Football, and football violence, go back a long way in this country, to a distant past of tribal conflict – family against family, clan against clan, ain folk against the world. They are to be found in the Middle Ages among the fighting families of the Anglo-Scottish Border, as George MacDonald Fraser’s book The Steel Bonnets makes clear.* His synonymous reivers, raiders or riders used to get off their horses and play the football that became soccer and rugby, and they were not afraid of a few fouls: ‘some quarrel happened betwixt Bothwell and the Master of Marishal upon a stroke given at football on Bothwell’s leg by the Master, after that the Master had received a sore fall by Bothwell.’

Fraser’s book, now reissued, tells a story that is worth attention at the present time. It tells how the Wardens of the three Marches on either side of the frontier did their equivocal best – for many of them were bandits themselves – to bring a semblance of order to the killing ground of the Border badlands, that centuries-long South Armagh, whose ‘hot trod’ anticipated the ‘hot pursuit’ of the 1980s. ‘Force was the only answer’ to the troubles, says Fraser, while also a stimulus to fresh troubles – until the time came for a genocidal pacification, ordered by none other than James I, and Armstrong said his last good night. Nationality counted for very little, compared with family. Perpetually at feud among themselves, a community of predator victims straddled the frontier, as did a population of the defenceless: ‘The poor and those unable to pay tribut to those caterpilers are daily ridden upon and spoiled.’

The frontier was, even by modern standards, an uncivilised region, and yet it was rather more than a battlefield, though Liddesdale came close to that state. It was in touch with flourishing literary cultures to the north and south. One Warden of the English East March, Lord Hunsdon, a fierce and effective commander, a hanger and a swearer, and a patron of actors, was destined to be in touch with Shakespeare: reputedly the son of Henry VIII, he was also, I notice, the keeper of the woman claimed by A.L. Rowse (after Fraser’s book came out) as the Dark Lady of the Sonnets. The ballads collected by Walter Scott contain wonderful praise – together with much that is more wonderful – of reiver exploits, of their boldness. But Fraser is sharp with Scott’s worshipful view of his ancestors. Scott and his minstrels forgot to stress that reiver practice was to rustle cattle, lie and cheat, to ride up in the middle of the night, with guns and lances, to lift the animals and belongings of some woman in the hills. There are no ballads about Isabell Routledge, a widow, who on 2 April 1581 was robbed by thirty Elliots, none of whom can have resembled the author of The Waste Land.

Fraser lists the warring tribes on both sides of the Border, and among them are the names Charlton, Milburn and Robson. These are the names of families still prominent in the Newcastle area, and they are the names of celebrated footballers in the English game since the Second World War. Bobby Charlton is richly descended: ‘I come from Ashington in Northumberland, my mother was a Milburn and, if that doesn’t make me a Newcastle man, I don’t know what does.’ He is of reiver stock, as lots of people are, and so is Bryan Robson, who plays like a warrior for moneymongering Manchester United, a team which has learnt to play with a scowl, as if they felt they were being robbed of the results to which financial outlays and impatient fans entitle them. Bobby Robson, the England manager, adores Bryan Robson, and has been willing to play him even when he was unfit, and to hide the fact: during one run of international games the team only began to threaten when the wounded soldier was finally and reluctantly rested. In the same way, Gary Lineker has been asked to run and run for his country, even when he was off-form and running in the wrong direction. Running and raiding are never bad, it would seem, even when they aren’t happening, let alone succeeding.

I once fell out editorially with the late Hans Keller over an article in which he had argued that Bryan Robson was an unsatisfactory player, and that the ethos of fire and sword and effort which he had been taken to exemplify was an illness of the British game. I thought that the denunciation of Robson’s martial arts had gone over the top. But I quite agreed with Hans about the disrespect, indeed the spite, which is regularly shown here towards the inventive and constructive player, who is never allowed a disappointing or even an unobtrusive game. Bobby Robson’s team had hardly left the field, after the recent defeat of Albania at Wembley, when he was disparaging the contribution of Paul Gascoigne, who had come on late in the game to score one goal and make another – admittedly against a beaten side: Gascoigne had been disobedient and had wandered about. Robson seems to like the player, who started out, as he did himself, in the North-East: but there was a wish to put him down, much as Glenn Hoddle was always being put down, before being driven off to France. I expect that the same outlook will see to it that the international career of Peter Beardsley, also from the North-East, will soon be reaching a premature end.

It is possible to feel that British football and the violent world we now inhabit are neither of them remote from the old Border badlands, where a ‘back-handed sword-cut delivered by a horseman at the head of a dismounted enemy’ was christened a ‘Lockerbie lick’. British football has been known as a hard game of raiding and running, tackling and intimidation. But there are plenty of players and spectators who know that there is more to the game than that. Without being soft touches – they have done better than England and Scotland in the international arena – the various Brazils and Italies have not been like that. And the best team in this country, Liverpool, has not been like that either, though you might have doubted it for a moment if you had heard their player Steve McMahon referring on television to how determined he had been to win the FA Cup Semi-Final ‘at all costs’. Since the Fifties, however, the Liverpool support, like that of most leading clubs, has had what Fraser’s book might persuade one to call an atavistic element of fans for whom the game is hard or it is nothing, fans for whom it is nothing but tribal and triumphal displays, and a category for whom it is a chance to beat people up. The idea has been to descend on the enemy place, the foreign place, in order to damage and insult it, to hold affrays and get drunk. On Saturday afternoons shops and pubs have had to be turned into fortresses. These are fans whose interest in the game of football has been slight, and whose activities can be ranged with the hazards to which we have had to become accustomed in an atavistic contemporary world.

Leader-writers have long been given to calling their activities by the name of football, and making them out to be even worse than they are: for a number of years I went to games at a London ground and never saw a blow struck. But there can be no doubt that ‘sections of the crowd’ are often poisonous, that these activities will be resumed, and will have to be resisted, when the present truce loses its charm, and that there are supporters who have had enough, who don’t want to listen any more, for instance, to black players and injured players being jeered at. One of the best things written about and around football is the poem ‘V.’ by Tony Harrison, first published in this journal, in 1985. The poem has scenes of desolation which include the desecration of graves by Leeds United supporters:

when going to clear the weeds and rubbish thrown

on the family plot by football fans, I find

UNITED graffitied on my parents’ stone.

It is the work of someone raised within the culture of football and the two sorts of rugby, someone who is not, like the leader-writers, above the battle and ignorant of it. This helps to account for the pathos in the poem – a pathos unobserved by those who were later to denounce it as obscene.

Football is itself violent, of course – my friend Richard Wollheim once broke it to me that he was unable to look at a game, for this reason. But it has always distinguished between an allowable and an alien violence, and the rules it has for that purpose generally work. None of the really outstanding players – such men as Bobby Charlton, Jimmy Greaves and Franz Beckenbauer – has ever been a fouler, and the British game is probably cleaner now than it has been in the past. Football is meant to be in some measure barbaric, triumphal, but most people want it to be an art as well as a fight. One of the beauties of the game, and of similar games, of the game graced by the Rugby League star Ellery Hanley, for example, is their conjunction of art and power, aggression and restraint. The best football is music to the eyes, and music, too, is full of force. I don’t imagine this has ever been held against it, though it is true that it seldom breaks your leg.

It seems to be agreed that something will have to be done to improve the football environment. Death traps will have to be eliminated, stadiums rebuilt and redesigned – which doesn’t mean replacing the old-style surging prole-pens with glassed-in executive boxes. Some of the money which is being spent on success – and in certain cases on the enrichment of shareholders – will have to be spent on safety, and the Government will have to require this of the clubs. Mrs Thatcher’s identification scheme has been deplored as unrealistic and outrageous. Is it? We all have to identify ourselves from time to time.

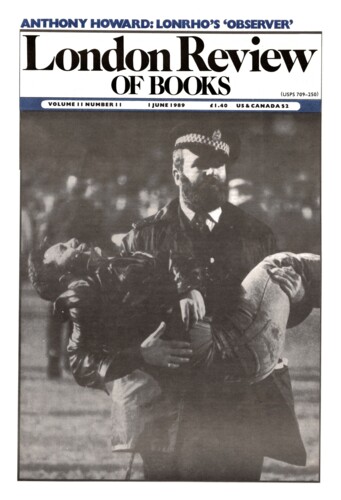

The present truce is a consequence of successive football-ground catastrophes. At Heysel Stadium in Brussels, Liverpool fans made an affray which resulted in many accidental deaths, and which was followed by outcries in Britain against the Belgian courts, with a horrible aggrieved solicitor to the fore. And then at Hillsborough the other day a mass of Liverpool fans arrived late at the turnstiles with the emptying of the pubs, and struggled to be let in. A gate was opened for safety’s sake, and they rushed, undirected, into the ground, causing more deaths. Blame was heaped on the Police, and there followed on television a protracted sentimentalising of football fans. Heysel was forgotten in the aftermath of Hillsborough.

In 1987, I was present at another such disaster. Hibernian were playing Celtic at Easter Road in Edinburgh. Late arrivals like myself, some of us drunk, boiled into a raging mob at the turnstiles. I remember one man holding up his small son and yelling about the danger to ‘weans’. The game proved to be a dour contest on a slippery surface in a gathering dusk. Sore falls and sad strokes were in the air; the 16th century battle of Solway Moss must have been a little like this. The elegant skills of Paul McStay were lost in the gloaming and the striving. Then a canister of CS gas was thrown into a terraceful of Hibernian supporters. Hundreds of them tumbled onto the pitch and 46 went to hospital. No word of explanation was heard on the public-address system. No one was subsequently charged, and the English papers gave the affair short shrift. Nor did the Government take any interest. It has taken more interest in privatising the water supply than it has in the series of disasters suffered by working people of which this was one. The Government has taught us a good deal about the violence of neglect and indifference.

Now that I am in Scotland, let me tell the story of another affray. A young journalist, a football supporter, who had worked on the London Review, went off to work in Glasgow. He liked the city; I seem to recall he was pleased that it had been designated a centre of European civilisation. Presently he was attacked in the street, and knocked unconscious, by two youths, who may have decided he was a foreigner. They were engaged in throwing him over the parapet of a bridge when the Police intervened. Whereupon they attacked the Police.

The other evening the same youths, apparently, were interviewed on television by a kindly woman, who enquired into their lifestyle. One of them was from a violent family. Were they sorry about the assault? Yes. They were sorry that it had put them in prison, an outcome which was blamed on the victim. We were left with the impression that they would be seeing about that when they were released.

This is a more lawless and a more atrocious society than it was fifty years ago. Nine out of ten poll respondents have said that that ‘it is more dangerous to walk the streets after dark than it was when Margaret Thatcher first took office.’ The Prime Minister believes in individuals and families and financial killings, and has no time for ‘society’. She also believes in law and order, but her government has entirely failed to reduce crime and allay fear. Can anything be done about this crime and fear? Our many prisons are overflowing. It would make a start if we were to try harder to face up to what our assailants are doing to us, in their various ways – to what they are doing to Ulster, for one thing, in the course of a long and contagious tribal war which the Government doesn’t know how to stop and which it can sometimes seem that it doesn’t want us to know about.

The present row at the London School of Economics deserves to be thought about in this context. The violence which tore a policeman to pieces in Tottenham was followed by what could be termed a violent prosecution and trial, which were followed by the violence implicit in the election, as honorary president of the Students Union at LSE, of a gangsterish character twice convicted of murder.

There is nothing to be gained by pretending that the human energies which give rise to violence are never attractive and never productive. Fraser points out in his book that Neil Armstrong made it with his Border blood to the Moon – a colossal violence, one could say, was involved in that feat. But nine out of ten must now be wanting to say something very different about the various forms of violence that there are in the world. I don’t know what television producers think. The ill-will and ill-temper depicted in their soap operas and dramas are worse than what there is of them in the streets, and have managed to make professional football look like a miracle of self-discipline.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.