An article in the Independent of 10 July was headed with these remarkable words: ‘Patrick Barclay reflects on a World Cup which was largely lacking in drama, individual dynamism and moments to cherish in the memory.’ This is not a description of the World Cup that I have been watching. But it is a good description of the coverage of the football which was offered by Patrick Barclay, by other British journalists, and by experts and commentators who were heard from on television. The 1990 World Cup produced, as it was bound to, its disappointments, patches of dullness and travesties of justice. It was doubtfully regulated and often poorly refereed. But its best stuff was enthralling, and as an occasion in the history of the human race its interest was first-rate. No one team was a match for the Brazilians of 1970 and before, but the Italians were among the most skilful and beautiful sides ever to grace the world game: the true winners of the cup, in my opinion, let down at the last by a lack of aggression and brute force, and of the luck that was so lavishly bestowed elsewhere.

The press and television coverage, pictures apart, measured up to very little of this. At worst, it was meanly patriotic, in a rather twisted sort of way, and even, yes, racist. England was both entitled and unlikely to do well, it could be felt at the outset, and it was a shame and a disgrace when at first they didn’t. When matters improved, the tabloids turned their coats and erupted with praise. ‘How could our lads play like that?’ asked the Sun at the beginning. ‘They couldn’t play, sneered the critics,’ said the Sun at the end. ‘How wrong the world was.’ Soccer journalists are different from other critics in that they tend, literally, to know the score, and they are less forthcoming when they don’t. Here, in the quality papers I saw, most of the correspondents were unforthcoming both before and after the result. It was a relief to read Hugh McIlvanney in the Observer on the Sunday.

Just over a year ago a previous diary of mine had this to say about the young English player Paul Gascoigne, allegedly wayward but already deeply acceptable to the crowd: ‘Bobby Robson’s team had hardly left the field, after the recent defeat of Albania at Wembley, when he was disparaging the contribution of Paul Gascoigne, who had come on late in the game to score one goal and make another – admittedly, against a beaten side: Gascoigne had been disobedient and had wandered about. Robson seems to like the player, who started out, as he did himself, in the North-East: but there was a wish to put him down ...’ The England manager Bobby Robson was on record as suggesting that Gascoigne was ‘daft as a brush’. Those were the days when we were to think that Robson in his maturity was worried about Gascoigne’s maturity. The message entered the media in the form of sermons from journalists sympathetic to the manager, as many were not – many were his unscrupulous enemies. For David Lacey of the Guardian Gascoigne had a tendency to give away the ball and to be a clown. It was not surprising that his place in the national team remained less than assured. On the eve of the tournament Kenny Dalglish, the Liverpool manager, declared on television that if it was up to him he would not play Gascoigne. Which enables one to say, what with one thing and another, that this World Cup has flashed a light on the psychology of management.

Managers are apt to favour players whom they can control and are sometimes jealous of those with an authority of their own and of those whose claims are pressed. The manager of Italy had not been keen to play Schillaci, soon to be their hero, and the Cameroon manager had wanted, together with the team, to exclude Roger Milla, a subtle player and roasting finisher, now in his thirties, who helped his team to make the first African challenge in the history of the tournament. It was rumoured that the local despot had insisted that the elderly fellow play. Nice one, despot.

England started out in disarray. The news was of big toes needing to be attended to. Bryan Robson had to take his toe home, despite the attentions of a faith healer, flown in from darkest England with the assent of Bobby Robson, who seemed to set himself to give the impression that Bryan was indispensable to the team and that he would have to be dispensed with. ‘My heart bleeds for the skipper,’ he said. It was as if this individual player mattered more than the team – which was not how he had appeared to feel in the context of Gascoigne’s jokes. For the manager the team consisted of ‘the lads’, whom England expected to do as they were told. I doubt whether there were any lads in the (no less disciplined) Italian team.

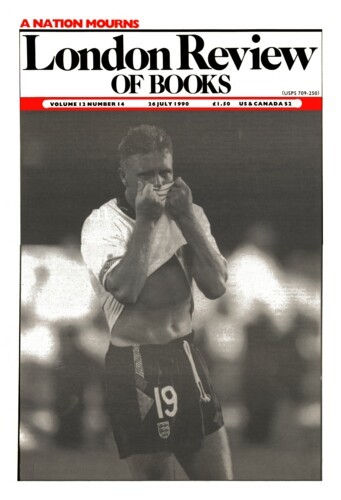

As had happened in the past, the team came together when an ailing Bryan Robson was reluctantly removed. England switched to a sweeper system of sorts, long resisted by Bobby Robson, with Wright at the back when he wasn’t at inside left, and they played very well for the rest of the tournament. It was possible to feel that it was the players who were playing well, and that Bobby Robson had been left behind to make statements to camera. Gascoigne was more than anyone the secret of their success. By general consent, he was the superlative England player. His detractors in the press did not entirely give up, though: late in the day they were still preoccupied with his development, his potential, his mistakes, his personal shortcomings. Patrick Barclay even managed to jeer at his conduct when he was awarded a yellow card for a legitimate tackle in the semi-final game against West Germany – which England were unlucky to lose, at the penalty shoot-out. The tackled player rolled about in a piece of German theatre that might have earned him a place in Goethe’s Walpurgisnacht, the German officials sprang to their feet and to the touchline in horror. The card meant that Gascoigne would have been unavailable for the final had England survived, and before the penalties were taken he was seen to weep.

Gascoigne’s conduct has exercised a colossal fascination in this country and in others. After the narrow quarter-final victory against Cameroon, he exulted and gave Bobby Robson a kiss. The camera followed the boss as he walked off and was observed to wipe away the kiss. Or he may just have been rubbing his cheek. There was no knowing. But it was difficult not to cherish, at that moment of drama, the thought of the putdowns to which the player had been subjected. His power and invention transfigured England’s contribution to the World Cup, and his overflows of feeling were part of it.

He was a highly-charged spectacle on the field of play: fierce and comic, formidable and vulnerable, urchin-like and waif-like, a strong head and torso with comparatively frail-looking breakable legs, strange-eyed, pink-faced, fair-haired, tense and upright, a priapic monolith in the Mediterranean sun – a marvellous equivocal sight. ‘A dog of war with the face of a child,’ breathed Gianni Agnelli, president of the Italian team Juventus. He can look like God’s gift to the Union Jack soccer hooligan, and yet he can look sweet. He neither fouled nor faked; nor did the team, which won the tournament’s fair play award. He is the frog that turns into the prince every move he makes. Many may flinch from his practical jokes and his scuffles outside discos; I’m not sure how well he’d do on Any Questions or in the House of Commons; he is sure to suffer from the intensified media build-up and cut-down that awaits him. But at present, in his early twenties, he is magic, and fairy-tale magic at that.

The punishment of his German tackle was one of a number of calamitous misjudgments on the part of referees. The policy on violent play reflected a welcome determination to deter, and it succeeded: this was not a violent World Cup. At the same time, there was gross over-reaction from several referees, too few of whom could tell the difference between a foul and a performance. Too many players were sent off for nothing. Too few of the later games were settled by decent goals. Two episodes stand out: the Rijkaard foul and the Klinsmann fraud. When Holland played Germany, the Dutchman Rijkaard felled Völler and then spat at him, twice. Throughout the episode Völler did nothing except avoid a collision with the Dutch goalkeeper. And yet he was sent off, along with his assailant. In Germany’s quarter-final match against Yugoslavia Klinsmann squeezed between two defenders and tumbled harrowingly, winning a place for his team in the semi-final with the penalty that was awarded. Ron Atkinson, who showed some jolly turns of phrase on television, reported: ‘I’ve just seen Gary shake hands with Klinsmann – it’s a wonder Klinsmann hasn’t fallen down.’ Atkinson, however, was also among the many exponents of the bottle theory, which says that foreigners don’t have what it takes, that dusky teams are mentally unsound, dusky goalkeepers suspect on crosses. It was a theory that had to struggle to deal with the evidence presented by Egypt and Cameroon.

Germany were never the team that British scribes made out, and there was some more of their theatre in the miserable final against Argentina, which had its own harrowing diver and roller in Maradona. Argentina finished the final two men down, for disciplinary reasons, but Germany never did manage to beat them. It was fitting that the game should have been decided by a somewhat generous penalty award. The scribes and commentators rarely tired of mentioning Maradona, the ‘greatest player in the world’, who might or might not be in his cortisoned silver age. He has never, in my view, been the greatest player in the world, and no one else has been either. He still has his tricks, and his broad shoulders, he delivered some inimitable balls, and he badly wanted to win. But he was outclassed in the tournament by a cadre of others, including Haji of Romania, Baggio of Italy, Milla and Gascoigne.

It was said by an expert that Italy bottled out against Argentina. Their ‘temperament’ couldn’t take the ‘pressure’, according to Liam Brady – a surprising opinion from an excellent player who had actually played in Italy. The fact is that they drew with Argentina, deserved to win, and only lost out at the penalty shenanigan after extra-time. Italy against Uruguay was perhaps the finest game in the Cup. Not for the first time in the history of the game, Uruguay proved a very hard team to beat: this was a tough, intimidating side which contained two or three of the most accomplished players in the tournament and half a dozen of the most cunningly hostile. Italy’s victory was a victory for football. But the game gave no joy to the journalist who wrote about it for the Independent. The Italians hadn’t played, had been anxious and upset. Here, too, they had bottled out. It was just as well that his readers knew the score and might have seen the game for themselves.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.