When Mussolini was making his last desperate flit from Milan in April 1945, Nicola Bombacci, his old comrade – the two men had been revolutionary socialist schoolteachers together thirty years before – climbed into the Duce’s car carrying only a small suitcase. ‘What else would I need?’ he said. ‘I am an expert in such matters. I was in Lenin’s office in Petersburg when the White troops of Yudenitch were advancing on the city and we were preparing to leave, as we are doing today.’ In the space of a quarter-century Bombacci, an old Communist and Comintern hand, had progressed right across the ideological spectrum, beginning as an intimate of Lenin’s and ending as an adviser to Mussolini: by fluke he stood next to both men in their supreme hour of crisis.

Probably only the 20th century, with its rapid and immense revolutionary convulsions, has produced biographies as extraordinary as this. But even in our century floaters who drifted across from Communism to Fascism were oddities. On the other hand, how does one understand the process by which a major Communist leader became a major Fascist leader? To anyone who has pondered this question the career of Jacques Doriot has always had a special fascination. Now Jean-Paul Brunet has ransacked just about everything – including police files – in order to put the full story together. He has an amazing story to tell.

Doriot was the only child of a working-class family, his father a blacksmith forced into factory work and a man of anti-clerical views, his mother a devout Catholic who ensured that her son became an altar boy. Jacques, a tall, painfully thin boy, left school early to become a factory worker in St Denis, the most proletarian suburb of Paris. This perfectly ordinary career was changed for ever by his call-up in 1917. He fought heroically at the front – an experience which scarred his life – and was then retained in the Army after the war, to be sent with a French expeditionary force to put down Bela Kun’s Soviet republic in Hungary (and instal the noxious Admiral Horthy in power), to help D’Annunzio in Fiume, and then to put down partisans in Albania. By this stage he had had more than enough and was jailed for a month for indiscipline.

Returning to St Denis, Doriot became a moderate member of the Young Socialists, but his strong autodidactic urge found expression in an endless diet of Western penny dreadfuls rather than in the political classics. Politicised by war, but also confused by it, he earned a greater reputation for a love of adventure and drama than for radicalism. When the Socialist Party voted to become the Communist Party, Doriot moved with the majority and, growing prominent in the Young Communists, was sent to Moscow in 1921 for the Comintern Youth Congress. The experience transformed him. He met Lenin, received extensive training in Marxism, learnt speech-making, German and some Russian, and generally went through an accelerated Communist higher education. Selected as a promising young cadre, he spent 20 months in Moscow, working closely under Trotsky, who became his friend. Above all, Doriot venerated Lenin and took it very much to heart when Lenin chided him in fatherly fashion for becoming too dogmatic. When Lenin died Doriot cried publicly and unashamedly.

By the age of 23 Doriot was a member of the Presidium of the Comintern Executive. Zinoviev, harassed by the endless leadership squabbles of the French Communist Party (the PCF), looked on the ascetic young Doriot as a dependable revolutionary, commendably tough and cynical in his involvement with the covert side of the Comintern’s activities, and quite understanding about difficult comrades who had to be ‘disappeared’. Here was the PCF leader of the future – a view Doriot shared.

Returning to France, Doriot devoted himself to a series of anti-militarist campaigns, first among French troops in the Ruhr and then in the Rif. These campaigns – aimed at getting soldiers to desert and to show solidarity with the occupied populations – earned him considerable notoriety, the unrelenting hatred of the French military establishment, and a series of prison sentences for treason. He became, as it were, the Scarlet Pimpernel of the PCF – leading the PCF Youth, sitting on the Party’s Politburo and addressing meetings, all while on the run from the Police, using a series of aliases and sleeping where he could. Finally caught and sentenced to 34 months’ jail in 1923, he continued to write incendiary anti-military articles (earning him further sentences) until the PCF put him up as a candidate in the 1924 elections. An embarrassed President had to release him when the working-class voters of the Paris banlieu, among whom he was already a popular hero, elected him by a very large majority. He immediately became a parliamentary enfant terrible, proudly announcing that he considered himself a soldier of the Red, not the French Army, and generally seeking every occasion to provoke paroxysms among bourgeois Deputies and the non-PCF press. A powerful and charismatic speaker, he gloried in sheer intransigence, drew large crowds wherever he went, and, noticeably more than any other PCF leader, was always in the midst of the violent confrontations which quite routinely occurred in the course of PCF marches and demonstrations. On one such occasion Doriot was so badly beaten by police that he had to be hospitalised while in jail – but one policeman also died after, so it was claimed, Doriot had kicked him.

Doriot raised eyebrows within the PCF as well. His revolutionary fervour was exemplary but his style was undeniably self-advertising and his ambition was clear. It was noted, too, that when, in between jail sentences, he got married (to a PCF militante), the ceremony – amazingly for a PCF leader – took place in church. He moved his now-widowed mother into the new marital home, where she became a Catholic materfamilias to his two daughters.

Besides running the PCF Youth section, Doriot had responsibility for colonial questions, exercising a wide influence on young revolutionaries throughout the French Empire. One young Vietnamese who came under his wing carried the alias of Nguyen O Phap (‘the peasant who hates France’). Doriot suggested that this be changed to the more diplomatic Nguyen Ai Quoc (‘the patriot’). This protégé became better-known as Ho Chi Minh.

Doriot himself had originally been a protégé of Trotsky, but transferred his loyalties to the Comintern chief, Zinoviev, as Trotsky’s star waned. Returning to Moscow in 1925, he was quick to abandon Zinoviev for Stalin, who invited him to a private supper in the Kremlin and advised him to build a political base of his own. It might seem that being high up in the Comintern was enough, said Stalin, but one had to realise that in Soviet eyes Comintern operatives were mere employees. A man who could command the loyalties of a whole town or district was bound to count for more. Doriot returned home in cynical mood, reflecting that his meteoric career in the Comintern was counting for less than he’d hoped and that the PCF leadership to which he aspired would be settled by men in Moscow with their own peculiar set of criteria.

The turning-point probably came with Doriot’s trip to China on a Comintern mission in 1927. Loyally toeing Stalin’s pro-Kuomintang line, the mission deliberately failed to warn the Chinese Communists that it had come across hard evidence that the Kuomintang was about to turn on them. The Shanghai massacre took place shortly afterwards and Doriot, on his return to Moscow, incautiously told friends that Stalin’s policy in China had been an utter disaster and the mission a disgrace. This seems to have got back to Stalin, who never fully trusted him again. An icy reception awaited him on his return to France, and the next year Thorez was confirmed as the PCF leader. Doriot was furious. Emerging from yet another spell in jail, he now openly attacked the Politburo’s new ‘class against class’ line and questioned whether Stalin had any idea that this policy was ruining the PCF, causing both its membership and its electoral support to plummet. The Comintern representative who secretly attended this meeting of the Politburo was arrested straight afterwards on a tip-off which must have come from a Politburo member. The finger of suspicion points at Doriot: the Police said he had been the source and certainly he had a powerful interest in curtailing Comintern influence within the PCF.

From this point on, Doriot fought a sustained campaign against the Comintern line within the Politburo. Publicly he remained a loyal defender of ‘class against class’, for he was (rightly) certain that the policy was so suicidal that either it would destroy the PCF utterly or it would have to be reversed: in either case the fact that he alone had stuck out strongly for something more sensible would surely enable him to take over the PCF leadership. Thorez and his supporters fought back against this unwonted opposition, even at one stage forcing Doriot into a humiliating public autocritique. Meanwhile Doriot was still battling with the Police: he fought the 1928 elections while on the run, eluding the Police for four months while popping out of hiding to address election meetings. He was caught, jailed again, but again elected deputy for St Denis from jail. This time there was no remission. He emerged from jail to find that the Party had stripped him of his colonial and youth responsibilities and offered his resignation from the Politburo. This the PCF refused. It had lost over half its membership in only a few years, Doriot was publicly loyal and he was the Party’s only real star. He was too valuable to lose.

What Doriot wanted was to become mayor of St Denis: as député-maire of this proletarian redoubt he would have the base he needed. But the PCF made him campaign for faceless yes-men instead. A year later, the ruling PCF administration of the town split, causing fresh elections. Again, Doriot threw his huge popularity into getting another yes-man elected to the mayoralty he so badly wanted himself. This mayor, too, only lasted a year before being dismissed for financial fraud. This time there could only be one choice: in 1931 Doriot at last took possession of ‘his’ town.

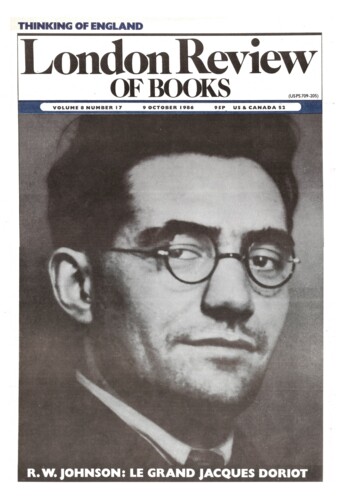

The result was astonishing. While the PCF’s vote and membership slumped everywhere else, in St Denis they soared. A massive social welfare and education programme was launched and the municipal payroll hugely expanded. Doriot’s benevolent but authoritarian figure was everywhere. He ran his own local paper, re-instituted civil baptisms (which he himself performed), had youth groups named after him, hobnobbed with the local curé, got on famously with local businessmen and allowed White Russian exiles and the local Fascist leagues to use municipal facilities. He was everyone’s friend. The Politburo ground its teeth. In Parliament Doriot now became so pally with Socialist and bourgeois Deputies that he got special government help for St Denis’s huge budget deficit. Suddenly the lean ascetic was no more: he developed a taste for good restaurants, wine, Paris night-life – and became fat. His striking height was now matched by corresponding width: to one and all, he became Le Grand Jacques. The Politburo made him take a Thorez yes-man (i.e. spy), Marcel Marschal, as deputy mayor. Marschal immediately fell under Doriot’s sway, becoming his loyal retainer and drinking partner. He was simply irresistible. Though publicly still loyal to the PCF line, in private he was bitterly cynical about Stalin and the Comintern. Not only did he tell the Politburo that Stalin’s policy was ‘imbecile and absurd’: he went to Moscow to repeat this blasphemy at a Comintern meeting. But he was the PCF’s star, and the Party endlessly used him as its major draw. He continued to brawl with the Police at demonstrations – a great, earthy proletarian giant who packed an awesome punch – and his personality cult grew apace. In Parliament, where he preached a national Keynesianism, Socialist Deputies promised him a ‘brilliant future’ if only he would switch to their side. He in turn was careful only to criticise the Socialists on such issues as their plan to limit the number of immigrant workers: ‘For me the word “foreigner” has no sense,’ he proudly declared. An unhappy Thorez had to watch as Doriot was elected leader of the PCF parliamentary group, head of the federation of PCF mayors and boss of the Party’s Central Control Commission.

In February 1934 Doriot made his break. At wildly enthusiastic mass meetings he urged that the Fascist danger was too great to allow the suicidal ‘class against class’ policy to continue. The fatal split between Communists and Socialists which had helped Hitler to power in Germany must not be repeated in France: there must, at all costs, be a popular front. The PCF leadership publicly condemned him for ‘crimes against the working class’. A worried Comintern summoned Thorez and Doriot to Moscow. Doriot insultingly replied that he was too busy with a municipal by-election to come. The Comintern was so eager to keep him on board that it swallowed even this. So Doriot demanded a public Comintern disavowal of the whole PCF leadership before he would come. This time he was expelled.

The PCF moved quickly to isolate Doriot in St Denis, where the local Party stuck solidly by him. For a while he still went on PCF demonstrations in Paris, but these were now a calvary where he was hooted, booed and needed bodyguards to protect him. His great trump card was that his call for a broad anti-Fascist front was immensely popular, but only a few months later the PCF swung round and adopted this tactic as its own, signing a pact with the Socialists and Radicals and warning their partners that any collaboration with Doriot would threaten the new alliance. He was frozen out. The Popular Front, for which he had so courageously campaigned, was now a threat to his political survival.

Under this pressure, Doriot’s political position evolved rapidly. Although the St Denis mairie still flew the red flag and Doriot still called himself a ‘national communist’, his attacks against the PCF, Stalin and the Comintern became increasingly bitter. When the Franco-Soviet Treaty was signed in 1935, Doriot attacked it as a scheme on Stalin’s part to lure France into a European war. Lenin, he said, had been a revolutionary genius, but Stalinism was merely Pan-Slavism in modern guise. What Stalin really wanted was dominance over Asia. He therefore needed a free hand for a war against Japan, which in turn meant that he needed France to keep Germany under threat. France’s own interests lay, above all, in keeping out of war. What mattered most was a rapprochement with Germany. So why not talk to Hitler? Those who wanted to place Hitler beyond the pale, who made everything conditional upon a doctrinaire anti-Fascism – i.e. the Popular Front parties – were simply playing Stalin’s game. The Popular Front had made itself Doriot’s enemy: it was not difficult for him to decide that it had become the enemy of France as well. Not surprisingly, French businessmen, frightened of the growing threat of the Left, began to see Doriot as a barrier against the Popular Front, and to make contributions to his cause. One of them even introduced him to Colonel La Rocque, leader of the biggest of the Fascist leagues. Doriot found La Rocque ‘politically naive’, but ‘a patriot, a fine French officer’.

Doriot’s rightward drift was probably constrained by the need to hold St Denis, the reddest part of the red belt. The PCF knew that without this base, Doriot would pose no threat and made every effort to dispossess him of it. An orthodox PCF branch had been founded there straight after Doriot’s expulsion and gradually ate into his working-class support. In 1935 Doriot had been triumphantly re-elected as mayor – right-wing voters flocking to him to compensate for the fact that he had held only 55 per cent of his old Communist voters. In 1936, despite the huge tide of Popular Front enthusiasm, Doriot just managed to hang onto his parliamentary seat – an astounding achievement – but the orthodox PCF candidate took over 48 per cent of the vote: Doriot was now very much the candidate of the Right.

Financial support for him now poured in. Le Roy Ladurie, head of the Worms bank, was a notable contributor, but the Verre, BNCI and Dreyfus banks chipped in, as did Rothschilds, Lazard Frères, the Banque de I’ Indo-chine, all manner of employers’ associations and business pressure groups, the De Wendel empire, the Comité des Forges, Rhône Poulenc, Mazda Lamps, and so on. All this money was poured into Doriot’s Parti Populaire Français (PPF), founded straight after the 1936 elections. The PPF claimed that its main enemies were the PCF and social conservatism: in practice, it evolved rapidly towards a pure form of Fascism. Even at its founding congress Doriot boasted that he ‘knew Mein Kampf well’, and he was soon soliciting (and getting) a large and regular flow of funds from Mussolini and, probably (though the evidence is less clear), from Hitler.

The PPF claimed, above all, to be social and national, demanding a strong national state as the arbiter between corporately represented professional groups. It was staunchly for the ‘defence of the working class’ – but also for the peasantry and the middle class ‘which constitute the very essence of the nation’. It favoured ambitious programmes of public education, hygiene and sport ‘in order to fashion a stronger, healthier race’. Doriot demanded a sweeping reinforcement of the French state and empire and French neutrality abroad under the banner of ‘France first’.

Above all, though, the PPF was built round Doriot. He was an electrifying orator. His clear and brutally factual style was reinforced by his awesome physical presence – in hot weather, sweating profusely, he would take his shirt off to speak, and his huge arms and body gave rhythm and cadence to his sentences. People often said that it was only by listening to him that they learnt what they had really been thinking. ‘One had the impression,’ said one admirer, ‘of being present at an enormous collective rape, effected by a power of elemental virility.’ A number of talented young men of the right – Drieu La Rochelle, Bertrand de Jouvenel, Alfred Fabre-Luce, Maurice Duverger* – clustered round him, mingling oddly with the considerable number of working-class and PCF militants he had carried with him: Marcel Marschal, once Thorez’s trusty agent, was now only one of six former Communists sitting on the PPF Politburo. The PPF’s secretary-general was Henri Barbé, who had succeeded Doriot as head of the Communist Youth section. From the outset the PPF was a party of leader-worship: members took an oath to the Leader, who was also mentioned in the party hymn (‘listen, o child of France, to Doriot, who calls you towards the noblest goal’). A Nazi-style salute was adopted to greet the Leader and party ceremonies made great play with a swastika-like emblem. The PPF exalted action, the necessity of violence, and instinct (‘the spontaneous force of life’) – all of which Doriot was taken to exemplify. Doriot never appeared now without large numbers of bodyguards – usually drawn from the PPF Action Groups (i.e. street-fighters), who in turn were recruited heavily from unemployed workers (especially North African migrants). By January 1938 the PPF claimed 295,000 members: it was probably the largest French Fascist party with genuine proletarian roots, though it became steadily more middle-class all the time.

Initially Doriot made a point of saying the PPF was not anti-semitic: it had ‘better things to do’ than fight the Jews. The PPF was, after all, receiving large funds from three Jewish banks – Rothschilds, Lazards and Worms – and Bertrand de Jouvenel (the key bagman for PPF funds from Mussolini) was half-Jewish. But the PPF had naturally attracted fierce anti-semites into its leadership, and its large following among the Algerian colons was furiously anti-semitic. Inevitably, the PPF’s anti-semitism became steadily more pronounced, and by 1938 Doriot was regularly referring to the phenomenon of ‘Judaeo-Bolshevism’. Business funds still poured in, but he also solicited secret contributions from the Police, in return for ‘special services’.

The PCF, meanwhile, had pressured the Blum Government into investigating Doriot for municipal fraud. This was to produce a wonderfully French political comedy. The inquiry revealed school heating bills for St Denis which were up to ten times the normal level – and corrupt arrangements with two local businessmen to whom the heating contract had been given. This had been going on ever since 1931, when St Denis had been under PCF rule, so the PCF must have known only too well what an inquiry would reveal. Doriot was revoked as mayor, resigned in a rage, and stood again in the by-election – but this time the PCF won. Doriot, utterly dashed, resigned as Deputy on the spot. The PCF won the parliamentary by-election even more resoundingly. However, Doriot’s revocation as mayor was then set aside on procedural grounds. Doriot naturally trumpeted this as a complete vindication of his innocence (which it wasn’t), and his cronies happily announced that Le Grand Jacques would become mayor once again. But to do that Doriot would have to win election to the council again – and it was clear he couldn’t win another election in St Denis. So, prudently announcing that he had a national destiny instead, Doriot refused to run. He put Marschal in as mayor instead and ruled through him.

Although Doriot had become steadily more sympathetic to Hitler, he readily joined up in 1939: to fight, he said, not against Nazism, but as a good French nationalist against Germany. Blessed with a commander who was a PPF sympathiser, Doriot returned home in 1940 with a Croix de Guerre. He immediately rallied to Pétain and eagerly sought a position in the new Vichy Government. To curry favour with the Germans he unleashed PPF toughs on a (premature) campaign of smashing up Jewish shops, hanging Freemasons in effigy.

Thereafter it was downhill all the way. Doriot was made a member of the Vichy National Council, but was always kept at arm’s length both by the Germans and by Pétain (who had never forgiven him for his anti-militarist agitation in the Twenties). Frustrated, Doriot turned to the SS and Gestapo as the ‘most revolutionary’ elements among the Germans, and sought to prove himself by continuously outbidding Vichy in extremism. When French Jews were deprived of their citizenship, Doriot denounced the law as insufficient and demanded that Jews be made to ‘cry tears of blood’: ‘scientific’ means and concentration camps were needed, he said, to ‘cleanse’ France of the Jews. In time he got his wish and the PPF eagerly volunteered to do work too dirty even for the French Police. From soliciting contributions Doriot moved to outright protection rackets and extortion and used the PPF as a spy network for the Gestapo, denouncing members of the Resistance in return for cash. He grew fat on the proceeds, indeed he had become steadily more obese, more and more addicted to night-life, to mistresses (by one of whom he had a child), and to brothels.

His great day came with the German war on Russia – Doriot cried tears of joy at the news. Against Vichy’s wishes, he organised the Légion des Volontaires Français to fight Russia and went off to war with them in 1941, hoping to emerge as the new (and this time successful) Napoleon, carrying the French flag on a great victory parade through Moscow. This dream took an initial knock when the Germans insisted that the LVF, Doriot included, should wear German uniform. Worse still was to come. The LVF, by the winter of 1941, found itself, ironically, at Borodino, where they suffered much the same fate as Napoleon. Within a month the Russians and the cold had killed half of them. The rest had to be pulled back from the front. Thereafter the LVF was only used against partisans, alternating between cosy unofficial agreements with their opponents and spasms of unspeakable atrocity against civilians. Doriot hurried back to Paris after just a few months, lighter by three stone, and only once appeared at the front again.

Doriot’s great hope was that the PPF – now really just a few thousand thugs, barely able to protect Doriot from the repeated assassination attempts mounted by Communist Resistants – would be declared the single party of the Vichy regime. Failing that, he hoped, at least, to be made Minister of Jewish Affairs. But the Germans realised only too well that Doriot was now probably the best-hated man in France: he was accorded the sublime accolade of a visit to Hitler in the Wolf’s Lair, but that was all. After D-Day he and his remaining followers fell back over the Rhine with the retreating Germans – during the train ride PPF militants competed for the favour of their German fellow-travellers with lovingly detailed accounts of the atrocities they had committed (some had been helping Klaus Barbie). Doriot was convinced that his moment had at last come. A Committee of National Liberation was set up to plan the Fascist restoration in France. (Doriot was furious at the German suggestion that they set up their headquarters in the Schloss Stauffenberg. How could he feel at home in a castle confiscated from the leader of the July plotters against the Fuhrer?) His days were spent in frantic intrigues over the composition of the future Fascist government of France and tugging at the sleeves of all who would listen to tell them that Hitler’s secret weapons would still win the war. Did they not know that there was a V3 rocket which could bombard New York? In the Reich’s death agony Doriot had somehow procured unlimited supplies of fine wine and food. He was still living extremely well when, in March 1945, the car in which he was travelling was straffed to bits by Allied planes. The faithful Marschal delivered the funeral oration over the almost unrecognisable corpse.

How to explain the career of a man who went from the extremes of militant Communist self-sacrifice to this Götterdammerung in the twilight of the Third Reich? There are three clues. One is sheer ambition: Doriot believed most of all in his own star. He would take second place to no one. What he wanted most of all was to be leader of the PCF – long after he had left the Party he would regale crowds of right-wing extremists with accounts of how he had been unjustly thwarted in that ambition. His systematic tactic for achieving his ends was the dramatic outflanking movement. He would show Thorez up by going endlessly to jail, by getting into street fights, by being more militant than anyone. Then he would outflank him by calling for a popular front when he knew the Comintern was not ready to allow Thorez to do the same. When Thorez did follow suit, the alternatives of submission or leaving to become a junior oddity in the Socialist Party were equally demeaning and thus unacceptable. He had to found the PPF, he had to be leader of a party, that immense ego had to be gratified. Later, he tried to outflank Pétain and Laval by displays of Hitlerite enthusiasm he knew they could not match. He was always consumed by the injustice of the fact that sheer militancy was never quite enough.

The second point is that Doriot was a classic inter-war political boss. As one reads of his rule in St Denis, one is irresistibly reminded of the political machines which ruled New York, Chicago, Huey Long’s Louisiana or even Leningrad in the same period. The pattern of rackets, extortion, jobbery through expanded municipal services, the ubiquitous bully-boys, the populist cult of the man of the people who has become the Boss, has a wide resonance. One wonders, even, how necessary politics was to it all. How different was Doriot’s little empire in St Denis from Capone’s in Cicero?

The final clue is surely Doriot’s size. While he was a revolutionary militant he was ascetically thin; when he became a Communist boss he became fat; as his career veered frenetically away from its origins, he became grossly obese. Food and drink are metaphors as well as necessities. Doriot’s increasingly rapacious intake of both must have been part-compensation, partly a matter of in for a penny, in for a pound: as one reads of the grossness of his later years one wonders whether sheer self-disgust may not also have played some part. But surely, too, it was a simple matter of self-fulfilment, of gratification of ego? We are told that inside every fat man there is a thin man trying to get out. Doriot may have been a case of the opposite: inside the ascetic revolutionary there was a corpulent high-liver dying to get out. What we know of Doriot’s sexual habits suggests a similar progression from puritan self-denial to grotesque over-indulgence. One wonders, too, about the significance of that early religious childhood, the marriage in church, the willingness to have his children brought up as Catholics, his friendship with the local curé even while a Communist, his Vichy-period glorification of the Church as the essential spirit of France ...

Probably Do not himself did not know the answers to these questions. Late in his career as Fascist leader, he still kept a portrait of Lenin at his bedside. Perhaps Lenin was the father he wished he had had. And despite all the grotesquerie of his later days, the memory of Doriot the heroic proletarian militant dies hard. Going round the Parisian Red Belt in 1967, I found that more than one Communist home still had pictures of him on the wall. Amazed, I asked a PCF organiser how this could be. He shrugged. ‘It’s not so unnatural,’ he said: ‘A une certaine époque il était une grande figure. Il était Le Grand Jacques’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.