than the rule among his countrymen. I have read his book, Islam between East and West, a vaguely eccentric work which shows an almost pedantic fidelity to ideas of symbiosis between the three monotheisms and to the humanist tradition of social reform. In the surreal atmosphere of a press conference under shellfire, I asked Izetbegovic, who is accused by both Serbs and Croats of wanting to proclaim a fundamentalist republic, what he thought of the fatwah condemning Salman Rushdie. He gave the reply of the moderate Muslim, saying that he did not like and had not read the book but could not agree to violence against the author.

It is possible to meet the occasional Bosnian Muslim fanatic, and it is true that some of them made an attempt to setquester some Sarajevo Serbs in a football stadium. But that action was swiftly Hopped, and roundly denounced in the newspaper Oslobodenje (‘Liberation’). None of the Bosnian Serbs I met had any complaint of cruelty or discrimination, and where they had heard of isolated cases they swiftly reminded me that is was the Serbian forces who had stormed across the River Drina, and not the other way about, thus breaching a centuries old recognition of the integrity of the Bosnian patch-work. If, however, that patchwork is ripped to shreds and replaced with an apartheid of confessional Bantustans, those who talk ominously of Muslim fundamentalism may get their wish, or their pretext.

During the Tito and post-Tito years, one used to read Praxis, a journal of secular intellectuals, in order to find out what impended in Yugoslavia. Suppressed by the regime in 1975, the magazine continued to publish as Praxis International under the aegis of Jürgen Habermas and other European and American sympathisers. Since the push for Greater Serbia began to ignite every other micronationalism in the region, I had not heard the voice of Praxis above the snarlings and the detonations. But in Zagreb I did manage to find the oldest and the youngest member of this apparently irrelevant collective.

Professor Rudi Supek is a veteran by any definition. For his work in organising resistance among Yugoslav workers in Nazi-occupied France he was sent to Buchenwald and is now the last survivor of that camp’s successful Liberation Committee. He left the Communist Party when Tito broke with Stalin in 1948 (not a bad year, considering) and now tries to keep alive the ideas of secularism and internationalism in a Croatia which has grown hostile again. ‘My family is an old Croat family but I have no choice but to say I am still Yugoslav. In Buchenwald I was the chosen representative of Serbs, Bosnians and Croats, and they were Yugoslav in a way that I cannot betray’.

Zarko Puhovski, the youngest Praxis adherent, teaches at Zagreb University in political philosophy and bears with stoicism the antisemitic cracks which come his way as the son of a Jewish mother and a Croatian Communist father who did hard time in Jasenovac. ‘If you say you are a Croatian atheist, given that there are no ethnic or linguistic differences’, he told me, ‘the next question is: “How do you know you are not a Serb?’’ For both of these men, the contest with their ‘own’’ chauvinism was the deciding and defining one. And for both of them, the defence of multinational Bosnia was the crux.

‘Both the Chetniks and the Ustashe should be told to keep out of Bosnia,’ said Supek. ‘The fascists on both sides must be defeated and disarmed. If this needs an international protectorate, it should be provided.’ ‘The embargo on arms to “both sides” is pure hypo crisy’, said Puhovski, ‘The Bosnians need arms to defend themselves, and the YNA has appropriated to itself the weapons that used to belong to everybody.’ (This, by the way, echoed the street opinion in Sarajevo, which roundly opposed the idea of foreign troops on Bosnian soil but witheringly criticised the moral equivalence which the great powers are using as a hand-cleansing alibi.)

Post-Communist Europe is hesitating on the brink of its own version of Balkanisation, and Yugoslavia gives an inkling of what could lie ahead for more than one region, to say noth ing of more than one culture. Bosnia mat ters, because it has chosen to defend not just its own self-determination but the values of multi-cultural,long-evolved and mutually fruitful cohabitation. Not since Andalusia has Europe owed so much to a synthesis, which also stands as a perfect rebuke to the cynical collusion between apparently ‘warring’ fanatics.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.