In 1975 Colin Ward described Spitalfields as a classic inner-city ‘zone of transition’. Bordering on the City of London, the place had traditionally been a densely-populated ‘service centre for the metropolis’ where wave after wave of immigrants struggled to gain a foothold on the urban economy: Huguenot silk weavers, the Irish who were set to work undercutting them, Jewish refugees from late 19th-century pogroms in East Europe, and the Bengalis who have settled in the area since the 1950s. Since 1975, Spitalfields has achieved a national reputation as a reclaimable area of beautiful houses and exotic contrasts which has survived the levelling embrace of the welfare state.

I made my first encounter with the contemporary perspectives of the place a few years ago when visiting Christ Church to attend a concert in the Spitalfields Festival. Just getting into the building proved interesting enough, not least because the approaching concertgoer could hardly avoid the attentions of a more regular group of supplicants also gathering in the evening shadows of Hawksmoor’s massive church. This is the derelict congregation of the crypt. Its members attend a soup-kitchen famous from the days when the churchyard was known as Itchy Park, and now providing the only regular service offered here. Ignoring the ancient injunction bidding them from the wall to ‘Commit no nuisance,’ these time-honoured figures stage a performance of their own. They hurl insults at the concertgoers, begging money from them obscenely, and urinating over their smart cars. My sleeve was taken by a man who dragged me into the hellish narrative of 22 years spent in jail. Shuddering with horror at the deteriorated company into which he had been released, this fellow declared his own outlaw ethic in words that for me will always be cut into the stone of Hawksmoor’s building: ‘I’ve never raped. I’ve never mugged. I’ve never robbed a working-class home.’ As he sank away towards the underworld of the crypt, we ascended the hierarchical steps to hear music by Messiaen and Hans Werner Henze. The frisson was undeniable.

Earlier this year I went back to visit the disused synagogue at 19 Princelet Street – a rather dilapidated building now owned by the Spitalfields Trust and leased out as a ‘heritage centre’ concerned with the local history of immigration. Above the tiny synagogue is the room of David Rodinsky, a Polish Jew of increasingly mysterious reputation. Latterly described as a translator and philosopher, he is said to have lived here in some sort of caretaking capacity. One day in the Sixties Rodinsky stepped out into Princelet Street and disappeared for ever. His room has since become fabled: a secret chamber still floating above the street just as it was left. Caught in a time-warp of the kind that property-developers are quick to straighten out, it has become the new Spitalfields version of the Marie-Celeste.

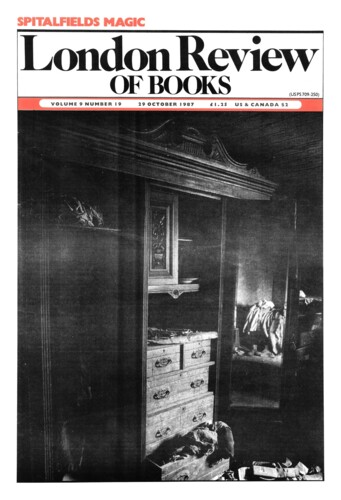

Rodinsky’s room is certainly there to be seen by the insistent visitor: ragged clothes still hanging in the wardrobe, a fur dangling down through the collapsing ceiling, a pile of 78’s, lamps and odd bits of candle, an old gas mask, scattered and prophetic-looking books in Hebrew, Russian, Hindustani. Among junk heaped up on the table lies a Letts pocket diary designed for schoolchildren and dating from 1961: a little memento to life as it was before the Filofax arrived. Rescheduled in pencil according to the Julian Calendar, it has been marked in cuneiform and adjusted to commemorate such remote dates as the Armenian New Year. The back pages (left to be filled in under printed headings like ‘pocket money’ or ‘films seen during the year’) are covered with scribbled commentaries on texts from the Ancient Near-East. They talk about Hittite Kings and the Citizens of Ur. From the window one can see broad-roofed Huguenot weaving-lofts outlined against Hawksmoor’s church. A mile or so beyond looms a larger sight that Rodinsky was spared: the 52 floors of Richard Seifert’s Natwest Tower, double-decker lifts, automatic window-washing facilities and all.

Here again was the characteristic frisson of the zone of transition, where different worlds rub up against one another, languages intersect on every corner and psychotics jabber in the street. Street lighting may have been improved after the Ripper killings of 1888, but Spitalfields remains a place of unpredictable encounters – full of intriguing little surprises as one unlikely appearance gives way to the next. The story of Rodinsky’s disappearance becomes a post-hoc fable of the gentrifying immigrant quarter. The Huguenots have gone, leaving only these delightful houses. The Bengalis will need stronger magic if they are to pull off the same disappearing trick. As for Rodinsky, did he evaporate romantically into thin air, or was he struck down in the street: a dishevelled victim of attack or sudden illness, a body found in the vicinity of Itchy Park and dealt with by the appropriate authorities?

The aesthetic, or rather the ‘life-style’ focus, which has brought Spitalifields into the Sunday magazines in recent years concentrates on the newest arrivals. Occasional television films from the Sixties show the indigenous white population leaving for Essex with relief, but the more profuse coverage of the last few years tells the different story of rundown Huguenot buildings being lovingly restored and re-established as private homes. Established in 1977, the Spitalfields Historic Buildings Trust held its tenth-anniversary meeting on 26 September. A hundred and fifty people (and not one black face among them) gathered at Truman’s Brick Lane brewery to celebrate the organisation which had, in the words of its current chairman (Francis Carnwarth, the personable banker who took over from Mark Girouard), ‘saved 18th-century Spitalfields’. There were warm memories from the early days of art-historical activism: the squats and sit-ins which the Trust’s members undertook as they confronted the vandalism of private developer and municipal authority. From these beginnings the Trust went on to bring credit facilities into an area which had been ‘red-lined’ by banks and building societies. It emerged as a campaigning property company, able to buy buildings, refurbish them with a care for the minutest period detail, and resell them under covenant.

The new immigrants form a mixed and largely agreeable group, and they certainly didn’t buy into the area just to make a killing. But if it takes historic preservationists, avantgarde artists, gays and other obsessive or bohemian types to put up with the years of chaotic living which are needed to re-open dishevelled areas like Spitalfields, the estate agents are never far behind. Like the first loft-dwellers in Manhattan, these early settlers are the pioneers of a larger revaluation which they may detest, and may manage to steer for a bit, but which soon sweeps over their ears. West of Commercial Street, the sanitisation already looks complete. To the east in Fournier Street, sensitively-refurbished houses are now coming up for sale at £400,000. With the approaching redevelopment of the Spitalfields Market site, it even looked for a while as if Hawksmoor’s church would be re-positioned – picked up as a piece of authentic history and placed like a quotation at the end of a vista in the Classical scheme which Quinlan Terry proposed for this 11-acre area. In the end, however, the Corporation of London has favoured the high-density scheme of Richard MacCormac, an architect who is also on the Council of the Spitalfields Trust. As the anniversary meeting of the Trust was told by an early and now dissenting member, Raphael Samuel, the conservation of Georgian buildings and the total clearance of local ways of life turn out to be two sides of the same coin.

The rising property market threatens Spitalfields with an altogether more devastating uniformity than welfare state regulation could ever have achieved. In the early stages, however, the thrill of unlikely co-existence is part of the attraction. It was at this point, a couple of years back, that ‘New Georgianism’ came in: taking preservationism and remodelling it to fit the perspectives of an emerging yuppie life-style. The starting-point was disparity and contrast: the miraculously surviving 18th-century house played off against the municipal oblivion which had failed to engulf it. The New Georgian aesthetic made a special point of the interior of the reclaimed house, valuing it as a private realm of clobber, candles and coal fires, and setting it off against a public world given over to destructive modernisation. Thanks to the Spartan settlers of Spitalfields, even the starkest imagery of the unimproved slum interior could be recovered. Squalor was authenticated and ‘saved’ from the welfare state which had threatened to finish it off for good.

The individual cameos are familiar enough. Dan Cruickshank, art historian and distinguished opponent of the Sixties bulldozer, lives in Elder Street protecting his early 18th-century wall-panelling from the wiring and plumbing of excessive modern convenience. Dennis Severs has gone further and reconstructed behind his door in Folgate Street the imaginary candle-lit world – ‘a collection of atmospheres’ – of an 18th-century family. A few streets to the east, Jocasta Innes has been busy reviving traditional decorative techniques on her own walls: following up the wholesome concerns of her early book The Pauper’s Cookbook with Paint Magic, an influential primer on antique methods of home improvement. The sequence emerging through these covenanted houses is precise. Rodinsky’s room is crossed with Calke Abbey, filled with junk and ghosts of a cleaned-up historical kind, and then refracted into the designerish style of magazines like The World of Interiors or Traditional Historical Decoration.

Out in the street that agreeable sense of disparity has also been going through its paces. Sliding alongside each other, like the panels in one of those flattened Rubik cubes by Fournier Street residents Gilbert and George, the appearances are caught in a shifting display of incongruity and juxtaposition which mocks old ideas of causality or of a unified social reality. The visible signs of what used to be called inequality are re-established as cultural exotica – a performance in the retinal theatre of the yuppie flâneur. Alexandra Artley, co-author of the diverting New Georgian Handbook, has gone on to make a distinct journalistic style from this rather beady-eyed form of social observation: one with which she adorns the Spectator.* Dwarves in Clerkenwell or broken-down Asian mothers in King’s Cross supermarkets – the present-day metropolis is full of exposed targets. The contemporary Spectator can objectify them as freaks, but Alexandra Artley can also bestow humanity on them – insisting upon it as the sincerely meant gift of her own Itchy Park prose.

There are some – and not just reluctant New Georgians – who dissent from all this. Prince Charles, who recently toured the area with Business in the Community, has come out against the new aesthetic. But the age of the bleeding heart is over, and this Royal whinge about the conditions in which many Bengalis live and work was too much for one resident of Princelet Street. Charles Clover, self-declared yuppie and environment correspondent of the Daily Telegraph, hit back in the Spectator (11 July 1987). Spitalfields is altogether more dynamic and enterprising than the sullen and uniform slums that exist where the welfare state got better-established. It was only the poverty of the area, and the fact that health and planning regulations were never properly enforced, that enabled the Bengalis to gain their slight economic foothold in the first place. And anyway, 95 per cent of these Bengalis come from Sylhet, the most backward part of Bangladesh. Whole families may indeed share single rooms and even beds in Spitalfields, but this is exactly how they live in Sylhet as well. Rather than complaining that conditions were ‘almost as bad as those on the Indian sub-continent’, the Prince should evidently have learned the real lesson of Brick Lane: in the urban economy as much as in any flourishing Indian restaurant, variety is the spice of life.

Iain Sinclair is himself no stranger to marginal commerce, but his route into Spitalfields is different. A glance at his early writings reveals that he started out in the ‘Poundian revolution’. Here are ample signs of American contamination: the parentheses that never close, the borrowed cosmologies and hermetic speculations of a young writer who seems to have heeded Jack Spicer’s advice and read the weirdest stuff on which he could lay hands. There were no job offers from Chatto or Faber for this particular poet, but in the Sixties at least there were casual openings in the East London labour market: cutting municipal grass, packing cigars in Clerkenwell, rolling barrels about in Truman’s Brick Lane brewery. So Sinclair went to ground in the manner of his own narrator: ‘seeking failure, and obscurity, as the only condition spiritually adequate to his self-esteem’.

This position became increasingly difficult to sustain as the Seventies progressed, and Sinclair was forced even further back onto his own resources. He emerged as a dealer in first editions, but not one of those ‘booksellers to the country houses of England, the libraries of Nebraska’, who operate at the top of the market. Sinclair is withering about these types: reputation brokers who sneer at their customers’ hopeless obsessions while all the time pricing up their own ‘quite amusing little collections of Uranian verse’. White Chappell opens in testimony to a different side of the trade. A carful of posthumous and fugitive men from the Sixties drift around the country, looking for deals. They pull off the Al to visit another fixture of the dead poetic. Mossy Noonmann is a veteran of Olson’s courses at Buffalo: a draft-evader who came in through Liverpool and finally got washed up in the ‘cheese-coloured’ English town where he runs an abject bookshop and family.

Sinclair offers a fetching portrayal of this world, dividing its genius between ‘the two best scalpers of their generation’: Nicholas Lane, a former rock musician who survives on cocaine, and Dryfeld, a figure who found his name in the Whitechapel Library. Without fixed abode or even substantial bodily form, Lane and Dryfeld are ghostly presences who slip the net of social identity. They are also masters of appearance, always turning up ahead of the horde in the frantic search for finds. Recognising no ‘intrinsic values’ beyond customer demand, the book market is a ‘world metaphor’. A Poundian echo declares Lane symbolic of his civilisation: ‘gone in the teeth, but brilliant in eye and finger’.

As the Seventies progress, every point of exchange, every place of possible discovery, is cluttered by swarms of lesser figures who come ‘wholly into their own in the bleak days of enterprise zone capitalism’. The ‘Outpatients’ are helpless wrecks who spill out into the street markets in the spring. Plunged into the ‘new world of deals’, they ‘buy at the bottom and polish the prices’, becoming more and more manic as the summer progresses and staggering back into whatever institutional care the welfare state can still offer them for the winter. The ‘Scufflers’ pose a more serious threat. Also known as the ‘Stoke Newington austerity freaks’, they pour out of N16 and turn the various markets over, haggling over every price, fighting over the position of their tables and generally killing the trade. It’s only a few years before ‘all the floating street literature has been trawled in and priced out of the range of any remaining students who might like to sample it. A cultural condom has been neatly slipped over the active, the errant and beautiful tide of rubbish.’

The movement of books through the markets of Farringdon Road or Brick Lane invokes other circulations that cut across conventional delineations of time and space. Sinclair’s Whitechapel is indeed a zone of transition – a place of partly occult circulation where the routes of many subcultures interconnect: books, drugs, immigrants, the Krays, doctors ancient and modern, even the Angry Brigade, who played out their version of ‘The Masque of Anarchy’ in the twilight world of the squatting/dole nexus. Its streets are shadowed by water: subterranean streams, the river with its old connections linking Spitalfields market with fertile fields in Essex, the cholera bacillus seeping unknown through both. The Ripper still hovers in the area – his movement caught in ‘the breath of the stones’ – while unearthed shrieks haunt the night.

The sites composing Sinclair’s London are various: old plague pits that went on to become the burial-ground of poets, the London Hospital on Whitechapel Road (steps like an opera-house, and dedicated to ancient rituals of surgery and pain), the pubs of the Kray circuit, Christ Church, the spots where the Ripper struck, the improved dwellings of 19th-century philanthropy, buildings that no longer exist. Many of these sites are orthodox points of identity in a knowable geography, but are also imagined as occult reservoirs where time itself is coiled. They run two ways – earthing the life of the city, while abstracting and raising it up to the stars. Sinclair’s Brick Lane may be full of chicken feet, cardamom and National Front slogans, but a wood is also superimposed along its length.

Between these sites move the figures of Sinclair’s narrative. Some are ‘presences’ which have escaped from the writings of Conan Doyle, Stevenson or Rabbi Loew. Like the figures from Blake’s Jerusalem that spill into the London of Sinclair’s Suicide Bridge (1979), these are fictions which, having ‘laid out a template ... more powerful than any local documentary account’, have gone on to find ‘independent life’ in the world. Others are precipitates of the history, rumour and memory which were still clinging to the streets of Whitechapel as Sinclair knew them in the Seventies. Up from the river comes John Gull, an early 19th-century Essex wharfinger who soon succumbs to cholera. Adopted by a parson and educated as a doctor, his son William turns up at Guy’s Hospital playing hand to the mind of James Hinton – a surgeon in whose philosophy the Ripper’s role as ‘time’s abortionist’ is first outlined. White Chappell is preoccupied by the Ripper murders, but Sinclair is not seeking to trace out the true identity of the Ripper: a question still being pursued by hacks who, with the centenary approaching, try to cash in on ‘long-delayed occult frisson’ by offering fresh readings of the butchered women’s underwear. A true scavenger, Sinclair is happy to raise the tacky speculations of a Ripperologist like Stephen Knight into his prose, but he then reverses the conventions of this sort of writing. Instead of unravelling its given crime, following the threads through to unmask the perpetrator who was there all along, White Chappell ‘starts everywhere, assembling all the incomplete movements ... until the point is reached where the crime can commit itself’.

Unchecked by anything so crippling as good taste, White Chappell is a Gothickly-entitled guidebook to the abyss. Its contracted and improvisational prose burns with radioactive energy as it proceeds through one loathsome fission to the next. Sinclair uses all sorts of heretical imagery to conjure the occulted spirit of his place: tarot and mandala symbolism, alchemical signatures and correspondences, treated texts (from Conan Doyle to Rimbaud), angelology and the metaphysics of light, ley-line millenialism, creeds and cosmogonies from Asia and, of course, the Ancient Near-East. Like his own obsessed surgeon, he turns from Baconian ideas of collection and arrangement, favouring instead the approach of the ‘Hebrew seer of old, penetrating through appearances to their central cause’. His Brick Lane is not a zone of exotic discovery, but rather a place of strange gnosis and hideous recognition in the night. Sinclair comes altogether closer to Rodinsky’s diarised thought than to the posthumous cult of his room.

If all this resolved into a metaphysics of belief, it could safely be dismissed with a contemptuous shudder – further proof, perhaps, that the so-called ‘Modernist’ tradition in American-English poetry has degenerated into the irrational creed of a dismal little sect. But despite his growing reputation as the abracadabra man behind Peter Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor, Sinclair doesn’t write as a believer either here or in Lud Heat (1975). Placing his own necromancy closer to the tradition of Rimbaud than to that of Madame Blavatsky, he uses myth to cut through contemporary closures: to drag Brick Lane back through the tide of incomprehending development which is engulfing it.

Dérèglement is an old trick in the book of Modernist technique, and it certainly can’t be commended for itself. Indeed, it has been used to justify too many self-referring literary texts of the sort that merely vaporise practical conceptions of reality and history. Sinclair saves himself from this outcome by stepping into his own writing and standing firm as the Narrator who has lived twenty years in this place full of demons. Thus Lud Heat’s occult reading of Hawksmoor was not just a literary conceit articulated in the image of historical buildings: it was written in the day-book of a man employed by the Council to cut grass in the shadow of these buildings, and its rationale was autobiographical. White Chappell works the same uneasy combination, portraying a place which keeps disappearing into myth but which also becomes paradoxically real as it does so.

For Iain Sinclair, as much as for the Spitalfields Trust, it is in the Brick Lane brewery that this movement is most effectively expressed. Sinclair worked as a labourer in the ullage cellars during the last days of the old brewery, and the legacies of its past as a family business (Truman, Hanbury and Buxton) were everywhere. The building was a rundown edifice, with stables and horses intact. There was a concessionary bar where drivers would tank up on free beer before heading out to make deliveries. As Sinclair found, a strong sense of locality survived in this world of rough male conviviality: memories arcing back to the 19th century, diverse mythologies of place, carnal fantasies played out in the pubs along Brick Lane. With its hidden rooms and generally unrationalised interior space, the brewery is easily designated a labyrinth. But the occult narrative is not simply artificial. Like the preoccupation with the Ripper killings, Sinclair finds it in the lore of the work-force and raises it into his prose from there.

It is in the autobiographical dimensions of this writing that the mythical presences are finally brought to ground. Far from being just an affectation of literary style, the real occultation of the brewery is the practical consequence of modernisation. There was a takeover in the Seventies and in the new age of Maxwell Joseph production was rationalised and assets realised (right down, apparently, to the portraits of old brewmasters which used to hang in the building). The frontages of the old brewery were incorporated into the Post-Modern structure which stands there now, mirroring itself across the abstract space that it has made of Brick Lane.

Such is the paradoxical realism that emerges at the heart of Sinclair’s conjured grotesque. The occult invocations and the florid historical fantasy both press back through this autobiographical connection to couple rudely with aspects of Whitechapel’s present condition. Contemporary ideas of benevolent reform are ghosted by the hideous drama of Sir Frederick Treeves, the London Hospital doctor whose philanthropic adoption of the Elephant Man is portrayed as a self-interested experiment in soul murder. Post-war ideas of planned redevelopment are confronted by the mocking inscription on the façade of a 19th-century improved dwelling – ‘Labour/is life/blessed is he/who has found/his work’ – a tablet commandment which doubles as the credo of the Ripper. As for conservation, here is freakish morbidity indeed: pickled in a jar at the London Hospital Medical College Museum.

So the occult is brought over into contemporary Whitechapel, finding its true occasion in a place which is full of unfinished business: littered with fragments of its own alienated history, the subjectivity of its population surplus to new requirements. The real abortionists of time are found here in the forces which are detonating the old warrens, covering them as may be with ‘respect, modesty and forward planning’, and suspending the city in ‘the time of the ending of time’. White Chappell is offered as the realist prose of a city lost between the welfare state, monetarism and the big bang. When pragmatic reality goes Baroque, Hawksmoor’s long neglected churches finally come into their own.

There are no resolutions in this book. Indeed, one can sense the relief at the end when Sinclair finally steps out of his own London poetic. After years of ‘mantic trembling’, this human lightning conductor emerges in the unlikely guise of a family man, planning a much-deserved sojourn in the country. Meanwhile, as he looks back in the direction of Spitalfields and sees even his own poetic being refurbished to fit the New Georgian age, he can at least rest assured that he has left some truly contrary perspectives behind him.

Ackroyd’s Hawksmoor stripped Sinclair’s mythology from its autobiographical occasion, abstracting it into a more purely ‘literary’ form of expression. Full of the frisson of occulted history, this best-selling fable of cursed enlightenment has an unspoken contemporary meaning which emerges clearly in the contrast with Sinclair’s writing. The Fire of London comes up to find its equivalent in the Blitz (when, as one of Sinclair’s brewery workers recalls, bombs even unearthed the dead in the Jewish burial ground). The rebuilding of the city also drifts forward in time: the early 18th-century Commission for the Building of New Churches merging with the redevelopment programmes of 1945. As for the curse, this migrates from Hawksmoor’s churches and obelisks to become a positive blight on the present. Ackroyd repopulates Spitalfields with properly English children who recite Opie-like street rhymes as they walk past Christ Church. He then invites his ample audience up into the church where he will perform the final disappearing trick on History itself. Iain Sinclair won’t be there to hear the joking asides about those deluded occultists who still hold out for ‘intrinsic values’ in a world of all-consuming pastiche. By the end of White Chappell, he has knocked down a signed copy of Hawksmoor for a fiver, stuck the story of Chatterton into the mouth of a demented Southwark barman, and moved on.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.