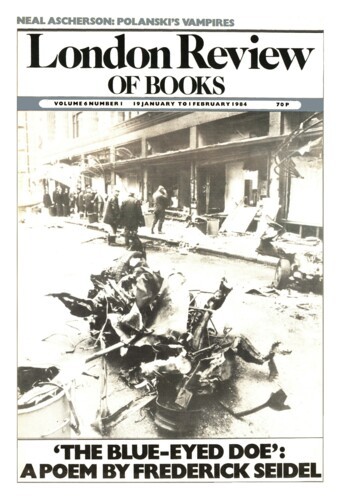

A secret Clan na Gael memorandum exactly a century ago, two years after the inauguration of the 1881 Fenian bombing campaign in London and Liverpool, vowed to ‘carry on an incessant and perpetual warfare with the power of England in public and in secret’. That warfare has been intermittent rather than incessant: but the Christmas bombing in London offers devastating evidence of its durability.

The dynamitards, as the Fenians were known by their frequently frustrated opponents in the intelligence services, were capitalising on a new technology – the invention of high explosives. Their successors have shown themselves to be murderously adept in the same line of business: the car bomb concept has been a significant Irish contribution to the lexicography of international terrorism. Nor do the parallels stop there. Almost a hundred and sixty years ago, a landlord was complaining that ‘the lower orders of the county Leitrim in general are sworn Ribbond men so that my own tenants living on my own property will no longer assist me against them – indeed I should not consider my life safe now amongst them.’ In the week the Harrods bomb went off, members of the same organisation which planted it shot and killed two of their fellow-countrymen, members of the Irish security forces, in the inhospitable Leitrim uplands where they had been holding for ransom a senior executive in a multinational company operating in Ireland.

Some things have changed, of course. The greater part of the island of Ireland is now an independent state. Northern Ireland itself has gone through several sea-changes, from Stormont through the power-sharing Assembly to Westminster direct rule. And yet, no matter how much the political landscape alters, violence remains endemic, like a morbid condition which is triumphantly resistant to all known forms of political antibiotics.

The degree to which the IRA in general, or Mr Gerry Adams in particular, may have been responsible for this or that outrage is largely a matter of theology. It is not just that the IRA – and indeed most similar para-military organisations on either side of the Northern conflict – have a well-known track record of evading responsibility for terrorist attacks that go wrong, or which provoke an unforeseen public reaction. It is also that even in the modern IRA, with almost fifteen years experience of armed conflict and a highly sophisticated command structure, anyone with access to a stick of gelignite is, in the final analysis, his own Chief of Staff. In circumstances like these, responsibility is a movable feast. And the tears shed by Sinn Fein and its politicians about media coverage are largely of the crocodile variety. Listening to an organisation which has developed considerable expertise in media management (not excluding death threats to named journalists) is rather like hearing Herod complain about the annual report of the NSPCC.

Recent television programmes on BBC and ITV, readily accessible to many Irish viewers, have been investigating para-military organisations like the IRA and the INLA, and their political front organisations Sinn Fein and the IRSP, with a toughness and persistence that seems to some observers to mark a distinct shift in emphasis. That shift is away from the temptation to romanticise the men of violence – a temptation given added glamour, it must be said, by some of the more dotty decisions of media bureaucrats in the past – and towards the best public service broadcasting tradition, in which media access can be given to apologists for the indefensible in a context which stops well short of legitimising their cause.

This renewed media interest, which has a political significance in its own right, is also undoubtedly due in part to the changed Sinn Fein tactics, involving more and more frequent incursions into representative politics. It is vitally important to recognise, however, that this development is not a substitute for the armed struggle, but an addition to it. As one of the speakers at the Sinn Fein Ard Fheis (annual conference) put it in Dublin some time ago, they travel ‘with the Armalite in one hand and the ballot box in the other’. More than that, the relationship between their electoral successes and the violent achievements so proudly displayed in the IRA shop window is an essential one. It is certainly true that Sinn Fein, in the North, and to some degree in the South as well (their representative in a recent parliamentary by-election secured 6 per cent of the vote), have now embarked with gusto on a campaign of supposed community service, setting up clinics and advice centres to assist the citizenry with their housing applications, benefit claims, and all the other paraphernalia of the modern welfare state. Quite apart from the obvious cynicism of such an exercise, the importance of the link between this activity and the murders and explosions should not be underestimated. Intimidation takes many forms, and the IRA’s reputation for effectiveness is only partly based on mythology: its known record for dealing brutally with backsliders and informers in its own ranks is a powerful calling card. This development to some extent belies Dr Townshend’s contention that political violence in Ireland ‘is used not to short-circuit or accelerate the political process but to replace it altogether’.

The principal effect of this latest incursion by Sinn Fein into democratic politics has been to destabilise the SDLP and seriously to threaten its continuing viability. The SDLP itself must accept at least some of the responsibility for this state of affairs. It refused to go into the Prior assembly, arguing that the parameters within which that assembly would be forced to work were unacceptable. Its real fear, however, was that by participating in the new institution it would leave the electoral high ground to Sinn Fein. The party seems not to have realised that its action in abstaining has had precisely the effect it feared, and it has painted itself into a political corner from which it appears to have neither the energy nor the will to escape. The irony is that its political future at the moment is so bleak that a brave gesture could hardly make things worse. If such a gesture failed, and if the SDLP disappeared, that would not of itself necessarily be a tragedy. The best spirits in it would undoubtedly survive, and become involved in a new political grouping.

All these developments are being watched in Dublin with the mixture of alarm, incomprehension and instinctive reaction that has for some time been a substitute for policy on the North. The Leitrim killings have profoundly influenced public opinion – more so, possibly, than any of the litany of murders which afflict the North on an almost daily basis – and public support for militant Republicanism has never been lower. As far as the security situation is concerned, the Republic is playing its part to the maximum degree possible, given the horrendous state of its economy and the enormous costs involved. The Leitrim incident is not the only one in recent years in which members of the Irish security forces have been killed, but it is by far the most dramatic. It is worth noting, as Dr Townshend points out in relation to the Civil War, that native Irish governments have frequently imposed, within their own jurisdiction, security measures infinitely more draconian than any British administration has dared to implement in any part of Ireland. When Kevin O’Higgins, the Free State Minister for Justice, agreed with his Cabinet colleagues to execute four Republicans without trial as a reprisal for the campaign of political murder that was then in progress, the action evoked a degree of political support which today, with our stress on civil liberties and the rule of law, we might find altogether surprising. Internment, too, has been imposed by at least two Fianna Fail governments in the South, with none of the furore that inevitably greets its introduction in the North. As an alternative to proscription of Sinn Fein (which might create more problems than it would solve) it is undoubtedly being considered.

The New Ireland Forum, in which the Republic’s three main political parties and the SDLP are involved, has at least begun to qualify traditional Southern rhetoric about the necessity – indeed the inevitability – of a united Ireland, principally by publishing a considerable amount of material indicating that the foreseeable costs of such an eventuality would be substantial. It has also disclosed at least hair-line cracks in Fianna Fail: Mr Haughey’s traditional insistence on a unitary Irish state as the only possible solution has been obliquely criticised as simplistic by his principal rival in the party, Mr Desmond O’Malley. And what has been at least as interesting as the deliberations of the Forum itself has been the degree of interest displayed in it by Britain, and more particularly by the British press. This has led to the suspicion that the British will to remain in Northern Ireland is weakening, and that the British Government is looking hopefully to the Forum for the magic formula which will enable it to leave with dignity, and some kind of an agreed solution. The suspicion was further fuelled by a visit to Dublin by Mr Ken Livingstone, who told a large and enthusiastic audience that as Ireland was now effectively tied in to Nato, and as the costs of Northern Ireland were becoming increasingly unattractive to Mrs Thatcher’s Government, withdrawal was on the cards. Mr Livingstone’s analysis, however, was marred by flaws which have become part of the stock-in-trade of a certain Left analysis of the Northern conflict, as it is carried out in Britain. One of them is the willingness to believe any conspiracy theory, no matter how far-fetched. Another, possibly more serious, is a highly simplified view which puts Northern Ireland into the same ideological box as, say, Aden or Cyprus. This leads inevitably to a measure of support for Sinn Fein’s resistance to the ‘colonial government’ – which incidents like the Harrods bomb will, one hopes, do something to dispel – and to a child-like belief that the perfidy and venality of the British Government is the only obstacle in the way of a just solution.

One does not have to believe that the British Government is the embodiment of saintliness and forbearance to place a major question-mark against this kind of analysis. Its fundamental flaw is that it has no place in its theology for the Protestant Unionist population of Northern Ireland. The extreme wing of Provisionalism does not even bother to profess concern for them, and tends to assume that when the objective of a united Ireland has been achieved they will leave of their own accord or knuckle under. The woolly-Left analysis, insofar as it considers them at all, tends to look on Dr Paisley and his followers as equally Irish and somewhat quaint survivors from another era who will undoubtedly readjust themselves to the changed circumstances as and when the need arises.

That this is a serious misunderstanding of the nature of the Unionist community in Northern Ireland, and of the political obstacle to progress that it represents, is clearly demonstrated by Dr Townshend’s perceptive and historically rich work. One of the key elements on which he focuses is the by now undeniable fact that terrorism cannot survive on myth alone, or on emotion, or on ideology. It needs at least passive support from a sufficiently large section of the community in order to overcome the inevitable reverses, both military and political, and the weight of historical evidence which indicates that its cause is unlikely ever to succeed. It gets this support in various ways, and partly indeed by intimidation, as has already been suggested. But, as Sir James Stephen remarked in 1886, ‘a very small amount of shooting in the leg will effectively deter an immense mass of people from paying rents which they do not want to pay.’ This quotation, as Dr Townshend points out, focuses upon the crucial question of the objectives for which a community may accept being coerced by ‘extremists’, and adds point to his observation that the level of support for militant Republicanism can be adequately explained only by ‘an inheritance of communal assumptions validating its methods as much as its ends.’ What is at issue at present is not the payment of rents, the ostensible problem in 1866, but the giving of consent to the legitimacy of the form of government under which both Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland live. If it is true that, whatever the merits of the case, this refusal of consent by Northern Catholics is the critical ingredient in the environment in which the IRA flourishes, or survives, it is also inescapable that a reversal of the situation would unleash Protestant terrorism in a mirror-image campaign against forcible incorporation in an Irish state. As early as 1914, Townshend points out, there were no fewer than four armies in Ireland: since that date, the number has hardly diminished, and the current spate of sectarian murders of Catholics in the North, for which some present and former members of the security forces have been charged, will not increase the possibility that Catholic allegiance to the Northern state will soon be forthcoming.

It may simply not be possible to defeat the modern terrorist, in a military sense, given the level of community support within which successful terrorism, whether Catholic or Protestant, is carried out. Dr Townshend’s historical researches lead him to this view, but also to the belief that there is no ‘sound reason why political solutions cannot be reached in the midst of war’. The logical consequence of this view, if accurate, is that the only long-term way of putting an end to terrorism (always assuming that you are not simply prepared, like Mr Atkins in 1979, to settle for the ‘acceptable level of violence’), is to remove or alter the conditions in which it breeds. In other words, the Northern Ireland problem has several dimensions, and only one of these is the security dimension: the other is political. The problem for politicians is that they feel that if they make political or institutional changes in a climate imbued with violence and terror, this is tantamount to recognising the political justice of the terrorists’ demands.

The terrorists’ demands, however, are in each case clearly identifiable. On the Catholic side, they amount to a demand for the withdrawal of the British presence in Northern Ireland, come what may. On the Protestant side, they express opposition, not just to the perceived threat of a united Ireland, but to virtually any political developments, no matter how beneficial in themselves, which involve a weakening of Protestant power. Political action does not necessarily involve recognition, much less acceptance, of either of these sets of demands. It does not follow that the only mechanism which will produce the required degree of consent to government on the part of the Catholic community is a united Ireland. Nor does it appear inevitable that tackling the political problem posed by Protestant obduracy, in a context in which their veto on specifically constitutional change has been fully recognised, will have the dire consequences some Protestant leaders threaten.

The political problem of Northern Ireland is not just the problem of Irish unity, as it tends to be perceived in the South, in the United States and elsewhere, and in some sections of British public opinion. It can also be perceived as a problem of British unity. In other words, the key question is whether the political decisions being taken, and the political options being opened up, are designed to make it more possible for the Northern Catholics to live peacefully as a minority within the British state, or for the Northern Protestant to live peacefully within an Irish state. There are many national minorities within European countries, and some of them are more peaceful than others. The existence of a national minority, moreover, is not of itself necessarily productive of violence and terror. It is at least as theoretically possible that there could be a peaceful Northern Ireland within the United Kingdom as that there could be a peaceful Northern Ireland within an Irish state. In practice, the options are not equal, and presumably British government policy at the present time favours the first. If it does, the most logical course of action would seem to be to reinforce the Unionist veto on constitutional change by whatever means may be considered necessary – the veto is, in itself, meaningless, for the very simple reason that the votes of the million Unionists form the most effective veto of all – but to combine this reassurance with the most uncompromising set of conditions for devolution. These conditions should be aimed principally at Unionist intransigence, because Unionists have considerably more to lose than Nationalists by adopting a policy of abstentionism, and so are probably, when the chips are down, prepared to pay a higher price. The Prior Assembly very nearly worked, and was probably constructed along the right lines for such an initiative: but the balance of advantage and disadvantage was fractionally, and critically, wrong. A new move is more likely to be successful if it recognises that the fundamental difficulty in the government of Northern Ireland is not the absence of a potential government, but the absence of a potential opposition: for oppositions legitimate governments at least as much as do electorates. And if there is a price to be paid for peace, it is logical that the greater price should be paid by those with the greater power. Such a policy might not only do more to solve the security problem than any amount of expenditure on police overtime and rubber bullets: it might, ironically, do more to copper-fasten Northern Ireland within the Union than any security policy alone, no matter how sharp its cutting edge.

The historical evidence presented here for our inspection has a powerful relevance to many aspects of the current conflict. The overall view tends to exonerate Britain – at least from the charge of unwillingness to try and solve the problem: the difficulty has been, Townshend implies, that the solutions adopted from time to time have been inappropriate, or ham-fisted, or applied in the wrong combinations, and have always been threatened, as the English Liberal John Morley succinctly observed, by the fact that ‘the Irish are more provoked by the extension of force than they are gratified by the extension of justice.’ Townshend concludes: ‘history may suggest that certain realities lie outside the scope of political manipulation.’ All political planners, on either side of the Irish Sea, have to accept the possibility that he might be right.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.