In Melbourne prison, Australia, in November 1906, Tom Mann, socialist agitator, aged 50, was visited by J. Ramsay MacDonald, newly-elected Labour MP for Leicester, aged 40. Nothing is recorded of what was said. Macdonald may have expressed his enthusiasm at the advance of the Labour Party. He had trebled his vote at Leicester, and the Party now had 29 MPs. He may well have looked forward to the ‘century of the Great Hope’ which so many new social democrats believed was certain to follow the triumph of socialist ideas at the polls. Tom Mann, who was in prison for ‘obstructing the police’ by speaking at a socialist meeting in a Melbourne suburb, would certainly have put his visitors at their case. He had a natural gaiety about him and an unquenchable sense of humour, especially when in prison. But it is unlikely that Ramsay MacDonald left without at least one of Tom Mann’s celebrated jibes at Parliament ringing in his ears. At any rate, Mann did not forget the visit.

Twenty-six years later, at the ripe old age of 76, he was in prison again – in Brixton, London – for refusing to be bound over after a National Unemployed Workers’ Movement demonstration. The prime minister at the head of the right-wing National Government of the day was J. Ramsay MacDonald. Tom Mann started his socialist life, as MacDonald did, by assuming that socialist goals could be achieved through the vote. He was growing up as that vote was quickly extended to the majority of British men, and he started his political life as North-East organiser and agitator for the Social Democratic Federation. It was cruel work, and he found the narrow, sectarian approach of the SDF unconvincing and unattractive. Before long he was on his way south to take part in the event which shaped the rest of his long political life – the Great Dock Strike of 1889. This strike was won not, as most Socialists thought likely, by the ‘aristocracy’ of labour, the men (like Tom Mann) who had served their time, and read Shakespeare in the local institute libraries, but by the ‘lowest of the low’, the impoverished casual labourers of the London docks. Tom Mann revelled in this activity, which kept him up night and day for the whole month of the strike. He was by a long way the strike’s outstanding leader, rushing from place to place, calling the workers onto the streets to raise their spirits with jokes, demonstrations and stunts. The dockers’ victory and its consequence, an astounding surge in the self-confidence of the British working class, was a lesson to Tom Mann all his life. He saw how the workers, in the course of their own action, changed from hopeless down-and-outs into enthusiastic, disciplined and rational human beings. It was a change, he reckoned, worth fighting for.

Tom Mann became a syndicalist. He placed his faith in the ability of the working class through strikes and agitation to shake the employers’ economic system to its foundations. A new socialist society could only be built, he argued, by stoking up workers’ organisations and exerting power until capitalism could not continue any longer. This approach made him extremely unpopular not just with employers and governments, but also with the new middle-class socialists. Beatrice Webb held a sumptuous dinner to celebrate the first ILP election victories in 1895. One of the guests was Tom Mann, who made his position quite plain. Mrs Webb was indignant: ‘He is possessed,’ she wrote, ‘with the idea of a “church” or a body of men all professing the same creed and all working in exact uniformity to the same end... And, as Shaw remarked, he is deteriorating. This stumping the country, talking abstractions and raving emotions, is not good for a man’s judgment, and the perpetual excitement leads, among other things, to too much whisky.’ There were things even worse than whisky lying in wait for this monster raving loony. Two years later, Tom Mann was flung out of the ILP because it was rumoured he was going round with a woman who was not his wife. It was true, as he readily admitted. He left his wife, and went to live with Elsie Harker in happiness and love for nearly half a century.

Tom Mann was not deteriorating. All this stumping the country for socialism was so exhilarating that he determined to stump some other countries too. All his life he was a committed internationalist, declaring that the basic needs and aspirations of ordinary people were the same the whole world over. When MacDonald met him in Melbourne, he was in the middle of the most ferocious agitation, which laid the foundation stone for strong trade-unionism in Australia for the rest of this century. During all his long life, Tom Mann travelled ceaselessly, especially in the old Commonwealth – from South Africa, where, rather to the distaste of the ‘mature’ labour movement there, he spoke up for the blacks, to Canada, where he spoke up for the French, to Russia, where he interceded with Lenin for imprisoned anarchists, and even to China. He always managed to get back for the big labour upheavals in Britain. In 1911, his base was Liverpool, where he became the leader of another great shipping and dock strike. In five weeks the National Union of Dock Labourers, which was based in Liverpool, grew in membership from eight thousand to 26,000. ‘The whole of Liverpool,’ Mr Tsuzuki tells us, ‘was like an armed camp.’ For printing in his new paper, the Syndicalist, an appeal to soldiers not to shoot at striking workers, Mann was sent for two months to Strangeways prison. ‘Don’t worry, Mam,’ he wrote to Elsie. ‘This won’t hurt me and I shall be as right as pie.’

Explaining the basis of his syndicalism in a pamphlet written with his friend and fellow dock-strike leader Ben Tillett in 1890, Mann said: ‘The political machine will fall into our hands as a matter of course as soon as the educational work has been done in our labour organisations.’ Politics, it followed, was trivial enough to be left to the Parliamentarians. The view served him well through the labour ‘high’ of 1911 and 1912. It was not so valuable in 1914. Returning from South Africa, Tom Mann reflected: ‘I extremely regret that the workers of the world are at one another’s throats.’ A year later, however, he was writing: ‘I am really of the opinion that the war ought and must be fought out.’ For the first three years of the war he buried himself in simple trade-union work, cutting himself off from the anti-war activists, especially on the Clyde. Though he never became a warmonger like his friend Tillett, he did not oppose the war. This cannot have been for lack of courage – Tom Mann never shirked any battle he believed in. His apolitical syndicalism left him without independent political answers when the workers, on whose industrial strength he depended exclusively, stampeded to the colours.

After the war, his old energy revived. After a short term as general secretary of the engineering workers’ union (which was merged in that time to become the AEU, as it is known today), he threw himself into the Red International Labour Union, which was founded in Moscow in 1921. Lenin’s aim was to set up revolutionary trade unions to counter the ‘reformist’ trade unions which were being set up in the capitalist world. This policy led in Britain to the National Minority Movement, which flourished in British trade unions between 1924 and 1926. Nearly a million trade-unionists were represented at the NMM conference in March 1926. Its policy was unrelieved industrial militancy, and it played a considerable part in the early success of the ‘triple alliance’ of miners, railwaymen and transport workers. When the General Strike of 1926 was defeated, however, the NMM quickly withered away.

Tom Mann joined the Communist Party soon after it was formed in 1922, but he never played a central role in Party activities. He was not elected to the Central Committee until 1937, when he was 81. He always preferred industrial agitation to political organisation. He supported the Russian Revolution throughout the Twenties and by the time Stalin started to extirpate every revolutionary vestige of that revolution, Tom was an old man. In the late Twenties he was appointed to a three-man RILU commission to China. His two companions were Earl Russell Browder, a young American Communist, and Jacques Doriot, one of the most popular Communist leaders in France. The three men were sent to ‘monitor’ the Chinese workers’ revolution, which had seized the centre of many of the big cities. The commission was in China during the crucial weeks of 1927, and saw and faithfully reported the terrible defeat and massacre of the Chinese workers. They did not see and did not report that the defeat was plotted in the Kremlin, and that the new Stalinist foreign policy (‘socialism in one country’) condemned the fighting Chinese Communists to the most horrible fate. It is a strange and sobering experience to read the reports of these three devoted Communists as they chronicle the disaster for which their beloved Stalin was chiefly responsible. Once more the abstentionism inherent in the syndicalist case – the abandonment of ‘difficult’ political decisions to ‘them upstairs’ had blinded Tom Mann to the cause of this most awful horror.

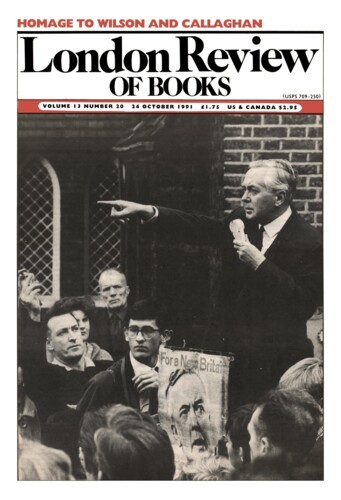

Tom Mann’s particular genius was speaking in public. No one can test this out, because little if any of him is on film – but Tom Mann was probably the finest public speaker in British labour history. Like many good speakers, he yearned in his youth to be an actor, and always loved the theatre. His supreme gift was his humour. My witness is Harry McShane, who died in 1988 aged 97 after a lifetime’s agitation not unlike Tom Mann’s. Harry heard them all – Hyndman, MacLean, Grayson, Wheatley, Cook, Maxton, Bevan, Pollitt – yes, even MacDonald. ‘None of them was a patch on Tom Mann,’ he would say. He described a meeting in Mansfield in which Mann ridiculed the Parliamentary aspirations of the day. ‘He fell on his knees on the front of the stage, imploring Parliament, beseeching, begging Parliament to do the job. We were all in stitches, screaming with laughter.’ Harry also told me about ‘this Japanese chap who’s written a very good book on Hyndman, and another on Eleanor Marx. He’s been asking about Tom Mann and the New Unionists. He’s writing a book about it, I hear. Make sure you get it when it comes out.’

Chushichi Tsuzuki probably set out to write a book about the three dock-strike leaders, Tom Mann, Ben Tillett and John Burns. At some stage, he presumably plumped lor Mann because he is so much more consistent than the other two. Burns ended up in the Liberal Government and Tillett became a TUC mandarin and a shameless spokesman for the collaborationist Mond-Turner proposals in the late Twenties. But there is still too much Tillett and Burns in the book, not enough Tom Mann. In these days when (as in the 1870s and early 1880s) everyone says that the working class doesn’t exist and socialism is a dangerous fantasy, we could have done with much more of Tom Mann’s experience in both matters. His life should have been dovetailed more into his times, his syndicalism woven more carefully into the rise and fall of working-class confidence, and his submission to Russian foreign policy more carefully and critically explained. All that said, we’ve got a marvellous glimpse of a British working-class hero from a professor of International Relations at the International University of Japan, Niigata-Urasa. Few things would have pleased old Tom more.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.