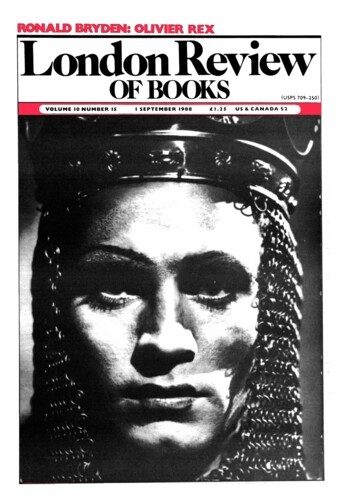

Olivier Rex

Ronald Bryden, 1 September 1988

Anthony Holden’s is the 16th book about Laurence Olivier, and his foreword tells of two more biographers, John Cottrell and Garry O’Connor, too intent on their own deadlines to discuss their common quarry with him. All this activity may puzzle the lay person. Holden’s final pages report Olivier alive, as well as can be expected at 81, residing tranquilly in the Sussex countryside, still swimming occasional lengths of his pool in the altogether and attending the first nights of the three children who have followed Joan Plowright and himself into the theatre. Anyone likely to be interested in this book or its successors must remember that the actor published his own autobiography only six years ago, and a complementary professional memoir in 1986. In such situations, biographers usually hold their fire, waiting for time to unlock more secrets, death more tongues. Instead, Olivier’s are behaving as if a landslide of new evidence, too hot to hold there, had fallen into their laps. What is going on?