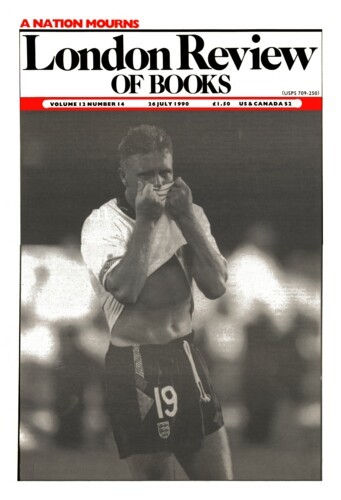

‘Of all nations’, writes Ian Ousby, ‘we’, the English, have ‘perhaps the most strongly defined sense of national identity – so developed and so stylised, in fact, that we are frequently conscious of it as a burden or restraint’. I wonder what he can possibly mean by that. The most anomalous thing about England in comparison with all other European nations (of course it isn’t a nation, but even in comparison with Scotland and Wales) is that it doesn’t have the formal marks of national identity acquired even by Iceland or Finland, Luxembourg or Albania. It has no national anthem – ‘God save the Queen’ is played at football matches, but that is shared with other parts of the UK, who, however, don’t play it (except for the Northern Irish, who are making a political point). It has no national dress, nor any evident national icons in the tartan/leeks/thistles class. St George’s Day attracts no celebrations. It does have a national flag, but not everyone knows what it is. A football commentator remarked that he was pleased to see ‘nearly as many’ St George’s Crosses being waved as Union Jacks, when England played Cameroon in the World Cup. No Union Jacks were on display at Scotland’s games. At a recent conference in Denmark I asked some forty Danish Anglicists if they knew what the English flag looked like. Yes, they replied, it’s that red, white and blue one with crosses going different ways. At least they were pleased to discover that the English flag is the exact reverse of the Danish one, for, as Saxo Grammaticus wrote long since, history in the North began with two brothers, whose names were Dan and Angul. But that particular national myth is unknown in England.

The point could be drawn out by considering the strange behaviour at rugby internationals (the introduction of ‘Land of Hope and Glory’? All the Protestant Ulstermen standing to attention for ‘The Soldier’s Song’?); or the nature of money (English notes and coins, Scottish ditto, but just try passing British Linen notes south of the Tees, Welsh coins only, Northern Irish neither but till fairly recently an identical, different, non-legal-tender Southern Irish currency). But there is enough already to qualify Ousby’s assertion: if England has a strong national identity, it does not depend on the kind of props thought normal by everyone else, nor, one might add, on any halfway informed sense of history, or of racial – still less linguistic! – origin. Churchill started his History of the English-Speaking Peoples with Julius Caesar’s invasion of Kent, a fixture which cannot have been attended on either side by anyone who spoke a word even of Utter Ancestral English, since even the Romans at that time had not started recruiting their Gurkha-equivalents from the far fens of Slesvik. Did Churchill mean History of Britain (and I’d better include the Americans and Anzacs?) Did he, in true English style, not give a damn? Perhaps the question is: should we? Maybe it is a sign of maturity and inner self-confidence to be the first nation in Europe not to need a national anthem/flag/dress/history/myth of origins. We meant the Act of Union, even if the Scotch did not (and before anyone writes in to complain about ‘Scotch/Scots’ etc, read the entry under ‘Scotch’ in the OED – it is a form at least as correct philologically as ‘sassenach’, but, revealingly, people are extravagantly punctilious about the one and regard the other with mild indifference).

Still, if the English are indifferent to national feeling in all but games – where, however, they insist on retaining it and FIFA be damned – what is this about ‘Englishness’? It is this question that John Lucas sets himself to answer, in considering the poetry of two centuries. He has one immediate cultural handicap: he cannot refrain from sniping at his own side (the English), as if to provide credentials of fairness. But what he says often seems more compulsive than fair. When he gets to Browning’s ‘No Briton’s to be balked’, he labels this the product of ‘chauvinistic Englishmen’ and goes on to say (back to football) that ‘when the English want to parade the virtues of English teams and/or their fans they insist on the “English”. When things go wrong, it is the “British” who are to blame.’ As regards Browning, this is the exact obverse of what is said. As regards football, I can’t imagine where Lucas has been living. The English/British distinction has been drawn much too firmly by FIFA in recent years for it to have escaped anyone who follows football. And what does he mean by calling Culloden a ‘massacre’, the ‘brutality of the English against the Scots’? Whatever happened afterwards, Culloden was a battle, no more one-sided than many: both armies had firearms and cannon, and if the Hanoverians used theirs more professionally on the day, that – as Bobby Robson would say – was what the whole thing was fought to prove. Cumberland’s 15 battalions also included the Royal Scots, the Royal Scots Fusiliers and Sempill’s Borderers, not to mention the eight companies of Campbell Highlanders. It was a British army. But, in exact reversal of what he himself says, in Lucas’s account, when things go wrong it is the ‘English’ who are to blame.

This naturally affects his definition of ‘Englishness’. It becomes a quality defined by negatives. It must not be something shared with the other ex-nations of Britain. It must also have nothing to do with the national government based in London, with apologists for it or a literary consensus based on it. True Englishmen either become non-nationalists and ‘citizens of the world’ (Swift, Goldsmith), or in some way or other spokesmen for a deep commonalty (or maybe a depressed commonalty) surviving below the Hanoverian consensus (Blake, Stephen Duck, the poet-labourer, who drowned himself in a fit of despondency). In a way, Lucas is most interesting about the poets in between these groups, the traitors or defeatists like Wordsworth or Tennyson. Both men, after all, had strong dialect interests which might qualify them as spokesmen for the common people, the native English. But their politics disqualify them. Lucas accordingly spends time and trouble picking out, as it were, the sociology of poems like ‘Old Man Travelling’. Why does the old man address the poet as ‘Sir’? Because the poet is a gentleman, and gentlemen, Wordsworth included, were ‘on the side of England’s war effort against Napoleon’. But because of that war effort ‘large numbers of non-gentlemen had to be press-ganged’: and that is why (says Lucas – there is no indication of pressed man as against volunteer in the poem) the old man is going to take his last leave of his son, the mariner

Who from a sea-fight has been brought to Falmouth

And there is dying in an hospital.

The burden of the poem then is an unstated rebuke. ‘Thanks to your kind, sir, my son is dying.’

What happened to ‘England expects ...’? Nelson, of course (according to legend anyway), in true English style didn’t say, ‘England expects ...’, he said, ‘Nelson confides ...’, but the signal midshipman told him neither word was in the code-book, so he had to change them. Still, Lucas is insisting on two nations, and a true England, just where national pride, at whatever cost, was most intimately involved in one. One can say this militarism is all false and wicked, like Tennyson on the Light Brigade and on the Irish-born but defiantly English Iron Duke – ‘You might as well call a man a horse because he was born in a stable’ – but it’s hard to say that it’s un-English. On occasion, too, it seems to me that Lucas goes easy on revealing failure just because he likes nationalistic stereotyping too little to engage with it. What a strange character is Tennyson’s Arthur in Idylls of the King, for instance: the only Arthur since the 12th century not to be the incestuous father of Mordred, and at the same time the most rigorously de-Celticised and Anglicised figure since Layamon’s. What a fate for the hammer of the Saxons, the great obverse of Edward I!

All these arguments create in the end a strange, mixed, twiddle-the-tuning-knob kind of effect. I feel sure Lucas is wrong in general, and wrong just because of that culturally-biased, bend-over-backwards, self-exculpating mode so characteristic of the English upper and middle classes (always so keen to point out that they have Irish/Welsh/Scottish/American/Tasmanian grannies, and so aren’t really English at all, but something much more wild and interesting). Against that, the details of his inquiry into poem after poem are strikingly suggestive, even if you draw from them conclusions exactly opposite to the ones suggested. English history in the 18th century (and at a popular level usually now) has been much more thoroughly colonised than any in Europe. That is why, one feels like saying, Gray had to go in for this stuff about Welsh bards from Snowdon, Norse heroes from Clontarf, and Gododdin translations from Edinburgh; the Old English epic remained unknown to him because no Englishman could read Old English from the later Norman period on, till the language was rescued by Dutchmen, Icelanders, Danes and Germans. Walter Scott’s normally strong sympathy with early epic stopped at Saxon romance with the remark that ‘Mr Turner has given us the abridgment of one entitled Caedmon, in which the hero ... encounters, defeats, and finally slays an evil being called Grendel’. It’s barely credible! He’d never have got away with it if he’d been writing about some Owen or Urien. But Lucas’s English lack of interest in historical English prevents him from saying this, though he does have interesting remarks about marginalisations and the un-Hanoverianness of the epic virtues. Similarly, one might assert, if there is one civilised thing about England now, it is the very general acceptance of free access to land via footpaths and National Parks, an acceptance thrashed out over centuries of bickering about private rights v. common rights. That bickering, as Lucas points out, has produced a flourishing literature of poems about arguments about wood – ‘Goody Blake and Harry Gill’, but see also Harley MS 2253, ‘the wodeward waiteth us wo that loketh under rys’ – as of poems about enclosures and deserted villages and customary rights, or poems about felled poplars (Cowper), fallen elms (Clare) and goldengrove unleaving (Hopkins). Lucas has drawn out the threads of these continuities admirably. But he will see them as defeat for true England! ‘The cottage loom was silenced ... The estate was sold ... great changes have been wrought/In all the neighbourhood’: the end of ‘Michael’, we are told, expresses an English experience ‘in danger of being not merely exploited but exterminated’. Massacres again! And it didn’t happen. The English genius – or so we used to be told – is for compromise: and over issues like dialects or footpaths or national anthems a tradition of confused compromise has been more successful, even in literary terms, than Lucas allows.

As is proved very clearly in Ian Ousby’s book on The Englishman’s England, a study on the rise of internal tourism. It is full of comic moments: Stratford Council in 1622 paying the actors six shillings ‘for not playing in the Hall’, i.e. for going away as soon as possible; the vicar of Holy Trinity, Stratford, not long after the actors were paid to stay away, making a conscientious note in his diary for the visitors, ‘Remember to peruse Shakespeer’s plays and bee versed in them, yt I may not bee ignorant in yt matter’; the old woman quoted by Wordsworth in her reaction to tourism and the picturesque – ‘Bless me! folk are always talking about prospects: when I was young there was never sic a thing neamed!’ Yet there is a strong tension in the tale as well. Tourist sites like Poole’s Hole or Tintern Abbey very soon created a class of beggar-guides whom visitors found sickening, disturbing, and eventually heart-hardening as they told each other protectively that there ‘was not one true object of commiseration among the whole’. Wordsworth’s Prelude meanwhile praised the beauty of Mary Robinson, the ‘Maid of Buttermere’, and that and the panegyric of her in Budworth’s Fortnight’s Ramble to the Lakes (1792) made her famous as an object of connoisseurship. But fame attracts notch-cutters, scalp-hunters. Poor Mary was deceived by a con-man later executed at Carlisle, and then of course, as a ‘type of innocence seduced’, became even more of a tourist attraction than before.

So she married a farmer and by 1819 figured in the Tourist’s New Guide only as a ‘bulky wife ... blessed with much good humour’. Good for her. And in the same way other institutions slowly hacked out compromises between old easy habits and a new age of freer travel. The assumption that gentlemen’s seats were always open to visitors (see Pride and Prejudice) buckled under a wave of vandalism, but made Mrs Hume, the housekeeper at Warwick, £30,000 in tips. By 1784 some gentlemen had got as far as tickets, opening hours and printed regulations, all consented to in a hit-or-miss fashion. It will all end in disaster, Ousby warns. Sooner or later the ‘epitaph of all tourism’ will be ‘Done because we are too menny’. But in the meanwhile tourism in England has been a singular pleasure for ten generations of English people, not all upper-class, and has contributed to that strong and wide, if shallow and spectating, love of countryside one can see still everywhere from Emmerdale Farm to Last of the Summer Wine.

What Gerald Hammond’s book on Fleeting Things adds to this perspective is the strong sense that no matter how far back you go, there is always a Golden Age just out of reach in the past, to contrast with the unfortunate, tourist-ridden, prospect-haunted, class-conscious, deeply-divided present. In 1817 Wordsworth wrote that ‘farmers used formerly to be attached to their landlords, and labourers to their farmers who employed them. All that kind of feeling has vanished.’ But when was ‘formerly’? Nearly five centuries earlier the author of Wynnere and Wastoure was lamenting much the same kind of decay. In between, Hammond has no trouble finding poets attempting ‘to restore the practices of a once vigorous peasantry’, and lamenting interim: ‘ ’Tis not, what once it was, the world.’ Hammond, however, is much more interested than Lucas or Ousby in holding a balance: he has poems against enclosures and ballads in favour of them; like Lucas, he sees poets complaining about how ‘common wisdom’ has dwindled to individual antiquarianism, but at the same time indicates a mass of popular and learned proverbial poetry; he exposes Cavalier verse almost as grovelling as Tennyson’s in its account of the blessings poured by King Charles on ‘this obdurate land’, but also points out the anxiety and tension in Davenant’s ‘To the Queen’ of 1641, with its cautious/daring couplet:

In Kings (perhaps) extreme obdurateness is as in Jewels hardness in excess.

I don’t suppose politics was any more real in the 17th century than in the 18th, but Hammond makes it seem a matter over which an honest man could take two views, or none, which is not the case (in intention at least) with Lucas’s account. It is hard to resist the notion that this engaging openness has something to do with Hammond’s early and determined statement that what he is interested in is things, events, physical objects, not emblems or abstractions: so that there are whole chapters based on Charles’s flagship, The Sovereign of the Seas, on games, famous trials, the churching ceremony or blushing. Hammond’s views on sex strike me with a certain alarm – is ‘the blush of a bashful virgin’ one of the ‘most civilised’ sights one can see? – but I suppose some go for blushes, some for footpaths.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.