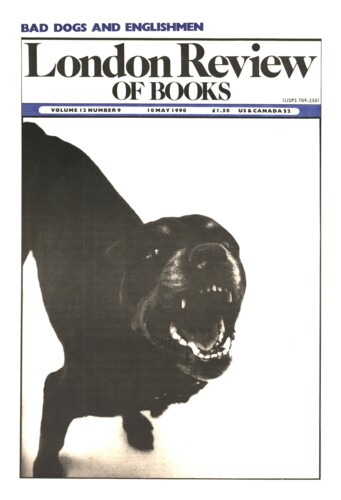

This small-brained animal, primed to hate, straining at the end of a short leash, is universally recognised as bad news. And the dog, his yellow-eyed, short-eared familiar, the killing machine, is not much better. The whole relationship is a mistake, a dangerous misconception, a perversion of actual needs. The dog as protector becomes the very thing that must be protected against: squat embodiment of threat. It is, of course, a truism that beast and man come to resemble each other, a couple wearied by compromise, tissue mapped by shared embraces. But even this specimen of folk wisdom is reinforced by repeated sightings. Something does happen. Jolts of electrified tension pass along the chain; defensive warnings are exchanged, atavistic fears. The man believes he is tethered to the heraldic expression of his own courage made into flesh. He is pulled forward by an intelligent muscle, a growling machismo. His phallic extension has achieved independence, and swaggers beside him: the dog is a prick with teeth. What the beast believes, I do not pretend to know. I leave that to Jack London.

My wife teaches in a borderland school. The place is invisible to those who cannot wait to escape from Hackney, who rush to their doom in a perpetual, honking stream, over the Lea and away into the comparative safety of Leyton, Whipps Cross and Epping Forest. The mulch zones in which inner city crimes are finally buried. They do things differently there. These are places people have chosen to escape towards. The school could be anywhere, but it happens to be in this lost settlement, hiding in the shadow of the Hackney Hospital, with its demented towers and abandoned wings. This is where you finish when the mind snaps beyond all hope of healing. All the unsolved problems have rolled down the hill and stuck, because they can go no further. The school yard is surrounded by a storm-fence to keep out the less determined and more visible spectres of rage. In the mornings – as the children straggle in, with parents, sisters, grandparents, keepers, or alone – the fence begins, unemphatically, to resemble the OK Corral. Pit bulls, denied access to the yard itself, are tied to hitching-poles. They stand, stock-still, gleaming bronze in the pale sun, flanks heaving, staring with eyes of inner anguish at these potential feeding-grounds. The dogs confer status even at the bottom of the heap. And this is where status is most needed. There is not much else. The pit bull is twinned in desirability with the possession of a satellite disk, if not the rancid channel itself. These hideous shields, each one representing a dog’s head, creep like malign barnacles over barracks of guttered experiments in public housing. Nobody has yet marketed a mock-Georgian satellite disk, decently rusticated, with pseudo coat-of-arms.

The dog and the disk: they hang out together like a pub sign. The one announces the presence of the other. The dog protects the disk, and also basks in its addictive glow. The disk, if activated, feeds liquid Sun, sick light; dopamine substitutes induce a paranoid trancestate, in which the only possible reaction to such selective inertia is a howl of suppressed rage, fire images of violation and urban destruction, apocalyptic seizures. We begin to ‘see’ dogs everywhere. And these dogs we have called into being begin to see with our eyes. But the hubristic expense of keeping such toys is crippling. Midnight flits are the norm. Puzzled children move school repeatedly, as dog and television are loaded onto a symbolic handcart, here masquerading as a respectable motor, paid off to the height of the hubcaps.

Everybody has their favourite pit bull story: stories that pull the community together, like doodlebug yarns in wartime. The Cypriot tailor in Dalston Lane, who still operates in the jaunty ambience that sent the Krays sailing to their fate in schmutter that made them look like Romanian secret policemen dressed for a perpetual wedding, recalls the incident in a decommissioned shop guarded by a pit bull. ‘Credit where credit’s due, he gave her fair warning.’ The police wandered across the road in response to unexplained ‘noises’. The dog had been in there for a week or ten days, unfed, unwatered; nobody seemed to know if the absentee landlord had done a runner, or if he’d been pulled in for having the wrong papers in the right place. But when the policewoman effected an entrance – brave, direct, as trained, bags of confidence, looking the beast in the eye, holding out her hand, palm upwards, for the lick of surrender – the dog sprang straight up and ‘took her face off’. They padlocked the door and came back later, when things were quiet, with a gun. Pit bulls will growl a warning, that’s the myth, but Rottweilers, guard dogs schooled in the concentration camps, go from drool mode to full frontal assault with no perceptible change of gear.

These stories have been around for a few years now. ‘Crazed Devil Dog Thrown Off Balcony’ is one that caught my eye in the Hackney Gazette, that estate agents’ pamphlet culled weekly from the Book of Revelation. Nkrumah Warren invited a couple of mates around to his second-floor flat for a cup of tea and a chat. His pit bull, a rare white costing £2000, did not altogether take to them. In fact, the wretch tore the trousers off one and tried to perform an unorthodox tonsillectomy on the other. This was taking an acceptable liveliness too far. Mr Warren locked the animal in the kitchen. The dog wasn’t finished yet, and hit the door so hard with his head that he reduced it to firewood. A serious business – damage to council property can have unforeseen consequences. There was nothing else to do. Mr Warren wrestled his treasure to the balcony and threw him over. The animal broke its back in the fall, and died. But the family did not give way to morbid thoughts. ‘I’ve got another,’ Mr Warren remarked, ‘who is absolutely fine with the baby.’

So this is a propitious climate in which to launch Scott Ely’s novel, Pit Bull, as a Penguin Original. And we are rapidly assured that it will be worth attending to this tale: the authorial voice is steady and confident. English fiction may be largely at the mercy of moonlighting journalists (auditioning for more copy in the Sundays), but the American Novel, line-edited until it shines, is safely in the hands of the Literature Professors, who are happy to remain on tenure while their raids carry them deeper and deeper into the badlands of popular culture. Scott Ely was ‘raised in Mississippi’, served in Vietnam, and is now operating out of Winthrop College, South Carolina.

Pit Bull is a book with plenty of space in it, holes in the dialogue, wide fields running down to the river. There is none of the fussy clutter of our febrile metropolitan product, none of that look-at-me-dad linguistic exhibitionism. Much is unsaid. And unsaid again. The form is laconic, spare, related to the post-Hemingway tradition of trash factory fiction. Research into the technical aspects of dog-fighting is convincing, without being excessive. The bigger the advance you receive, as Elmore Leonard has discovered, the bigger the research team you have to carry: until the novel disappears under its cargo of unassimilated information.

Ely’s pitch is pastoral, but sour. All the drift is towards the pit bull combat that provides the book’s inevitable climax. ‘It was when his eyes glazed over, a smoking white film over the gold, that he became dangerous.’ The language moves, and the chapters come in those nicely calculated lengths that can be read between tube stations: but I was left, at the finish, with a feeling of nostalgia for the psychopathic ‘humour’ of a Jim Thompson or the more exuberant culture spread of Charles Willeford’s Cockfighter. Fate should hurt, it should embrace more than a spoiled romance. The affair at the heart of this novel must be with ‘Alligator’, the stinking pit bull, the sunken mud creature, and not some whimsy about a hooker and her emerald earrings. The karma has to be rotten, incestuous, mad.

This is one of those father-son duels, where Dad wants to win the farm back by matching Alligator against a heavier dog, while Son wants to throw in with a cannabis-harvesting combo. Ely gives a precise account of the physical sensations of life in the Delta: crop-dusting, big breakfasts of ‘scrambled eggs, biscuits with honey from their own hives, fig preserves on homemade bread, and bacon’, long straight shimmering roads edged with cypress trees, creeks and swamps, fields of beans and cotton, the smell of pesticide. He tells us nothing we do not need to know. Every sensual ‘take’ drives the narrative forward. Symbols recur in a hallucinatory procession: the emerald earrings, the stench of the dog, the slow-moving river.

Pit Bull (the very title like a pre-emptive bid for video release) is one of those books you can’t help ‘casting’ as you read. It’s a pity about Warren Oates, but Harry Dean Stanton is still around, and it might be worth getting Dennis Hopper’s name onto the credits. Highway 61 runs north to Memphis and the soap-opera mansions of the Drug Barons. Ely has the good taste not to include a music track. But the space is there for Ry Cooder to fill. All the Method twitches, the signalled messengers of violence, are channelled into the loglike figure of the dog. He pants in the dirt, soaking it up. The pit bull was invented to receive and transubstantiate the bad will of men. The son masturbates Alligator, under his father’s instruction, in order to catch and preserve the champion’s sperm, his cloudy valour. This cracker Cerberus will, posthumously, save the land when he dies in the pit: a solemn Maileresque conceit on which to let down the curtain. ‘Nothing remained but a milkshake slush.’

The division of temperaments that runs through Pit Bull (Dog-Fighting as traditional, manly, independent and Cannabis Cultivation as new-fangled, feminine, internationalist) also spills over into quotidian Hackney life. This area gets more interesting every day. From my kitchen window I look back on the ranks of botched utopian fantasies that make up Haggerston’s various estates: a geological survey from Late Victorian charity, through Thirties kitsch, to the desperate and petty corruptions of Sixties socialism. The windows are grilled, corrugated sheeting is nailed over the doors of unoccupied properties. The debate has moved onto the walls of the buildings themselves, making them into capitalised nursery books of keening despair: ‘Fuck the rent,’ ‘How much longer must we live here,’ ‘Hillcot House salutes Volunteer Bobby Sands.’ There is an endless procession of supplicants climbing the stairs to the free-market pharmacist who operates his unlicensed dispensary from the top floor of a low-level redbrick block. Trade is brisk, but the dealers haven’t yet made it to their first pit bull. Their pride is an Alsatian, as old-fashioned on this turf as the Richardsons, the Nashes, or the Titanic Mob from Nile Street. Alsatians are like 12-year-old red Jaguars: they’re finished, guy. Good for nothing except barking, and bouncing impotently against the fences of scrapyards. Relics left over from The Sweeney. But the wholesalers – the tomtoms who pull into the trashed precinct in a personalised motor – they have a pit bull. They’ve got two pit bulls, twin heads wobbling in the window. Gold chains, leather hats: pumped to the limits of self-parody, the bosses in their glitzed company limo look like snuff-film extras. The wretched Alsatian slinks off to sniff at cigarette packets and to pee on a few steps. In the old days, apparently, around 1985, the drugs were carried inside the collars of the pit bulls. It took a brave man to stop and search one of those.

The only specimen I risked stopping to take a look at was panting, at ease, unprimed, on the flags of the canal bank in Bethnal Green. His opo had interested himself in what was going on across the water. The man had a razor-shaved skull and small flushed ears, mutilated by circles of gold, disappearing into the only fat on his steriod-abused body armour. The pit bull was a statue, with the yellow eyes of an alien life-form. I’m sure there has been a terrible mistake. These things don’t belong here. They come from another planet, another time.

The dog’s own ears seemed to have been stapled with black bootlaces. The needlework was amateur. A few flesh wounds festered and dried in the oily sunshine. On the far bank a man in a many-pocketed flak jacket was holding a rope into the water, from which bubbles rushed gratefully to the surface. They were searching the canal’s black mucilage for the weapon or weapons that inflicted ‘multiple stab wounds’ on Hector Anthony Slaly (aka ‘Mike’), whose body, tied in a blue plastic sheet, and weighted with a tool box, had been found on the previous afternoon. The victim lurked, half-submerged in the water, for between ‘one and three days’. The theatrical appropriateness of this location was self-evident: the gasholder blocking the sightline of the most recent riverside development, the convenient gap in the fence, the burnt-out van and scorched container. The horseshoe of Corbridge Crescent offered the choice of a dash for the Hackney Road, or a jolt over the cobblestones to Mare Street. An unpleasantly baleful atmosphere was enforced by the proximity of the watchful man and dog to this recovery operation. Nothing was happening, and was taking its time about it. I had to summon up all my restraint to eliminate discursive fictional connections: guilt by association. That is the effect pit bulls have on essayists. To report the affair at all was to become a nark in the service of the agents of ‘dirty realism’. Bill Sikes and his mutt looked fearsome, but they were no more implicated in the crime’s leisurely aftermath than I was.

But why, at this point in our culture, do we choose to invoke the dog, the ‘prime secret’ of Robert Graves’s druidic triad? Why, by granting it attention, do we need to indulge this elemental whose jaw, once locked, has to be broken open with a specially-contrived wedge? ‘The first beast was like a lion ... and they were full of eyes within.’ Eyes within: watchful, but not appearing to watch, always on guard. We have created a totemic animal we can openly hate, that hates back, that is hate. An animal bred and trained until it is ‘viciated’, as Romain Gary has it in White Dog, his case-history of a German shepherd schooled to kill blacks on sight. We evidently require some ‘viciated’ thing, powerful enough to swallow all the bile of our ‘entropy tango’. As in previous times of plague, we have begun to ‘see’ dogs as warnings: Padfoot, Trash, Shriker, Black Shuck, Pooka, or the Hound of the Baskervilles. They are messengers of death, dark familiars with ‘streams of sulphrous vapour’ issuing from their throats. They represent a broken taboo. They have been carried forcibly into the light, out from the jaws of hell, by a new Hercules, a robot of greed and stupidity. We grant the pit bulls visibility only when we ourselves are shrunken and tired, when we have given way to an irreversible sickness of soul.

‘Black Dog’ is a mood of suicidal despair suffered, most notoriously, by Winston Churchill, himself a kind of neutered bulldog, a logo for Empire, slack-jowled, growling, veins fired with brandy. The dog is the alchemical nigredo, black outside and white inside, like lead: the element that must be transformed. It howls in prison corridors to keep suspects under interrogation from their dreams. That howl can be heard without any dog being present. Pit bulls do not howl. Their silence is a greater threat. It is the pre-crisis state at which we have now arrived.

Our best hope, perhaps our only hope, is to identify, and name, the opposite of a dog, the pit bull’s contrary. We have connived at too much darkness, turned our backs on misjustice and abuse, judicial murder, social dereliction. We know more horror than we can absorb. A ‘dog’ is the term book-dealers give to their least desirable item of stock. There is no colloquial term, so far as I am aware, for the choicest desideratum. Even the map spurns its canine tags. The Isle of Dogs has always been perceived as an unlucky and tainted place. Pepys shunned it. Ben Jonson’s first play used it for a title; it landed him in prison. That squalid lingam of swamp attracts the meanest of our ambitions.

This contrary must have a special quality that, by its peculiar nature, will make it impossible to define. We must look for movement in the air, unexploited epiphanies of light. Whatever is not infected by touching the ground. A music. A tumbling hoop of maize and gold, birds’ wings, dust, pollen, linen, song. A ravished inattention. Whatever is incapable of being listed by a newspaper. Whatever remains invisible to the video eye. And if we do not find this thing, or set out in quest of it, we will remain as isolated as that prince among paranoids, Franz Kafka, when he brought his creature, K., to his conclusion, when he identified the futile and meaningless instant of death. ‘But the hands of one of the partners were already at K.’s throat, while the other thrust the knife into his heart and turned it there twice. With failing eyes K. could still see the two of them, cheek leaning against cheek, immediately before his face, watching the final act. “Like a dog!” he said: it was as if he meant the shame of it to outlive him.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.