Some of the stories in Secret Villages were published in the New Yorker, some in Encounter and some in Punch. It is interesting to compare the three styles. Those for the Americans make Scotland seem a wee bit exotic, romantic, with an unobtrusive sprinkling of factual information, as if a local were explaining to the tourists, the summer people. For Punch readers it is assumed that Scotland is already pretty familiar, and the stories may have a punch-line. The Encounter stories are more allusive, elliptical, up-market.

The first two stories concern illegitimate bairns. One is called ‘South America’: a Scottish engineer goes to that continent, leaving his wife with two children, and seems disinclined to return, what with the war and everything, and she bears two more children to other fathers, settling down with a schoolmistress friend to make a sort of family. We may fancy that we know how other Scots women would respond to such behaviour in a small town. In fact, there is a ‘here-where’ poem by G.S. Fraser discussing the response:

Here, where the women wear dark shawls and mutter

A hasty word as other women pass,

Telling the secret, telling, clucking and tutting,

Sighing or saying that it served her right,

The bitch!

However, Douglas Dunn’s heroine persuades the other women to laugh with her, and the lawyer men are taken with ‘her rugged aplomb’. This story was for the New Yorker.

The second story, ‘Twin Sets and Pickle Forks’, is about a Scottish tea-room run by Miss Frame, with two bonny waitresses called Maureen and Mandy, since Miss Frame holds that ‘middle-aged men like to be served by attractive girls.’ Mandy suggests that ‘we should ask Mr Cruikshank out an’ gie’m the scare o’ ‘is life. Is that no’ an idea, Miss Frame? We’d rub ’is body wi’ meringues an’ then clear off wi’ that black suit o’ his.’ But Miss Frame responds: ‘That’s enough of that, m’lady.’ She is rather stiff and élitist, allowing only favoured customers to use her silver pickle-fork. But then Miss Frame’s illegitimate son comes to the tea-shop and she is afraid that Maureen and Mandy will tell other women about her secret. They promise not to do so, on condition that she gets rid of the pickle-fork. ‘It’s the pickle-fork that no’ everybody gets to use. It bothers me. An’ that’s ma price. Get rid o’ it.’ As the punch-line suggests, this story was for Punch.

The third story, ‘Wives in the Garden’, was for Encounter. It is about two couples who holiday together on the coast of Kintyre. One of the men is a university lecturer with ‘an amiably long-suffering expression in the face of untenable points of view’. He says things like ‘You sang a similarly sentimental aria last year,’ in normal conversation. We are in a different world, a different village of the heart, as the husbands (in their thirties in the Sixties) contemplate their wives in the garden, remembering the Fifties, when Henrietta called herself ‘Hank’ and tried to look like Juliette Greco in downtown Glasgow. To match ‘Wives in the Garden’, there is another Encounter tale called ‘Women without Gardens’, about lonely old ladies who inspect house-owners’ lilacs and lawnmowers, as if they were judges, during their afternoon walk to the municipal gardens which, being public, they suppose they own.

Douglas Dunn has remarked about his Terry Street poems that he was emulating the know-all poet in Browning’s ‘How it Strikes a Contemporary’:

not so much a spy

As a recording chief inquisitor,

The town’s true master, if the town but knew!

Dunn added: ‘Except that, of course, I wasn’t.’ In Secret Villages he adopts the same pose: a narrator perfectly at home in all regions, among all ranks, understanding everybody – a convention accepted by most storytellers until this century when it began to be rejected as a usurpation of the God’s-eye view.

Elizabeth Jolley, for instance, is quite capable of telling a story but seems to feel that she ought not to. Miss Peabody’s Inheritance is primarily about a headmistress with lesbian tendencies and her affairs with pupils and fellow teachers: but the story is deliberately wrapped around with fictive devices. The headmistress, Miss Thorne, borrows a literary review from a young man on an airplane. ‘Just my sort of reading!’ she says smugly – and then she reads this: ‘The discussion falls on the concept of structuralist reading and the exposure of the artistic process as being an achievement, on semantic levels, of harmonious surfaces built on insoluble conflicts, for example, the lexical, the grammatical and syntactic levels, with an ideological solution to the contradictions in the mode of discourse, the angle of narration and the symbolic structure of a culture ...’ This dismays Miss Thorne, who is ‘unaccustomed to being unable to understand anything she reads’. The reviewer’s article ‘makes her, for a moment, doubt her own position ... She does remember vaguely reading another statement that being a character in a novel is apparently not being a character at all. Such ways of thinking are too much for her.’

The argument is particularly difficult for Miss Thorne, since she is a character in a novel by Diana Hopewell, herself a character in Miss Jolley’s novel. Diana Hopewell lives in Australia and sends instalments of her novel to her fan in England, Miss Peabody, who has a rather boring office job and a crotchety old mother to look after. Miss Peabody finds the novel quite exciting – this story of a proud, matronising Thatcher-like woman following the promptings of her heart among rosy-cheeked girls with aprons crackling against bare skin, like an Angela Brazil tale gone mad. Miss Peabody starts getting drunk and embarrassing other London office-workers. When her mother dies she goes to Australia to meet Diana Hopewell, whom she believes to be an Amazonian, horse-riding sort of woman. But the readers (Miss Jolley’s readers, that is) know that Diana Hopewell is really a cripple, under the control of a matron in a dismal private hospital. When Miss Peabody arrives she finds that Diana Hopewell has just died: the faithful reader is left with the novel as her inheritance.

Miss Peabody’s Inheritance is a sad story, despite its perky grin, and Mr Scobie’s Riddle is even more so. This is a fairly straightforward ‘black comedy’, with similar concerns. It is set in an Australian private hospital, where old people are dumped by their young relatives, under the command of a stern matron and two sexy young nurses, aprons crackling against bare skin, who are enjoying a lesbian affair. One of the ‘patients’, Miss Hailey, is an unpublished poet and novelist: she was at school with the matron but cannot win back her friendship. A nurse observes that Miss Hailey finds her attractive, so she entices her to a caravan where the matron can catch them in an illicit embrace. This sort of thing has happened to Miss Hailey before, when she was a schoolmistress – and, curiously enough, it has happened to one of the old men in the hospital, Mr Scobie, who was seduced by a girl pupil when he was giving piano lessons.

The old men in the hospital are more eager to escape than the old women are. The matron will not let them go because she wants them to die in her hospital, after signing away all their property to her. So they must submit to being well washed by the sexy nurses and then put out to dry in the sun, pinned up in shawls. Mr Scobie reads the Bible and William Blake, and then he makes up little riddles. One of them is about dying – but nobody wants to hear about that: it is held to be a tasteless riddle. This is a comedy to make the reader doleful.

Don Bloch, an American, writes about hospitals and medicine without any attempt to be funny. The Modern Common Wind is about leprosy in Kenya and could fairly be advertised as ‘not for the squeamish’. The narrator is supposed to be an African and the publishers congratulate Don Bloch on having ‘caught the authentic voice of gifted African storytellers’. This is putting it rather strong. The author shows no gift for storytelling. What he has caught, as a mannerism, is a characteristic use of English tenses by Africans. His story begins:

Asumani Tiema, that most famous omufumu of the Wangas, was having seven wives. Together they were bearing him seventy sons. Shebani was the first-born ... Tiema was selecting Shebani as his successor not merely because of his being the first-born. Although Shebani did not go to school, everyone could see he was having a good intelligence.

An omufumu in Kenya seems to be what the Nigerians call a babalawo or native herbalist: a European in this novel calls Shebani a ‘witch-doctor’. Shebani seems to be respected in his profession, but there is leprosy, somehow, ‘in his family’, and this disease he cannot handle. At the end of the book he goes to visit the grave of a leprosy victim but is misdirected for some mean reason by another African who despises Shebani’s magic. The novel concludes (and we notice the tenses again): ‘Besides, that man’s magic, how could it be helping, even-when it was true? The place where I was taking them, that is one where nobody has ever been buried.’

The use of auxiliary-verb forms by many different kinds of African indicates, I think, a different way of talking about time in their languages: if so, it is as interesting as the fact that we have no future participle, as the morituri Romans did. I remember a Nigerian girl who wanted a new dress and, when she was told her old dress was pretty good, replied: ‘I cannot be wearing it for Occasions.’ She was obviously translating her thought directly from the Yoruba (‘occasions’ meaning parties, festivals, ceremonies), but Don Bloch’s rather monotonous use of constructions like ‘was having’ or ‘could be helping’ merely sounds like an American imitating an African, in some new, depressing form of minstrel show.

Africans often appear as bold, vigorous, attractive, formidable people in Nigerian writing (and indeed in tales by Rider Haggard and John Buchan), but books from white-settler territory, by such authors as Athol Fugard or J.M. Coetzee, seem to present them as permanently morose, deformed in body and soul, to be pitied from a great height. I exaggerate, but Donald Bloch’s morbid novel supports my exaggeration. The narrator keeps making hyper-critical remarks about ‘we Africans’ with an exclamation-mark. ‘How generous we Africans can be, even with our very strong diseases! Yes, we like to give them away!’ This is a comment on the alleged practice of putting the clothes of a dead person in the river, so that someone else will catch his disease. ‘How slow we are to hear someone calling for help.’ ‘Friends are a difficult thing for Africans.’ ‘Africans have never loved the sight of suffering. In those days no one needed to pretend not to be happy when one died.’ ‘Our African doctors save whom they want to. Some, for a high price, will help you from an enemy too.’ ‘Why do we Wanga laugh when that is the last thing any happy person would do? There are times in life I have thought that laughter is a curse, together with the colour of our skin.’

These miserable little generalisations about ‘Africans’ are the only positive statements about ‘real life’ that I can find in The Modern Common Wind as we follow the careers of lepers and people who fear leprosy in their search for modern or ancient cures. With such subject-matter, one feels a need for a political or medical theory to give some point to this monotonous study of desolation. It is not enough to be told about repulsive African medicines and ill-run European hospitals, missing hands and feet, throats that can be seen through the space where the nose ought to be.

Denis Johnson is another American writer who has attempted a large theme in a novel not-for-the-squeamish. Fiskadoro is about desolate survivors in Florida after a nuclear war. It is rather like a teenager’s ‘fantasy-book’, except that the prose is more obscurely poetic and the storytelling less lucid. Fiskadoro is a Hispanic boy, son of Jimmy Hidalgo, who derives his name from pescador (‘fisherman’) and fisgador (‘harpooner’). He comes to Mr Cheung (part-Chinese, part-English) to learn how to play the clarinet. Mr Cheung is trying to build up an orchestra, but this is difficult since all the people in the neighbourhood are ‘in quarantine’: it seems that the only political system intact is Cuban and, when the quarantine period is over, perhaps the Cubans will come to rescue the survivors. They sometimes hear broadcasts from Cuba on their radio sets. Or perhaps they should pray to some deified pop-music singer, Bob Marley or Jimi Hendrix. Or perhaps voodoo or some other old-time religion would help.

The town where Mr Cheung and Fiskadoro live is called Twicetown, because it was bombed twice: it used to be called Key West. Sometimes they are visited by black men in dreadlocks bringing marijuana: these black men are called Israelites. Even more frightening are the desechados who live in the Florida swamps: they are seriously damaged – ‘hump-backed or armless, or moving carefully in a way that said they were blind or drunkenly in a way that said something was missing in their heads.’ As a result of the nuclear war, they are as disfigured as the lepers in Don Bloch’s novel. Fiskadoro, when he is captured by these people, notices ‘a woman who had no nose, only two large nostrils in the middle of her face’ and another woman ‘who had no arms or hands, only fins like a fish’ and a boy with ‘eyes on either side of his head, almost where his ears were’. Definitely not for the squeamish.

No doubt, the desechados are trying to be kind. They give the captive Fiskadoro food to eat. ‘They took any snake with two heads and instantly ate it alive in order to swallow its strangeness and power ... They tore open big bugs with popping eyes that lived in the water like fish, and held the pale meat in his face, and he cried.’ Let us hope that the squeamish have left us now, because the desechados are about to do something very nasty to Fiskadoro’s penis, to make him ‘like other men’.

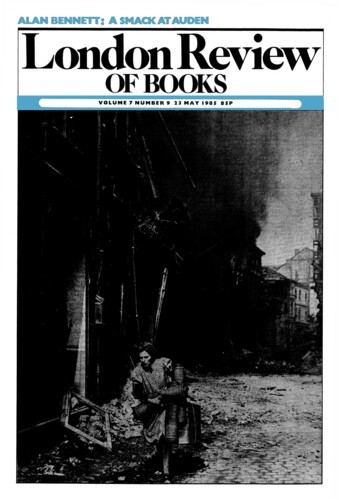

The novel is not entirely about the future, for Mr Cheung has an elderly relative, Mrs Wright, who is 100 years old and can remember the fall of Saigon, ‘the hordes of skeletons dragging the sacks of their skins behind them through the flaming streets, the buildings made out of skulls’. After her reminiscences, it is quite a relief to sail with Mr Cheung to Key Marathon, where someone has acquired a book to read aloud, explaining the survivors’ situation. From the quotations it seems to be a book (perhaps by John Hersey?) about the results of the American bombing of Japan. Mr Cheung feels his nausea dissipating even before they dock at the local slaughterhouse. ‘The slaughterhouse had once been a hotel. The stripped headless carcasses of several dogs and goats were hung from poles laid across the width of the swimming-pool.’

We have come a long way from Douglas Dunn’s tales of Scotland. I feel like a film reviewer who has started the week with an Ealing comedy or one of David Lean’s novel-adaptations (cutting out all the messy, sissy bits) and then has to plough through a set of desperate cast-of-thousands horror-movies. No doubt, Don Bloch and Denis Johnson are properly concerned about leprosy in Africa and the dangers of nuclear war: but piling on the agony is no substitute for storytelling. Let us hope that publishers and reviewers stop calling such books ‘compassionate’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.