Sunday night at the Hotel Bulgaria in central Sofia. Until the next electricity cut arrives, it is cabaret time. A succession of competent, Westernised acts unwind before a small, mute audience who have paid five levs each for the right not to applaud. On come four muscular, blond-rinsed girls, who go through a mixed routine, from rough-hewn disco-dancing to some Isadora Duncan stuff. They are well-drilled, energetic, and a long way from tickling the erotic; there is also something not quite right about them. Then, abruptly, one girl goes up on her left foot and slowly raises her, right leg out sideways. When it reaches nine o’clock, she hoists it with her hand and sweeps it up to the implausible vertical, cocking her foot horizontally across the top of her head. All is suddenly clear: the girls are ex-gymnasts, as they now confirm by ball-juggling, running round with streamers on sticks, and so on. The act ends, the small Bulgarian public exercises its right to be unimpressed, and a Western observer draws an inviting conclusion. Sport is no longer state-coddled in Eastern Europe, so here are four gymnasts, deprived of coaching and steroids, earning their corn as a Sunday night cabaret act – a living demonstration of the switch from communism to capitalism. What sort of progress is this? Hard to tell; but it looks a neat image for the strange and extreme transformation Bulgaria is currently undergoing.

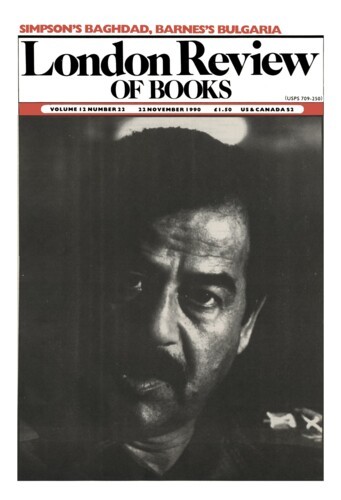

Bulgaria is the forgotten item in the East European unshackling, a country that is doggedly down-page: correspondents fly in for a few days only when things look like hotting up. ‘Why do you English dislike us?’ a member of the philosophy department at the University of Sofia asks me. We don’t, I say, it’s just that, well, it’s difficult to be interested in everywhere. Bulgaria is small, hangs off the very edge of Europe, and hasn’t really attracted our attention since Gladstone’s day. Other countries offered us the Berlin Wall, the Prague Spring, the Budapest Uprising, the Romanian Revolution. Here they don’t even talk of ‘the Revolution’, just of ‘the Changes’, or ‘What Has Happened Since November’ (10 November 1989, when President Todor Zhivkov was manoeuvred into resigning). Forty-five years ago Bulgaria was turned into a Communist state when the Red Army marched through; now it is stopping being a Communist state. It is not, however, being exactly newsy about the process. For months before I came here I clipped every reference to Bulgaria in the papers. A typical item from the Guardian of 24 April 1990: ‘Bulgarians Find Mass Grave.’ The story appeared tellingly under the headline ‘News in Brief’, and ‘mass grave’ turned out to mean the burial place of 11 people. Not quite ‘mass’ enough for our taste? In August the country finally provided work for newspaper picture desks when demonstrators burnt the former Communist Party headquarters. ‘This is our storming of the Bastille,’ said one opposition leader. But walk past the building today and the damage hardly shocks: some blackening round a number of windows, a couple of which are boarded up, but no burnt-out shell. Two or three windows along from the scorch marks, early-evening lights are on and someone is at work. I try to explain to my questioner: if only things had been nastier, we might have been paying more attention.

Bulgaria. ‘Did you know,’ someone told me before leaving, ‘that the reserves of the Bulgarian central bank are held in rosewater?’ (This turned out not to be true.) Bulgaria. Good cheap wine. Only not as much as before, because during Gorbachev’s anti-alcohol campaign Bulgaria showed its loyalty by ploughing up some of its finest vineyards. Bulgaria. Yoghurt, the best in the world. Only now it is some of the scarcest in the world. There are shortages of many things in Bulgaria, and these shortages have a cruel logic. There is a shortage of yoghurt because there is a shortage of milk because there is a shortage of animal feed so the cows are being slaughtered (which means, on the other hand, that there is a temporary supply of beef). Similarly, there is a shortage of eggs because there is a shortage of chicken feed so the hens are being slaughtered (which means, on the other hand, a temporary supply of laying birds turning up as roast chicken).

Currently rationed are eggs, sugar, flour, cheese, ‘yellow cheese’ (a key distinction between cheddar and feta styles), washing-powder, cooking oil and petrol. There are also three more ‘numbers’ on the ration coupons, representing unknown items whose rationing has yet to be announced. Some items aren’t rationed for the simple reason that they’re unavailable: sausages aren’t on coupons, but then they can’t be found anyway. There hasn’t been alcohol in the shops for over a month. The black market flourishes; you will find a bottle of spirits in Gypsyland. Old people say that the situation is now worse than it was just after the war.

There are one-hour electricity cuts every three to four hours, rotated by district. Petrol is largely unobtainable: a friend’s husband waits nine hours through the night at his local garage; the record length of queue so far has been three and a half kilometres. Motorists wait not in the knowledge that a tanker is coming to a particular station, but in the hope that one might.

Bulgaria has lost heavily in the Gulf crisis – $1.4 bn being the latest estimate – and the oil it was due to receive from Baghdad in exchange for arms has not turned up. ‘We sold weapons to Iraq,’ explains a student with some embarrassment. (‘So did we! So did everybody!’) Even those cars converted to run on gas are not exempt: gas for cooking but not for cars, the announcement comes, and a spontaneous protest blocks one of the main roads into Sofia. All this makes for an eerily altered city: the trams still trundle, and the articulated buses hose the air with 100 per cent pure pollutants, but Sofia is a city temporarily returned to the pedestrian. At night, with minimal traffic, few street-lights, and the population hurrying uncertainly across wonky pavements, the outsider gets a safe, almost historic thrill: that of visiting a wartime city without the bombs.

I am here for nine days for a simple reason: my novel Flaubert’s Parrot is being published in Bulgarian, and I couldn’t resist. Why should they be interested? Why should they be interested now? It seems strange and gratifying that they are. My publishers, Narodna Kultura, have printed 5000 copies, which sounds optimistic, being almost double the first printing in Britain.

My opening engagement is a signing at a bookshop in the Palace of Culture. When we arrive the place is full, I assume because it is somewhere out of the cold. Ninety minutes later we have sold 300 copies, which makes me slightly embarrassed. Sofia is a city where people walk around with a plastic bag in one hand in case they see something to buy, and where a queue attracts attention because its existence implies that there might be something worth buying at the head of it. Perhaps people have joined my queue imagining that they will be rewarded with washing-powder. Then they get to the front and discover a foreigner with a poised biro; they buy the book out of politeness. I feel better about this when I ask how the price of my novel – 1.8 levs – compares with that of other goods. ‘Oh, that’s about two cups of coffee or half a kilo of yellow cheese.’ Which seems about right.

The book-buyers are much more disparate than in Britain: taciturn becapped old workers line up alongside bright young students. A middle-aged lady looks me directly in the eye and says: ‘We are a poor country but we love books.’ It is a straightforward statement, and not in the least mawkish. It is also true. At a meeting with editors from two of Bulgaria’s literary journals, I am unable to tell them anything new about British writing. ‘who is à la mode? they ask, but the names I suggest are all highly familiar; finally, I score with a couple of first novelists and an arcane short-story writer.

On the other hand, there is a lot for them to learn about how publishing operates in the market economy towards which they are being frogmarched. In the past, publishers haven’t had to make more than a marginal profit (and had no incentive to make a larger one as the surplus was taken by the state); they were privileged in their access to paper; they didn’t spend much time worrying over reprints (the edition was the edition, and that was that), and had the luxury of a few non-market ideas about writers themselves. One magazine editor told me she would like to print my next book. ‘You mean, an extract?’ ‘No, the whole thing.’ ‘But ... surely that would mean the sales of the book would be damaged.’ ‘No, it would be good publicity for you.’ ‘Hmm. And just out of interest, how much would you pay? ‘Oh, we do not pay.’ ‘Nothing?’ ‘No, it would be good publicity for you.’ But the world of paper shortages, realistic book-pricing and normally greedy authors is coming, inevitably. Svremennik, the magazine of contemporary literature, has financed itself for the next year by bringing out Forever Amber in a monster print run. On the other hand, an editor at Panorama, the leading magazine for literature in translation, fears they might have to close

Meanwhile, other, newer publications abound. Dozens of newspapers have sprung up, and are thrust at you in restaurants and public gardens. Censorship, both political and moral, has vanished. Animal Farm has been published, and my editor shows me the first Bulgarian copy of Darkness at Noon, fresh in from the printers. Barely two years ago, she was obliged to remove from a translation of the Flaubert-Sand Letters Flaubert’s critical remarks about the Commune. ‘Also, we have discovered eroticism. We are going to translate Henry Miller.’ (How good an idea is this?)

Outside, in the streets, trainee pornographers crouch over upturned beer-crates selling the first Bulgarian girlie mags – while plastic-wrapped stacks of the Kama Sutra (local version, 64 pages approx.) are heaped up near the tourist shop. Besides erotica, there is an upsurge of interest in astrology, numerology and other esoteric cults – never has the question ‘What is your star sign?’ featured so often in author interviews. This seems to indicate more than just curiosity about the previously forbidden. When one closed system of thought fails, the intellectually giddying prospect of relativity makes other explain-it-all cults attractive. Even the Moonies have arrived with their own version of the Total Answer. The other week, twenty or so young Bulgarians from the town of Vratsa left for Moonie training in Paris.

Not that this departure would have stood out: during the past nine months 150,000 Bulgarians have left the country. Crossing the square in central Sofia, I notice a cluster of young men, an intense, whispering vortex some ten deep. What are they swirling around – some new item of erotica, a game of Find the Lady? No, they are establishing the order of precedence in the visa queue for the American Embassy across the street: you are allotted a number, and come back each day to find out how far up the list you have risen. America is hard to get into, but easier than Britain, which is not worth applying to; Canada is welcoming; Israel operates its Law of Return. Most of the 150,000 are young men, setting off with what little hard currency they have scraped together for whatever country will have them, and hoping to send for their families later (which might double the figure to, say, 300,000 out of a population of only nine million). Some emigrants head for Harare in an attempt to get into South Africa. They say that South Africa is accepting workers, white, skilled or unskilled, but preferably without awkward intellectual qualifications. From Bulgaria to South Africa? So it’s that bad?

My translator’s brother is an apiarist in Plovdiv. He may not be an apiarist much longer, though, because this year all his bees have been born without wings. Without wings? ‘It is a mutation.’ What causes it? ‘We do not know.’ Other apiarists have found the same. Chernobyl? ‘We do not know.’ In Bulgaria the opposition first solidified around the Greens, which from the outside seemed curious, explicable perhaps as a canny move by the ruling party (let them protest about the trees and they won’t notice more important things). From the inside it appears much more logical and inevitable. The initial protests centred on Ruse, a town on the Danube whose inhabitants were being systematically poisoned by a Romanian chemical plant across the river: children coughed from birth, women wrapped scarves round their faces before they went shopping. Why wasn’t anything done about it? ‘Because Zhivkov and Ceausescu were always kissing one another.’ Even now, a year after the two countries deposed their kissing masters, the pollution continues; Bulgaria has taken the matter to the United Nations.

The Danube is a drain, the Black Sea a chemical toilet. Bulgaria’s nuclear energy plant has been declared more dangerous than Chernobyl, but continues to run (and supply 40 per cent of the nation’s energy). In this country, no lake you pass seems complete without a squat shoreside silo committed to poisoning the fish. What look like gimcrack aqueducts teetering across the landscape are not bringers of water to the towns, but of filth to the waters. The severity of pollution is slowly beginning to come out. Kurdjali, for instance, is a town in Southern Bulgaria which claims 360 days of official sunshine per year and is the theoretical location of a rare form of wild peony. It is also the actual location of the country’s biggest lead and zinc plant. The results of soil tests made around the town six years ago have recently been declassified: lead concentration exceeded the permitted level by 42 times, zinc by 30 times, cadmium by four times. Of the eight thousand local children recently examined by doctors, 34 per cent were found to have pathological disorders.

If nations were children, this place would be taken into care; the world would be seeking a foster mother for it. Bulgaria was a chubby little country boy on whose flesh Communism and heavy industry decided to stub out their cigarettes; the burns are everywhere. (You can follow the gradation of priorities in Zhivkov’s Bulgaria from the currency: the one-lev note features an old stone tower; the two-lev, a girl picking grapes; the five-lev, a Black Sea resort; the ten-lev, a communal farm; the 20-lev, a showplace of heavy industry.) To make matters worse, Bulgaria was a country ill-suited to its macho conversion to heavy industry: it lacked raw materials of its own; its processing and refining plants were built to fit Soviet needs. There is an oil refinery on the Black Sea which is capable of refining only Soviet oil; now the Soviets have distanced themselves and demand hard currency from Bulgaria. This country was so much a client state of the Soviet Union that Zhivkov twice tried to sell it to the USSR – ‘internationalism in action’, as he put it to Brezhnev. But not even Brezhnev fancied the offer; and then Gorbachev pulled the plug.

There is as much agricultural land in Bulgaria as there is in Britain; now that it has been thoroughly polluted, the Government is trying to return it to the people. A re-privatisation bill is before Parliament, but the practical difficulties appear insuperable. How do you give back land you took forty-five years ago? For a start, you might have killed the owners while taking it (no figure is available for those who disappeared at the time of the Communist takeover: one estimate I hear is thirty thousand). Or if you didn’t kill them, they might have died, or moved away, or left the country. And even if they or their heirs are still around, why should they want this chemical tip back? To start a farm from scratch you need a bank loan and farm machinery. You can get a bank loan, but it comes in soft currency, and you need hard currency for farm machinery, which isn’t made in Bulgaria. So why should prospective farmers take on the Government’s problem? This is the political situation writ small. Writ large, it goes like this ... The Zhivkov-free Communist Party (renamed the Bulgarian Socialist Party) was re-elected in June, and has been trying hard in recent months to get the opposition parties to join in a government of revival, unification, forgiveness or whatever. But the opposition parties decline this septic embrace: you screwed it up, they say, so now you unscrew it.

Much of this would be intolerable without a sense of irony, which is locally well-nourished. The conservative Communists, for instance, are colloquially referred to as Heavy Metal. (While the English have Irish jokes, and the Americans Polish jokes, the Bulgarians have ... Armenian jokes.) As for Bulgarian heavy industry, did you hear the one about the international aeronautical conference? No? Well, there is this conference held to solve the problem of an aeroplane one of whose wings keeps falling off. Various experts take the podium and outline their complicated proposals. Finally, Engineer Ganev of Bulgaria gets up and says the matter can be easily solved: all you have to do is make a perforated join along the line where the wing meets the fuselage. How on earth would that help? ‘Because in my experience nothing ever tears along the perforations.’

Bulgarian Airlines announces that it is cancelling some flights because of the oil shortage. There is also, for that matter, a shortage of lavatory paper. And here is another knock-on effect. We pass a cemetery, and I ask my guide whether people in Bulgaria prefer to be buried or cremated. She smiles. ‘There is a crematorium in Sofia, but it isn’t working. No petrol.’

The Bulgarians I meet are direct, friendly, intelligent, necessarily ironic and prodigally generous with what little they have. (Let’s not be sentimental: the surly bastards are as surly as elsewhere, and there is a special breed of grim crones who guard the lavatories and whose speed at transferring a 20-stotinki coin from saucer to pocket rivals that of a lizard’s tongue.) They are noticeably anxious, about the present and the long term future: for instance, many couples are restricting themselves to one child. ‘A friend of mine has just had an abortion,’ a woman tells me. ‘Previously I would have argued against it, but given the social conditions I didn’t think I could.’

There is also much pride and lack of self-pity. ‘We haven’t suffered enough,’ one says. ‘We’ve been too close to the USSR. Now we have to learn the hard way.’ This, unfortunately, isn’t going to be a problem. To the north, the Soviet Union displays froideur and has enough troubles of its own. To the east, Turkey remembers Zhivkov’s persecution of the indigenous Turks in Bulgaria and the mass exodus it caused (not only were living Turks compelled to Bulgarianise their names – even the names on tombstones were chipped out and recarved). And to the west lies ... us, and here Bulgaria has always held the short straw. Other East European countries have natural or historic links with particular West European countries; some also have a strong lobby in the United States. Bulgaria has none of these. ‘Who is going to help you?’ I ask. ‘We must show that we deserve help. We must show that we can work.’

Who will help them? Robert Maxwell says he is helping them, which is a dismaying thought. To be introduced to the delights of capitalism by Robert Maxwell? By Robert Maxwell, friend and publisher of Todor Zhivkov? Not surprisingly, Bulgarians are wary of the Great Benefactor, though his name is much in evidence – if only for a shortage of other benefactors. One place you will spot the name is on the shirts of the Slavia football team. This is one of the oldest clubs in Bulgaria, founded in 1913, and briefly renamed Shockworker in the Fifties. A Plovdiv novelist, reporting on the current popularity of striptease (when asked to explain their surprising proficiency in the art, the strippers replied that they had been practising before the party bosses for years), mentions that some football clubs, in an attempt to boost attendance, have been staging acts before the kick-off. In this weather? Imagine a goose-pimpled girl in the centre circle as warm-up for a visiting team wearing MAXWELL across its chests: a bizarre, but not implausible image of Bulgaria today.

‘Are you writing down all the absurdities about our life in your notebook?’ asks my translator. Well, only up to a point; and the Bulgarians themselves are quick to help you spot them.

An absurdity of the past. In Plovdiv, below the heroic monument expressing gratitude to the Red Army (‘Only Russian tourists come here’), five corporation gardeners are busy demonstrating the Communist theory of ‘full employment’: four women and an old man with an antique watering-can, between them planting out a small box of pansies, and each straining to operate at only one-fifth capacity. An absurdity of the transition. During the election there was an attempt by the Communists to bribe the Gypsies, some of whom received their voting slips in an envelope also containing a little money; the scandal came to light when a number of voters, imagining that the money had to be passed on to the electoral officials, dutifully sealed the bribe up in the envelope. An absurdity of the future. How do you retrain a supposedly redundant secret police force? Earlier this year there was an announcement in the newspapers that the first two Bulgarian private detective agencies had been founded; the subtext was clear, and provoked more laughter than reassurance.

But ‘absurdities’ shade easily into the crueller mockeries of infant capitalism. There is inflation (the price of potatoes has risen sevenfold), a roaring black market, and the prospect of large-scale unemployment. If what used to be East Germany is being told that it’s in for a hard time, that it must learn to shape up, that 30 per cent unemployment is coming and showpiece factories must be closed down, what must friendless Bulgaria expect for it self? ‘Vulnerability’ is a word you hear a lot; you also hear ‘period of transition’, ‘shame’ and even ‘national demoralisation’. ‘But look what you have gained since the changes,’ I argue. ‘Your borders are open, you can say and write what you think.’ Yes, they reply, so now our young people are free to leave, and we are free to say more openly that conditions are now the worst in living memory.

Perhaps freedoms suddenly gained are just as suddenly taken for granted; perhaps the released lifer always misses the certainty of stone walls. But there is another phrase you hear, one initially surprising to Western ears. This is ‘the death of idealism’. In the West there is currently much moral and economic triumphalism, and it suits us to think of the East as a place where evil despots held down a cowed populace whose main ambition was for better consumer goods. ‘We did not always think that money was so important,’ a professor tells me (and he should know, since academics were often paid less than workers). Even if you saw that the country did not work, that the Party was systematically betraying the principles it preached, you could still be idealistic about how things should be, how they might be. Now these possibilities seem to have gone. There are no second chances, no time to find a middle way. East Germany has discovered this, as all its laws are brought into line with those of the West. What chance for Bulgaria as it moves anxiously into the chill embrace of the Market? ‘The death of idealism’. Gymnasts turn cabaret dancers, and the secret policeman turns gumshoe. Moonies scoop up the young, and a stripper prepares the crowd for the Maxwell football team. In the churches here, you can light candles at two levels: those at the regular height are lit for the living; those at floor level are lit for the dead. In Sofia Cathedral these flickering appeals for intercession are everywhere. At a rough count, candles for the living exceed candles for the dead at a rate of 20 to one. This isn’t surprising. It is going to be a harsh winter in Sofia.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.