Of the numerous biographical publications on the most problematic of 20th-century philosophers, Hugo Ott’s Martin Heidegger: Toward his Biography stands out as the most detailed and scrupulously accurate. But caveat lector: there is a great deal here that we would not think of as conduct becoming a philosopher or the academic profession in general. It cannot have been an easy book to write, and it is not an easy book to read.

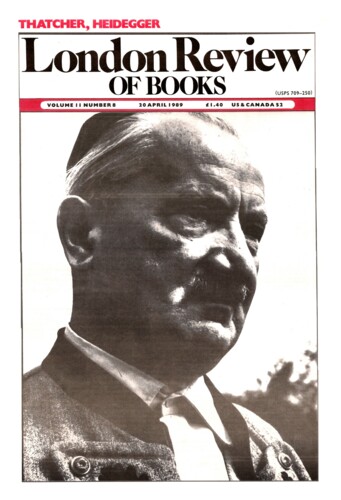

Hugo Ott is a social historian of 19th-century Germany; born in 1931, he teaches at the University of Freiburg, Heidegger’s own university. A conservative German professor of considerable standing, he has spent some twenty years collecting material and publishing articles on Heidegger’s life, and making himself unpopular with some of his colleagues in the process. Heidegger was born in 1889 in Messkirch, a small town in the Black Forest with a strong minority of Old Catholics, the son of a cooper and salaried verger; he died at the age of 87, having lived in four successive German states – the Kaiserreich, the Weimar Republic, Hitler’s Third Reich and, after an interregnum of three blank years, the Federal Republic. Ott is particularly strong on Swabian local and ecclesiastical history, and provides a vivid account of the youth and schooling of a poor Roman Catholic scholarship boy; it becomes clear that, but for an asthmatic heart condition, Heidegger would have taken Holy Orders. Heidegger at all times emphasised his spiritual kinship with fellow Swabians like Hegel, Hölderlin and Johann Peter Hebel (a writer of enchanting Alemannic folk-tales). He saw himself as a contributor to this tribal lineage, and associated his writings with it; his biographer reports on this powerful rural mystique, and is (as far as I know) the first author to do so fairly and soberly.

A professional historian of institutions, Ott works from an abundant array of sources. These include the very full archives of the town and university of Freiburg and several other Southern German cities, as well as the diaries, letters and private papers of most of Heidegger’s clerical patrons, and of his friends and colleagues. He has assembled evidence of Heidegger’s career from the local and national German press from the end of the First World War to the end of the Second; he has used all that survives (and a great deal does survive) of the correspondence of the various National Socialist ministries and party officials with and about Heidegger throughout the Third Reich; he has had access to the Allied archives relating to the French occupation of Swabia; and of course Ott has used, for what they are worth, the few statements that Heidegger himself made after 1945 about his own past. Not available to him were the archives at Marbach, on which an interdict sine die was placed by the philosopher’s family. There are more than twenty huge iron lockers of them, but it does not seem likely that the eventual disclosure of their contents will greatly affect our picture of the man and our reading of his work.

Professor Ott treats his subject with dignity and decorum, offers always the least damaging interpretation of Heidegger’s conduct, speaks of his own reluctance to give credence to the devastating evidence he has assembled, and occasionally falls into the slightly pompous conservative vocabulary of ‘sacrifice’, military heroism, and the like. He does this when writing, not about Heidegger (whose war experience turns out to have been markedly less heroic than he made out), but in praise of some of the colleagues (among them Jews) whom Heidegger calumniated. Thus the reader is left with the unfortunate impression that the dismissal of these men from their university posts after 1933 was particularly ignoble, and the fate of those who were not able to leave Germany particularly unjust: as though the humiliating treatment of Heidegger’s teacher Edmund Husserl at the end of his life were particularly heinous because Husserl, though born in Moravia, was a patriotic German, and it was known that one of his sons was killed and the other gravely wounded in the First World War. Such lapses on Ott’s part are rare, and they point to the difficulty of re-creating a world whose scale of values was very different from ours.

This is in no sense an intimate biography: Hannah Arendt’s name appears only briefly, the behaviour of Heidegger’s wife (who is still alive) is not dwelt on, and Ott has steered clear of what he calls ‘depth psychology’. However, his approach entails a limitation of a different kind. Since he is neither a philosopher nor a historian of philosophy, he offers no comprehensive appraisal of Heidegger’s many writings: Heidegger’s claim to be ‘the philosopher of Being’ is neither confirmed nor challenged in philosophical terms. He has little to say about the content of Being and Time, concentrates mainly on Heidegger’s writings after its publication in 1927, and mentions but does not enlarge on the lectures and essays of the last period, many of which are based on Heidegger’s readings of the poetry of Hölderlin, Rilke and Georg Trakl. All the same, he does quote abundantly from Heidegger’s philosophical writings, and his comments on these quotations are closely related to the biography. The strength of the book lies in the presentation of a life against the background of all those clerical, academic and political institutions which Heidegger succeeded in dominating or failed to put to his use.

The first and most important of these institutions is the Church. Heidegger’s Catholic background remained a determining force in his thinking even after he explicitly and vindictively repudiated it; indeed, of most of his writing it may be said that it is part of a theology without a God. This background accounts for Heidegger’s truly immense learning, but it also remains what Heidegger in a private letter called ‘a thorn in the flesh’ – the challenge against which he was determined to assert himself and his philosophical vision after he left the Church in 1919. Four years later, his Marburg colleague and Germany’s foremost Protestant theologian, Rudolf Bultmann, considered Heidegger to be one of the best Luther scholars in the country.

A very full account of Heidegger’s involvement with National Socialism makes it abundantly clear that he was neither a reluctant fellow-traveller nor (as his erstwhile friend Karl Jaspers believed as late as 1945) a nonpolitical scholar, a ‘child’ who got caught by the juggernaut of hideous political events. Heidegger became rector of Freiburg University on 22 April 1933. When he assumed office, he did not do so with the greatest reluctance and under pressure from a previous rector (as he claimed in his memoir, ‘Facts and Thoughts’ of 1945, and in his replies to the university commission which examined his activities later that year.) He contrived his election after having ousted his immediate predecessor (who held the office for a few days only), and as the nominee of the Prussian Ministry of Culture acting on the advice of the National Socialist members of the Freiburg University Senate. On the back page of the programme for the celebration of his ‘unanimous’ election (27 May 1933) appears the text of the ‘Horst Wessel Lied’ and the new rector’s instruction that – perhaps in view of the infirmity of some of his colleagues – the right hand should be raised only at the fourth stanza of the ‘Party Anthem’; this salute (the rector adds) as well as the call of Sieg Heil! should be understood not as signs of allegiance to the National Socialist Party, but as the national greeting of the New Germany. On 1 May 1933 Heidegger officially joined the Party, with great ceremony and with the ambition of becoming the Führer of the whole German university system. The precise nature of the reforms by which he hoped to bring about ‘the spiritual renewal of all life’ is not clear. What is clear is his intention of exacting the same loyalties and unquestioning obedience in respect of his decisions and decrees that Hitler exacted from the German state and throughout most of German society. This is the authority he asserts in the most notorious of his proclamations as rector, his Leipzig declaration of loyalty whose demand that Hitler be supported was publicised ‘worldwide’ a day before the National Referendum of 12 November 1933. (At this referendum, 95 per cent of the electorate voted in approval of Hitler’s policies and 92 per cent for the unitary party list for the new Reichstag.) No other single proclamation can have had such an effect on German intellectual life, none was so skilful in politicising the ‘metaphysical nation’ into craven conformity with the new regime.

The question of Heidegger’s academic and political standing is inseparable from that of his relationships with his teachers and friends, which appear to have been consistently self-seeking, vindictive, and occasionally perfidious. This is especially true of his dealings with the aged Edmund Husserl, to whom he owed his first university appointment at Freiburg, his first Chair (at Marburg), and whom he succeeded as Professor of Philosophy on returning to Freiburg in October 1927, after the publication of Being and Time in February of that year. Heidegger went to great lengths to collect evidence of some of his colleagues’ pacifist and ‘un-German’ past in order to discredit them in the eyes of the Party and influential civil servants, obsequiously retracting his accusations when he found that, for some expedient reason or other, they were being overruled. Even the polemics he conducted in his regular university lectures – as in his vicious attacks on the wholly defenceless Catholic philosopher, Theodor Haecker – had a political edge. Ott makes no collective judgments. All the same, it becomes abundantly clear that very few professors or students mentioned in his book – Rudolf Bultmann and Hans Gadamer are shining exceptions – took a stand against the denunciation, backbiting and time-serving which prevailed in the German universities of the Third Reich.

We have reached one of the points of complete incoherence between Heidegger’s life and his philosophy. Among the most impressive passages of Being and Time is the analysis of das Existential des Man, by which he means that aspect of our being in the world and with other people which is constitutive of inauthentic conduct, conduct legitimated by an appeal to ‘the average’ or ‘the everyday’, and summed up in such phrases as ‘one does’, or ‘they say’ or ‘it is thought that’:

We enjoy ourselves and take pleasure in things the way one enjoys them, we read, see and judge literature and art the way one sees and judges; but we also distance ourselves ‘from the crowd’ the way one distances oneself; we find ‘shocking’ what they find shocking. The One [or: the They] which is indeterminate and which is what all are, though not as their sum, prescribes the mode of everyday being ... Togetherness as such constitutes [besorgt] the average. The average is the pattern [Vorzeichnung] of all that can and may be ventured, it watches over every exception that asserts itself. Every kind of priority is silently suppressed. Overnight, everything original is instantly glossed over as long since familiar. Everything that has been fought for becomes readily available. Every mystery loses its power. This care of the average discloses once more the essential tendency of being in the world [Dasein], which we call the levelling-out of all possibilities of Being [Sein].

The simple fact is that the philosopher who has analysed inauthenticity more profoundly than any other, and given it its place not as an adventitious psychological phenomenon but as part of an ontological analysis of man’s being, his Dasein, is among its most astute practioners.

The attitude prevailing in the German universities of Heidegger’s day is unusual among the academic institutions of free societies. Any explanation of his conformity with it would have to begin with his frequently proclaimed conviction that he is in possession of the truth of the nature of Being (Sein which encompasses Dasein), or rather that he and he alone knows the right questions to ask, the right paths to take towards that supreme ‘ontic’ goal; that he is the first philosopher since the pre-Socratics to convey this truth, or at least to go along the paths to that truth; and that any criticism of his views amounts to an offence against the disclosure of Being, something resembling sacrilege. Hence his apparent assurance that questions involving lesser considerations – such as morality, loyalty, common decency and simple truthfullness – must be subordinated to his ‘ontologic’ message; and hence, too, the apparently boundless vindictiveness towards those who dared to oppose his decrees and decisions. This attitude of assurance is what Karl Jaspers singled out when, on being asked whether he would recommend Heidegger’s re-instatement as academic teacher in December 1945, he called Heidegger’s ‘Denkungsart in its essence unfree, dictatorial, communikationslos’, adding that he regarded this ‘mode of thinking’ as ‘more important than the content’ of Heidegger’s ‘political judgment’. The distinction is misleading. It was precisely Heidegger’s astonishing political judgment that Hitler’s National Socialism offered Germany (and Europe generally) the only chance of being saved from destruction by technology, and thus keeping open the questioning that really matters. The most direct public statement of the politics which sustain this ‘ontological’ belief is contained in the Leipzig proclamation:

We have broken with idolising ground-less and powerless thinking. We see an end to the philosophy that was subservient to it. We are certain that the clear hardness and workmanlike assurance of an unyielding simple questioning of the essence of Being is returning. The primordial [ursprünglich] courage either to grow or to founder in the encounter with Seiendes [the entities of being in the world] is the innermost motive of the questioning [performed by] völkisch science ... The National Socialist revolution is not merely a handing over of power presently at hand [vorhanden] in the State to another party ... but this revolution brings with it the complete radical change [die völlige Umwälzung] of our German being [Dasein].

There are other, equally repulsive assertions in the manifesto, which Ott may be excused from quoting in full.

Again, caveat lector: most of the major terms I have used are either an inadequate translation of the German, or ropey English, and probably both. Yet the meaning of the passage is clear: Hitler’s victory will ensure a return to the question of Being – the question which Heidegger alone is asking with the full seriousness it demands. I doubt whether anything Georg Lukacs wrote in his Stalinist days is as damaging as this passage, in which one and the same style serves both politics and philosophy: at its salient points this manifesto is couched in the diction which its audience readily recognised as the diction of Being and Time. This is language in its performative mode: a rhetoric which not only urges the identity between Heidegger’s ontology and Hitler’s politics, but which offers itself as a pattern and example of this identity.

Heidegger’s assurance of being uniquely in touch with Being led him to adopt tactics which Ott recognises as shameful, though he does not call them that. He does, however, illustrate Heidegger’s political activities in colourful detail. In one of the few hilarious episodes recorded here, Heidegger – a small man in carefully-designed peasant gear with, in later years, something of an embonpoint – is presented as the founder and leader of a National Socialist summer camp in which military training was to be combined with political and philosophical indoctrination, and which quickly collapsed in a welter of intrigue.

The skill with which Heidegger manoeuvred himself into positions of great authority is bound to make one doubt whether this ‘ontic’ belief was genuine; or, since questions of belief are notoriously difficult to answer, whether there was not at times an element of mental disturbance in this assertion of a self that is always right, always on the way to the ‘unhidden’ truth. Ott does not seem to share this doubt; or if he does, he is reluctant to express it.

Heidegger’s decision to resign the office of rector after twelve months had to do partly with the opposition of courageous colleagues, and partly with his failure to initiate the reforms for which he claimed to have sought the office in the first place. But he also ran into intrigues from ‘philosophers of Being’ in the government office presided over by Alfred Rosenberg, author of The Myth of the 20th Century. They launched an attack on him in the Party press, which included the claim that he was ‘the leader of a Jewish clique’. This of course was malicious nonsense. In fact, as Ott points out, Heidegger’s anti-semitism was not as radical as other writers have made out, and it was certainly not racial, though Ott also observes that whenever Heidegger acted on behalf of a Jewish colleague, he did so (as one generally did in German university circles) with the aim of protecting the name of German learning against critics of the regime abroad.

Heidegger mentions the massacre of Hitler’s myrmidons in the course of the Röhm putsch of 30 June 1934 as the occasion of his break with the Party, though he remained a member of it to the end of the Third Reich. He dates his disillusionment with National Socialism as the end of 1933, though he only resigned as rector on 23 April 1934 (not, as he later claimed, in February of that year), continuing in his office as professor of philosophy until he was dismissed by a tribunal set up in 1945 by the French occupation forces. His resignation (he later said) was caused by his discovery that the actual National Socialist Party and thus the Government of Germany had betrayed the ideals of the revolution which brought Hitler to power, and if he was merely mistaken in his assessment of those ideals, then clearly he had little to apologise for or to retract. Ott presents this notion of a Privatnationalsozialismus as the expedient fantasy it was. That Heidegger’s break with the Party and its ideology cannot have been as radical as he claimed is shown by a remark he made in the course of a lecture on ethics he gave in the summer of 1935. Attacking the contemporary ‘Philosophy of Value’, Heidegger likens it to ‘what is nowadays touted as the philosophy of National Socialism, but [this] has not the least thing in common with the truth and greatness of National Socialism’ – a phrase he altered in 1953, to read: but this ‘has not the least thing in common with the truth and greatness of the movement (to wit with the encounter between technology on a planetary scale and modern man)’.

When did Heidegger’s much publicised ‘turn’ occur? Since most of his wartime lectures remain inaccessible, it is difficult to date his change of mind reliably. Ott’s account of his post-war activities and proclamations includes what may well be Heidegger’s only reference to the holocaust, in a letter to Herbert Marcuse, one of his former pupils. Marcuse’s reproaches are justified (Heidegger writes in January 1948): he can only add that ‘instead of “Jews” ’ Marcuse’s letter ‘ought to say “East Germans”, and then it is equally valid in respect of one of the Allies, with the difference that everything that has been happening since 1945 is known to a world public, whereas the bloody terror of the Nazis was actually kept secret from the German people.’ But by that time Sartre and others saw to it that biographical disclosures should not stand in the way of a rehabilitation if not of the philosopher then certainly of his ‘existentialism’, even though Heidegger had long since rejected that label. In 1946 he was forced to retire from his Chair, but the decision was rescinded in 1950, when he was granted the status of emeritus and his teaching rights were re-instated. It seems that the University Senate had little choice in the matter. Enthusiastic audiences had welcomed Heidegger’s return to the rostrum well before that time; a lecture at the Bavarian Academy brought him the greatest acclaim of his entire career; his mountain hut in Todtnauberg, visited by Paul Celan in 1967, became something of a place of pilgrimage; and when, finally, a Russian philosopher wrote to him that in the Soviet Union, too, his reading of Hölderlin’s ‘lament for the absent gods’ was being accepted as a valid reading of the modern age, the murky past seemed forgotten, the rehabilitation complete. He died on 26 May 1976 and was buried, according to his wish, in the churchyard next to St Martin’s in his native Messkirch. The immense productivity of the post-war years remained unimpaired almost to the end.

Do we need Heidegger’s biography in order to understand his philosophy? In contrast to the writings of, say, Kant or Hegel, Heidegger’s work does not constitute a unitary body of thought that could be called ‘a philosophy’. We must certainly give central importance to the question to which he himself repeatedly returns – ‘Do we in our time have an answer to the question of what we really mean by “being”?’ – though we must take equally seriously his insistence that what is important is asking the question, and his harsh criticism of the false assurance of anyone who expects a simple, definitive answer. But even if we reject ‘the question of Being’ as meaningless and point to the forty pages (in the Introduction to Metaphysics) of grammatical and etymological by-play on the verb sein and the roots from which its various forms derive as evidence of its arbitrariness, we still cannot fail to recognise that the diversity of the areas of thought, experience and speculative hypothesis from which the question is asked, and the intensity and resourcefulness of the asking, reveal insights into our condition which are unparalleled in our time. These insights concern care, praxis, conscience, anxiety, death, historicity, the subject-object relation which philosophers since Descartes have postulated, and our ‘being-there’ in the world (Dasein), of which ‘understanding’ (Daseinsverständnis) is an integral part. And there is a prima facie case for some of these insights to be examined without recourse to biography.

This is what Hubert Dreyfus does in his recent discussion of ‘Husserl, Heidegger and Modern Existentialism’ in Bryan Magee’s The Great Philosophers. He begins by outlining Heidegger’s claim that the relation of thinking subject to thought object does not adequately describe our most common relation to things. What Dreyfus calls our ‘everyday masterful, practical know-how’, our ‘everyday coping’, proceeds by dispensing with ‘mental states like desiring, believing, following a rule, and so on, and thus with’ – what Husserl called – ‘their intentional content’. (This incidentally is the point at which Husserl became convinced that Heidegger had travestied his ‘phenomenological’ analysis.) Dreyfus goes on to describe the way Heidegger’s concept of knowing how to practise a particular skill presupposes our familiarity with the world in which we are placed, presupposes all of our Dasein. But this ‘knowing how’ proceeds without need of rational choices, let alone of the kind of thinking that has led philosophers to their doubts concerning the existence of the external world. By emphasising the habitual, unthinking disposition in which we take things and our use of them for granted, Heidegger relegates our conscious reflective activity to situations in which our skills don’t work because things go wrong, or to theoretical or scientific thinking, or again to an unsettling (unheimlich) search for a meaning to give our existence, a ‘meaning of life’; and our attempt to avoid this search is, for Heidegger, one form of our inauthenticity.

Dreyfus then identifies Heidegger’s ‘turn’: it occurred (according to this interpretation) when Heidegger introduced the historical dimension into the process he has been describing. Now rational choices become efficient choices, and efficiency, in our historical situation, is identified with technology, whose aim is the pursuit of contingent ends for no other reason than that they are technologically interesting and technically attainable. All meaning, for Heidegger, is and always has been contained in our Dasein, but if nowadays our Dasein (including our understanding of it) is determined by technology, all meaning is destroyed by nihilism. How is this vicious circle to be broken?

Heidegger considers two ways out. Dreyfus outlines one of these ways, which Heidegger calls Gelassenheit, and which Dreyfus interprets nicely as the appreciation of ‘non-efficient practices’ and ‘the saving power of insignificant things’; whether Heidegger would have recognised Dreyfus’s colourful Californian illustrations of this laid-back condition is another question. But what he doesn’t say is that Heidegger’s celebration of his désinvolture is the second (and later) of his proposed solutions.

The first leads to the political disaster Ott’s book describes. It is Heidegger’s briefly held but loudly proclaimed belief in National Socialism as the political system which relegates (or will relegate) technology to its proper sphere and thus opens the way to a valid, non-nihilistic meaning. If this system is seen as vouchsafing the return to ‘the simple questioning of the essence of Being’, so that what you have to do is give ‘the Movement’ your allegiance and support, then, clearly, an examination of the politics adumbrated in his philosophy becomes unavoidable, and their place in his biography unignorable: though, once again, this solution (which manages to be both ridiculous and monstrous) need not invalidate the earlier, ‘phenomenological’ steps in Heidegger’s argument.

If there is a rational explanation of the astonishing incoherence of this ‘solution’, it must begin with Heidegger’s conception of conscience. Conscience is the voice of ‘care’ which belongs to the very structure of a man’s Dasein (women apparently don’t count); it is the call that bids him to fulfil his own potentiality against, and in isolation from, ‘the everyday self’. Conscience is the wholly private voice, never the voice of communal experience, never the inward reminder of an external command, yet it is not ‘subjective’ either, because it is the voice of Dasein itself. True, in Heidegger’s Nietzsche lip-service is paid to the recognition that the single person ‘as such and always’ stands in a relationship to others, but that relationship (we are also told) is only accessible via a metaphysical understanding of Being, and is thus itself a metaphysical and not a social relationship. Mitdasein – togetherness – is identical with ‘forfeiture’ of the self ‘to the world’, and forfeiture ‘means absorption in togetherness in so far as togetherness is guided by chatter, idle curiosity and ambiguity’. As in Nietzsche so in Heidegger, the places where ‘two or three are gathered together’ are inauthenticity itself. What is at issue in Heidegger’s conception of conscience is not solipsism, which denies the independent existence of others, but the egoism that interprets considerateness – the consideration of others – as a betrayal of the self. But if this is what Heidegger believed when he wrote Being and Time, had he given up this belief six years later, when he joined the togetherness of the Party?

If there is a charitable explanation of Heidegger’s führer-like assumption of power, it must lie in his hope that by reforming the university he would bring about a community that was not guided by ‘chatter, idle curiosity and ambiguity’. The theme of his inaugural address is a threefold conception of service: in the Labour Corps (Arbeitsdienst), in the Armed Forces (Wehrdienst), and in the pursuit of knowledge (Wissensdienst). The mode in which he conveys this conception to his university audience is consistently military: the entire speech is cast in the lexis of danger, distress, force, breeding, exposure to dire necessity, heroic action consummated in a stand in the last ditch, and above all of Entschlossenheit, resoluteness in the face of the unfathomable and inexorable power of Fate. But this, too, is the lexis of National Socialism, or rather of one half of its propaganda (the other half is the promise of conquest, bounty and domination). If ‘our nation’ is ‘the metaphysical nation’, gripped in ‘the great double lock between Russia and America’ (the double lock of technology gone mad on one side, and social organisation ungrounded in Being on the other), then participation in the Volksgemeinschaft is justified by the Nation’s heroic fight for its ‘return to the question of Being’, from which the rest of Europe has defected. And, for good measure: ‘The Leader himself and alone is the present and future German reality and its law.’ Italicising the ‘ontic’ verb, Heidegger is making sure that there is no doubt about the metaphysical legitimation of the Führer’s – and thus also of his own – mission. And if, finally, guilt is involved in this participation, so be it: all Dasein is involved in guilt.

There is no moral or ethical motive behind this elevation of guilt to an inexorable mode of our existence but, like the Manichean fortiter peccari, it fulfils a redemptive purpose. In tracing this purpose, an interpretation in English is bound to run out of suitable terms, and will have to confine itself to paraphrase.

The momentous concept of Sein to which Heidegger appeals is all-encompassing, containing all ‘entities of being in the world’. At the same time Sein constitutes the radical ‘difference’ from all those worldly entities: a ‘difference’ which all explanations of Being by means of those entities seek to falsify and suppress – again, not contingently, but as constitutive of their very structure. The nihilism he speaks of is the suppression of this difference, and history is the chaotic process in which the uncovering (aletheia) and concealing, the ‘clearing in the wood’ and the mystery, truth and error (Irre) alternate – arbitrarily, unpredictably, one damn thing after another, each valid in and for its own brief moment, without any meaning, transcendent or otherwise. National Socialism, then, appears as one such moment, the age of planetary technology as the next and probably last. And the redemptive purpose? Up to the end of the Thirties and perhaps to the end of the Second World War, it is Entschlossenheit, the strong and passionate assent to this process. This ‘resoluteness’, however, is not a final, static purpose, but a valid way of being in the world – valid because through it a maximum of truth and falsehood is made to reveal itself. These analyses of guilt and history Heidegger never retracted. Only when the political solution failed did he offer the discovery of Gelassenheit (for example, in an address of that title in 1949) as a way of staying out of the nightmare of history.

This biography does not throw much light on the style of Heidegger’s philosophical discourse: his adaptations, adjustments and reversals of the meaning of common German words seem expressly designed to make paraphrase difficult and translation into another language all but impossible. Is the style then a sign of wilful obscurity? Or is it to be justified as some sort of poetry of concepts? The relentless fragmenting and etymologising of words must be ruinous to any conceivable notion of poetry. If the style is often inseparable from the philosophical substance, this is because Heidegger is convinced that the forms of the German language (and of Greek) do not merely describe and analyse Being, but are themselves re-enactments of it: the accidents of etymology are incidents in the history of Sein. This belief more than anything else is offered as proof of the relevance of his questioning, with the circularity of the argument acting merely as another confirmation of the fact that all our questioning and understanding of Dasein takes place within Sein and is encompassed by it.

A full consideration of Heidegger’s style would amount to a retracing of his philosophical vision, and of course there are points where the style can be adequately paraphrased. There its difficulties seem to be fashioned not by the grand ontological task but by a contempt for the language of ‘the everyday’, and the high-and-mighty diction merely conceals his kinship with the temper of his age. The writings of contemporaries such as Gottfried Benn, Ernst Jünger, Carl Schmitt (not to mention some of the ‘philosophers of the Movement’, licensed mountebanks with whom he was not ashamed to associate) mediate between the mysteries of the Sage of Todtnauberg and that part of the National Socialist ideology which emphasised the need for sacrifice, the ‘clear hardness’ of the struggle ahead, the value of intensity and ‘resoluteness’. There is nothing untimely about his political attitude, or about the concepts of conscience, history and guilt that explain it. Yet (and this is the paradox a reader of his work can hardly refuse to face) the monstrous timeliness of Heidegger’s philosophical vision does not diminish the importance or the originality of that vision. Of all those thousands of intellectuals who only did ‘what one does’, said ‘what one says’, and thought ‘what is thought’, he alone devised a category for their conformism. In this, too, he was representative of a society which, by pouring contempt on ‘the masses’, made them contemptible.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.