Good writing, in prose or verse, can seem a sort of visible distillation, brandy-like, of the anima vagula blandula, the tenuous and transparent daily self that produced it. Another kind of good writing does not establish itself as involuntary personality, but as something the writer is just very, very good at doing. Such a dispossessed fluency seems available to everyone with a flair for catching a fashion. I suspect that a lot of people spellbound today in the intergalactic gameyness of an Ian McEwan novel feel that, yes, this is the thing – I could do this if I had the idea or the time, or, well, the talent. Good writing in this academic sense is, or seems to be, held in common.

‘Academic’ is a harsh word, implying as it does ‘creative’ writing, the thing that can be learnt on the campus, ‘the consequences’, as Philip Larkin put it, ‘of a cunning merger between poet, literary critic, and academic critic (three classes now notoriously indistinguishable)’. Gay Clifford was an academic, and by all accounts a brilliant and effective one, a lecturer in English at Warwick, where she was a colleague of Germaine Greer, and the author of a subtle and distinguished book of criticism called Transformations of Allegory. She was also a poet, who passionately wanted to be a poet, and to combine it with being a perfect teacher, researcher, lover, mother, perhaps even wife. A divine or sublime hubris here, risking the threat of the kindly ones, as Sylvia Plath did? Such seems to be the opinion of Germaine Greer, who in a vividly comprehending retrospect introduces her friend and these poems. The retrospective note is because Gay Clifford’s career, though not her life, was terminated in 1984 by a cerebral haemorrhage. ‘Her monument was less than half-hewn when she was forced to abandon it,’ Germaine Greer writes, ‘but it is more picturesque, more moving, grander, more sublime perhaps for that.’

Well, it is in a sense completed, in terms of local colour, by their relationship, by what is written about poems and author which the poems do not say themselves. These are apt to blur too easily into cleverness, into their own determination to be written, a lack of involuntariness which seems eventually their justification, palimpsests as they are of the will to make life glittering and hectic in the way Yeats (an admired and also hated figure) thought it should be. Pallas Athene must be in the straight back and arrogant head, even metamorphosed into a Sunday-supplement rushing and gushing. ‘Twice Gay grabbed the red can, sprinted across the carriageway and stuck her thumb out. Each time she was back in ten minutes. We were a hell of a team. After three days without sleep, when we and the Fiat were at last at Pianelli, Gay and I were still laughing at each other’s jokes.’ The struggle to be tremendous women, in the masculine sense, synergises with the violent pose of escaping such a role, and produces (as Germaine Greer implies) a new version of the crucified Andromeda, of Mrs Browning, Emily Dickinson, Christina Rossetti, struggling ‘to obey the peremptory demands of their own creativity within the limits imposed by our culture’.

This in the true and involuntary perspective behind poems that are often irritatingly with-it, sidestepping with Empson, pirouetting with Leda and that sexist swan,

helping you to imagine

yourself with a great, big

bill beating above that girl.

It may be that today’s escape route from fashion for male poets is into deprivation, for women into over-achievement and showing-off. Nonetheless, the poetry here is genuinely in the predicament, and seems the more genuine the more one reads it.

Out of cavern comes a voice

And all it knows is that one word: ‘Rejoice’.

That is the acceptable face of Yeats, and the poetry cannot but rejoice in acceptance/ rejection of male power.

All power just is that,

revealing indifference to

knowledge of those mastered.

Yet I take some delight in it all.

Man as swan, ‘a holy ghost that looks like Papageno’, expresses his ‘inexpressible silliness’, but can only be deflated in his own poetic coinage, the verbal ingenuity that goes with his sex.

the great

unpaid bill, history lately

falling about in laughter as

putting on swan-suit you

are caught with your trousers down.

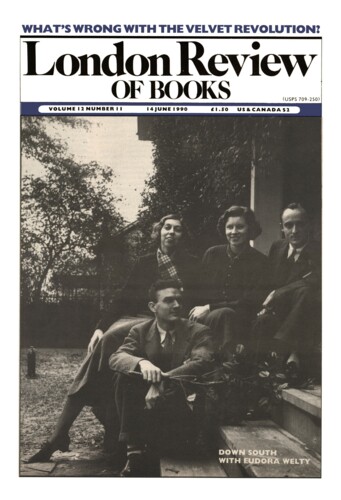

Men like to be laughed at by women – in poetry too. In deriding men this poetry is also obliging them, and this is where the individuality comes in and makes it more than a good academic exercise. Germaine Greer concedes that ‘wildness was what she was struggling for,’ and that ‘in the struggle to escape the bonds of her other-directed, examination-passing, deadline-meeting superego, Gay Clifford did sometimes descend to cant and rant.’ But there is neither in such notable poems as ‘The Departure’ and ‘Iphigenia in Aulis’, two taut constructs written on the same day and abruptly presented to Miss Greer, who had no idea that her friend wrote poems, but saw her in terms of ‘belongings in apple-pie order, labelled, folded, scented and camphored’, white damask napkins and ‘the heavy white china plates she always got from Antinori in Rome’. Lovers may have noticed these things too, more than their owner perhaps, as is implied in the very svelte poem called ‘Notes on the Characters of Men’, which is partly about the good lover who

doesn’t grudge, but sees she is setting down

in her own way what made him himself.

The male unrecognisingly adopts the properties of his woman’s being, and she concludes:

we are lucky to have lovers, do not put them on shelves.

I am made in their grace and care, and cannot rescind

My admiring and love of the difficult life they lend

to me and my kind. And I will not undo that love.

Dear, blighted Pope – no characters at all – ?

My muse is greater, loving yours and all.

Germaine Greer remarks that more people write verse now than read it. ‘Today’s hordes of DIY poets do not bother to read poems by other people because they so much enjoy penning their own.’ Not quite true, surely? Reading them, and writing them, can be the same sort of collective enjoyment. The rarity is to find something not like a ‘poem’, more like a person. Allen Curnow, like the later Auden, has the gift of making a contraption with a guy inside it, someone whose interest is not that of being a poet. Nor of coming from New Zealand. He has his own country, caught in a transparent gleam by such poems as ‘A Passion for Travel’. It’s quite often a question of a letter or two. The proof-reader ‘cancels the literal r and writes an x’.

A word replaces a word. Discrepant

signs, absurd similitudes

touch one another, couple promiscuously.

Travel muddles the alphabet and the image rather than broadening the mind.

After dark

that’s when the fun starts, there’s a room

thick with globes, testers, bell-pulls,

rare fruits, painted and woven pictures,

pakeha thistles in the wrong forest,

at Palermo the palm lily ti australis

in the Botanical Gardens, Vincento

in white shorts trimming the red canoe

pulled the octopus inside out

like a sock, Calamari! The tall German

blonde wading beside, pudenda awash,

exquisitely shocked by a man’s hands

doing so much so quickly

Calamari! Those ‘crystalline’

aeolian shadows lap the anemone

which puckers the bikini, her delicacy

Short of an exceptional moment, if only

just! In his make-do world a word

replaces a white vapour, the sky

heightens by a stroke of the pen.

In the text a full-stop has arrived after ‘delicacy’, but should surely not be there? Curnow’s lexical senses are wonderfully acute, seeming to fuse sardonically with popular images of travel, for what they conceal and metonymically reveal. Pen puckers bikini, and aeolian shallows sound harmonically, like Apollo’s lyre, while Marsyas is flayed or the cuttlefish eviscerated.

Although he is an Auckland academic who has won the New Zealand Book Award for poetry six times and is regarded as ‘a leading influence’ on his country’s writing, his world, like that of William Carlos Williams, seems uninterested in academe but absorbed by family, business and event. There is the poem on the skeleton of the Great Moa – an avian prodigy, long extinct – in the Canterbury Museum at Christchurch; a marvellous one on a 90-year-old mountaineer who had known

D. H. Lawrence? Terrible young man.

Ran away with my friend Weekley’s wife.

An elegy on the poet’s father keeps company with a long story poem, ‘An Abominable Temper’, about a 19th-century judge in the Native Land Court, writing to his daughter Ada. Enclosing three generations, it concludes:

This prophecy Allen shall make

for I live before his time.

In this context Shakespeare’s Fool does not seem tiresomely witty, but as natural as the few books, the Bible and the duelling pistols brought once from England, consulted for various workaday purposes in the new land, where there was no tongue or speech until Merlin utters his words to a later batch of the living, introducing ‘the landscape to the language’. That Curnow has certainly done, with so effective an accuracy that the place loses all self-consciousness.

In his introduction to Norman Cameron’s Collected Poems Jonathan Barker quotes a remark Auden made shortly before his death. ‘On hedonistic grounds I am a fanatical formalist. To me a poem is, among other things, always a verbal game.’ It depends, no doubt, on the impression it makes. The contraption (for Auden also spoke of those two entities) should draw attention not to itself but to the guy inside it. This was true of Cameron’s best poems, whose formality and finish must have won Auden’s warm approval. It is also true, although in a different sense, of Enoch Powell’s energetically constructed and always forceful verses. It is often said, and seems plausible, that poetry can surprise us into real attention only by the newness of its language – by not settling for old tactics and conventions. That is not always the case. The contraption, again, depends on the nature of the guy inside. Something was happening inside Powell, as inside Housman, which came out as it did, in a form suited to the temperament and the provenance, a form that can disconcert the reader by wiping out the writer’s self-consciousness.

But stretching out my hands to take,

I see her pattern on the Bread,

I see her shadow in the Cup;

and as I leave the hallowed place

and lift my heavy forehead up,

She greets me face to face.

Never mind that ‘hallowed’ seems too obvious a word: it is, as it were, corrected by ‘heavy’ in the next line. Cleanth Brooks observed of ‘In Summertime on Bredon’ that Housman should never have written ‘The mourners followed after,’ because the reader can get that without the poet’s help. But obviousness can be just the right foil for startlement. We know at once who the other person is in the Powell, though we know nothing about her, and she is not, needless to say, the Virgin Mary. Powell’s seemingly predictable poems are full of such surprises, and the invocations of friends dead in the war, in Mandalay or Johore, are not elegiac but spruce, fierce and comfortless.

Norman Cameron, like Powell, seems to have had the sort of temperament not much in evidence in the poetry that gets written today. He was a natural conservative who rhymed as instinctively as he played games, or, in his later years, wrote advertising copy (he created ‘Night Starvation’). A Scottish reserve and melancholy were illustrated in a spare sense that the best thing in life is to find nothing there. The proper reward of physical love is the comfort of emptiness where, as Larkin’s poem says,‘there are no ships and no shallows.’ This is conveyed by Cameron in a poem of four lines from a woman to her lover.

What is this recompense you’d have from me?

Melville asked no compassion of the sea.

Roll to and fro, forgotten in my wrack,

Love as you please – I owe you nothing back.

If poets no longer die so young, they can be cut off in middle age, a fate in a way harder when they have grown into richer and more confident working. Cameron died at 48, Gay Clifford had her disabling stroke a good deal younger. He preferred things to be nothing, she wanted them to be all: there is an irony in the way their poems join at moments, his finish and formality representing what was good to him, and her ragged flaunting display what she wanted to make of and seize in life. She needed babies and stylish spousal quarrels and reconciliations and the hurling of pots and pans. Realising this, Germaine Greer was rash enough to advise her lover of it, and received in token of dismissal a poem called ‘Finalities’. Estrangement was such that when Gay Clifford came to Italy she would pass within yards of her friend’s house ‘without coming up to hug the cats or see the garden’. The hint of an important distinction there, in art as in life. Some poets need to hug the cats; some don’t.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.