In the beginning there was Cookham, and Pa and Ma and ten other children apart from Stanley, including two who died in childhood. Cookham was Paradise, but Paradise ended with the 1914 War. Afterwards there were years of confusion, then the discovery of sex. And all the while there was religion, and paintings that tried to express religious feeling, latterly including always in various forms the artist and one or other of his two wives. That was the life of Stanley Spencer (1891-1959) who became Sir Stanley, and spoke often of his ‘belief in grandeur and great Art and Religion of the grandest kind ’. The belief was shown through paintings that, if not exactly the grandest, are possibly the biggest and certainly among the oddest done in Britain during the 20th century.

Stanley Spencer spent childhood and youth in ‘Fernlea’, one of a pair of semi-detached villas in Cookham High Street put up by his grandfather Julius. Pa was a music teacher, worshipper of Ruskin, read the Bible to the family. Ma took the children to the village Methodist chapel, something Stanley in the end found unsatisfying. ‘I have listened to a thousand sermons, and would like something to counterbalance this. I would like to read about St Francis and St Thomas Aquinas,’ he wrote in his early twenties. He showed an early talent for art, and was sent to the Slade through the benevolence of a local Lady Bountiful. He emerged from it in 1912, an almost dwarfish figure a couple of inches over five feet and weighing less than seven stone, already aspiring to the religious past and intent to identify it in terms of Cookham ’ s scenes and people. Spencer later believed that the pictures of this period represented a time of divine innocence in his life: ‘When I left the Slade and went back to Cookham I entered a kind of earthly Paradise ... I just opened a shutter in my side and out rushed my pictures.’ Then came the War, and after it ‘nothing was ever the same again.’

Religious themes are rarely absent from Spencer’s serious work, but it is certainly true that in these early paintings, regarded by many as his masterpieces, the beauties he discovered in the prettiness of Edwardian Cookham are blended with love of his family (his brothers, Pa, Ma and friends make frequent appearances) into an expression of lyrical feeling that vanished from his work after World War One. They avoid the eccentricities that show as early as The Last Supper (finished in 1920), in which the disciples seem to be examining their ludicrously long legs stretched out under the table, toes almost touching. Such distortions became more deliberate with time, and were often unpleasant, as in the apparently gigantic goitre of St Francis in St Francis and the Birds of 1935. Kenneth Pople, who writes throughout only just this side of idolatry, is never at a loss to explain such obscurities, very often referring them back to Cookham and its people. It is ‘not unreasonable to suppose’, he says, that St Francis represents Pa as he padded about in slippers and dressing-gown feeding hens and ducks. (Geese in the picture.) The dressing-gown itself is one Stanley’s brother Gilbert gave him when Stanley ‘went into hospital for his first gallstone operation’. And the goitre? This is ‘procreative symbolism’, which demands ‘that the saint be huge, female in form, indeed pregnant, his head ... equated in form to the function of the female breasts ... Stanley has placed the neck of the old man where a woman’s breasts would be.’ There is no arguing with such interpretations, some of which come from the artist himself. You find them acceptable, or as I do ridiculous, but either way this sort of explanation doesn’t really bear on the merits of the picture.

During the twenty years between the early paintings like the elegant, very deliberately stylised Swan Upping and St Francis lay the most bruising experiences of Spencer’s life. He went through World War One from 1915 onwards as a medical orderly, first of all in the Beaufort War Hospital, very recently converted from Bristol Lunatic Asylum, and later in Macedonia. The military side of the experience is re-created in the huge panels he painted for Burghclere Memorial Chapel, called by descriptive titles like ‘Ablutions’, ‘Kit Inspection’ and ‘Reveille’. Pople is sparing in his mention of possible influences on Spencer, but especially in ‘Kit Inspection’ the robotic nature of the figures is reminiscent of William Roberts, while the formal shaping of the mosquito nets in ‘Reveille’ might have been done by C.R.W. Nevinson. In relation to style, Spencer was apparently untouched by modern influences from Europe.

Apart from these panels recording military life which intermittently occupied several years, the work of what might be called Spencer’s second period was given to religious subjects, the Crucifixion, the Betrayal, the Robing of Christ, the Disrobing of Christ, and most notably the gigantic (18 feet long by 9 high) Resurrection in Cookham Churchyard in which the artist himself appears, along with his first wife Hilda and Sir Henry Slesser, later Solicitor-General in a Labour government.

Since a wife has been mentioned, it is time to deal with sex and Stanley Spencer, a subject dwelt on in loving detail in a TV documentary two or three years back. In 1925 he married Hilda Canine. Like her father and two of her brothers she was an artist, and her thinking about art and about life in general was, like Spencer’s, unsophisticated and idealistic. ‘The is-ness of you to me is like the is-ness of God,’ he told her. But Hilda was a Christian Scientist who did not approve of birth control devices. They had two children, but her husband felt inhibited from loving her ‘completely’ as he put it, even though she was ‘the most revealing person of essential joy that I know’. After several years of marriage he transferred his attentions to Patricia Preece. Patricia, like Hilda, was an artist, but this snobbish daughter of a colonel in the Welsh Fusiliers had a keen nose for cash and an eye on social advancement. She was basically a lesbian, living in Cookham with yet another artist, Dorothy Hepworth.

Her interest in Stanley Spencer was confined to his growing celebrity, and she was contemptuous of his work. She was eager for him to paint more landscapes, for which there was considerable demand, rather than the much less saleable religious or visionary paintings, saying after his death: ‘I never saw why he should not paint landscapes, as they were no worse in my opinion than his figure pictures.’ Their sexual relations were not easy, Spencer complaining that even when he got her to bed she ‘had a terribly difficult job to perform’. So did he give up Patricia? By no means. She was, he told Hilda, the ‘exact incarnation’ of the ‘Cookham Image which had always haunted me’. Hilda was the God Image, Patricia the Cookham Image, and he proposed setting up a ménage consisting of himself, Hilda and their children, Patricia and Dorothy. Such arrangements were and are not uncommon, but Hilda refused, divorced him, and in 1937 he married Patricia. He soon realised his mistake, and proposed to divorce her and remarry Hilda, but this never happened. When he was knighted shortly before his death Patricia was delighted to be addressed as Lady Spencer.

What should one make of the life and the talent? Hilda, writing to Spencer’s agent Dudley Tooth, said that ‘being with Stanley is like being with a holy person ... for he is the thing so many strive for and he has only to be.’ Never mind the effect, feel the sincerity, is what many admirers say. Certainly there is no doubt about Spencer’s passion for religion, which fused in his mind with sex, and he could not understand how people failed to see that his Resurrection of Soldiers was ‘a vast communion of saints’ and be moved by it accordingly. But he was both asking and attempting the impossible. This has been in Western Europe a secular century, and paintings of crucifixions, resurrections, last suppers, cannot possibly have the emotional meaning for us that they had five centuries ago. God, I read the other day, was very low in the ratings last Christmas, and in the same week Piers Paul Read was regretting that Madonna and not the Virgin Mary was a role model for the young, and Marina Warner saying that ‘the reality her myth describes is over.’

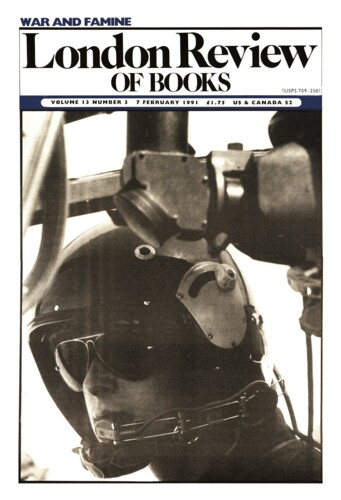

That, surely, is the basic reason why Stanley Spencer’s religious paintings are mostly ridiculous rather than moving. ‘What ho, Giotto!’ he cried when he had the commission to decorate Burghclere Chapel, but the fact that he found himself compelled to paint not frescoes but canvases giving the appearance of frescoes suggests the vast gap between intention and execution. Among the dozens of illustrations in this biography are two showing Giotto’s Last Judgment at Padua. The grandeur and serenity of the figures reflect an age of faith, the caricatural contortions of Resurrection of Soldiers only a desperate desire to believe. John Rothenstein, giving high praise to the early paintings including the splendid 1914 self-portrait that provides a cover for the biography, said much of the later work gave the impression of being stopped only by the margin of the canvas. Given another couple of feet or so Spencer would have filled it without premeditation.

The religious paintings brought to my mind those of the Victorian John Martin, whose Last Judgment, The Great Day of His Wrath and The Plains of Heaven were exhibited all over England with immense success, and even earned a reference in East Lynne to the ‘shadowy figures in white robes, myriads and myriads of them, for they reached all up in the air to the holy city’. In Martin’s gigantic pictures human beings are diminished by nature. The Deluge finds a mass of tiny figures herded together in the vain hope of escaping destruction; Belshazzar’s Feast concentrates similarly on the destruction of wretched little people, everywhere the works of God are seen to be terrifying in their power, men and women no more than tiny puppets. Benjamin Haydon called Martin a man of extraordinary imagination, but an infant in painting. Nobody would say that of Stanley Spencer, but in his approach to religious painting he was a kind of Martin in reverse. For Martin, in an age of belief, the triviality of man proved the Glory of God. In the 20th century Spencer’s desire to express ‘great Art and Religion of the grandest kind’ conveys in the end nothing more than the essence of Stanley Spencer.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.