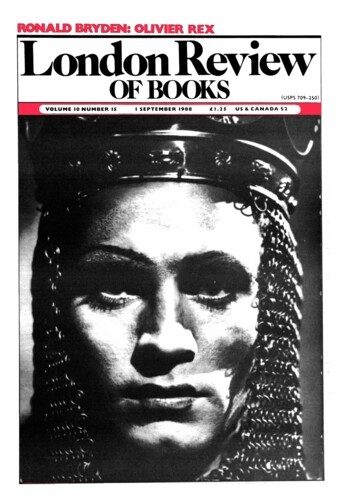

Anthony Holden’s is the 16th book about Laurence Olivier, and his foreword tells of two more biographers, John Cottrell and Garry O’Connor, too intent on their own deadlines to discuss their common quarry with him. All this activity may puzzle the lay person. Holden’s final pages report Olivier alive, as well as can be expected at 81, residing tranquilly in the Sussex countryside, still swimming occasional lengths of his pool in the altogether and attending the first nights of the three children who have followed Joan Plowright and himself into the theatre. Anyone likely to be interested in this book or its successors must remember that the actor published his own autobiography only six years ago, and a complementary professional memoir in 1986. In such situations, biographers usually hold their fire, waiting for time to unlock more secrets, death more tongues. Instead, Olivier’s are behaving as if a landslide of new evidence, too hot to hold there, had fallen into their laps. What is going on?

The occasion of the scramble is indeed a windfall of new evidence, but Mr Holden is too courtly (his previous subjects include Prince Charles and the Queen Mum) to name it. He merely says demurely that he persuaded Olivier’s friend, their shared publisher Lord Weidenfeld, that – how does he put it? – ‘between them [Olivier’s] two books did not add up to a comprehensive, let alone objective, account of one of the most extraordinary lives, in any profession, of this century.’ Holden has a nice line in dry understatement, and knows this is the understatement of the decade. What he means is that he and his fellow-toilers in the biographical olive grove have been racing to make sense of the great heap of myth, obfuscation, blarney and coded revelation dumped on them in Olivier’s Confessions of an Actor. Far from settling questions about himself, it raised them like flies. Perhaps it meant to. Had Olivier wished biographers to mushroom at his feet he could not have followed more closely the rules of mushroom cultivation: keep them in the dark and shovel manure on them.

The first question it raised was ‘What sort of man would write a book like that?’ The answer is: an actor. Olivier’s Confessions are neither confession nor chronicle, but a performance, designed to amuse, impress shock, wring and harrow. Reality figures in it, but only as actors evoke reality: by selection and amplification, blowing up details which in life would be too tiny for significance until the surface of everyday behaviour seems swollen with meaning. It is a technique which enabled Olivier, as so often on the stage, to hide in the spotlight. Promising a self-portrait, he painted across his own features a Kathakali mask of violent emotions, the grinning red, black and silver face of a tormented demon. This, his text declared with great cries of guilt, was the real Olivier: but what readers took in primarily was the enormous theatrical energy and gusto of the breast-beating. It was as if A. A. Milne’s Tigger, for some fancy-dress occasion, had tried to pass himself off as the doleful, droop-eared Eeyore, but been betrayed by his invincible bounciness. According to Holden, Olivier’s son Tarquin told friends privately when the book appeared that ‘it says absolutely nothing and gives everything away.’

This is the reason for the rush to print of Holden and his rivals. The race is to deconstruct and translate Olivier’s gestic text into terms accessible to those who deal in history, not drama – to reconcile it as far as possible with fact. Here Holden comes well-equipped. He has assembled all the facts available from previous biographies, as well as scores of entertaining new ones from his own researches and interviews with Olivier’s friends and co-workers. It is the largest compilation between covers of what is known about the actor, and that is its value, a real one. As a reconciliation with reality of Olivier’s mythic dance of himself, it is less successful. Holden never really gives the impression of seeing a subject’s view of himself as one of the facts a biographer must deal with. Rather, he treats it as something the biographer must get out of his way. It is as if Herbert Spencer or John Stuart Mill, not Mrs Gaskell, herself a novelist, had descended on Haworth parsonage to decipher the lives of the makers of Gondal.

Holden is too new to the world of theatre talk to have got all his details right, let alone arrange them into the figure in Olivier’s carpet. At the first dress rehearsal of The Merchant of Venice in 1970, he says, Olivier turned up with a hook nose and goatee modelled on George Arliss’s Disraeli and had to be persuaded by his director, Jonathan Miller, to evolve in the succeeding weeks a characterisation based on his own face. No one seems to have told Holden that dress rehearsals normally complete, not commence, the rehearsal process. He will surprise many who worked with Tyrone Guthrie by describing him as a ‘highly cerebral’ director, and amuse showbiz New York mightily with the statement that, after their star-crossed Romeo and Juliet on Broadway in 1940, Olivier and Vivien Leigh went to lick their wounds for a month in Vermont with ‘the Alexander Woollcotts’. The English period equivalent would be a month in the country with the Beverley Nicholses.

Holden is sometimes forgetful, evacuating the wartime Old Vic in one chapter to Burnley, in the next to Barnsley, and poor at sums. He gives the age of Olivier, born in 1907, as 39 when he achieved his triumph as Richard III in 1944. Tarquin Olivier, born in 1936, is credited with a visit at the age of seven to Notley Abbey, bought by his father in 1945. Nor has Holden checked all the stories he takes over from previous biographers. Like most of them, he tells how Olivier telephoned Ralph Richardson in the United States in August 1936 to ask if he should accept Guthrie’s offer of a Hamlet at the Vic. The transatlantic operator must have had difficulty connecting them: on 6 August, Richardson began a year’s run at the Haymarket in a thriller called The Amazing Dr Clitterhouse. Still, for such a bale of facts the level of error is not disgraceful. The most damaging result of Holden’s unfamiliarity with the territory he has strayed into is his acceptance of one of the theatre’s hoariest clichés: that the actor with a thousand faces has no personality of his own.

All actors suffer from our conviction that, having seen them on stage, we know them personally. I was once party to a discussion of the actor who provided the voice for Hal, the treacherous computer in Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001. ‘One can tell he has an enormous brain,’ one discutant said thoughtfully, ‘but do you feel he’s completely reliable?’ Similarly, Olivier has been plagued for forty years by half-memories of the first performance of his greatness: his Button Moulder in Guthrie’s production of Peer Gynt, which opened the historic Old Vic season of 1944-45. It is the Button Moulder who tells Peer to peel an onion if he would see the soul at its centre, and laughs when Peer discovers that onions have no centre. Ever since 1944, people have written that Olivier is a theatrical chameleon, taking on the colours of his roles, invisible offstage for lack of an identity of his own. Olivier has said it himself sometimes; it must save time in interviews. By definition, all actors are less vivid, less certain, offstage than on. Vividness and decision are what they rehearse all those weeks to achieve. But Olivier didn’t strike me as colourless the couple of times I met him off-duty. A boxer doesn’t have to hit people for you to know he packs a wallop. Being close to Olivier felt like being close to a champion boxer – acting had developed his chest and shoulders out of proportion to the rest of his body – and as unsafe.

‘Laurence Olivier is less gifted than Marlon Brando,’ wrote William Redfield in Letters from an Actor. ‘He is even less gifted than Richard Burton, Paul Scofield, Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud. But he is still the definitive actor of the 20th century. Why? Because he wanted to be.’ Holden’s book never reconciles his notion of Olivier the actor-as-onion with its pages of evidence that the force that through a hundred greenrooms drove his career was a huge, hungry, often ruthless will to succeed. Perhaps Holden has in mind Forster’s conceit in Howard’s End that the Napoleons of the world have will without personality; never say ‘I’ but only, like monstrous babies, ‘Want this,’ ‘Want that.’ Paying attention to Olivier’s myth of himself in his Confessions would have dealt with that assumption. Illogically, in allusions and images, Olivier enacts the dance of an Ego struggling to rise above the overmastering hunger of its Id. If his performance in the book has a through-line, it is the battle of his ‘I’ with his ‘want’.

Father Geoffrey Heald, the priest who introduced Olivier to acting at the choir school of All Saints Margaret Street, and played Petruchio to his 13-year-old Katharina in The Shrew, told him to read Dickens – as an actor, he would never want for characterisations. The early chapters of Olivier’s Confessions are written in Dickensian pastiche, even borrowing David Copperfield’s opening speculation whether he would turn out the hero of his own life story. The object of this is to characterise the young Olivier as a Dickens child, a version of David, and his father, the widowed Rev. Gerard, as his Mr Murdstone, the icy cheeseparer who darkens his world after his adored mother’s death when he was 12. You can smile at the cunning which colours his boyhood Dickensian, but photographs of Olivier in early roles at the Birmingham Rep bear his mythmaking out. The young face scowling from beneath beetling eyebrows and unwashed hair is clearly underfed, under-praised and underloved. No one has ever made much sense of the oracular morsel passed like a torch from Felix Barker, Olivier’s first biographer, to his successors: the story of how Elsie Fogerty, awarding the boy a scholarship to the Central School, ran her little finger from his hairline to the bridge of his nose, saying: ‘You have a weakness, here.’ Olivier, taking her literally, spent a lifetime re-building his nose with putty. Others have offered other, unkinder translations. The early pictures suggest she was simply warning him that he had developed a facial flinch: a shy habit of lowering his thick brows to veil the expression of his eyes. (Sixty years later, he is still doing it in Holden’s jacket photograph of his television Lear.) In most of them, you can make out the intensity he is trying to hide: an adolescent compound of suspicion, defiance, and seething resolve to show them all, be revenged, escape to some larger, splendid life where attention will have to be paid to him.

What image he had of that life is harder to read. Obviously the theatre was much of it. But none of his biographers looks closely enough at the role in his personal mythology of his Uncle Sydney, the first Lord Olivier, his family’s highest achievement until he overlook it. In his memory, Sydney is juxtaposed significantly to his father’s parsimonies: the bathwater his sons had to share, his razor-thin slices of chicken. When Sydney visited his younger brother’s rectory at Letchworth, Gerard ‘spent the few household pennies on vintage port and good food. Uncle Sydney was to have the best.’ Sydney Olivier was a founder, with Shaw and Sidney Webb, of the Fabian Society, and author of its essay on the moral basis of socialism. A star of the Colonial Office, he was twice governor of Jamaica and Secretary of State for India in the first Labour Government. Shaw called him one of the most powerfully attractive men he had known, ‘distinguished enough to be unclassable ... handsome and strongly sexed’, with the air, even in old clothes, of a Spanish grandee. It must have taken commanding qualities to get away with his career in the Colonial Service, one of open opposition to the enrichment of white colonists by an exploitation of black subjects. Rumbled finally and called home, he retired to a small, exquisite Elizabethan house in Oxfordshire to write a blazing exposé of the relations between white capital and black labour in southern Africa. In the few months he served Ramsay MacDonald at the India Office, he embarked on a plan for Indian independence, but was thwarted by Moslem intractability and the Government’s early fall. Olivier doesn’t make clear how much he understands of his uncle’s remarkable career as an antibody of empire, but evidently he took hungry note of the dignities that fall to those who have done the state some service, and of Sydney’s style. In On Acting he tells how he modelled partly on Sydney his 1970 Shylock, the one man of integrity in an oppressive Victorian setting of greed, luxury and speculation.

Rather than his roles colouring his life, his hunger and its objects coloured the roles in which, because they gave scope to the intensities he knitted his brows to veil, he was most successful. In Wuthering Heights, he gave his first satisfactory screen performance. Evidently the image of Heathcliff, the despised and outcast stable-boy who returns rich from America, connected with him as the swashbucklers and dapper young professionals of his previous films had not. In Henry V, first at the Vic, then on celluloid, he found an objective correlative for his yearning to serve England conspicuously and be conspicuously rewarded for it. But the role he seems to regard as mythically his own, the image of his life’s deepest truth, is Oedipus. The Sophoclean burden of the Confessions is that, of all men alive, Olivier has been the luckiest and unluckiest, the one who fell from highest fortune to lowest. In Oedipus he evidently found expression for his unstanchable sense that the sorrows of his life were punishments for a great guilt incurred ascending fortune’s wheel.

What guilt? Of all the empurpled, over-dramatised elements in his memoirs, Olivier’s harping on his sinful unworthiness reads most hammily. Yet he seems to have found the heart of his best performances – Richard III, Macbeth, Andronicus, Othello, Edgar in Strindberg’s Dance of Death – by drawing on this unexplained conviction of his own damnation. Clearly he believes it – believes that he owes his success to some Faustian deal with the devil, a debt he had to pay in torment. What debt? What Faustian contract? As Redfield implies, more than most actors Olivier gained his success by working for it, lifting more weights, breaking more bones, doing more voice exercises. What load on his conscience leads him to see himself as the 20th-century incarnation of Thebes’s incestuous king?

No Olivier biographer, and certainly not Olivier himself, has ever mentioned in print the principal reason why books about this actor are written and sold in quantities that will never be rivalled by works on Gielgud, Richardson or Alec Guinness. The nearest Holden comes is to retail a story by Gawn Grainger, the actor who helped Olivier edit On Acting from taped recollections, of watching the old man strip for his daily nude swim. Grainger could not keep his eyes from the tangle of operation scar tissue criss-crossing the septuagenarian torso. ‘Ah, yes!’ cried Olivier. ‘This is the body they used to worship. They all fell for me in my day.’ It seems necessary that somebody should say, for the benefit of the posterity which will know only that he was a great actor, what enabled him to become one: that his films put him in the small company of those – Byron, Nijinsky, Valentino, the last Prince of Wales – with power over the sexual imaginations of millions. Like an incubus, the Olivier of the Thirties and Forties could enter the dreams of the young, the reveries of the less young, and bring them to orgasm. Had he lived three centuries earlier, he might have risked being burned.

Exactly when he realised that he had this power, and what he thought of it, is hard to make out. His first encounters with New York fans after Wuthering Heights simply repelled and frightened him into refusing to sign autographs, as if they had invaded his privacy, not he theirs. His subsequent films, Rebecca, Pride and Prejudice and Lady Hamilton, show him muffling his sexuality in withdrawn diffidence, with that effect of coquetry which led some contemporaries to describe him as flirtatious. But knowledge of his power is clearly present in the scenes where he woos Katherine of France in Henry V and Lady Anne in the film of Richard III. (It may even be there in his night scenes with his army before Agincourt.) The strongest, because most casual, evidence I saw him give of knowing it was in The Master Builder at the National Theatre in 1964. As Joan Plowright’s Hilda told how Solness had possessed her dreams, seduced her in imagination, he nodded intently as he listened. She was telling him nothing new, merely confirming something he knew he was capable of. None of his contemporaries could have played that reaction as he did, so matter-of-factly. But of course the same knowledge was there, only half-hidden by disgust, in his playing of Archie Rice in The Entertainer. You can’t leave me behind here in this theatre, Archie’s gat-toothed leer told us. I’ll follow you home into your sleep, and you won’t like what happens when I get there.

Obviously part of his nature – the rectory child who swung the censer at All Saints – felt his power as a sin and curse. A maturer part may have felt, with more real guilt, that it was a fraud and imposture. Denys Blakelock, one of his earliest friends in the profession, told in his memoirs how Olivier won his mother’s heart by his evident unfitness for a stage career. ‘He’s such an ugly boy,’ she said pityingly, and Blakelock could not deny it. The 20-year-old Olivier’s hairline was simianly low, his eyebrows tangled over his nose, his front teeth had a gap wide enough to stick a straw in, and his starved frame looked even bonier in suits handed down by his uncles. By the time he left the Birmingham Rep for London, he had transformed himself. Photographs of the early Thirties show a glossy young matinee idol with plucked eyebrows, romantic cheekbones, flawless smile and enough oil on his hair to service a Morris Minor. ‘Valentino taught me the importance of narcissism,’ he told Ken Tynan in a BBC interview in 1967. (He evidently studied film actors: his trick of rolling dead eyes upward till the whites showed came from Fritz Kortner.) He worked hard on himself, and the work paid off in matinee idol parts: Beau Geste, Bothwell in a thing about Mary Stuart, the John Barrymore caricature in Edna Ferber’s and George Kaufman’s Theatre Royal. It was in the last that he was first seen, and marked down for her own, by Vivien Leigh.

There, it seems, lies the root of his guilt, the buried crime he thinks he spent his life expiating. By imposture, turning an unlovable self into a brilliantined dish for Hollywood’s sex scouts, he attracted the love of the world’s most beautiful woman and the wrath of the gods. Their life together, in his myth, is his punishment, their marriage the infernal machine, as Cocteau put it in his version of the Oedipus story, designed by fate to destroy a man. A stagy notion? The stage is his language, and what he is saying rings true enough. As he told the world in painful detail in the Confessions, he could not convince offstage in the role of a great lover. He must have felt seen through in other ways. Vivien Leigh had more schooling than he, and more to show for it: wit, taste, social grace, quickness with languages. She read books. He seldom mentions reading anything but plays and newspapers. The one thing he had of his own which she could not match was his talent. To undo his fraud and become a real hero for her, he made himself a great actor.

That was what drove them apart. On the most basic level, he tells in his memoirs, acting as he acted drained his sexual energies. Acting as she acted did not deplete hers. She read his belief that she could not love him unless he surpassed Kean and Irving as a message that he could not love her unless she excelled Rachel and Duse. Her knowledge that she could not – that she would never equal him professionally – fuelled the manic depression which, from 1945 on, led her downward into schizophrenia. (That was the year he played Oedipus.) The forms her madness increasingly took were raging abuse of him and compulsive infidelity with younger men picked up after the theatre – the role that became her personal myth was Blanche Dubois in A Streetcar Named Desire. Holden points out, with some justice, that in fact it was she who was destroyed, while Olivier survives. He takes this as testimony that her love was the greater; that his egotism armoured him against the slings and arrows of the life of emotions. I find that glib. What destroyed her was her disease. It is impertinent of anyone who has not done so to judge the actions of someone compelled to live intimately with a manic depressive. This is where more time needs to pass, more evidence become available. Vivien Leigh’s friends are free to tell her story. Olivier’s have had to leave his to him.

What Vivien Leigh destroyed in Olivier was his belief in himself as hero of the British Empire. From 1945 onward, the two of them were part of the national life as no actors had ever been before: received by royalty, friends of Churchill, treated in public almost as if royal themselves. It seemed natural that Olivier should speak the commentary for the film of the Queen’s coronation in 1953. He had become an element of what Bagehot called the ceremonial aspect of the British constitution: the Performer Royal, slightly junior to the Poet Laureate, but of more use on state occasions than the Astronomer Royal, who can’t even cast horoscopes. When he and Vivien Leigh led an Old Vic tour to Australia in 1948, their progress was viceregal: banquets from premiers, speeches of greeting from the British nation to the Australian people, everything but launching ships. Touring of this kind had been invented by Henry Irving and his advance men, but never brought to such stateliness. Olivier started a diary which reflects the glory he took in it all. He had outstripped not only his predecessor as head of the profession, but also his Uncle Sydney. In Melbourne the diary breaks off. The reason Olivier gave was strain, a usefully ambiguous word. It covered both real exhaustion and the state of his marriage. It was in Australia, he maintained afterwards, that he lost his wife’s love. She had taken to flirting publicly with young actors in the company. In private, they quarrelled emptily. Their next stop was Sydney, where Vivien Leigh would meet the man who demolished what remained of the great love, Peter Finch, and Olivier received the notorious letter from the chairman of the Vic’s board of governors informing him that his services, and Ralph Richardson’s, would not be required next season. The life of the Performer Royal had become a performance. It was after this that Olivier began agreeing with interviewers that, yes, an actor is a hollow man, with no life to speak of offstage.

It was early in the Fifties, too, that people started to tell stories about not recognising him in street clothes. He let the matinee idol beauty fade as swiftly as he had created it. It’s interesting to study his make-up for his later roles. For heroes – Hamlet, Henry V, Coriolanus. Oedipus, Antony – he had always painted a fuller, more sensual upper lip over the thin one he inherited from his father. Part of a hero’s being, he evidently felt, was physical seductiveness, sexual power. His 1955 Macbeth was the last role for which he did this, if you exclude his African Othello. From 1950 on, he specialised in playing heroes as character roles, to observe rather than fall in love with: heroes with something wrong with them, flaws, secret vices or burned-out cores. His guide to Shakespeare, characteristically, had always been A.C. Bradley’s Edwardian analysis of the divided moral natures which destroy Hamlet, Macbeth, Antony and Lear. His forte as an actor became the illustration of such destruction: heroic magnificence riven and eaten from within.

It’s hard to resist the conclusion that the unique national eminence he reached in the last third of his career resulted from the resonance between his great performances as flawed, dishonoured proconsuls and the British public’s mixed feelings about the end of empire. During the war, as Nelson and Henry V, he had established a special relationship with his public by offering simple icons of British courage and decency winning the day. Now, as the Empire had to be let go, he provided images of the necessity for its surrender: instances of imperial virtue corrupted by passion or power – Antony, Macbeth, Coriolanus again, Othello and, perhaps most memorable of all, Titus Andronicus, the old hero who, meeting the onset of barbarism with cruelty to match its own, hastens the twilight of his civilisation. Rich and complex, his performances gave British audiences the wide palette of emotions they needed to deal with the change to their world: shame and splendour, nobility and waste, loss and deliverance. His creations were of the scale the fall of empire demanded; better than Ian Smith or Enoch Powell. But among them also belongs his Archie Rice in The Entertainer, imperialist turned malcontent, lamenting the Empire’s passing while railing at the dishonour it descended to at Suez. When he said, ‘Don’t clap too hard, ladies and gentlemen, it’s a very old building,’ our scalps went cold. The intensity of his vision of a rotting kingdom pierced through the theatre walls out into the darkness of imperial London, eating the faces of statues and the facades of Whitehall, until we looked in imagination over the moonscape of the city after the raids.

It couldn’t have worked had anyone at the time been very clear about what exactly his performances were doing for his audiences. Kenneth Tynan proved that when, in an excess of lucidity, he enmeshed Olivier in his efforts to acquire for the National Hochhuth’s play Soldiers, with its portrait of Churchill as hero, machiavel and murderer. In spite of its ludicrous length and prosy naivety, the play tuged at the same roots, with some of the same power, as Andronieus and The Entertainer. The hope was that Richard Burton, the actor most like Olivier’s heir, might play the Churchill role, and Tynan obviously expected Olivier to direct. It was a lunatic notion. Tynan must have known perfectly well that Lord Chandos, chairman of the National’s board, had been Churchill’s colleague in the war cabinet and so, if Hochhuth were dealing at all in fact, an accomplice in the crimes imputed to his chief. The interesting thing is the way Olivier floundered, confused, in the midst of the imbroglio. Clearly the play struck certain chords in him. Clearly he saw the reddened face of Chandos shouting at him that Tynan must go as the unacceptable face of the old empire’s power. What he could not tell was whether the play itself was bad or good, or what he should do in the circumstances. He paltered, and in the end damaged his standing with the board irretrievably. His prestige in the country at large made him impossible to fire, but after the Soldiers affair a faction on the National’s board obviously counted the days until he could be retired gracefully.

Did he himself recognise clearly his role as an imperial antibody, after the fashion of his Uncle Sydney? I doubt it. At some lesser crisis in the National’s fortunes, his press officer asked if I would mind lunching with ‘Sir’ so that he could let Fleet Street know how sharper than a serpent’s tooth it is to have a thankless press. (And indeed, he played a pocket version of Lear in modern dress just for me; but that is another story.) One of the issues on his mind was whether his company was entitled to call itself the National Theatre of Great Britain. People had said it should bill itself abroad as the British National Theatre, the ‘Great’ might cause offence. I started to make the harmless geographical distinction between Bretagne and Grand Bretagne, but he brushed it aside, too obsessed to listen. When he was at school, the map had been covered in pink, and Britain was great, dammit, and people were proud of it. He couldn’t understand this new feeling in the country against greatness, could I explain it?

I didn’t try, and hope no one else ever has. If anyone could have persuaded him that the word ‘great’ has no objective meaning, but is simply a counter of patriarchal discourse designed to shore up the power of élites by ‘valorising’ their leaders and favoured aristocratic forms of art, he couldn’t have been what he was. That is why it is important to listen to his myth of himself. He was a great actor because his acting was about greatness, both its dark and its golden faces. I wouldn’t have forgone seeing it for the chance of a total reform of the Indo-European family of languages.

I hope the English will go on playing the role of Chorus his myth allots them. Evidently he took the trouble to find out what happens to Oedipus in the long run, in Oedipus at Colonus. By knowing greater suffering than any man alive, enacting it publicly for the purgation of his city, the outcast king finally achieves an unearthly peace, his sins forgiven his white hairs by the gods, in the company of his children. Indeed, the unique greatness of his ordeal invests him with mana, makes him a living treasure whose resting-place Thebes and Athens dispute, knowing that the land where his bones lie in honour will harbour a great fortune. Because he no longer had the force to convey its torments, it seemed to me, it was the old, redeemed Oedipus he chiefly played at the end of his television Lear. I hope his Chorus will know their lines when their cue comes.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.