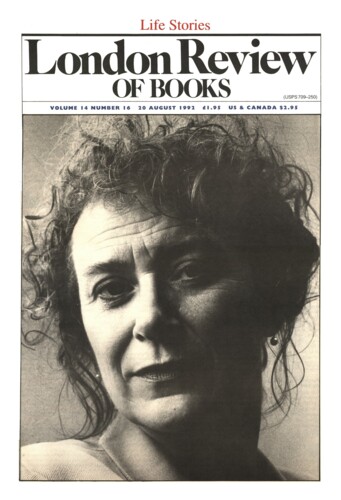

What do a story written by primary schoolchildren, a study of 19th-century policing, a biography of Margaret McMillan and an account of a working-class childhood in South London in the Fifties have in common? They give some idea of the range of Past Tenses, a selection from Carolyn Steedman’s prolific output of books and articles during the last ten years. Steedman is an academic – she remarks wryly on the Universities Funding Council as a source of the pressure she feels to write and publish – but her research and her theoretical insights are interfused with the obsessions and narrative quirks of an imaginative writer. One could quite easily see the series of ‘life stories’ summarised in Past Tenses as the oeuvre, not of the educationalist and historian that Steedman is usually taken to be, but of a new sort of storyteller, perhaps even a new sort of novelist.

This is to suggest that Steedman deserves an audience wider than the one usually reserved for research and theory, even in the interdisciplinary area of women’s studies. She has, already, reached such an audience with her autobiographical account of her own and her mother’s childhoods. Landscape for a Good Woman (1986). At once passionate, meditative and intensely self-reflexive, Landscape set out to challenge the sentimental and moralistic pictures of working-class community associated with Richard Hoggart, Jeremy Seabrook and Steedman’s particular mentor, Raymond Williams. The childhood Steedman described was not cosy and hospitable but lonely, introverted and largely joyless. Her mother, a Lancashire weaver’s daughter, had fought against marginality and deprivation by moving to London, becoming a professional manicurist, and bringing up her children on a healthy diet of salads and watercress – all strategies which failed disastrously, estranging her from her family and her neighbours. Both Carolyn and her sister rejected their mother as soon as they became adults. Years later, the mother’s death brought to light (among other shocks) the carefully hidden fact of their illegitimacy. Even the Registrar of Births had been lied to, a ‘discovery about the verisimilitude of documents’ that continues to worry Steedman.

‘Is it to be wondered that married sons and daughters take a few years to wean themselves from their mother’s hearth?’ asked Hoggart in one of the more unctuous passages of The Uses of Literacy. Steedman has spent considerable energy demolishing this kind of writing, though she is clear that, as a model or utopia of family life, it is more desirable than her own childhood landscape of dreaming, envy and bitterness. Yet what links all these accounts, including her own, is the desire to rediscover a lost childhood – in Steedman’s case, perhaps, the moments of happiness before things began to go wrong. There may be, as she says, an element of psychoanalytic transference in all historical writing. But the story of one’s own childhood is peculiarly vulnerable to the slippage between history and ‘case-history’, in which fantasy and distortion are the raw material, and are no less valuable than documented fact. The role of reconstruction and reinterpretation are foregrounded in Steedman’s autobiographical account, which begins with a dream and ends, more or less, with a political message.

Steedman’s life-story strongly recalls some earlier accounts of deprived childhood, which predate the Welfare State period when Hoggart and Seabrook were writing, and which would not necessarily be construed as working-class. Landscape for a Good Woman is professedly indebted to Kathleen Woodward’s Jipping Street (1928), the life-story of a journalist who became the biographer and confidante of Queen Mary. Jipping Street transposed the scene of its author’s childhood from Peckham to Bermondsey in order to give it a more authentically working-class flavour (shades of John Major?). A generation earlier, H.G. Wells grew up in a basement kitchen with a mother as discontented as Steedman’s and Woodward’s, a mother who abandoned the domestic hearth, and forced her younger son out into the world as a draper’s apprentice the moment she found an opportunity to become resident housekeeper to the widowed Lady Fetherstonhaugh (who had once been a dairymaid). In Tono-Bungay, Wells has a wickedly funny description of teatime in the housekeeper’s room at Bladesover House, based on one of his rare visits to his mother. Between Wells’s snobbish upper servants and Steedman’s manicurist in Mayfair serving rich ladies, we may measure some of the varieties of what is now called ‘working-class Conservatism’.

Tono-Bungay has the classic form of the autobiographical novel. Wells’s narrator sits at the tea-table seething with impatience, a fidgety adolescent who gets told off for kicking his chair. We know he is leaving, and the novel is his story of rebellion against ‘Blades-over House, and my Mother; and the Constitution of Society’ (to quote the title of the first chapter). But Landscape for a Good Woman refuses this classic form, presenting its author as the good (though oppressed) child and avoiding any description of the act of breaking away. The emotional centre of the book is not breaking away, but the tension and the conflict of the movement back, the writerly recovery of the lost childhood. One can see why the established forms of fiction lack narrative models for what Steedman wishes to do. Few novels in the tradition are really concerned with childhood, except as a prelude to, and preparation for, adolescence and widening horizons. Some that do purport to be so concerned, like Swann’s Way and (arguably) What Maisie Knew, turn out to be about something else entirely. In Past Tenses Steedman confesses to a fondness for Richardson’s Pamela, with its comical, literate heroine ‘of the poorer sort’, but Pamela too is a breaking-away narrative.

Carolyn Steedman’s mother played her cards badly and lived a life of unfulfilled desires; Pamela is the virtuous girl who gets what she wants. Steedman is alone among present-day readers in speaking affectionately of Richardson’s third and fourth volumes, which are simply omitted from the current Penguin edition. Here the story of a seduction gives place to the annals of the bourgeois housewife, with Pamela meticulously describing her adventures as a mother and instructor of small children. Steedman herself worked for some years as a primary teacher, and she writes feelingly and with some anger that ‘all those who have anything to do with children have low status in our culture.’ Her biography of Margaret McMillan argues that the experience and ideology of middle-class mothering from Richardson onwards profoundly influenced modern educational theory, which entrusted the state primary teacher with the task of making good the deficiencies of working-class child-rearing.

Just how and why Steedman became a dedicated primary teacher is a story merely hinted at in Landscape for a Good Woman. Nevertheless, her notion of narrative as case-history is based partly on the stories her pupils invented, and which she published in The Tidy House. There are many other stories, too, in Landscape, drawn in by imaginative association rather than by any very rigorous notions of experiential continuity or logical analogy. In Past Tenses the same set of stories turns up in other contexts as well. One of her favourite stories – told here in the form in which she gave it to an academic conference – is that of the eight-year-old watercress-seller interviewed by Henry Mayhew in London Labour and the London Poor. The watercress girl was a ‘good and helpful child, who eased her mother’s life’, much as the young Steedman tried to be. At roughly the same age as Mayhew’s informant, Steedman was told off by her mother for lingering at school when she should have been going down to the shops to buy watercress for tea. This presumably explains the disturbing and faintly embarrassing passage in her public lecture, in which she describes Mayhew’s figure as her ‘fantasy child’: ‘the Little Watercress Girl is what I want: the past, which is lost and which I cannot have: my own childhood.’ But she knows that she may as easily be mistaken for the prurient Mayhew, the social investigator who encountered the watercress girl on the streets, and then went back to his study to write about her.

Mayhew was puzzled whether to address the watercress girl as a child or a woman; the modern reader, however, must ponder the fact that the children he spoke to ‘on the streets’ (a significantly gendered phrase) were nearly all female. For Steedman this points towards a wider history, in which the figure of the young girl in the 19th century became emblematic of childhood itself, and especially of deprived childhood. One reason for this, I suspect, is that in the shadow of Victorian values such as ‘self-help’, any able-bodied man who failed to rise by his bootstraps was likely to be found guilty of some character defect. Feminine weakness made the girl or child-woman peculiarly suited to the role of victim. The tragic heroines of naturalistic novels are more easily represented as the playthings of circumstance, and therefore as representatives of the human condition, than men would be. Moreover, their suffering has a romantic and erotic charge.

This process of the ‘feminisation’ of experience is rich in historical and cultural specificity, but it also exemplifies the element of transference in our relationships to history and to fiction. The watercress girl documented by Mayhew becomes a dream figure, a figment of the romance of the urban poor. In Past Tenses Steedman reflects ruefully that she seems incapable of saying anything ‘without messing with some other story, some other person’s narrative’. Conventionally one would think of the watercress girl as a starting-point for the present-day historical novel, for a discourse of imagined situations and invented characters, rather than for the autobiographical meditations in which Steedman engages.

We have been told often enough why the novel matters, but do the boundaries separating it from history and autobiography still matter? Steedman reflects a good deal on these boundaries, and says that she wants to be understood as contributing to a shared historical consciousness, or what she calls a ‘community of cognition’. The category of cognitions must include the critical reading of fictions and case-histories as well as what passes for historical fact. In reading about the idea of lost childhood, we should begin with the ambiguity of the phrase: the childhood I have lost is either what I once had, or what I never had, or an imaginative fiction (such as T.S. Eliot’s rose-garden) compounding the two. Whatever the ratio of memory to invention, the result is necessarily a case-history which falsifies, just as fiction does, but which leads towards the truth to the extent to which its falsification can be seen through and allowed for.

Distortion and falsification in the case of autobiographical writings are frequently alleged, but notoriously difficult to prove. (Think of the arguments over whether or not George Orwell ever shot an elephant, or witnessed a hanging, or got beaten at school for wetting his bed.) One may, however, properly and tactfully point to the light and shade, the emphases and suppressions in any autobiographical landscape. In Steedman’s case the stones of breaking away of puberty and its aftermath, and of the final estrangement from her mother’s hearth are passed over as quickly as possible. She remarks that the author of Jipping Street ‘shrank from sexual knowledge’, and says something similar of Margaret McMillan; in her own case she writes of myopia and headaches. For all the stories she tells openly, in the very individual forms that she has created, there are others that seem to be present through a form of subterfuge. Past Tenses looks back with a well-earned pride over what is a remarkably rounded and self-contained body of work, yet in future books one may be sure that Steedman will both extend and subvert its narrative boundaries.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.