Many years ago Thom Gunn remarked: ‘To write poetry without knowing, for example, about the proper use of runovers used to be considered as impertinent as it would be now to apply for a job as a truck driver without knowing how to shift gear.’ (Wearily, in a sanguine attempt not to be misunderstood, he added: ‘It is true that being able to shift gears does not mean that one can drive straight or that one has the necessary stamina to keep the job, but it is a prerequisite.’) Geoffrey Grigson, so much older than Gunn (he is 77), has of course built his career about being considered impertinent, so it’s not surprising to find in his latest collection (his first was in 1939) runovers like these:

So mud was on you that day.

So it was as if loved wheelbarrow

Paths led not to love, but

Out of love away and away, or were

Barred. So we had trite things only to say.

Will anyone tell me how the voice is supposed to manage the runover (the enjambment) from the second line into the third, the third into the fourth, the fourth into the fifth? And this is a modest example: when Grigson is being ambitious, he jolts or hurls his runovers across a stanza-break:

Extra guests she welcomes awkwardly, shop

People from the near town ...

And yet this is the poet who quotes with solemn approval:

Beauty it may be is the meet of lines,

Or careful-spacèd sequences of sound.

Well, to be sure: but what happens to ‘the meet of lines’ at ‘wheelbarrow/paths’, and ‘but/out’ and ‘were/barred’? Grigson’s precepts are often admirable, but they are addressed to everyone but himself. And that has always been the case.

Fortunately he has written better than this. His devotion to Auden is required to make up for his hatred of nearly everyone else, and he has several poems addressed to Auden. Of these, one is mawkish (‘But this morning/Is different, my dear one’), and another is so-so, but some time in the 1970s, having read Auden’s City Without Walls, Grigson wrote an Epistle in which he excelled himself:

Green pillows of cress

In the brook which begins us

You celebrate too;

And up from your verses,

Though many

Forget them, stinking

Ogres not read them,

Blest by high priests

Stiff generals not

Stoop to reject them,

Rises an odour

Of essence, I say, of

Ripeness and rareness.

This poem for Auden lovingly re-creates for him places around Grigson’s summer home in France; and readers of Notes from an Odd Country (1970) will not be surprised. France releases in Grigson moods of gratified expansiveness which mysteriously evade him as soon as he re-crosses the Channel. It can only be at his instigation that we are advised on the jacket of The Cornish Dancer to regard Notes from an Old Country as ‘the best gloss on his own poems’. And it’s no good objecting that the Channel-crossing has this effect on him: others of us have found it among the luxuries of expatriation that we can extend to the foreign culture, since we’re in no way responsible for it, an indulgence that we deny to our own tight little island. What is striking, and deplorable, is that Grigson himself seldom notices this annual change in himself, still less worries about it. It’s the same story: if England mostly if not quite invariably exacerbates him, the reason is to be found never in himself but in other people.

This unreflecting exemption of himself from the strictures that he addresses to everyone else produces effects both bizarre and unfortunate, as when (this is in Blessings, Kicks and Curses) he develops a very just and instructive distinction between Walter Scott, prepared to compromise with his public, and Wordsworth, not so prepared; then realises that this is just the distinction that Leavis would have made and, instead of welcoming Leavis as an ally, marks out his distinction from him by talking of his ‘commination and pulpitry’; only to end and cancel out his own argument by a series of comminations more sweeping and prejudiced than Leavis at his worst. The damned include, since Grigson is a Little Englander, ‘the mob of Lowlanders who write in Lallans’ (for Hugh Macdiarmid, as for many others, he has a ferocious aversion that is never explained), and ‘the mob of Welshmen who write in Welsh ...’ At any rate, and oddly enough, France – specifically the France of Ronsard, from whom he translates four poems, two of them very well – gives Grigson what England doesn’t. And yet he seems not to have though through the implications of that affinity. For Ronsard of course conspicuously lacks that painterly eye which Grigson applauds in Raoul Dufy, and all too painstakingly tries to cultivate in his own poems:

To write like the bright sap green

Which lights dry saddening banks

Beside charcoal of hard roads in the spring

(Adding rose madder and a deep sky blue) ...

Ronsard’s tributes to the Loir valley, as Grigson must surely have recognised when he translated them, are wholly poetic or rhetorical – that is to say, linguistic; they owe nothing to the painter’s nice distinctions between the pigments on his palette, nor to a naturalist’s knowledge of just how a swift differs from a swallow. Grigson’s views on the proper language for poetry would, on the other hand, make the poet subservient to both the painter and the naturalist; his notions of just what is involved in naming, and of how signification is achieved in language, are astonishingly naive – with a naiveté which it needed no reading of Franco-American theory, but simply an awareness of what was happening to him when he composed, to reveal to him. For him a word has a meaning, one right meaning and no other; and when someone suggests that the matter is not altogether so simple, ‘What piffle!’ is his comprehensive reply and rebuttal. In this bluff assurance, he is the very voice of that English (not British) Establishment which he would have us believe he has spent his life in challenging.

He is too old to change now. And rather plainly these books appearing all at once represent a generous attempt by Grigson’s publishers (who are ill-served by their proofreaders) to claim for him what he supposedly deserves, as an intransigent and uncompromising ‘loner’. It is ill-natured, and serves no purpose, to suggest that his too much cherished image of himself as ‘loner’ is precisely what has prevented him from growing significantly between 1939 and 1982. Instead, let it be said that in his work of the early 1970s the Epistle after reading City without Walls, though it is pre-eminent, does not stand alone. Among other poems of that time which transcend in practice the deficiencies of the theory behind them, are these: ‘Short History of Old Art’, ‘Perhaps So’, two translations from Victor Hugo, ‘The Dying of a Long Lost Lover’, ‘Hill of the Bees’, ‘A Myth Enacted’, ‘Slow Bell from the High Hill’, ‘John Hunter’s Canal’, ‘The Lawn of Trees and Rocks’, ‘Quelle Histoire’, and (an unusual exertion of sympathy) ‘Dulled Son of Man’.

In a poem to Ivor Gurney, Grigson, who can sometimes be magnanimous to the dead, hails Gurney as a poet of ecstasy. In his own case, it is his hatreds that are ecstatic, and one wonders how he would get along if Larkin and Alvarez and I were not around to be hated. (Grigson doesn’t take sides – he’s agin us all.) So there may be truth to the hysterically ugly sentiment of some lines on how Alvarez might kill himself:

And that, believe me, I’d regret

Because I keep you for a pet,

And do not want to lose you yet,

My Al.

And yet, why not? Poetry burns on whatever emotional fuel it can find, and lampoons can be great poems – though only if they are in exact metre, and Grigson hasn’t the patience for that. Is there not some justice to his reproaches?

In Grigson’s career nothing is so honourable as his exertions on behalf of dead poets unjustly neglected: Smart, Clare, Christina Rossetti and (late, but significantly) Gurney. He has, I think, every right to complain that other men of letters have less consistently reviewed the canon, so as to revise it continually – which is the only way to keep it alive. To be sure, on this issue too he flings out into unconsidered judgments, having, for instance, a special rod in pickle for John Ruskin, without noticing that Ruskin alone among the Victorians asserted the rights of that splendid poet, the Countess of Pembroke.

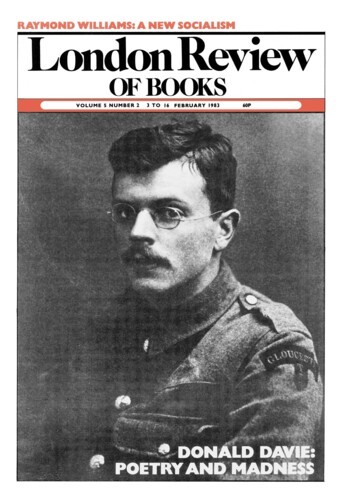

Some episodes in the history of Gurney’s poems are enough to put most of us out of countenance: in particular, the indifference that greeted Blunden’s selection in 1954, published by Hutchinson, and also Leonard Clark’s Chatto selection of 1973, for which Clark himself put up some of the money. It’s true that Blunden, thinking his own poems didn’t fit the fashions of the early Fifties, tried to second-guess the reviewers by making an eccentric selection from Gurney; and both he and Clark handled only what are now seen to be inaccurate typescripts. All the same, there should have been someone, on both occasions, able to stand back from the rivalries with his contemporaries for long enough to see virtue in this poet who had died in an asylum in 1937. Certainly I blush to recall that it was the Russian poet Joseph Brodsky, a year ago in Nashville, Tennessee, who asked me if Gurney didn’t excite me, and I wasn’t able to answer.

It is hard to find excuses. Both Blunden and Clark printed, for instance, ‘Townshend’ – a poem that honours a man who was patron to Ben Jonson:

Knowing Jonson labouring like the great son he was

Of Solway and of Westminster – O, maker, maker,

Given of all the gods to anything but grace.

And kind as all the apprentices knew and scholars;

A talker with battle honours till dawn whitened the curtains,

With many honourers, and many many enemies, and followers.

The third line here conveys what Leavis would call ‘a limiting judgment’; and this had been anticipated in a poem to Beethoven that appeared in Blunden’s selection, and Clark’s (and also in Music and Letters in 1927):

You have our great Ben’s mastery and a freer

Carriage of method, spice of the open air ...

Which he, our greatest builder, had not so:

Not as his own at least but acquirèd-to.

The judgment on Jonson limits him indeed, but only in the sense that it defines and characterises his excellence: not in any way to devalue ‘our great Ben’, ‘our greatest builder’, ‘labouring like the great son he was’. And nothing more clearly marks off Gurney in his generation. Many of that generation vowed themselves, as Gurney did, to the great Elizabethans and Jacobeans, but no one else gave pride of place to the most laborious of those masters. Gurney sets no store at all by ‘spontaneity’, except as an effect, an illusion achieved by great labour. And even the effect, precisely because he had himself achieved it in his beautifully mellifluous early work – see ‘Only the Wanderer’ from Severn and Somme (1917), or ‘To His Love’ from War’s Embers (1919) – ceased to be anything that he aimed for at all often. Labour, hard study and relentless practice, making, building – the emphasis is constant. Moreover, from P.J. Kavanagh’s warm and judicious Introduction, but also from the poems themselves, we get the clear impression that Gurney in the years after demobilisation went without sleep, went without food, quite simply overworked himself into his mental breakdown – which certainly wasn’t any direct consequence of his trench-experiences. So far from being a nature-poet, Gurney is a poet of, and ultimately a martyr to, Art. He knows, and repeatedly asserts, that all the beauties of his beloved Gloucestershire are fugitive and therefore unconsoling unless someone like himself – and there is no one else, as he knows exultantly – can catch and seal them in the art of music or the art of poetry, or in the two arts married.

The strenuousness of this conception is not only asserted in the poems, it is enacted there, as in the wrenched compactness of ‘Given of all the gods to anything but grace’, or (the same point rephrased) ‘Not as his own at least but acquirèd-to’. Both phrases are perfectly clear, yet each is as far as possible from what the insufferable Robert Nye commends in the diction of Grigson: ‘how close that idiom comes to living speech’. Much virtue in that ‘living’! For Gurney, the life that there is in English speech has been injected into it by lonely, learned and masterfully artificial speakers like Ben Jonson; our conviction that life in our speech is found on the contrary in what is casually spoken, and as casually overheard, in a corner of the saloon bar – this is the most likely, at all events the most respectable reason why the poet Ivor Gurney has never yet got from us what, as he knew, he deserved. ‘A freer/Carriage of method’ – this too has never been heard in any saloon-bar: but how much more of the history of our tongue, how much more resonance, how much more life it has, than anything that might be heard there!

Gurney’s third collection, Rewards of Wonder (1919-1920), was rejected and never published. (Nor was any other in his lifetime.) The publishers were right to reject it, and Gurney was right to be undeterred. As we read it in this volume, Rewards of Wonder seems to represent a violent mutilation by this lyrical poet of his lyric voice. There is one exercise after another in headlong mostly couplet rhyme, much of the time intolerably strained and grotesque, looping up extremely heterogeneous matter into six-foot or even seven-foot accentual lines. One such poem is called ‘What I will pay’ (he means, for artistic mastery) and what Gurney will pay is unceasing work, and emulation of ‘Beethoven, Bach, Jonson’, all so that he may ‘write fair on strict thought-pages’. The harvest of this violence, the reward for which this price was paid, would come later.

It came soon, in the more than a hundred poems that P.J. Kavanagh dates between May 1919 and September 1922, when Gurney was committed to a private asylum, Barnwood House, Gloucester. These are the poems that tell us we are in the presence of a great poet. Not many of them are consummated masterpieces. We shall be told that Gurney was too big a poet to bother about perfection. But this is, to take a leaf out of Grigson, piffle. All poets worth their salt, and Gurney among them certainly, aim at perfection: but when poems are coming at the rate of one or more a week over a period of two years, there just isn’t time for perfecting. Accordingly, this work is rich in magnificent torsoes, passages of breathtaking mastery following starts that are merely and hastily roughed in. My fingers itch to copy them out. What strikes first is Gurney’s unfailing touch with what Barbara Herrnstein Smith has taught us to call ‘closures’. Even in Rewards of Wonder this had been evident, when brutally rhymed pieces would abandon rhyme so as to end on a heart-breaking cadence. Similarly here many a rough-and-ready piece is all but redeemed at the last moment by a closing line that is much more than a summing-up or a sweet coming-round: ‘And his man’s friendliness so good to have, and lost so soon’, or ‘And beauty brief in action as first dew’. What is even more to the point, because it is new, is Gurney’s mastery of decorum. He now has at his command any number of distinct styles, and he chooses one or another according as the occasion requires: the ceremonious stateliness of ‘Sonnet to J.S. Bach’s Memory’ can be let down to turn a graceful compliment on the bicentenary of a local paper (‘On a Two-Hundredth Birthday’). The lyric voice, so savagely extirpated from Rewards of Wonder, can now be re-admitted because the poet has a sure sense of when it is appropriate, when not. The influences – Hopkins in ‘George Chapman – The Iliad’, Edward Thomas in ‘On Foscombe Hill’ and ‘Up There’ and possibly ‘Imitation’, Jonson in ‘We Who Praise Poets’, Whitman and possibly D.H. Lawrence in ‘Felling a Tree’ – are discernible but never for certain, because so thoroughly assimilated and turned to purposes that the originals would not have contemplated. ‘Felling a Tree’ draws on the Romanticism of Whitman and/or Lawrence to enforce a thoroughly classical, because Roman-imperialist, sentiment. (Gurney is keenly aware of the Roman presence in his Gloucestershire.) And similarly ‘We Who Praise Poets’ is not Jonsonian pastiche, because its Jonsonian diction is carried on a more than Jonsonian restiveness and barely controlled turbulence in the metre. Of the ten or so poems in this section that are perfected, Blunden or Clark or both picked up several: ‘The Sea Borders’ (very Whitmanesque), ‘Andromeda over Tewkesbury’, ‘Clay’, ‘The Bare Line of the Hill’, ‘The Cloud’, ‘From the Meadows – The Abbey’, ‘The Not-Returning’, ‘Looking There’ and ‘Sonnet – September 1922’. They missed ‘We Who Praise Poets’, and also ‘The Valley Farm’:

Ages ago the waters covered here

And took delight of dayspring as a mirror;

Hundreds of tiny spikes and threads of light.

But now the spikes are hawthorn, and the hedges

Are foamed like ocean’s crests, and peace waits here

Deeper than middle South Sea, or the Fortunate

Or Fabled Islands. And blue wood-smoke rising

Foretells smooth weather and the airs of peace.

Even the woodchopper swinging bright

His lithe and noble weapon in the sun

Moves with such grace peace works an act through him;

Those echoes thud and leave a deeper peace.

If war should come here only then might one

Regret water receding, and earth left

To bear man’s grain and use his mind of order,

Working to frame such squares and tights as these.

The runover, ‘Fortunate/Or Fabled’, is magisterial, and so is the audacious handling of the pentameter three lines from the end. Moreover, Gurney is in earnest: so far is the Severn valley from being a constant standard by which history’s vacillations are judged, it is itself, and rightly, a symptom or register of man’s history – let it be inundated afresh, and removed from man’s dominion, if that dominion eventuates in what Gurney had seen in France. P.J. Kavanagh is very good on the Great War as Gurney experienced it; far more than Isaac Rosenberg’s war, Gurney’s is the war of the private infantryman, as against the subalterns’ war of Owen or Grenfell, Sassoon or Blunden or Graves. Because he is not of the officer class, he feels no responsibility for the horror, hence no guilt about it, and so his revulsion from it is manageable. He is nearer to David Jones; one ‘soldiers on’. His revulsion and protest come later, when post-war England makes light of its soldiers’ sacrifices: ‘How England should take as common their vast endurance/ And let them be but boys having served time overseas.’ As Jeremy Hooker has noted, the crucial word is ‘honour’: England refuses to honour the draft that Gurney, as soldier, musician and poet, has drawn upon her. And so in the poems of this period we detect increasingly a note that may be called confessional or indignant or both, as in ‘Quiet Fireshine’, ‘Kettle Song’, ‘The Bronze Sounding’, ‘Strange Hells’; mounting in Mr Kavanagh’s arrangement to a crescendo of accusation in ‘The Not-Returning’, ‘Looking There’ and ‘Sonnet – September 1922’, all three of them consummated statements. As we have seen, the draft upon England was still not honoured as late as 1973.

The next poems, written in asylums, reveal immediately a development least to be expected by anyone who has followed Gurney’s career to this point: his style becomes plain.

Why have you made life so intolerable

And set me between four walls, where I am able

Not to escape meals without prayer, for that is possible

Only by annoying an attendant. And tonight a sensual

Hell has been put on me, so that all has deserted me

And I am merely crying and trembling in heart

For death, and cannot get it. And gone out is part

Of sanity. And there is dreadful hell within me.

That is addressed ‘To God’; and though it is the cry of a soul in torment, it is also poetry. Nor does the plain diction come only with anguished themes: we find it in ‘Cut Flowers’, or in ‘The Mangel-Bury’, which starts out with the astonishing plainness of ‘It was after war; Edward Thomas had fallen at Arras ...’

By this stage we are no longer reading for pleasure, in any ordinary sense. If there is gratification (as there is), it is of the unearthly and inhuman sort that has to do with the indomitable spirit of Man, or suchlike unmanageable notions. And in any case Gurney is by now deranged. After the appalling plainness of a poem called ‘An Appeal for Death’, there come 30 poems which are, with only one or two exceptions and marginal cases, unhinged, incoherent. Blunden and Clark are to blame for printing many of these, and even Mr Kavanagh, who says finely, ‘It is a period from which an editor would like to rescue him,’ seems to think some of these pieces can be salvaged. We have all heard about ‘the lunatic, the lover and the poet’: but not Shakespeare nor anyone else can excuse us for being light-minded and unfeeling about the madnesses of mad poets. There are those who positively welcome such disorder, as if it authenticated a poet’s vocation. But great poetry is greatly sane, greatly lucid; and insanity is as much a calamity for poets and for poetry as for other human beings and other sorts of human business.

Much more surprising and admirable is a group of half a dozen poems on American themes, which both Blunden and Clark significantly passed over. They are entirely sane, because judicious: on Whitman, on Thoreau, on Washington Irving, on George Washington’s America (‘Portraits’ – perhaps the finest reflection on American history by an Englishman), Gurney passes firmly a commonsensical and limiting but in no way deflating judgment, just such as he had pronounced on Jonson. ‘The New Poet’ and ‘To Long Island First’ ought to derail in advance the attempt that will doubtless be made to enrol Gurney in the service of a supposedly native alternative to ‘modernism’. Apparently there is a great deal more Whitmanesque writing yet to see the light: for Mr Kavanagh’s exemplary edition is, it should be noted, a ‘Collected’ not a ‘Complete’, and there is some hint of the riches yet to be uncovered in, for instance, the splendid and not at all Whitmanesque ‘Motetts of William Byrd’, dated January 1925, which is relegated to an Appendix.

Astonishingly, the piteous story had still not run its course. There was, it seems, around September 1926, one more spurt of poetic energy; and it produced, along with more of that painful incoherence to which we are too ready to accord ‘rough power’, work of a quite unprecedented kind which Mr Kavanagh calls ‘timeless classical utterance’. ‘Classical’, I think, can be given a quite precise meaning. For in one of several poems where Gurney tries with some success to reconcile himself to what he sees as England’s ingratitude, he adjures swallows to abandon England in favour of ‘the shelves/Of Apennine ... or famed Venetian border’; and in a series of short but exquisite pieces that might even be called ‘imagist’ Gurney evokes with plangent severity Graeco-Roman or Mediterranean emblems like Pan or ‘a cup of red clay/Sparkling with bright water’. The failure of this manoeuvre is also recorded – in a piece called (the title tells its own tale) ‘Here, If Forlorn’. Mr Kavanagh says of these poems that ‘though sometimes good, they seem bloodless compared to the previous work’ – and the sentiment is understandable, though it will not be shared by readers who set less store by ‘blood’ than by a pure diction. The last poem in the volume, ‘As They Draw to a Close’, is Whitmanesque and magnificent.

To most people, I daresay, and in most ways, Gurney the letter-writer will seem more engaging than Gurney the poet. It is from the letters, naturally enough, that we get the most vivid impression of Gurney’s courage, his cheerfulness, his deprecating humorous tact, his anxiety under the most adverse circumstances to entertain, to have and provide fun. And yet the Gurney of the letters is, by and large, the author only of the less consequential poems. Partly this is because R.K.R. Thornton, working on a limited budget, chose reasonably enough to represent only the soldier, the Gurney who was yet to write the poems by which he has a claim on us. In fact, the Gurney who writes from the trenches still thinks of himself as musician first, poet a long way second; who accordingly measures his fellow musicians against a far more exacting standard than his fellow poets. Hence his extraordinary response to a magazine sent to him in France by his devoted correspondent, Marion Scott: ‘just what England needed – a magazine devoted to the interests of weak but sincere verse. Local poetry, local poetry is Salvation, and the more written the better.’ This is the same letter in which he harshly judges the musician Granville Bantock as ‘diffuse and ineffectual, and needs a great deal of material to make any effect’. For Gurney in 1917 poetry was not a fine art, as music was, and so he can quite blithely accept that his poems do not meet the standards of Robert Bridges, or of Milton behind Bridges. Yeats’s Responsibilities did force him reluctantly to acknowledge that poetry, too, exacts a discipline, that spontaneous imperfection and ‘sincerity’ and local loyalties won’t suffice for: ‘You will find that when I come to work again, I also shall show much greater scrupulousness than before ...’ That was a perception, however, that Gurney at that point couldn’t hold on to. And his free-wheeling or light-hearted oscillation about past masters like Milton or Wordsworth, or about near-contemporaries like Rupert Brooke and Sassoon, reinforces the testimony of teachers at the Royal College of Music before the war – that Gurney was unteachable. For all his charming self-deprecations, Gurney was, before and during the war and after it, wilful, headstrong. And this, though it just may have been the precondition of his achieving what he did, seems to have prolonged his apprenticeship to the point where the strain of it broke a personality diagnosed and self-diagnosed as ‘neurasthenic’. And incidentally, does ‘neurasthenia’ have a different or firmer meaning now than it had in 1912 or 1917? Uninstructed about this, we are quite at a loss before Gurney’s aborted suicide attempt in 1918.

Gurney in 1915 approached poetry through the mish-mash of ignorant and sentimental prejudices that we call, as Gurney did himself, ‘Georgian’. Though within a few years his trench experience, on the one hand, and, on the other, his readings in Whitman and Tolstoy, had shown him how the Georgian frame of reference would not hold up, we have no evidence, from the documents so far put before us, that he radically rethought his originally Georgian position. And if he didn’t, the consequent gulf between theory and practice must have been one more disruptive tension inside a personality that always was, and knew itself to be, precariously balanced. How inadequate the Georgian vocabulary was for explaining to him where he had got to, and what he must do next, appeared from his verdict on his own Severn and Somme: ‘I have made a book about Beauty because I have paid the price which five years ago had not been paid. Some day perhaps the True, the real, the undeniable will be shown by me and I forgive all this.’ If we translate the Keatsian or sub-Keatsian vocabulary, we can see that this was a just and unsparing assessment of himself at this stage: but how obfuscating is this opposition of undefined Beauty to undefined Truth! And how incapable Gurney was of probing beneath such lax formulations may be seen from his sole comment on Imagism: ‘As for the Imagists – I hate all attempts at exact definition of beauty, which is a half-caught thing, a glimpse.’ What survives him, not dated at all but a persistent claim upon us, is: ‘I have paid the price.’ He had indeed; and in these letters we see him paying it.

This Gurney was a prodigious poet; beside his achievement, Wilfred Owen’s and Edward Thomas’s seem slender at best. And Eliot? And Pound? Why yes, take them too in, say, 1925, and Gurney had outdistanced them – in the range of first-hand experience he could wrestle into verse, and even in the range of past masters in English whom he could coerce and emulate so as to digest that experience. The strain of the achievement was intolerable, and it broke him. Just why or how, it’s impossible to say: though it seems that he soon set his face against irony, and irony, which we have overvalued for so long, is often – as we have learned to our cost – self-defensive.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.