A very disturbing thing has happened to journalism, to the writing of history, and even to justice. In anything to do with the Nazis, whose doings continue to preoccupy us 45 years on, any attempt at detachment is considered suspect, any degree of objectivity reprehensible. Somewhat obsessed with the subject myself, I have a good deal of personal experience of this phenomenon. Over the past twenty years I have spent some thousands of days, I suppose, talking to one-time Nazis, to those who suffered under them and those who fought them. I have written about the unpopular Nazi-crime trials in Germany – and was criticised for praising the Germans for their tenacity in going on with them. I have written about the so-called ‘revisionists’, who obscenely wish to deny the existence of the gas-chambers – and was criticised for upholding their right to voice these irrational opinions. I have battled in print against people like David Irving (Hitler’s War), who misuse history to advance their dangerous ideologies, and, at the other end of the scale, men like Martin Gray (For those I loved), who use these appalling events for self-aggrandisement. Interestingly, nobody minds much about Irving, but attacking Gray causes wrathful indignation among Holocaust dogmatists. I sought to learn from men who became monsters, such as Franz Stangl, Kommandant of Treblinka (about whom I wrote in Into That Darkness) and was severely taken to task by the same kind of fanatics, who feel that it is not only pointless but immoral to engage in dialogue with such men.

The Hitler Diaries scandal ended in a disgraceful trial and prison sentences for the little forger-crook Kujau and the Hitler-bedazzled Stern journalist Heidemann. Eight months’ research into the background proved to me that there were very different political forces and psychological motivations behind this deplorable episode from what had been assumed: but the idea was generally unacceptable. The two dupes had had their just deserts; the public – in Germany and America most of all – got the laundered story it appeared to want; and the people who had really conceived this disgusting whitewash of Hitler are sleeping soundly in their beds.

And then in 1987 we had Klaus Barbie. Let me hasten to add – before I am accused of carrying a flag for criminals – that there is no doubt that Barbie, a carefully-trained Gestapo officer with a real penchant for torture, was a particularly unpleasant specimen whom many people have reason to remember with horror, and who – like many others – should not die peacefully in bed. But the roll-call of horror is long and infinitely varied, and nothing that has emerged about Barbie (except that his field of wartime activity was France) can explain the inflated media reaction or the judicial handling of his case.

Thus the much-praised Lyon court appeared untroubled by the disappearance of the principal witness for the defence, whose hiding-place in Alsace was found with ease by journalists, but who remained ‘introuvable’ by the French Police. Is it conceivable that this was because the witness might have disproved the involvement of Barbie in the most heinous crime of which he was accused, the only one that clearly came under the heading of a ‘crime against humanity’, which, since ‘war crimes’ were barred under the statute of limitations, was the only one he could still be tried for? This was the deportation to Auschwitz of the Jewish orphans of Lisieux. Quite apart from the missing witness, whose evidence could have been that Barbie was not present when they were rounded up by the Gestapo, the court also blithely ignored unequivocal documentary proof (of which I have a photocopy in my files) that it was not Barbie but a group of Eichmann’s henchmen in Paris who made the decision to send the children to Auschwitz, where they were killed.

The final mockery of justice in the Barbie case was the delivery of the judgment – on an indictment of over three hundred points – precisely on the schedule announced five days before: grotesquely, less than five hours after jury and judge had retired.

It is true that the perception that not only the Nazis but every violent society produces men such as Barbie (see Algeria, Vietnam, Cambodia, the West Bank and finally Ireland) is gaining ground. Barbie’s counsel, Maître Jacques Vergès, based his whole defence on the premise that a French court was not qualified to sit in judgment on a German who had done the same in France as the French, unhampered by public or judicial censure, had done in Algeria (where his wife underwent torture). Monsieur Vergès considered the Barbie case so unwinnable in Lyon that he made the deliberate decision to use it for polemical purposes (however honourable). While it is certainly true that the principle of holding men individually responsible for crimes against humanity in war or ‘on the back of war’ has to be applied equally to all men and all nations, this in itself does not disqualify any particular court from trying such men, and it most certainly does not exempt Nazi criminals from being tried wherever a court represents those against whom they offended. The problem of such trials, however – aside from the logistical one of the age, health and memory of the accused and witnesses – is the atmosphere in which they take place. The real significance of the Barbie case was that the court allowed itself to become involved in trying a symbol. The significance of the Demjanjuk case in Israel is that there the judges have attempted, despite immense handicaps, to try an individual.

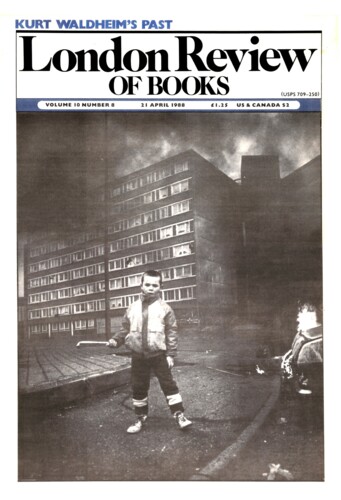

As matters stand at present, those called to account – by the media rather than by the courts – for their actions under the Nazis fare very differently from soldiers who can plead provocations we can sympathise with, or men from civilisations other than ours. By unspoken accord, objective assessment is withheld from anyone who did anything, or left anything undone, under the Nazis. There is at present no one to whom this applies more than the President of Austria, Kurt Waldheim, to whose alleged deeds and moral flaws the world press has devoted millions of emotive words over the last two years. What is it about this essentially rather simple man that arouses such violent passions?

‘Why do they go on so about me? Do you understand the reasons?’ he asked me, sounding honestly puzzled rather than self-pitying, when, during the week leading up to the Anschluss commemorations in Vienna, I spent several hours with him in the Hofburg, where the Emperor Joseph II’s huge golden office is now his. Our meeting had been planned as an informal talk on questions of faith and morality, rather than one more inquisition, of which he had by this time undergone dozens.

His face alight, he lovingly explained a magnificent painting in the corner where we sat down to tea, of an amateur operatic performance at the Palace of Schönbrunn in 1765, to mark the Crown Prince Joseph’s marriage to Maria Josepha of Bavaria. On stage were the four daughters of the Empress Maria Theresia; in the audience the huge Imperial family and their suite. And had I been shown the little altar built into a bit of movable wall next door, in what had been the Empress’s bedroom?

‘Even the British Queen thought our Hofburg extraordinary,’ said his personal assistant, 37-year-old Ralph Scheide, who sat in on our conversation.

‘He knows more about me than I do,’ Waldheim joked. Scheide, who took on this difficult job six months after Waldheim had been elected, addresses him as ‘Du – Herr Bundes-präsident’.

The lack of antipathy Waldheim aroused in me is echoed in the above books, which belong to the two ends of a spectrum. Waldheim, by two French journalists, Luc Rosenzweig and Bernard Cohen, is more of a tract than a historical examination, whereas Waldheim: The Missing Years is by an American historian. Herzstein was the first researcher to be commissioned, by the World Jewish Congress, to look into Waldheim’s past, and the Austrian President – who finds it difficult to hide his feelings about that body, though he tries – will be hard put to believe that anyone so selected could think or write anything positive about him. Nevertheless, only Herzstein’s prologue – in which he dramatically recounts hearing of the discovery of an ‘old faded document on microfilm’ in which the Yugoslavs charged Waldheim with murder as a war criminal – panders to public expectation. The remainder of the book, barring a few forgivable speculations, is a very meticulous and even sympathetic analysis of claims and counter-claims.

The French offering runs true to form. The track record of French publishers for fast production of a hot story is particularly good. But Gallimard’s publication of Waldheim as early as 1986 meant that – even if the authors had been so inclined – there was little scope for real research. Basically, then, with condemnation of the luckless Waldheim for every Nazi crime under the sun lurking on every page, this book is a collection of anecdotes, culled from largely unnamed sources and padded with facile interpretations of unreliable data, and innuendos where there are no facts. A quick look at a few of the playful chapter headings will convey the approach. ‘The Germanisation of the Vaclaviks’ is supposed to demonstrate the self-serving character of the Waldheim family, whose Czech name Watzlawik was changed by Waldheim’s father after World War One, no doubt in the same pragmatic spirit in which millions of Americans of European ancestry Anglicise their names. The catchy subtitle ‘A Brownshirt in 1938’ of course implies that Waldheim was a Brown-shirt – an unproven allegation.

Much worse than these flippancies, though, is the downright tendentious chapter heading, ‘In Salonika during the Deportations’: collaboration in the deportation of the 50,000 Jews of Salonika – in the knowledge of what was to happen to them – is probably the most serious accusation against Waldheim. The precise dates of his postings have been available for some time. He was on study leave in Austria from 19 November 1942 to 31 March 1943; in Tirana from 1 April to early July; after a few days in transit at Arsakli, near Salonika, he was in Athens from 19 July to 4 October. The ghettoisation and sub-sequent deportation of Salonika’s Jews took place between February and May 1943, with one last train in August. What Waldheim knew or didn’t know is impossible to prove, but he wasn’t there.

The French journalists did hit upon one interesting story that I had not seen published outside Austria before, which has to do with how the whole saga really started.

In the run-up to the Presidential elections in Austria in 1985, the historian Georg Tidl, a Socialist, stumbled upon information in Balkan war archives to the effect that during the war Lieutenant Kurt Waldheim – who was being mentioned as a possible candidate for the conservative People’s Party – had been on the staff of Army Group E in Greece, commanded by General Alexander Löhr, himself executed by the Yugoslavs for war crimes in 1947.

Personal smear campaigns are not in the tradition of Austrian politics. Also, the Socialists knew perfectly well that stirring the pot of Austria’s murky Nazi past was unlikely to attract the voters’ sympathy. The decision was nonetheless made to plant rumours about Waldheim’s past abroad. If the rumours came from outside, they reasoned, they couldn’t be laid at their door. One bad decision was quickly followed by another: they chose a nice man named Leon Zelman as their messenger, and sent him off to America with the news that the People’s Party was about to propose for the Presidency of Austria someone with a possibly unsavoury wartime past which he was trying to hide.

Leon Zelman, a Polish Jew by birth, had come to Vienna from Auschwitz via Maut-hausen in 1945, when he was still a boy. Some kind people – socialists, as it happened – provided him with a home, a country and ideals. He developed into a warm, idealistic man, dedicated to repaying the kindness shown to him in Vienna by rehabilitating his adopted city in the eyes of foreign Jews.

It was to one of the friends he had made in New York during his years of bridge-building – Israel Singer of the World Jewish Congress – that he brought the information about Waldheim. For Singer, who had little knowledge or experience of diplomacy, passion overrode all rational considerations and exposing Waldheim became a ‘cause’. The disastrous result was that the accusations against Waldheim came from America and from Jews, with the predictable consequence of an election with appalling anti-semitic overtones, and a profoundly disturbing rise in anti-semitism not only in Austria but in Germany too, where it had for so long been taboo.

It is perfectly true – as Herzstein and others have suggested – that the one person who could have affected and altered this attitude was Waldheim himself. But for this he would have had to be either very well advised – which he wasn’t – or a different man, the great statesman he longs to be.

‘You ask me whether I feel bitter,’ Waldheim said to me a few weeks ago in Vienna. ‘I do feel bitter about what it is doing to my family. Can you imagine our lives?’

I said that surely he wouldn’t claim not to feel bitter about some individual Jews? He wasn’t, after all, a saint – ‘St Kurt’. I was trying to lighten the atmosphere, and he gave a brief smile. But he didn’t answer this, directly.

‘I have a particularly good Jewish friend here to whom I talk a lot,’ he said. ‘He keeps saying that he is terribly afraid of the effect all this is having on Christian-Jewish understanding, the reactions perhaps yet to come against Jews. I am very concerned about this, for Austria. I am very aware of the suffering of the Jews ...’ The sentence petered out.

‘You see,’ he started anew, ‘in order to destroy me, personally and politically, Austria is attacked – this is what most concerns me now. The international community does need to remember that it was the Allies in 1943 who decided that Austria was a “victim” – one surely cannot blame the Austrians for accepting that interpretation in 1945. In 1934 there was civil war in Austria and no possibility of co-operation between parties. Then, out of the concentration camps, from those Austrians of all parties who were imprisoned there together, came the determination to create a “beyond-party” collaboration and this is what was done.’ The result, he said, had been an unprecedented period of political harmony. ‘Forty years during which Austria has made herself the stabilising centre of Europe: that is what is now at risk.’

Leaving aside for a moment what he knew or didn’t know, said or didn’t say, I asked whether he felt – as, in fact, I do – that his predicament was at least in part the result of a generation gap? That a great many people now simply cannot envisage life under the Nazis?

I could almost hear his sigh of relief. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘You see, what happens is that people consider what happened then in terms of Western democracies now. While in fact, with just one word out of turn then, one risked not just prison but execution. I remember once coming upon my father, his ear pressed to the radio, listening to the BBC. And – I can see him still – I saw him start in stark terror as he heard my steps. How can the young today understand that kind of atmosphere? I love talking to the students who come here, although, yes, they do ask difficult questions. But that is only right. One boy asked me recently why I didn’t just take off my uniform, throw away my weapons. He is right, it’s a fundamental question. Of course, I could have. Perhaps I should have ...’

What is a hero? I asked: the historians’ commission – which the Austrians set up and paid for – seemed to think that is what he should have been. ‘Yes,’ he answered. ‘That is a real question. I thought that the commission, who after all I asked for, would understand. Would I really have asked for such learned men to investigate my past if I had done something wrong? Those who think me bad, do they also think me mad? But it is true, of course. I could have resisted, deserted, and I didn’t.’

That was what he said now, but did he ever actually consider such a choice?

‘One did think about it, of course, but ...’ He paused. ‘You see, my father and my brother were both active anti-Nazis – my father lost teaching job, was imprisoned, beaten up ... I think,’ he said slowly, ‘it was because my family was so endangered that I felt ... army life was ... safer ... than being a civilian. It is true. I wanted to survive.’

Did he know any Jews?

‘Oh yes. I’m in touch now with three of my Jewish school friends, one in America, one here, and then of course Lord Weidenfeld – my old friend Georg – he was kind enough to give me an affidavit.’ If that was a sad term for a head of state to use, he didn’t notice.

Had he known about Hitler’s feelings about Jews? Had he read Mein Kampf? He smiled – it is extraordinary in Germany and Austria, how people always smile when asked this question. That old condescension toward ‘Corporal Hitler, the house-painter’ still survives. ‘Perhaps I should have read it,’ he said then. ‘I might have understood more: people say that everything was in there. One thing, though: you know the Americans’ – he means the American Jews but cant or won’t say that – ‘are always talking about the “Nazi Wehrmacht”, but the staff of the Wehrmacht really was not Nazi – one was very carefully vetted before being taken on. In a way, you know, my problem was that I was never directly confronted with horrors: our home was in a small town, the Jews there were people one knew. I certainly never saw anyone being mistreated there in 1938. When I fought in Russia-riding with my troop of 70 cavalrymen in front of the infantry drawing the first volleys, so to speak – I never saw a Partisan. And then on the staff it was all reports, and I can assure you no troop commander reported: “Today we committed horrors.” Perhaps within the SS they did – I never knew any.’

Was he saying that the reports he saw did not mention Partisans?

‘No, of course they’d report “encounters with Banden” and Säuberungen – clearing-out. But these were actions of war – Partisan warfare was very hard, on both sides.’

But then what about Sühnemassnahmen reprisals – against whole villages, women and children? Did that not appear on reports? Did he and the other young officers never talk about any of the blood-baths in the midst of which they lived?

‘It wasn’t like that.’ He sounded desperate. ‘In Greece I sat in a little former American college overlooking the vineyards and the Aegean.’

But in Yugoslavia? Wasn’t he in villages there which were less than twenty kilometres from the terrible Ustasha camp of Jasenovac, where countless thousands died?

‘Was it really so nearby?’ he asked – I thought disingenuously. ‘But anyway, those were Ustasha installations ... The only thing ever brought against me was a forged telegram. The commission have looked for proof against me for six months, have read thousands of documents: nothing has been found. All they could say was: “He must have; he should have; he could have; he might have.” And in spite of this, for eighteen months now one can’t open a paper or turn on the radio without reading, hearing these awful things they say about me, in their appalling language. Can you imagine what this is doing to my family? My 11-year-old grandson who comes home and asks: “Is it true that grandfather is a war criminal?” Good God, knowledge, after all, is not guilt.’

But wasn’t what he had been saying precisely that he knew nothing? ‘I never saw anything.’ But he guessed, and thought? ‘You mean, I’m not made of wood: I’m glad you feel that. And of course one thought. But in law there is a big difference between knowing and doing ... If a report mentioned “reprisals” a few hundred kilometres away, what could one have done? Nothing. Even the commission said that even if I had given my life, it wouldn’t have helped.’

But is there no moral responsibility apart from practicality? I asked. In that case, where does guilt lie?

‘Not in mere knowledge,’ he said. ‘Only in not doing anything, if one was in a position to do something. I am religious – I pray. I often prayed that these horrors of war should stop.’

Didn’t he feel that it was facile – not worthy of him – to just do away with the horrors by justifying them with war?

‘It is good of you to say it like this. I’m prepared to go further ... Please ask.’

‘You say you prayed,’ I said. ‘Did you ever go down on your knees – with the image of terrible things which happened in your mind’s eye – and pray: “Please God, please stop this.” ’

‘Not in that form: I prayed – as I told you – that all the horrors of the war should stop ...’

Did he not see that in a sense he was – or is now – using the war?

‘But it was war,’ he said despairingly. ‘Greece, Yugoslavia, Russia – savage war. But Pearl Harbor too – Hiroshima – and later, what about Vietnam, and now the West Bank, where they are breaking people’s bones? In all these places the innocent died and die, women and children by the hundreds of thousands: who spoke for them, who protested there?’

I suggested that it was indeed protests in America, largely from the young – civic action by civic-minded human beings – which stopped the war in Vietnam, and I could have added, but didn’t, that the Israelis are calling their soldiers to account for their conduct on the West Bank. But he did not – does not – hear this kind of argument. One gets the feeling that he can no longer (if he ever did) hear things which don’t refer to his situation, and don’t apply to or agree with the way he links it to other matters.

‘How about horrors then which had nothing whatever to do with war?’ I said. ‘Can you apply the same standard to Pearl Harbor, for instance, and Treblinka? What about Treblinka?’ I asked.

‘Treblinka,’ he said heavily, ‘is something entirely different. You are right: it had nothing to do with war. It was a political act. It was an abomination. It was a crime. But you see, I knew nothing about these terrible places until after the war: how could a normal person imagine that anything like this could be done? Of course one knew about camps – concentration camps, where they sent many non-Jews too. Of course one realised that Jews were disappearing in Austria: one thought they were interned. Wiesenthal, who I helped look for Mengele when I was Secretary-General of the United Nations, has been very kind to me over these last two years. He said not long ago: why didn’t I just admit that I knew about the deportation of the Jews of Salonika, which my enemies say I “must have” known about. Why not just say I did – it would make it all so much easier? But I can’t say that, because I didn’t: I saw nothing. But I would have to add that even if I had “seen” something, I wouldn’t have known – and had I heard rumours (which I didn’t) wouldn’t have believed – what was being done. I have to say too: what did the Americans do, or the British – who, as it turns out, knew more than we did? But we are back with what you said at the beginning: the inability of people now to envisage life under the Nazis. I’m being accused of “knowledge” because, in terms of the dissemination of knowledge, the level of public knowledge, today, they think one “must have known”. But the fact is, one didn’t. And I don’t admit the thesis of “collective guilt”.’

Wasn’t guilt, I asked, the expression or admission of it, an inner necessity? In a way, was it not part of ‘sin’ in a Christian – particularly a Catholic – sense? I, for example, felt in a way guilty too – not for anything I had done but for what, perhaps because of my own deficiencies or simply because of circumstances, I had left undone. Was ‘collective guilt’ not acceptable or applicable in that context, in which – compared to those who suffered so gravely – we did not suffer enough?

‘You feel that this sin of omission, by all of us in Austria and Germany,’ said Scheide, interested in this approach, ‘is really inherent in the human being – part of “original sin”: is that what you mean?’

‘You say you didn’t suffer enough,’ said Waldheim – he really is a pragmatist, feels at sea with abstract thought, and, compulsively and repetitively, brings all conversation back to his accusers and himself. ‘I think we did. When, after the war, one learned about these abominations, of course one was appalled at what had been done and horrified about the iniquity, the extent of human depravity, that had made it possible. But during the war I never knew a single person who might have known about it.’

Dr Scheide said that so much that has been written is a matter of interpretation, and this applied particularly to what some of the media has made of Waldheim’s role – or absence of it – in the interrogations of British Commandos. I said that I myself felt uncomfortable about the attacks against the President on that score: it seemed somehow preposterous to me to condemn retroactively any young intelligence officer in the German Army for not being sufficiently a hero to act against orders pertaining to Commandos. Waldheim said he had enormous admiration for anyone who did so act, but thought it would have been possible only in comparative isolation and with the clear support of a superior, as was the case for the admirable staff captain Günter Kleykamp of General Felmy’s 58th Army Corps in Athens, who with the knowledge of his general reported his interrogation of two British officers to the Swiss Red Cross. As a result, Captain Robert MacGregor and Lt Capsis were accorded POW status, escaping the Sonderbehandlung – execution – of Commandos which was ordered by Hitler in October 1942.

‘Of course I knew about British Commandos,’ said Waldheim, ‘only I myself never interrogated any. But you can see what happened when I said that some time ago: immediately the interpretation was that I had “admitted” something, “admission” being automatically associated with “guilt”. In fact, all I did was to confirm that I was privy to information regarding Commando operations. After all, that was my job, to be informed – and to pass on information to my superiors – about operations. And yes, of course I knew about the Führerbefehl – possibly not at that exact moment, but I certainly remember hearing about it at some point or other: everyone on the staff did. Personally, however, thank God, I had nothing to do with implementing it.’

The exhaustive research which Herzstein – and later the historical commission – undertook to ascertain the precise degree of Waldheim’s involvement in the interrogation of British and American Commandos, and his responsibility for the subsequent Sonderbehandlung of so many among them, has netted the predictable results: Waldheim’s intelligence unit was involved in interrogations, though as far as could be found torture and executions were reserved for the SD (SS Security Service), to whom prisoners were sent after ‘ordinary’ interrogations by the Wehrmacht within the rules of the Geneva Conventions were completed.

Waldheim’s initial has been found on one interrogation report only: that of James Doughty, an American medic, who as a non-combatant survived the war as a POW. Aside from this, the only documents pertaining to ‘Anglo-American (Commando) missions’ bearing Waldheim’s signature are the daily operational reports for which he was responsible. It can be – and is being – argued that anyone who knew of Hitler’s order to kill all Commandos and took no individual action against it could be considered an accomplice in what the Nuremberg Tribunal would call ‘war crimes’. But this is precisely the kind of mindless retroactive generalisation that is leading to hysteria. And it avoids essential, if uncomfortable questions. One – answered affirmatively by the commanding officer of one of the Commando operations – is: were these Commandos not aware that if they were caught, they were as ‘expendable’ as were the Germans they had come to attack? Neither Commandos nor Partisans could take prisoners. And the other uncomfortable question is: what is someone like Waldheim supposed to ‘admit’?

There is a profoundly significant difference, it seems to me – and, as we can see from his book, to Professor Herzstein too – between moral responsibility for the treatment of Commandos, and complicity in the murder of Greek and Yugoslav civilians, including old people, women and children, in retaliation for Partisan activity. But again, no proof has been adduced, either by Herzstein or by the commission, that as a political analyst on the army staff, Waldheim had any but the most marginal involvement in the reprisals in the Balkans, or in the crimes committed by the Croatians under the mantle of the German occupation: forced conversion of hundreds of thousands of Orthodox Serbs to Roman Catholicism, deportation of many thousands of others – including all the Jews they could find – to concentration camps and forced labour, and the murder, on the Nazi pattern, of the most helpless and ‘useless’ among them.

What did Waldheim actually know? There can be no doubt that he knew all about the reprisals against civilians and the deportations – into forced labour – of Yugoslavs, Greeks and, after Italy’s split with Germany, Italian soldiers. Equally, of course, he knew of the deportations of Jews. But Professor Herzstein feels, as I do, that – contrary to claims by American officials of the World Jewish Congress, who, one must conclude, simply don’t understand wartime Europe-Waldheim would not have known about the ‘Final Solution’. The fact is that, except for civilians and soldiers in close proximity to the Einsatzgruppen in Russia, the gas-van murders of women and children in Serbia or the death camps in Poland, ordinary Germans and Austrians, including Army staff, did not know about the extermination of the Jews. There were rumours and guesses. As of October 1943, after a horrible speech by Himmler in Posen, the German Gauleiters knew. And a year later, in October 1944, he made accomplices of the generals by telling them. But until then, what would become the Nazis’ greatest shame was their deepest secret. And it is almost grotesque to reason that a young intelligence officer in the Balkans ‘must have known’ about this horror because a Jewish cemetery had been obliterated, and a quarter of the population of a city (Salonika) had manifestly disappeared, when he returned there, two months after the sinister operation was over.

Herzstein provides some very interesting thoughts, though Waldheim – who cannot now afford to ‘admit’ anything – will reject them too, even though they are in his favour. One is that in all probability he was an ‘American asset’ after the war – which would have facilitated his clearance for work at Austria’s Foreign Office, and for his later election to the United Nations post. Another is that the Yugoslav ‘war crime’ allegation (which was never followed up, and indeed was forgotten by Tito, who years later awarded Waldheim one of his highest decorations and repeatedly entertained him for weekends on his island retreat) was a purely political move – not against Waldheim but against his then boss, Foreign Minister Karl Gruber, who was successfully lobbying the Americans and British to oppose all the territorial and financial claims which Yugoslavia was making against Austria.

Finally, Dr Herzstein quotes one occasion when the 24-year-old Waldheim – in an exceptional, indeed, he says, possibly unique, initiative by a young staff officer – objected in writing to the German policy of random retaliation against civilians in Greece: ‘The reprisal measures imposed in response to acts of sabotage and ambush,’ he wrote in his report to the Chief of the General Staff of Army Group E on 25 May 1944, ‘have, despite their severity [Waldheim’s italics], failed to achieve any noteworthy success ... On the contrary, exaggerated reprisal measures undertaken without a more precise examination of the objective situation have only caused embitterment and have been useful to the bands ...’ For Herzstein the objection, though ‘not couched in moral terms’, was ‘moral in inspiration’. Given the situation, no other phrasing was possible, not would it have been in Waldheim’s character to have expressed himself more boldly. The ‘moral’ decision was the italics.

We are now at the tail end of a political manoeuvre that has got out of hand. The truth of the Waldheim scandal, as I see it – a truth underrated by Dr Waldheim despite his political experience – is that the real focus of bitterness is not Waldheim himself but the millions of Austrians who fifty years ago welcomed Hitler (to his own amazement, we now know) with frenzied jubilation, and whose joy only faded with the years because he lost – not because he was evil and they had been wrong. ‘I remember the first mass meeting I went to,’ Waldheim told me. ‘I heard screams and watched, horrified and afraid, and I said to my brother: “It’s hysterical, vulgar, undignified, unnatural – it’ll end badly.” ’ No, he was not a Nazi, but has he yet to grasp that these were not the right words for what he saw?

‘To a remarkable extent,’ Herzstein writes, ‘Waldheim is Austria.’ Like Austria he is intelligent, politically astute and ambitions in that rather special Viennese style which pre-supposes compromise and rejects ruthlessness. He is not imaginative, nor is he endowed with the capacity for moral excitement which is the essential prerequisite for commitment to a cause. Rather than arrogant and abrasive, as he has been described, I found him forlorn: nonetheless, aware that having been so close to the source of the horrors in the Balkans could affect his career, he lied for more than forty years about his war. And when one looks for signs of real feeling in him, what one finds are the engrained prejudices of his background. Herzstein suspects that something embarrassing, though not a war crime, may yet be revealed about his service in the Balkans. I doubt it. I think that he was confronted by sights he didn’t want to see and heard things he didn’t want to know.

I don’t believe it was anything specific that he did which Waldheim is afraid might be discovered. He is afraid of the memory of what he did not do, of what he was incapable of doing. And perhaps, too, of the slow realisation that while the stiff ‘I regret’ he has repeatedly pronounced these past months is not enough, it may be all he can manage.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.