The first page of Jeremy Reed’s ‘autobiographical exploration of sexuality’ finds him with ‘a red gash of lipstick’ on his mouth, pondering whether to take the ten steps down to a beach where men sunbathe nude. He is androgynous, 16, ‘looking for a new species’. James Kirkup also admits to androgyny and to a passion for make-up, from childhood when he experimented with his mother’s make-up box, through the time when, as head of the English Department at the Bath Academy of Art, he appeared in his own play for children wearing white tights and with gold sequins on his upper eyelids, right into middle age. Swinburne had a sympathetic line or two for androgynes:

Love stands upon thy left hand and thy right,

Yet by no sunset and by no moonrise

Shall make thee man and ease a woman’s sighs,

Or make thee woman for a man’s delight.

Not that either Reed or Kirkup feels in need of Swinburnian sympathy, and my ‘admits’ a few lines back should really be ‘proclaims’. The writers have other similarities. Reed sees poetry as ‘an ineluctable vocation’, Kirkup says nothing matters but ‘my writing, my art, my poetry’. Both use quotations from Rimbaud as epigraphs, and are contemptuous of almost all recent English poetry. Reed calls it vapid, costive, and is especially hard on ‘the provincial librarian, Larkin’. Kirkup found no poets in the Fifties in whom he could take the slightest interest.

One might expect that their books would be about the poetry to which they are ineluctably dedicated, but in fact they are primarily concerned with disproving those lines of Swinburne’s by what seems at times almost ceaseless sexual activity. In Reed’s case, this is generally the giving and receiving of blow jobs, although he records an occasion when a French girl who had smiled at him once or twice took him into a barn, and after ‘her lips closed over my cock’ instructed him how to enter her. Kirkup is less candid about the details of his sexual activities, which seem mostly to have involved mutual masturbation. In youth this took place chiefly in the ‘cottages’ he haunted, where he often wrote poems while waiting for a ready partner. He records that as a child he used to visit urinals ‘hoping to catch glimpses of men’s cocks’, and later in Spain and Denmark he looks less at the faces of men who attract him than downwards to see the outlines of their ‘considerable equipment’. He mentions many ten-minute rather than one-night stands, along with detailed accounts of two serious love affairs. Reed’s lovers are called Bert, JB and X, but his writing is so deliberately fantastic that it is not easy to be sure whether they are real or invented. Since he believes that imagination is all, and what happens ‘is a questionable fact transmitted to a time-film’, perhaps it does not much matter.

Sexual activities apart, what do these autobiographical excursions tell us? Both writers are concerned to stress their fine sensibilities, Reed in a surrealist mode, Kirkup more in the manner of a Nineties aesthete. Reed claims that at the age of 19 he was already living in ‘a blaze of heightened perception’ prompted by drink and drugs. He believes poems are prompted by withheld orgasms, ‘the work on the page ... like the line of semen advancing’, and thinks the species is being transformed in a ‘psychophysical evolution towards androgyny’, a change in which his lipsticked self is playing a part. He seems to be striking a series of attitudes rather than expressing opinions permanently held, his most genuine belief perhaps being that when he performed poetry readings ‘stripped to a black leather or satin posing-pouch’, the poems took on another meaning. No doubt: but one connected to Jeremy Reed rather than his poems.

The last third of Kirkup’s book is given to the account of a love affair with a young American, ‘the most beautiful creature I had ever seen’, which is described movingly, although with some characteristic exaggeration. (‘I could be both Verlaine and Rimbaud. He was always Rimbaud.’) The two wrote poems together, and for a time Dana seemed to be not only a lover but that perfect friend whom Kirkup, like Frederick Rolfe, was always seeking. Kirkup’s book is liberally sprinkled with poems, most of them rather humdrum and low-spirited. The ones on which Dana collaborated are conspicuously more energetic and interesting. Kirkup’s final decision to cut free from the relationship because he was sinking his identity in Dana’s both as person and poet is told without affectation, and his refusal to do as friends advise and ‘put down roots’ through a permanent relationship reads as perfectly genuine. Typically, though, Kirkup can’t resist a final flourish. His lonely wandering life is, he says, ‘a gypsy trait from my Viking ancestry’.

Both these poets have it in for the ‘tight little poetic coteries’ they see as controlling the British scene, coteries from which they proudly claim exclusion. Yet Reed’s dust-wrapper mentions various awards and prizes, and Kirkup has had his share of prizes and appointments. Should they have accepted them, feeling as they do? What would Rimbaud have said?

Dannie Abse says firmly that his book is ‘autobiographical fiction’, not autobiography. ‘I have deleted my past ... and substituted it with artifice.’ It is hard to know what he means. Are the people mentioned in these pieces, father and mother. Uncle Eddie and others, invented? Is the vivid account of ending up in a hospital after an air-raid factual or imagined? No doubt reality supplemented by fiction is the answer, but there seems no need to make a to-do about it.

The young man from Cardiff’s collection is a bit of a rag-bag. Part One contains stories round and about schooldays, readable enough but not up to Dylan Thomas as a young dog. In Part Two ‘The Scream’ gives us Dannie (all right, the narrator), now a medical student, thumbing a lift to Cardiff from a lorry-driver. They stop at a sinister little café where he hears a woman’s piercing scream ‘like that in a Gestapo cell’. The lorry-driver has vanished. He now reappears, they resume their journey, the scream is unexplained. This is an effectively chilling story, and even better is ‘Madagas-car’, in which the narrator is a young locum who tries to help a recently married Australian woman, whose husband has holed up in a hotel and refuses to see her. The woman is a twin and her husband, seen by the locum, claims that the wrong twin has been foisted on him back in Australia. This may sound like a farce, but the story is full of enigmatic subtleties, the whole brilliantly handled. There are skilful though lesser stories in Part Three, and the whole book has a nostalgic feeling for Wales emphasised by a few poems, some of which, like ‘Last Visit to 198 Cathedral Road’, gain a good deal from their context.

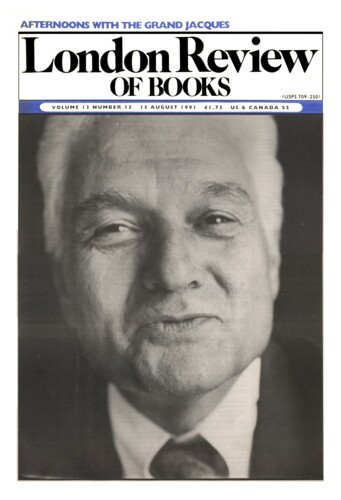

Michael Hamburger, born 1924 in Berlin Of German-Polish Jewish origin, but brought up in ignorance of Jewish traditions, is an example of the blessings and problems of mixing cultures. His father was a well-known paediatrician, and was awarded the Iron Cross in World War One. He realised life under Hitler would be intolerable, yet remained a patriotic German. The family came to England when Hamburger was nine: he went to school at Westminster and Lancing, then to Oxford, yet was never fully tuned to British habits, attitudes, ways of thought. String of Beginnings, published in 1973 and now reissued with a postscript dated 1990, is the autobiography of an outsider, and perhaps all the more interesting because he seems not to realise that.

Hamburger was determined from adolescence to be a poet. He knew Larkin and Sidney Keyes at Oxford, but found no English poets of his generation who matched his own severe cerebral and emotional intensity. He was a little too late to be influenced by the commonsensical poetry of the Thirties, which looked outwards at the world of events and objects rather than inwards at the depths of each individual soul. With the coming of war Thirties poetry lost out to the erratic romanticism of Tambimuttu’s Poetry London and the incoherent rhetoric of the New Apocalyptics. Hamburger drank in Soho with Tambimuttu and his cronies, admired Dylan Thomas’s ‘basic integrity’, and took him as a model for what he calls his derivative verse of the time. There were other models too, none of them good. The remark about Thomas, whose talent was wrecked precisely by a lack of basic integrity, and the praise Hamburger gives to some lines written by a friend that might be a parody of MacNeice’s Autumn Journal, suggests how far astray he was in youth, and perhaps is still, from understanding English poetry.

In the 1990 postscript he remarks on the ‘oddity’ of the fact that he is better-known as a translator than as a poet, but this is not odd at all. Even though he began to write in English and not German, it does not follow, as he suggests, that ‘the true home of a writer, qua writer, is the language he writes in.’ In writing poems (prose is another matter), Michael Hamburger does not use the language quite like a native, so that the effect always seems slightly derivative, an echo of some other poet one can’t quite place. Eliot, confronted with Hamburger’s early poems, and trying to say something pleasant about them within the limits of Eliotian caution, got no nearer than: ‘The actual writing is all right on the whole, though no word ever seems to be invested with a new life in the context.’ The verdict still seems good today, even though this honest, interesting autobiography is proof enough that for Michael Hamburger poetry really Was an ineluctable vocation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.