It should now be generally agreed except possibly in the Fens that Evelyn Waugh was the greatest English novelist of his generation. Certainly Graham Greene, Henry Green and Angus Wilson thought so, although they and not he won the worldly honours Waugh would dearly have loved. On the other hand, that redoubtable holder of the Order of Merit, J.B. Priestley, did not think so. But then whom would he have nominated? Orwell, Elizabeth Bowen, Ivy Compton-Burnett? Or conceivably ... himself? Waugh has even proved exportable to America: Brideshead Revisited was the most popular series ever shown on American public-service television. Still, his former admirer Edmund Wilson was revolted by that book, and American intellectuals have never put him beside Faulkner, Hemingway or Scott Fitzgerald. And on the Continent there is no translation of Waugh as audacious as Avanti Jeeves.

And yet even those who praise him nearly always begin by dissociating themselves from what they regard as his bigotry, his snobbery, his cruelty, his infatuation with the English aristocracy, his contempt for all other classes, and his pleasure in reaction. But then, so John Bayley observed, they move an amendment. In order to explain these aberrations, they explain that Waugh was a disillusioned romantic. Graham Greene wrote that ‘he is a romantic in the sense of having a dream which failed him’: his first marriage, the war, even in the end his Church, turn out to be illusions. So instead of becoming an English Montherlant he falls in love with the people he formerly satirised, thinks his country is being regenerated and then betrayed during the war, and is so reactionary a Catholic that an Irishman, Conor Cruise O’Brien, denounces him.

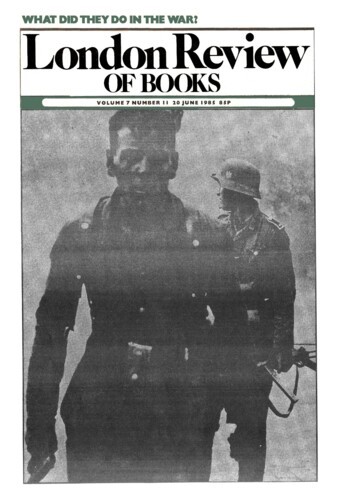

Indeed, the whole of his oeuvre has been read as an attempt to bolster his self-confidence. His critics declare that he wanted to be sure that he really was in with the upper classes and not, like Paul Pennyfeather at the end of Decline and Fall, once more drinking cocoa with Stubbs and listening to a paper on the Polish plebiscites; that everyone had stopped mocking him as a cuckold after his first wife had left him; that he was not, like so many of his fellow writers, an embusqué in some ministry or on some magazine, but an officer and a hero. Yet by the end of the war he knew it was not so. ‘It is pleasant,’ he wrote in 1945, ‘to end the war in plain clothes writing. I remember at the start of it writing to Frank Pakenham that its value to us would be to show us finally that we are not men of action. I took longer than him to learn it.’ Was this what led him to romanticise failure – the failure of Charles Ryder to get religion or to get Julia, the failure of Guy Crouchback to make his fellow officers see what the war was really about?

What is it, then, that makes Waugh a deviant in the history of our culture? Not, surely, that he was a man of the Right, an apologist for Mussolini and Franco. In the Thirties the majority of conservatives preferred them to Stalin; and recent events in Ethiopia make Waugh’s account of that country somewhat nearer the truth than the version of those who took what he said as an apology for Fascism. Nor even that he despised parliamentary politics. After all, the generation before his – Proust, Mann, Joyce, Lawrence, Yeats, Shaw and T.S. Eliot – despised democracy. Nor was Catholicism the mark of a deviant at a time when Belloc urged with some success that it was fashionable to convert to Rome. What made Waugh a deviant was not that he became a Catholic but that he became an Augustinian Catholic.

Orthodox Catholics by definition receive all the tenets of their faith, but even the saints betray their predilection for some part of it which each according to his temperament emphasises as supremely important. The clue to Waugh’s predilection is to be found in Decline and Fall, written before his conversion, where Mr Prendergast confesses to a very special doubt: ‘You see it wasn’t the ordinary sort of doubt about Cain’s wife, or the Old Testament miracles or the Consecration of Archbishop Parker ... No, it was something deeper than that. I couldn’t understand why God had made the world at all.’

Catholicism explained to Waugh why the world was as evil and horrible as it was. Catholicism explained the vile bodies in it. It also explained to him why he was evil and so often cruel and odious. Such questions still trouble us today. We have no difficulty in finding explanations why the world is so full of evil. We are less ready to find reasons why we ourselves are so disagreeable, so prone to rage, so full of conceit and self-gratification, so envious of other people’s success and happiness, so willing to cause unhappiness in order to give ourselves pleasure. Still, we manage to find reasons, and when things get bad the analyst is at hand. Most of us admit that, though we do not always act as we should, we have nevertheless a free will and by exercising it we can and should behave better, or, if that sounds too parsonical, live a more fulfilled or rewarding life.

Of course we know that there are limits to our powers. We are born with a certain temperament, and that temperament in turn is modified, by no means always for the better, by our upbringing and circumstances. If we try to change ourselves and bring our worse defects more under control, retribution follows. In so doing we lose some of our more attractive attributes such as spontaneity, gaiety, generosity. Indeed, the search for behavioural laws which explain the personality in terms of the unconscious, of instinctual drives and of social determinants comforts our generation because they eliminate personal responsibility, always a disagreeable and embarrassing attribute. And yet human behaviour cannot be described solely in terms of impulses, drives and delusions. There are those who believe that mankind is powerless and held in the remorseless grasp of the impersonal forces of history, economics and geography. But even such determinists accept some personal responsibility in day-to-day life. We know that we can to some extent control our actions. Infants learn to control the most primary actions of weeping, drinking and excretion, and in so doing the will plays its part. But why, if we are free, do we so often choose to do evil?

From earliest times men have tried to explain why this is so. One explanation is perennial. The Psalmist was among the first to use it. ‘It is he that hath made us and not we ourselves,’ runs part of a verse of the Old Hundredth (the name Waugh gave to one of his fictional night-clubs). Edward FitzGerald chose that verse for his tombstone, well-remembering the 12th-century verse he had translated from the Persian: ‘We are helpless: thou hast made us what we are.’ Henry VI wrote a prayer: Domine Jesu, qui me creasti, redimsti et preordinaste ad hoc quod sum: fac de me secundam voluntatem tuam ... Why, if God creates us and does with us what he wills – that is to say, predestines us to be what we are – why are we so evil?

No doctor of the Church gave a more authoritative and exhaustive answer to that question than St Augustine. In his great dispute with Pelagius he argued that the Pelagian doctrine of free will was just such as might be expected to have come from a monk ill-acquainted with the world. Pelagius put forward a liberal, common-sense view of free will. To Pelagius the world of nature was good because God had created it. Children were born good but generations of sinful parents made it very difficult for them not to sin. Yet anyone could, if only he made use of the free will God had given him, do good rather than evil.

Augustine was convinced by his own experience that this was wrong. Anyone will understand his quandary who has enjoyed being young and wanted to get on in the world as much as Augustine did, when he was making his name as a dazzling rhetorician and keeping an attractive mistress. Anyone who has known temptation knows that the will is not the simple faculty Pelagius thought it was. It can hold contradictory impulses simultaneously. The mind, said Augustine, commands the body and the body obeys. But when the mind tries to command itself, it often meets with resistance or open rebellion. In that famous sentence in the Confessions Augustine recalled his youth and his prayer to God. ‘But I was very miserable when I was young, wretched at the beginning of my youth, and I asked you to make me chaste and I said: give me chastity and continence but don’t give me them yet.’ So Augustine concluded that no one can stop sinning simply because he wants to do so. It is only God’s grace, and his grace alone, which prevents a man from sinning. Nothing he did himself could help. His will alone was powerless, and hence he could not claim any merit if he did not do wrong. This was the real meaning of original sin.

Augustine lived in an age which had seen the collapse of civilisation in the ancient world as men had known it for four centuries. To him and his contemporaries the collapse must have been caused by the triumph of evil. The Neoplatonists produced the ingenious but unconvincing explanation that evil belonged to the world of non-being. The Manichees declared that there were two worlds, the world of light created by God and the world of darkness created by the devil. Augustine himself became a Manichee for 11 years because he was disturbed by the existence of evil in a world made by God. Only gradually did he come to believe that God created everything and it was sin which created evil. Evil meant the deprivation of God and the Good, and the world was infected throughout with evil.

Augustine then went on to explain man’s relation to society and the state. There were two cities, he said: the city of this world and the city of God. The city of man was not wholly evil because God had created it. The Church was of it, Christian emperors ruled it, and men had duties of civil obedience to the emperor. But it was not the business of the state to realise justice. Only the city of God could be a just state. A Christian state was better than a pagan state, and only the Church could unite true believers: salus extra ecclesiam nonest. But both were founded on aggression, oppression and greed. Earthly power on earth changes hands. So far from the sack of Rome by Alaric being a portent, so far from its being a punishment on the Empire for becoming Christian, it was merely one of hundreds of examples of changes in fortune which seem momentous to those alive but are insignificant in the eyes of God or when set against the history of the world.

There is a terrible chapter (Six in Book Nine of The City of God) where Augustine considers the plight of a judge. A judge in attempting to discover the truth of a crime may put a man to torture. What if the man dies under torture; or, unable to bear the pain, confesses to the crime though he is innocent? And what of his accusers? They may sincerely have wished to bring criminals to justice, yet if they cannot prove the truth of their accusations, the judge will feel himself compelled to put them to torture for bearing false witness. In doing these acts, does the judge commit a sin? Unless he acts through malice, he does not. He does these things because ‘his ignorance compels him.’ He should recognise ‘the misery of these necessities’; all he can do is to plead with God to deliver him from such dilemmas. Like the judge, we must do the best we can, but no one should for an instant delude himself that he can execute justice or understand the depths of human responsibility or action.

Waugh dismissed politics no less equivocally:

I believe that man is, by nature, an exile ... that his chances of happiness and virtue ... generally speaking, are not much affected by the political and economic conditions in which he lives. I believe ... that there is no form of government ordained from God as being better than any other; that the anarchic elements in society are so strong that it is a whole-time task to keep the peace. I believe the inequalities of wealth and position are inevitable and that it is therefore meaningless to discuss the advantages of their elimination; that men naturally arrange themselves in a system of classes; that such a system is necessary for any form of co-operative work ... I believe that Art is a natural function of man; it so happens that most of the greatest art has appeared under systems of tyranny, but I do not think it has a connection with any particular system, least of all with representative government, as nowadays in England, America and France it seems popular to believe.

On such grounds Waugh accounted for the decline of Britain and the decay of her empire in Augustinian terms. The whole world was so sunk in original sin that by no act of their own will could men change things for the better. Progressives, reformers, liberals and socialists were particularly impious because they were attempting to realise the city of God on earth. Even righteous wars were futile: Augustine said that victories bring death with them or are doomed to death. That is why Waugh’s trilogy, ‘Sword of Honour’, proclaims the triumph of dishonour and the betrayal of such ideals as its hero had when he joined the Army.

When Waugh in his novels creates heroes, they are virtuous simple men like Tony Last and Guy Crouchback, doomed to be victims. When he creates rogues and scoundrels, they hit the jackpot. No wonder: for Satan is a Prince in this world and Augustine taught us that man should not put his faith in governments, soldiers or judges. He should welcome calamity as a reminder to keep his eyes fixed on the Eternal City of God. ‘Opt out’ is the moral. ‘These characters,’ wrote Waugh in the dedication of Put out more flags, ‘lived delightfully in holes and corners and have been disturbed in their habits by the rough intrusion of history.’ The quietist and cynic will make more of life and do less harm than the progressive who fabricates futile plans for international peace and the elimination of poverty. Of course there must be no truck with pagan religions such as Communism, but Catholics should not delude themselves that the spread of Communism is worth a crusade. In the eyes of God it was a temporary aberration, like Nazism, or the Reformation – another instance of man’s perennial iniquity and God’s amazing grace.

As an Augustinian. Waugh was a contrast to the previous generation of Catholic apologists. The neo-Thomists had wanted to show how rational Catholicism was. The modernists such as Von Hügel or Loisy wanted to show how humane and in tune with historical scholarship it was. Per contra, Waugh thought how sensible St Bernard had been in dealing with presumptuous intellectuals such as Abelard. In the last sentences of Decline and Fall there is a reference to the Ebionites – a sect of poor Jewish-Christians who rejected the Pauline Epistles and thought that Jesus was the human son of Joseph and Mary until his baptism, when the Holy Spirit lighted on him. The passage reads: ‘So the ascetic Ebionites used to turn towards Jerusalem when they prayed. Paul made a note of it. Quite right to suppress them.’

He had even less use for Chesterton’s eccentric socialism and empathy with the poor. Waugh did not consider Catholicism to be a religion of joy and ebullience encompassing all man’s activities, the tavern and the country fair. He had more in common with Belloc: the same delight in bigotry, and towards the end of his life the same misanthropy. There was in him an anti-Dreyfusard streak, though it was not as virulent as Belloc’s disgusting anti-semitism. But that curious republicanism in Belloc, his delight in Danton and the French Revolution and his assumption that France was the centre of civilisation, was as strange to Waugh as Belloc’s lack of interest in the theology of the Catholic faith. To Waugh, theology, the liturgy, the four last things and the most terrible images of the Christian faith were constantly before his eyes: he refers to them time and again in his letters. Christopher Sykes teased Waugh once by suggesting that Hell must be his favourite dogma. ‘If,’ he replied, ‘we were allowed “favourite dogmas” it might be. If you mean I see nothing to doubt in it and no cause for “modernist” squeamish revulsion, you are quite right.’

Someone may wonder of so strong an Augustinian why he did not remain a Protestant. Classic Protestantism did indeed explain how sinful man could be redeemed by God’s grace and stressed that salvation lay in faith, not in good works. Luther appealed to Augustine’s authority. But although Protestants make allowances for backsliders, they have always been inclined to believe that the converted were expected to lead a changed life: the change was evidence for the conversion. Waugh never expected to change his nature. He needed to be convinced that if he continued to commit the seven deadly sins he could be saved so long as he submitted to the Church, confessed, and was sustained by her sacraments. Commit the seven deadly sins after conversion he certainly did. Most prone to envy, gluttony and anger, far from sound on pride and covetousness, and at the end of his life more and more a prey to accidie, or the melancholy that springs from boredom and dissatisfaction with life. The only sin he mastered was lust. When Nancy Mitford up-braided him for his cruelty to some young man who tried only to express his admiration he replied: ‘You have no idea how much nastier I would be if I was not a Catholic. Without supernatural aid I would hardly be a human being.’ He asked Cyril Connolly never again to invite him to meet Dylan Thomas. ‘He’s exactly what I would have been if I had not been a Catholic.’ He would ask his friends how it was possible for him to deny the existence of evil in the world when there was so much evil in himself. His self-hatred was deadly. He never once hinted that he was brave, generous in private, and loyal to friends. What more disobliging self-portrait has any writer left than that in the first chapter of The Ordeal of Gilbert Pinfold?

In fact, people have always in one respect considered him to be a deviant. He belonged to a generation many of whom considered class divisions to be a blot on our national life, and who consequently resented those who used the old social barriers as a fortress from which to attack the new enemy of Hoopers and do-gooders. Nor were they wrong about Waugh’s relations with his social inferiors. The bullying, sardonic, insulting manner he adopted was appalling. It was this that made him in the Army, as Bob Laycock put it, ‘so unpopular as to be unemployable’. He bullied with diabolic cleverness, so his biographer said, picking on the weak and defenceless, putting those ill at ease even iller, probing for the social failing or lack of security. When Laycock decided after all to risk taking him with his commando for the landings in Sicily, his Brigade Major said to him: ‘You will regret it, Brigadier. Evelyn’s appointment will weaken the Brigade as a coherent fighting-force. And apart from anything else, Evelyn will probably get shot.’ ‘That’s a chance we all have to take.’ ‘Oh, I don’t mean by the enemy’.

What people resent, however, is not Waugh’s portrayal of the Hoopers and Trimmers. They resent what they regard as his infatuation with the upper classes. Ever since J.B. Priestley, after reading A Handful of Dust, gave him the patronising advice to ‘leave the world of society light-weights’, critics have lamented his snobbery. Wodehouse never asked us to take the Drones Club seriously. Why then should we admire the members of Brats? Many critics consider – and I think they are right – that during the war Evelyn Waugh let his guard drop. The closing sentences of Put out more flags refer to the time when in 1940 Britain alone was left opposing Nazi Germany and her accomplice in the partition of Poland, Soviet Russia. It is then that the old buffer Sir Joseph Mainwaring said: ‘ “There’s a new spirit abroad. I see it on every side.” And poor booby, he was bang right,’ added Waugh. In 1941 he found to his fury that we were fighting on the same side as Stalin and his commissars. It was only later, after Brideshead, that he recovered his Augustinian balance, and the war became an unheroic episode in which even a most elegant upper-class crony is shown in the war trilogy to be a coward under fire. In Brideshead Revisited he romanticised the Flyte family – though, it is worth pointing out, none of the individual Flytes. But he does not ask himself why he is dazzled by them. Pansy Lamb told Waugh that when she looked back on her debutante days of going to balls in historic houses, she recollected that

most of the girls were drab and dowdy and the men even more so ... Nobody was brilliant, beautiful ... most were respectable, well to do, narrow-minded with ideals in no way differing from Hooper’s except that their basic ration was larger. Hooperism is only the transcription in cheaper terms of the upper class outlook of the 1920s and like most mass productions is not flattering to its originators.

Yet in fact Waugh understood these matters all too well. He simply didn’t have the stamina of the dedicated sycophantic snob. ‘Yes,’ he said of one aristocrat of the highest lineage, ‘Yes, I used to know him with the Lygons. But he’s dull, so dull. And you can imagine how much I wanted to like him.’ As his biographer says, true snobbery is made of sterner stuff. Indeed it is the ancient aristocracy themselves who are the most hardened snobs. Their favourite topic of conversation is kinship in its most simple anthropological form of who married whom. Waugh was not quite at his ease with the old straight-forward nobility. Nor they with him. They summed him up accurately as a dangerous arriviste. He was not invited to Hatfield, Houghton, Hardwick or Holkham. His intimate friends were déclassé aristocrats: Lady Diana Duff Cooper, Nancy Mitford, Ann Fleming, spirited women who had broken out of the suffocating embrace of eligible matches and estates. His clothes were sometimes a comical caricature of what a country gentleman and former officer of the Blues would wear.

The Augustinian conception of grace shone through his writings. If a man was brave, spontaneous, generous and ardent, if he was open and ready to accept life, or held charitable views about others, or if he did good to others, especially to the poor or to those ill at ease, there was no merit in it. He was not the better for so doing. Whatever good he did was due to God’s grace alone and it was presumptuous to praise him at all. Someone suggested that his friends, who were so agreeable, loyal and charming, needed only a divine spark to perfect them. The old Augustinian spoke: ‘They were aboriginally corrupt,’ wrote Waugh. ‘Their tiny relative advantages of intelligence, taste, good looks and good manners are quite insignificant.’

At the end of Decline and Fall Peter Beste-Chetwynde staggers into Paul’s room at Scone College, tipsy after the frolics of the Bollinger. ‘You know, Paul, I think it was a mistake you ever got mixed up with us; don’t you? We’re different somehow. Don’t quite know how. Don’t think that’s rude, do you, Paul?’ Waugh knew in his heart he was different. When his muse spoke to him in 1943 and he knew he must get Brideshead down on paper, he did not hesitate to pull every string to get three months’ leave. One of those strings was pulled by Brendan Bracken, then Minister of Information, a Conservative who would have found himself at home in Mrs Thatcher’s Cabinet. This did not inhibit Waugh from drawing in Rex Mottram the portrait of an adventurer who has all the smooth techniques of power learnt in Fleet Street and all the worship of success learnt in the City.

He might, however, have been expected to get on with Duff Cooper. But no: at the Embassy in Paris he needled him by insisting that when Duff Cooper had been Minister of Information at the time when Hitler invaded Soviet Russia, his indiscriminate praise of the Soviet Union had been one of the factors which had led to the return of the Labour Government in 1945. Suddenly Duff Cooper turned purple and yelled at him, ‘It’s rotten little rats like you who have brought about the downfall of the country’ – and then accused him of homosexuality, cowardice and pacifism. And yet ludicrous as the charges were, Duff Cooper sensed that Waugh was a déraciné of the Twenties and not like himself, a Guardee of the First World War who had fought in the trenches. Waugh was a malignant tease who, unlike others who had commanded troops, refused to become a responsible leader taking his place in the Establishment. To Duff Cooper, Churchill had been the architect of victory, to Waugh – who never allowed awkward facts such as the decline of British military and political power in relation to America and Russia to affect his views – to Waugh, Churchill, with his deluded tolerance of Uncle Joe and of anti-Catholic totalitarians such as Tito, betrayed all that the war should have been fought for.

He admired the self-assurance of the upper classes. All his most lively characters glow with this self-assurance: among them the slum evacuees, the terrible Connolly children. But he himself did not always have self-assurance. Cyril Connolly found him, when they were undergraduates, roaring drunk outside Balliol and asked him why he was making such a noise. ‘I have to make a noise because I am poor.’ he said. The success of his books brought him self-assurance and the entrée to London Society. But he remained different. Anyone as aware of his own failings could hardly be expected to be indulgent to the failings of others. He had only to glance at someone and his eye travelled down to that person’s feet of clay. We all have feet of clay. Yet part of the agreeable hypocrisy of life, indeed what makes social gatherings supportable, is that we glance away when we see our friends’ feet of clay. Waugh would not join in the hypocrisy.

No doubt Carabosse had been in at his birth. Muttering her spells, she cursed the child with the temperament of a bully and the restless spirit of a frondeur. But the good fairies gave him a will of iron, so that, although he was unable to take discipline from anyone but himself and spire struggled with rage for the mastery, he turned even his bad gifts to account and, artist as he was, brought them under control.

Waugh was a deviant because he refused to come to terms with the post-war consensus. By ‘consensus’ I mean the alliance struck between the upper-class Tories of his generation and the Gaitskellite intelligentsia. Both accepted neo-Keynesianism and full employment; both wanted through political action to diminish class and racial antagonisms; both accepted the trade unions as partners and hence accepted inflation; both put faith in the ability of social scientists to solve social problems; both turned to utilitarian ethics, believed in the importance of fundamental scientific research as the prerequisite of industrial growth, and were sceptical about deference and pre-war sexual prohibitions and censorship. In fact, both were opposed to the culture of the old pre-war Establishment. To Waugh all this was anathema. He was too intelligent not to know that his views on politics were absurd. But for him the welfare state was the Trojan horse of Communism. He despised Conservatives as much as Liberals.

But worse was to happen. He lived to see the beginning of the renewal movement within the Catholic Church, the injunction to celebrate the Mass in the vernacular in atrocious translation, the simplification of the Liturgy, the new emphasis on sermons, the call to the faithful to sustain people in the Third World. He hated the Ecumenical movement. When he was visiting Jerusalem his cicerone, a Franciscan monk, told him that at half an hour before midnight on Easter Eve clappers are sounded to awaken the Greek and Armenian clergy who are the first to begin their offices at the Holy Sepulchre. ‘I see,’ said Waugh: ‘11.30 p.m. Heretics and Schismatics woken up. What next?’ ‘Oh Mr Waugh, we look on them as our brothers in Christ,’ said the monk. He did not. This was a far cry from the delectable day in 1950 when Pius XII issued an encyclical declaring that the assumption of the BVM was now an article of faith. That act had delighted Waugh. His only regret was that the Pope had not gone further and elevated the BVM to the position of co-redemptress with Christ of the human race. He needed his life sunk in despair, a deviant – though not an apostate – from the way his Church was developing.

And yet he had one incomparable advantage as a writer. He operated from an impregnable base. You may find it repulsive, but it is self-consistent. You may find it implausible, but so was Tolstoy’s conception of war. He is not only a better writer than Graham Greene: his vision of life is more consistent. Greene is always trying to explain how his religion may not be so inflexible and severe as it at first appears. The adulterer, the suicide, the whisky priest, and finally – which so pained Waugh – ‘the settled and easy atheism’ of Querry, are all to be understood as in some way susceptible to, and even visited by, God’s grace. We do not ourselves have to be Augustinians to acknowledge that the vision of the world which Waugh preferred was far more powerful, convincing and intense. His novels therefore possess a devastating consistency. There he stands mocking everything his contemporaries believed in. The mockery hits the mark.

His gift for mockery saved him from total hatred of the world. So did his belief in the value of beauty. (The word ‘beauty’ is appropriate: Waugh was an aesthete in art.) They were also symbols of man’s need to have roots in the past. Like Lawrence, he wrote unforgettable passages protesting against the transformation of rural England into ribbon development, arterial roads, factories, disused canals and bungalows. But he had nothing in common with many of those today who protest at the evils of society.

On two counts Waugh did not deviate from his generation. He shared the assumption common to many of them that public life, business, money-making, are despicable occupations. And he also saw life as a comedy. The forbears of his generation – Wilde, Shaw, Beerbohm, Saki, Firbank, Strachey. Wode-house – bred at Oxford a collection of wits some of whose humour has perished since it found no other form than conversation. This was the generation of Bowra, Betjeman, Harold Acton, John Sutro, Connolly, Powell and Alan Pryce-Jones. Waugh was the supreme master and his novels are fit to stand by The Importance of Being Earnest. His vision is so penetrating and fantastical that infidels, heretics and schismatics, as well as the orthodox, can inhabit that world and rock with laughter. They do so at their peril. For as they comfort themselves by saying that Waugh’s vision is deliberately absurd and his ideals archaic, as they denounce his cruelty and profess themselves revolted by his snobbery, the integrity and inner coherence of this Augustinian view of life should compel them to reflect whether the different – of course infinitely more civilised – ideals they hold are all that better at explaining why our society takes the course it does, and why people still behave in ways which are either disgusting or calamitous. The young critic Rupert Christiansen chose two good epithets to pinpoint his humour – blistering and terrifying. In ghost stories the teller of the tale is sometimes described as becoming aware that he is being observed by an invisible but hostile presence. So the reader of Waugh’s novels as the smile fades from his face may well be unable to control a shudder. No wonder Hilaire Belloc, when he first met this new young Catholic writer and looked at those blazing eyes, arched eyebrows and pitiless gaze, muttered to himself: ‘He is possessed.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.