Once we have located the cemetery the grave itself is not hard to find, one of a row of headstones just inside the gate and backing onto a railway. Flanders in April and it is, not inappropriately, raining, clogging our shoes the famous mud. The stone gives the date of his death, 21 October 1917, but not his age. He was 20.

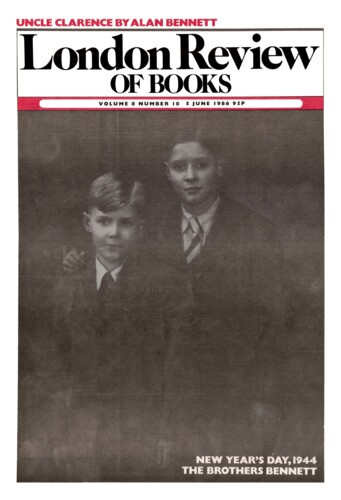

He was always 20 all through my childhood because of the photograph on the piano at my grandmother’s house in Leeds. He was her only son. He sits in his uniform and puttees in Mr Lonnergan’s studio down Woodsley Road, Lonnergan’s a classy place that did you a good likeness. Less classy but still doing a good likeness, Mr Lonnergan takes pictures of my brother and me in 1944 in the closing stages of the next war. An artier study this, two boys aged 12 and nine emerge from a shadowy background to look unsmiling at Mr Lonnergan under his cloth. My brother is in his Morley Grammar School blazer, his hand resting unself-consciously on my grey flannelled shoulder. In his picture Uncle Clarence is on embarkation leave from the King’s Royal Rifles. In 1944 we too are going away, though not to certain death, only ‘down South’ to fulfil a dream of my father’s. He has answered an advert in the Meat Trades Journal and having worked for 25 years for the Co-op is now going to manage a family butcher’s in Guildford. Uncle Clarence never comes back but we are back within the year, his photograph still standing on its lace doily, and now ours has been put beside it.

The piano itself does not belong to Grandma. She gives it house room at 7 Gilpin Place for her sister-in-law, Aunt Eveline. Aunt Eveline has never married and has beautiful hand-writing. Her name is on all the music in the piano stool, and in her time she accompanied the silent films at the Electric Cinema, Bradford. Come the talkies, she turns housekeeper and now looks after a Mr Watson, sometime chairman of the Bradford Dyers’ Association, who is a widower with a fancy woman, whom Aunt Eveline dislikes because she has dyed hair and is not Aunt Eveline. On Sundays there are musical evenings in the front room at Gilpin Place. The children are warned to keep back as a shovelful of burning coals from the kitchen range is carried smoking through the house to light the fire in the sitting-room before we sit down to high tea in the kitchen. After tea, the sitting-room still smelling of smoke, Aunt Eveline arranges herself on the piano stool and with my father on the violin (‘Now then, Walter, what shall we give them?’) kicks off with a selection from Glamorous Night. Then, having played themselves in, they accompany Uncle George, my father’s brother, in some songs. Uncle George is a bricklayer and has a fine voice and a face as red as his bricks. He sings ‘Bless this house’ and ‘Where’er you walk’ and sometimes Grandma has a little cry. These occasions go on until about 1950 when Grandma dies.

Grandma, whose name is Mary Ann Peel, has three daughters, Kathleen, Lemira and my mother, Lilian. Clarence is the eldest and the only son. Whenever he is talked of it is always ‘Our Clarence’ or, to my brother and me, ‘Your Uncle Clarence’. But he is only our would-be uncle, an uncle-who-might-have-been, not like my father’s brothers, uncles of flesh and blood, two of them veterans of the same war and very much alive. We are his nephews by prolepsis and he our posthumous uncle, protected even in death by the convention that children do not refer to relatives by anything so naked as their name. When Uncle Clarence’s name comes up it is generally in connection with the undisputed nobility of his character. What is disputed is which of the sisters resembles him most. It is accepted in our wing of the family that this role belongs to my mother, who certainly looks most like him. The prettiest of the three, she marries early and does not get on with the other two, who marry late. Clarence, later to become a silly-ass kind of name, a name out of farce, and like Albert never revamped, remains in our family the name of a saint. If my mother is asked about Uncle Clarence the reply is always: ‘He was a love. He was a grand fellow.’ What job he did in the few years given to him to have a job, whether he had a dog or a bike or a girlfriend, none of this I know or bother to ask and with both my aunties dead there is no one now who does know. My mother lives, but she does not remember she had a brother or even what ‘a brother’ is. When asked she still says: ‘He was a grand fellow.’ She says the same now about my father. I am a grand fellow too. In these her flat, unmemoried days she would probably say the same about Adolf Hitler.

In the front room at Gilpin Place is an elaborate dresser, with mirrors and alcoves and fretwork shelves. Stripped of its warm chestnut varnish, it will have gone up in the world now, moved from Leeds 12 to Leeds 16 to grace the modish kitchen of a Polytechnic lecturer or a designer at Yorkshire TV. In my time this dresser is laden with ornaments housing Grandma’s hoard of silver paper and the drawers are stuffed with bundles of seaside postcards: Sunset across the Bay, Morecambe; The Illuminations, Blackpool; The Bandstand, Lytham St Annes. Glossy, deckle-edged cards in rich purples and browns. To my brother and me who have never seen fairy lights along the prom or the sands without tank traps and barbed wire they are what the world was like Before the War. We take the cards and steam off any Edward VII or George V stamps to use as (pretty mediocre) swaps. Among the picture postcards are photographs on stiffer card: Grandma on outings with the ladies’ bowling club, striding along some promenade in a long, laughing line, big ladies in cloche hats and black duster coats on trips to Bangor or Dunoon.

The cupboard in the dresser has more mysterious artefacts: old scent sprays, cigar-cutters, some candle snuffers and a pile of ten-inch 78s in torn brown-paper covers. One is ‘I lift up my finger and I say tweet tweet, hush hush, now now, come, come’. I find some needles in the cupboard and play it on the wind-up gramophone in its red rexine cover. In theory the dresser is out of bounds and I can only look in it if my brother is out playing with his pals or swimming at Armley Baths and Grandma and I are alone in the house. This is generally on a Saturday afternoon. She dozes in front of the kitchen fire while I investigate the cupboard. ‘Rooting’ she calls it. From time to time she wakes up. ‘What are you doing in there?’ I say nothing. ‘Are you rooting? Give over.’

In the first year of the war there is a tin of biscuits in the dresser. The biscuits have long since gone but the legend of them remains and I always think if I can get to the very back of the cupboard there will be another tin that has been forgotten. There are plenty of other tins. When I ask what’s in them my grandmother always gives the same answer: ‘Chums.’ It is a joke which never fails to amuse her. But before I know that chums are friends they are something mysterious, sweet and secret, that one should not look for because forbidden.

Whereas the kitchen cupboard is dedicated to use, with the old familiar cutlery, thread-bare tablecloths and knives that years of sharpening have brought to the width of skewers, the front-room cupboard houses stuff that never gets used, often in sets: the set of trifle glasses with the green stems, the set of cake knives won at a Whist Drive, besides all the items no well-run household should be without (grapefruit knives, a cheese slice) but which are never actually required. It is a museum, this cupboard, to a theory of domestic economy. But it is also a shrine. For somewhere among the packets of doilies and cake frills, the EPNS salad servers, the packets of spills in violent colours, the whist scoring cards and the enema in its black box, somewhere among all this is the box with Uncle Clarence’s Victory Medal, ‘which,’ the citation says, ‘would have been conferred on C/7044 Pte C.E. Peel, had he lived’. The letter is dated Winchester, 10 May 1921. ‘In forwarding the Decoration I am commanded by the King to assure you of His Majesty’s high appreciation of the services rendered.’ Even as a small child rooting for biscuits, I can see that His Majesty’s high appreciation doesn’t amount to much.

Besides, what His Majesty’s high appreciation doesn’t run to, cannot be expected to run to, is that Uncle Clarence has been ruptured. So while everyone who dies in this war dies needlessly, Uncle Clarence dies more needlessly than most. My mother always says he should not have gone at all. I do not quite know what ‘being ruptured’ means. Some shame attaches to it, I know, because Mr Dixon, who takes Standard 5 at Armley National, where I go to school, is ruptured and all the boys think it is a joke. Mr Dixon is the first male teacher I have come up against, he is short and fat and said to wear a truss. What a truss is I don’t know either, but think of it as a device to stop your balls popping out. I find it difficult to connect – still less reconcile – someone as noble as Uncle Clarence and a condition that is both shameful and comical and affects such as Mr Dixon, and maybe I pity Uncle Clarence less for his early death than for his earlier rupture. Though, as my mother says, the one should have prevented the other because in this condition he cannot enlist. With the risk attaching to any surgical operation at this time, he is under no obligation to have the rupture treated, so for a year or two the matter is left and he goes on living at home with his sisters. But in the third year of the war he finds himself jeered at in the street, taunted by girls from the munitions works, and so goes into St James’s, has the operation and in due course enlists. And here he sits in the photograph, just three months before his death, a whole man again.

In the photograph he is wearing puttees. At what point private soldiers ceased to wear these long bandages wrapped round their legs I don’t know. It is certainly gaiters by 1939, ‘anklets webbing khaki, pairs two’ when I am called up in 1952. But the puttee survives (along with many of the attitudes that go with it). In that stagnant military backwater the Army Cadet Corps. No school I ever attend runs to one, but in the short time we are in Guildford my brother is a pupil at the grammar school there and in a uniform identical to that of Uncle Clarence goes on manoeuvres at Pirbright. I watch him as he winds off these muddy brown bandages to find his legs ridged like those of the common house fly, pictured ten thousand times life-size in the Childrens’ Encyclopedia.

I never remember anyone mentioning Uncle Clarence’s grave. There is no photograph of that in the dresser, only a picture of the war memorial tablet in St Mary’s of Bethany, Tong Road. If he has a grave no one visits it. My grandmother never goes abroad, nor do my parents for that matter, and though they think of themselves as women of the world, Aunty Kathleen and Aunty Myra only take to globe-trotting late in life. So, knowing only that he had died at Ypres in 1917, in March 1986 I write to the War Graves Commission at Maidenhead, curious to know if he is just a name on a monument or whether he enjoys the luxury of a grave. It turns out to be more than one and less than the other. For the records say that though he is commemorated by a special memorial in Larchwood (Railway Cuttings) Cemetery and is thought to lie within that cemetery, the exact location of his body is lost. So now it is a wet Friday morning and we have come over on the hovercraft and are driving through St Omer and north to Zillebeke, a village south-east of Ypres, or, since we have now crossed the Belgian frontier, Ieper.

The guidebook says there were three battles at Ypres. The first, in 1914, ended in stalemate and marked the beginning of trench warfare. The second, in 1915, saw the first use of gas. The Blue Guide calls the third battle in 1917 ‘tragic and barren’, as if that distinguished it from the previous two. The ground gained or lost in each case amounted to a few kilometres. The dead, not noted in the Blue Guide, amounted to a quarter of a million.

So now the cemeteries are everywhere, some one hundred and seventy in this salient alone, neat and regular, with their gates and walls and entrances like Roman camps, much neater and more orderly than the suburbs and factory farms they now find themselves among, as if the dead are here to garrison the living: with the countryside not caring, though the place-names aren’t hazed over at all, and each location is immaculately signposted. The cemeteries are so thick on the ground that we can’t find Larchwood and eventually end up down a cul-de-sac at Hill 60, the slight vantage-point south of the town that changed hands many times during the fighting. Now it’s a bare muddy common with a stone telling its history and a memorial to the dead left entombed in its burrows. There is a carpark and a home-made museum-cum-café with vases made out of shell cases and a pin-table. Bungalows back onto the common, with garden sheds. One has a carport and a Peugeot in the drive. Rustic wooden seats denote this desolate place a picnic area, though nothing much grows, grass the permanent casualty, the ground as brown and bare as an end-of-the-season goalmouth. Was it for this the clay grew tall, the plastic flowers in the picture windows, the fishman with his van and a boy riding over the ancient humps of trenches on his BMX bike? Well, yes, I suppose it was.

Unable still to find our cemetery, we give it up and drive back into Ypres and eat a waffle in a chocolate shop, where plump businessmen dally with the proprietress while choosing pralines for the weekend. They go back to the office, tiny boxes of chocolates dangling from one finger, while we drive out on the Menin Road in the rain. Eventually we spot the tip of a cross across a sloping field. There is a railway and there are trees which may be larches and here is the signpost, broken off by a tractor and lying in the ditch.

The cemetery is over a crossing on the far side of a single-track railway. There is a gate, a long finger of lawn alongside the railway, another gate and the burial ground proper: Uncle Clarence’s stone, the stone which is not his grave, is in a row backing onto the railway.

Known to be buried in this cemetery

C7/044

Rifleman C.E. Peel.

King’s Royal Rifle Corps.

21 October 1917

†

Their Glory Shall not be Blotted Out.

To one side is a Gunner Hucklesby of the Royal Field Artillery, to the other a Private Oliver of the Hampshires. It is like seeing who is in the next bed in a barrack room. Many of the names are from Leeds: a Pte Smallwood, a Pte Seed from Kirkstall Road, some with family details, some not. Uncle Clarence’s not. A Second-Lieutenant Broderick from Farnley, at 35 too old for the war, like Crouchback. Another uncle. Sergeant Fortune, a character out of Hardy. Pte Ruckledge of the Wellingtons, Pte Leaversedge of the Yorkshires: rugged names, which, had their owners been spared, one feels the years might have smoothed out to end up Rutledge and Liversedge. Many Canadians ‘known only to God’.

The low walls are sharp and new-looking, unblurred by creeper. There is no lichen on the gravestones, the dead seeming not to have fertilised the ground so much as sterilised it. This is April and too soon to mow, yet the grass is neat and shorn. Standard at the entrance to each graveyard is a small cupboard in the wall, the door of bronze. In it is lodged the register of graves in this and adjacent cemeteries. Larchwood is a modest example with only some three hundred graves. The register begins by describing the history of the place: ‘On the NE side of the railway line to Menin, between the hamlets of Verbrandenmolen and Zwarvelden was a small plantation of larches, and a cemetery was made at the north end of this wood. It was begun in April 1915 and used by troops holding this sector until April 1918.’ The tone is simple, almost epic. It might be a translation from Livy, the troops any troops in any war. There is a plan of the graves, drawn up like an order of battle, these soldiers laid in the earth still in military formation, with the graves set in files and groups and at slight angles to one another, as if they were companies waiting for some last advance. All face east, the direction of the enemy and only incidentally of God.

I sit in the little brick pavilion looking at this register. The book is neat (so much is neat now when nothing was neat then); it is unfingermarked, not even dog-eared. It might be drawn from the Bodleian Library, not from a cupboard in a wall in the middle of a field. Of course, if this foreign field were for ever England, the bronze door would long since have been wrenched off, the gates nicked, ‘Skins’ and ‘Chelsea’ sprayed over all. The notion of a register so freely available would in England seem ingenuous nonsense. I sit there, wondering about this, never knowing if our barbarism denotes vigour or decay. Across the hedgeless fields are the rebuilt towers of Ypres, looking, behind a line of willows, oddly like Oxford. At which point, with a heavy symbolism that in a film would elicit a sophisticated groan, a Mirage jet scorches low over the fields.

For all the dead who lie here and the filthy, futile deaths they died, it is still hard to suppress a twinge of imperial pride, partly to be put down to the design of these silent cities: the work of Blomfield, Baker and Lutyens, the last architects of Empire. The other feeling, less ambiguous here than it would be in a cemetery of the Second War, is anger. Nobody could say now why these men died. The phrase ‘Their glory shall not be blotted out’ was a contribution by Kipling, who served on the War Graves Commission. This is the Friday after the Libyan venture and to assert that there is anything under the sun that will not be blotted out seems quite hopeful. We instinctively think of the conflict between East and West on the model of the Second War, the one with a purpose. The instructive parallel is with the First.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.