In Roman mythology, the god Terminus presides over walls and boundaries. He expresses the ancient doctrine that human nature is limited and life irredeemably imperfect. Terminus agrees with Robert Frost in saying ‘good fences make good neighbours’; and he also takes a classical view of artistic creation by insisting on formal constraints and closed symmetry. Although Terminus inhabits hedges and drystone walls, he is not a property of pastoral verse, and this is because pastoral writing, like fantasy writing, is a convention which licenses an imaginative freedom from reality. In fantasy literature the result is the ennui of Utopia, a luminous envelope that absorbs the world.

In The Passion of New Eve, a fantasy of late-Seventies America, Angela Carter’s androgynous protagonist describes a room like this:

Soft clouds of dust rose from the yellowed pelts of polar bears flung on the floor and their mummified heads roared mutely at us in balked fury. The walls of this long, low, serpentine room were made of glass tiles, so we could see the undersides of more furniture upstairs, and here and there the back of another rug – all dim and subtly distorted.

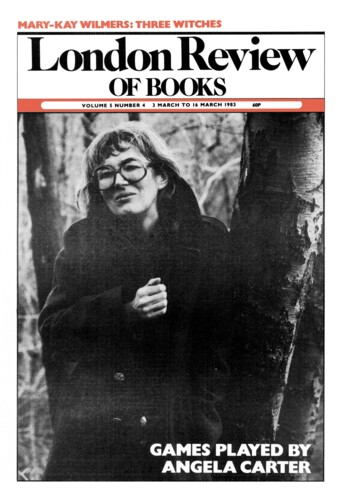

Reading this passage of descriptive narrative, I asked myself how the walls of a fantasy room could possibly be distorted? The problem is ontological: fantasy by its very nature is a distortion of reality, therefore a distorted effect within a distortion must be something which appears incontrovertibly and recalcitrantly real – a positivist with a half-brick, for example. The easy fluency and soft stylishness of Angela Carter’s Fictions is won at the expense of form and mimesis, and the result is an expansive territory without boundaries or horizons, a kind of permanent and infinite vanishing.

Carter’s journalism, however, is remarkable for a style which arches brilliantly between sociological observation and self-delighting irony. This introductory paragraph is emblematic of her technique:

Getting a buzz off the stones of Bath, occupying a conspicuous site not fifty yards from the mysterious, chthonic aperture from which the hot springs bubble out of the inner earth, there is usually a local alcoholic or two on the wooden benches outside the Abbey. On warm summer afternoons they come out in great numbers as if to inform the tourists this city is a trove of other national treasures besides architectural ones. Some of them are quite young, one or two very young, maybe not booze but acid burned their brain cells away, you can’t tell the difference, now.

Bath is a Roman city and that adjective ‘chthonic’ derives from the Greek word for ‘earth’. Carter has a pre-Christian concern for the spirit of place and the springs of particular cultures. Characteristically, she seeks to locate the folk imagination and its congenial ethnicity within those clean well-lighted spaces we call ‘reality’. She enters an antiseptic world called Arndale Centre and then discovers the yeastiness of real culture: curd tarts, balm-cakes, live pigeons, and local cheeses wrapped in ‘authentic mired bandages’.

In Bath, Carter discovers ‘a lot of fine-boned, blue-eyed English madness’ which forces her to insist on her Scottish extraction and see the city wryly as ‘an icon of sensibility’. Her sophisticated primitivism designs this vividly intelligent image:

That golden light, the light of pure nostalgia, gives the young boys in their bright jerseys playing football after tea in front of Royal Crescent the look of Rousseau’s football players caught in the amber of the perpetual Sunday afternoon of the painter. The sound of the voices of the children contains its own silencing already within it: ‘Remembered for years, remembered with tears’.

Douannier Rousseau was loved by all his friends for his saintly and peaceable personality, and his extraordinary marriage of quotidian reality with fantasy is current at the moment. In ‘A Whole School of Bourgeois Primitives’, for example, Christopher Reid designs another version of England caught in a moment of buzzy stasis:

Our lawn in stripes, the cat’s pyjamas,

rain on a sultry afternoon

and the drenching, mnemonic smell this brings us

surging out of the heart of the garden:

these are the sacraments and luxuries

we could not do without.

Welcome to our peaceable kingdom,

where baby lies down with the tiger-rug

and babies roll over like puppies

inside foxglove-bells ...

Like Reid, Carter is busily and wittily designing a new form of the English sensibility – an ironic, ludic, cultivated imagination which is free from class guilt, bored by the old-fashioned idea of Great Britain, peace-loving and generously multi-racial. Carter sees England as a crowded and shabbily decent third-world country, and she shares with Reid and Craig Raine a splendidly Mediterranean sense of joy. Where Larkin and Motion are the troubled elegists of a vanished world power, these writers inhabit the liberated atmosphere of light-filled studios. They are flâneurs in an English market that resembles ‘the peasant markets of Europe’.

Carter has a special affection for Yorkshire and in this description of Bradford she creates that sense of the marvellous which is essential to the folk imagination:

Like monstrous genii loci, petrifications of stern industrialists pose in squares and on road islands, clasping technological devices or depicted in the act of raising the weeping orphan. There is something inherently risible in a monumental statue showing a man in full mid-Victorian rig, watch chain and all, shoving one hand in his waistcoat à la Napoleon and, with the other, exhorting the masses to, presumably, greater and yet greater productiveness.

This is the new post-imperial sensibility singing its delighted sense of being free from all that pompous gruffness which goes with a concept of progress and national destiny. Carter is the laureate of de-industrialised England and the hedonistic egalitarianism of her prose – like Ashbery with stringency – makes her the most advanced stylist in the country. With a bemused delight, she creates an England of ‘disparate ethnic elements’ – black puddings, signs in Urdu, bottles of Polish vodka next to ‘the British sherry, brown ale and dandelion-and-burdock’. Although she draws on Orwell’s essays in popular culture, Carter’s prose style lacks his strenuous puritanism: the weather of her style is warmly catholic and familial, where Orwell’s style often seems solitary, private and rather chilly.

Like Christopher Reid, Carter is fascinated by Japan, and her accounts of Japanese culture have a quality reminiscent of the ‘charm’ which nuclear physicists attribute to certain atomic particles. Carter is ‘quarky’ rather than ‘quirky’, and she possesses a rare ability to write about the unusual and ridiculous without disdain:

One stall sells cocks made of bright pink sugar at 75p a time. In the course of the afternoon, they sell 300 of the things – their entire stock. One other stall, and one other stall only, sells cookies in all manner of phallic and vulvic shapes, as well as lollipops on sticks with a coy little striped candy cock nestling in a bed of pink sugar.

Where V.S. Naipaul would have drained his disgust into bad prose, Carter lets the images happen in a manner that has a direct, super-real intelligence and grace. Her account of samurai comics issues from her prefatory statement, ‘In Japan, I learnt what it is to be a woman and became radicalised’:

Tanaka perpetrates lyrically bizarre holocausts, in décors simplified to the point of abstraction. His emphasis on decorative elements – the pattern on a screen; on a kimono; that of the complications of combs in a girl’s hair – and his marked distortion of human form, create an effect something between Gustav Klimt and Walt Disney. His baby-faced heroines typify Woman as a masochistic object, her usual function in the strips.

That image of Klimt crossed with Disney is one of the most perfect moments in Carter’s prose and her essays are distinguished by a fineness of visual imagination and an ability to make abrupt and exact transitions which create a sense of relatedness among apparently disparate things. As a result, the world becomes a gregariously coloured fiction that issues perpetually from an ironic and chthonic intelligence.

Carter’s radical feminism offers startling portraits of Japanese sexuality, and she also battles sporadically with D.H. Lawrence: ‘Lawrence, the great, guilty chronicler of English social mobility, the classic, seedy Brit full of queasy, self-justificatory class shame and that is why they identify with him so much in British universities, I tell you.’ Unfortunately, prose-rhapsody cannot properly cope with the phenomenon of Lawrentianism, its canonisation by Leavis and enduringly unexamined presence on courses in English literature. Carter ought, urgently, to write a companion to The Sadeian Woman and explore, not just the assumptions on which Lawrence’s fictions are based, but the often hilarious attitudes which his benighted critics reveal when they discuss his work. She is a very distinguished stylist in her discursive prose, but her fictions suffer from the absence of what Keats termed ‘disagreeables’. It could be that her cerulean imagination would benefit from the constraints of the documentary novel.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.