When I hear talk, as I have done recently, of another review of the Diplomatic Service, nothing occurs to me. This paralysis is induced by a premonition of intolerable tedium. Such a review, I suspect, would be a replay of what happened a decade ago in the Think Tank review: an exercise in evasion designed to conceal more than to illuminate Britain’s real problems. These problems were and remain almost entirely domestic in origin. When you are not prepared to face up to the underlying questions, you invent bogus ones and appoint someone to examine them. That was the way of the last Labour government. It is not supposed to be this government’s style.

The examination and re-examination of Britain’s representation abroad is such a long-running and tiresomely predictable saga that you could make a television series about it. The FCO Revisited, perhaps? Popular success is guaranteed. The old props are still available from previous productions: Gilbert Scott’s Foreign Office, Lutyens’s architecture in the British Residence in Washington, or Pauline Bonaparte’s Residence in Paris, now the home of the British Ambassador, are more than adequate substitutes for Brideshead. Ex-ambassadors are in permanent supply to break decades of enforced public silence with steely letters to the Times in defence of the Service. Cartoonists are on permanent stand-by to re-sketch those gentlemen in pinstripes and bowlers whom nobody has ever met but whose image is deeply cherished by all. The abovestairs life in an overseas embassy could yet again be poignantly contrasted with real life in Liverpool. Envy, nostalgia, anti-élitism, a touch of class-battling – it could be just like old times.

There is a real review to be conducted of Britain’s diplomacy, but it would not be much fun. It has nothing to do with the staffing levels of embassies, the cost of entertainment allowances, or whether the Pushtu service of the BBC should be reduced or increased by half an hour a week. It would be a fundamental reappraisal of the function of defence and diplomacy in the post-Cold War era, for a middle-ranking power whose economic recovery is as recent as it is precarious, whose educational and cultural levels remain low, and whose main conurbations – which already include some of the most desolating cityscapes in Europe – are becoming environmentally asphyxiated. Such a review would have little attraction for government, and limited popular appeal. The ingredients of an old-time British social comedy are simply not there.

Over the decade since the last pseudo-review of the Foreign Office, British diplomacy has continued largely as before – if anything, rather more so. This diplomacy has been broadly successful for two reasons: one positive, one negative. The positive reason is that the Conservative Government’s boldness in tackling internal problems has earned us new international respect. Mrs Thatcher is the only prime minister I can recall whose overseas reputation has been based more on domestic achievement than international activism. The more negative reason for our relative success overseas is that events have fortuitously helped us to maintain a high diplomatic profile – with its ever-present risk of reinforcing old illusions about our real place in the world.

Lancaster House converted a long-standing and abject foreign policy failure into a dazzling success, so reviving our reputation for diplomatic genius. Argentina provided us with a small, controlled war we could not afford to lose and in fact won in style. During the same decade, the Cold War not only persisted but went through a phase of heightened tension. This was not sought by Britain, but was a boon to us nevertheless. It enabled us to display ourselves to our best advantage: by an admirable combination of toughness in defence and sobriety in diplomacy we maximised our influence in Europe and America.

Even our battle with the Community enhanced our standing: we were seen as a renascent power determined to secure its rights and objectives. Indeed we were persistently urged by pro-Europeans in this country to use our new prestige to seize the leadership of Europe. All this was dizzying stuff for the electorate. What could be better calculated to raise the national spirits than a government holding the flag high in the face of the evils of Communism, the murderous follies of buffoonish Argentinian generals, and the intrigues of the perfidious French?

And now it is gone, all gone. In a matter of a mere few years life itself has shot most of our international foxes. The most fundamental change has been in the East. The Communists have thrown in the sponge and left us bouncing about in the ring looking for an opponent. With the exception of the Middle East, where British power and commitments are fortunately highly circumscribed, Third World heat spots are cooling fast. As for Europe, the big problem has been resolved with spectacular finality. The notion of British leadership of the Community – always a fond figment – is now as hollow an illusion as that of a permanently divided Germany. There can be no debate about staying or leaving. All that remains is the long haul in Brussels.

The question naturally arises: what is British defence and diplomacy for now? In any other sphere of life, when demand for your product collapses for reasons entirely beyond your control you don’t try to drum up new custom: you wind the business down and go into something more profitable. Of course it is not quite as simple as that. Clearly there is work to be done to develop a security system to replace the balance of tensions that held Europe in equipoise for forty-five years, and there are risks of instability meanwhile. European diplomacy will continue for the indefinite future to be a feast of summits and councils and manouevres and dramas over the desirable degree of political and economic integration, or of phoney wars over mad cows or soft cheese. Clearly we have residual commitments in Hong Kong or the Falklands. And clearly there are concerns about new sources of tension – Muslim fundamentalism and the rest of it.

Nevertheless, there is a disturbing feeling about that something irreversible may be happening in the world, and that it is not to Britain’s advantage. Simply put, the fear is that as geo-economics take over from geo-politics, Britain’s long day in the international sun may be waning; that we shall be forced to spend less time basking on summit slopes and more time digging the national allotment. With the passing of the Cold War and the rise of a new Europe, a sense of hope is coupled, in the case of Britain, with a palpable sense of loss.

We have done a pretty good job internationally since 1945. But a lot of our post-war prominence has been artificial. For obvious reasons the Cold War inflated our international influence. We chose to inflate this still further by shouldering an artificially large military burden compared to that of our allies – except for the Americans. This in turn led to an inflated domestic defence industry. On this we based artificially high defence exports, where we enjoyed an artificial competitive advantage because of the post-war exclusion of the Japanese and Germans from much of the market. With Germany politically dwarfed by division, Britain, like France, loomed artificially large in Europe.

A few episodes apart, our post-war foreign policy has consisted of a series of brilliant improvisations which will earn us commendation in the history books of the future. Given the limitations of our power, we have done marvellously well in foreign parts, though not nearly as well in Britain. And now that some form of peace may be upon us, the cost and penalties of victory will become increasingly apparent. On the day last November that Mr Gorbachev in his wisdom decided against moving a single one of his 380,000 soldiers onto the streets of East Germany in defence of the Communist regime, a long and distinguished era of British diplomacy came to an end. The fact of it is that for the second time this century, as far as Britain is concerned, the Great Game is over.

The impact of the changes we confront is so great that there will be a psychological disinclination to absorb them. Prime ministers and foreign ministers understandably relish international prestige and influence. Parliamentarians enjoy announcing their views on foreign policy, not just to their electors, but to notional constituencies abroad. The reader of the Sun finds the symbols of international prestige, whether summits or soldiery, a powerful stimulant to his sense of national virility.

Editorialists in our more reflective press like to think that their thoughts on this or that aspect of foreign affairs raise gentle thunder in Europe and maybe even ripples on the surface of the Potomac. The notion that what Britain collectively thinks, says or does about the great issues of the times may suddenly matter less today than it did yesterday will not be easy for us to accept. Recent events at home will not make it easier. As ill luck would have it, the reduction in our role abroad that will follow the collapse of Communism has coincided with a distinct slackening of the will to pursue the long-term goal of the economic and social regeneration of Britain. The twin peaks of our new prestige in domestic and foreign policy were reached some time in the mid-Eighties. Since then, the descent has been sudden and steep. Only a few years ago we were seen as a case of near-miraculous resurrection, as a model of post-socialist and post-imperialist reconstruction sustained by a home-brewed elixir of energy and enterprise, as a country whose prime minister represented not so much a nation as a Hegelian world spirit.

From today’s vantage point we can see that both the extent of the internal recovery and the solidity of our new influence abroad were a little oversold. A good deal of the overselling was done by Britain herself. Our advances at home have been startling, but are still far from complete or assured. However dynamically led, countries do not throw off legacies of complacency which reach back a century in a mere decade, however action-packed. If a single illustration had to be selected of the persistence of the sort of mentality that got us into trouble in the first place, I would choose house price inflation. That great bubble which is now being so painfully pricked reminded us of an equally painful truth: that as soon as you put money into an Englishman’s pocket he still has a tendency to invest it, not in his own industry or enterprise, but in the sterility of bricks and mortar, convinced that wealth will accumulate without risk or exertion.

That there have been increments in productivity is undeniable. But enterprise is still not our ideal – merely an inconvenient necessity thrust upon us by a socially inferior and crudely materialistic world. What we still secretly yearn for is a rentier idyll, semi-oriental in its passivity: to sit in a sort of opium haze in a house whose price rises effortlessly and exponentially over our heads while we watch not over-demanding programmes on a Japanese-made TV, with a prunus nipponica in the garden and a Nissan outside the front door. It seems to be taking a little longer than anticipated for us to understand that this reverie is not financially sustainable. A glance at the trade balance or the interest and mortgage rates shows that we have not learned it yet.

It cannot be said that we have taken this simultaneous decline in our domestic and foreign standing with any excess of grace, though we are now showing a little more dignity in recognising the inevitable in Germany than we showed a few months ago. In our dealings with Nato and the Community we seem to be recovering our poise. With so much confusion over the future of Nato and so much hot air to be dispelled over the development of the Community, there is no lack of outlets for British pragmatism and purposefulness.

Diplomatic resourcefulness alone, however, will not be enough to secure our objectives in a world undergoing a benign revolution. When wars finish, reconstruction begins. New hope is not confined to Eastern Europe. For Britain, too, the end of the Cold War offers a chance of new beginnings. The first thing we should do is to re-examine old vocabularies.

The first function of a state is to maintain its security. What is the military threat to Britain today? I do not say there is none, or that we can dispense with nuclear weapons, our navy, army and air force. But like the compilers of the Ministry of Defence estimates, I find it embarrassingly hard to define this threat.

What is happening is that concepts of security are changing, as is the notion of threat. How is Britain’s security to be assured in the future? Through the most powerful military force in Europe, which we cling to even today? Or through new forms of security based on ever higher levels of education and enterprise? How are we to secure and defend our national identity in the future? Through missiles we are no longer quite sure where to point? Or through a stable and civilised society, a modernised democracy – not least local democracy – and a common national culture? To speak of the need to enhance the environmental security of this small, over-populated, sadly scarred and so often unbeautiful island is to labour the obvious.

As the threat from the East recedes, other non-military threats will loom larger. The economic threat posed by nations with larger, better-trained and more energetic workforces than our own is one. The threat of the dissolution of the family is another. The threat of a trashed society, trashy broadcasting, trashy newspapers, trashy values, a national past trashed by a trashy education system, is a third. Finally, there is the threat of drugs and nihilism. As the smoke of the Cold War recedes, the contrast between Britain’s international pretensions and stubborn domestic realities will re-emerge with renewed starkness. Reflect on the following facts. We are the poorest of the four largest countries of Europe, yet as a percentage of GNP we spend more than anyone else on defence. We have a large and skilled army on the Rhine and an army of semi-literate unemployables at home. We have well-equipped forces to help us win wars which seem increasingly unlikely to happen, while we strive to win contracts with an under-skilled and under-educated work-force. In science, we spend as much on defence as on civilian research. Our frigates are swift and gleaming: our transport is slummy and slow. We have a fine fighting force with no enemy in sight, and a rotten public transport system with no train in sight either. In military life, smart young men are promoted to positions of responsibility by their mid-thirties; at home, essential services are managed by gentlemen of comfortable age and habits who have risen inexorably to their positions on the tide of time.

When it comes to staffing our embassies abroad, we are highly selective. Only the best will do. In staffing our schoolrooms, we take on anyone who is willing to do the job. We spill ostentatious tears over the lack of opportunities for the oppressed in South Africa, yet we tolerate educational apartheid between the state and private sectors in Britain. The Victorian staircase of the Foreign Office is expensively re-gilded to delight the eye of foreign ambassadors, while our shabby schools are administered from a squalid Sixties building on the wrong side of the river. Our Foreign Secretary vaunts the advantages of the English language to the benighted peoples of Eastern Europe. Our own teachers decline to teach grammar on the not unreasonable grounds that they have never learned it themselves. Despite its recent concessions to vulgarity, the World Service of the BBC still broadcasts programmes that would be thought too demanding for domestic consumption. Maybe it is because so much of our language, literature and culture have become for export only that Britain is becoming the thick man of Europe.

The purpose of these allusions to our domestic inadequacies is not to deride the need for a competent diplomatic service or a sensible level of defence. The residual threat to Britain in Europe will only disappear when the Soviet Union becomes a stable democracy. For that and other self-evident reasons I favour the retention of nuclear weapons and an adequate fighting force. What I am suggesting is that we should be thinking in more radical terms than we have since the war about the new meanings of defence, diplomacy and security.

Our first reaction to the outbreak of peace was to try to pick a fight with Germany, and to insist that whatever happened, we must keep our guard up. ‘Keeping your guard up’ is a handy little phrase. I have used it myself. It is often all you get time to say during in-depth discussion programmes on television. It has a nice ring of instant wisdom to it. It goes down well with everyone because nobody knows what it means. How much of a guard should we keep up? And to guard against what? In nuclear terms I can see the argument. The actual or potential existence of these weapons in the hands of others could still imply a threat so extreme that we must keep them while we work for their final elimination. But in the far more expensive conventional field I see no rationale for Britain maintaining anything like its present levels of forces.

Let us imagine that the old order were to be re-established overnight in Russia: even that would pose a much smaller threat to us than existed before. Only a madman in the Kremlin would attempt to re-conquer Eastern Europe, and the conventional threat to Western Europe came chiefly from Soviet occupation of these countries. There is a fundamental contradiction in the proposition that the Warsaw Pact has all but disintegrated, and that we must keep our guard up against it. Are we to continue to spend the highest proportion of GNP in Europe because of the threat of nationalist conflict between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, Croats and Serbs, Romanians and Transylvanians? I am as aware as anyone else of the difficulties of predicting what will happen in Eastern Europe. But simply saying that it could all go wrong is cheap wisdom. Far more demanding is to prepare ourselves against the disturbing eventuality of some form of peace.

Ten years ago our present prime minister came to power because she was prepared to confront the country with unpalatable truths. She was quite right to do so. We were – and to some extent still are – an indolent, complacent bunch whose airy assumptions of God-given rights to this and that are based on a uniquely disastrous mixture of a socialist-induced sclerosis and a historically-induced sense of effortless superiority. Now there is another truth to tell the people. If we succeed in getting anything like a peaceful new order, the going for Britain could become not easier but tougher.

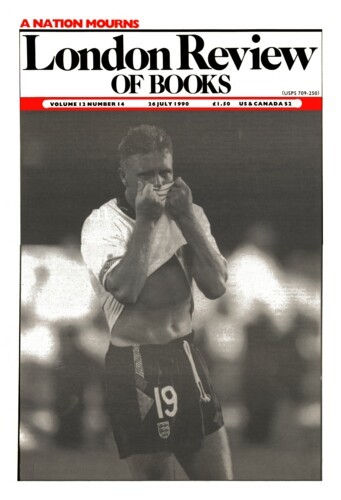

It will not be an easy message to get across. An imaginative and constructive approach will be needed to get people to understand that the good life and, a proud, prosperous and influential Britain cannot be bought by an overblown defence establishment and indiscriminate public spending; that these things will depend more than ever in the past on our educational, economic and cultural attainments; and that we have not come to the end of a period of radical change but have hardly begun. The alternative is a country that simultaneously loses its will for self-reform and its empire of influence: a sour and shrunken island disguising its resentment at the new prominence of Germany under the shield of an imaginary menace, a country so insecure that it resorts, like our legendary football hooligans, to an aggressive insularity in order to sustain its sense of identity.

So what is the prescription, and what will it cost? I believe we should begin to plan now for a massive switch of resources from foreign to domestic priorities, and in particular from defence to education. That may sound a curious prescription from a Conservative Member of Parliament. If I were addressing the Commons there would at this point be a chorus of ‘hear hears’ from the Labour benches. But there are two fundamental differences between what I am suggesting and what Labour have been asking for. Labour wanted to run down our defences and abandon our nuclear shield when the threat was immeasurably greater than it is today. The second difference is that when Labour talk of education spending they not only divorce cash from quality: they are pursuing defunct concepts of egalitarian uniformity now abandoned by socialist regimes, in so far as they had ever adopted them. They are talking about hand-outs to their political clients in the Unions from which no education benefits would spring. I am not interested in buying peace with the Unions. What I am talking about could involve a full-scale confrontation with these Unions and with the dons’ unions too. You might say that we have been through that before, but what I am saying is different. I would be ready to increase public spending on education by roughly a third. But I would not inject a single penny into our schools or higher education unless it could be shown that the result will be higher standards.

We need a system of nursery education for all – not just the rich and privileged. But it must not be founded on old-fashioned sentimental principles of all play and no effort or discipline. We need better pay for teachers: but some teachers need to be fired as part of the bargain, there should be much more selective recruitment, and the highest pay should go to science and technology teachers, who will always be most in demand. More should be spent on equipping classrooms: not by improvident local authorities but by self-managing schools. Higher Education should be expanded, but with no sacrifice of quality, and students should contribute to the cost. And as in the schools, there are dons to be bought out too.

The cost of all this must come from defence. Now I have no illusions about the peace dividend. It will take time to come through. Rationalisation costs money in the short term. There will be damaging repercussions for the defence industries, and there will be unemployment and retraining costs there too. But we should be thinking in terms of slicing back Britain’s defence spending by something of the order of a third to a half just as soon as this can be justified by disarmament prospects. As a historical overspender on defence, Britain is entitled to a peace dividend, and a big one, whenever practical. It has just been announced that the Government has embarked on an overdue review of defence. Yet some will say that my proposal for running down our defence effort is both dangerous and defeatist. My first reply would be to ask whether they or their children have attended state schools? My second would be that it would be dangerous and defeatist not to take radical action to adjust to a radically changing world.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.