In Abel Gance’s film Napoleon there is a brilliant sequence in the Revolutionary Bureau of Indictments. The walls are stacked to the ceiling with the files of known, suspected, possible and deeply fanciful enemies of the Revolution; some are bulky, well-researched dossiers, others the constructions of dishonest, mean-spirited score-settlers. This key office of the new masters exudes smugness, oafishness and fear (might it be their turn next?). Every so often, a clerk is winched up towards the ceiling on a precarious pulley system, a file is taken down, and another execution is assured. Once your dossier has reached the Bureau there is no way of avoiding the tumbril – except one: in the corner of the office sit a pair of humble, twitchy, freedom-loving scriveners, who are quietly eating their way through one of the indictments.

The offices of Number 34 Greek Street must often appear like this in the sweating imaginations of a surprisingly large number of people. Nescafé society lives in fear of the time its file is called for; groping publishers can now expect a metal-edged ruler to come down and chop off their hands; homosexual vicars and provincial scoutmasters dread the day when some anonymous tip-off – a letter signed with a false name and address is always good enough – will cause Private Eye’s pitiless stare to be fixed on them. ‘If they’re dead they must be Vietcong’ has its local variant in ‘If they’re in the Eye they must be guilty.’ To some it must seem that the only way to avoid our modern version of the guillotine is to infiltrate some strong-jawed typist into 34 Greek Street and have the relevant folder munched away.

It has been a remarkable transformation. Twenty years ago the Eye was a struggling lampoon which would cheek the Home Secretary and run for cover: now it has become a moral Domesday Book in which sins are recorded for the edification of the future and the gratification of the present. The puritanical Richard Ingrams, who neither smokes nor drinks, and lives a scandalously chaste life, appears to many like some rumpled, corduroy-jacketed Robespierre (though Robespierre was a sybarite by comparison, diluting his water with wine). How has this change come about? How has the school sneak, who spent years flicking bits of inky bunjee at everyone, suddenly become a prefect?

In two ways. First, this reputedly anti-Establishment magazine has always lived comfortably within the body of the Establishment. By birth, education and marriage, most of its main contributors are respectably upper-middle-class (Osbert Lancaster recently dubbed Ingrams ‘a terrible snob’); it was founded with private money, and now, like other flourishing firms, boasts a pension scheme and a company villa in the Dordogne. Secondly, as Patrick Marnham demonstrates in the course of his amiable and rambling volume, the magazine has always been a highly permeable organisation. Where once its politics were leftish, its stance investigative, and its key influence Paul Foot, now its politics are rightish, its stance prurient, and its key figures Nigel Dempster, Peter McKay and Auberon Waugh. The radical lampoon has become required reading on the magazine syllabus of every Sloane Ranger.

Moreover, the Eye, that fearless exposer of the faintest mafia, now runs a comfortable little establishment of its own. Consider how this book might appear to an outsider: a history of the Eye, written by a long-term staffer of the Eye and co-published by the Eye. Reviewers? Auberon Waugh in the Daily Mail; John Wells twice, once in Harper’s and once in the Times; Christopher Booker in the Spectator; Malcolm Muggeridge in the Daily Telegraph; Candida Lycett-Green (who was in love with Ingrams at Oxford, speaks adoringly of him in this book, and once worked for the Eye) in the Standard. Nor are the paper’s smallest private squabbles denied space in the press. Marnham asserts in his book that a change came over Ingrams when he gave up drink; Ingrams replies to the charge with a two-column article in the Spectator. Marnham asserts (perhaps jokingly) that Auberon Waugh is ‘partly Jewish’; Waugh spends much of his review dwelling on the fact that Marnham is fortyish and unmarried (thereby inviting Daily Mail readers to draw their own conclusions).

And like other establishments, Private Eye has an excellent defence system. ‘Don’t sue the Eye’ used to be a popular rule in certain quarters: the fledgling journal was basically on the right side, and needed all the help it could get. Nowadays, the rule still applies, but for a different reason: it’s impossible to emerge from the case without a. seeming pompous, humourless and wicked; and b. ensuring for yourself at least an extra year of frenzied public ridicule. Writing letters of complaint to the Eye is almost as useless: if they are directly phrased, they will appear under deflating headlines like ‘Boring’ or ‘A Pseud Writes ... ’; if they are indulgent corrections (‘Dear Richard, Look, I’ve subscribed to your organ for 375 years, but frankly ... ’) they come across as horribly whining. The only effective way of replying to some careless cruelty or libellous inaccuracy was once explained to me by a distinguished Fleet Street wheeler-dealer. You wait until about 2.30 on the Tuesday afternoon of the Eye’s non-publishing week, and then ring the editor on his closely-defended telephone number in the country. For some reason, Ingrams – though himself fearless in printing Bruce Page’s home number and inviting readers to call it – doesn’t like this much: but, undeterred, you engage him in a conversation which just happens to puncture his siesta. You express, of course, not hurt or anger at your treatment by the Eye, but sheer professional puzzlement that it could have got things so wrong. How could anyone have been so incompetent as to misread your profit-and-loss figures by a factor of ten? It almost defies belief. You really want to discuss the matter in as long, detailed and amicable – but especially long – a way as possible. In fact, you might very well allow yourself to become rather a bore on the whole subject. You might go on a bit. You might even have to call back later if you remember something you’ve forgotten.

Private Eye began in 1961. Ingrams wanted to call it the Bladder. Andrew Osmond wanted to call it Finger. At the same time, Bruce Page was discussing a gossip-and-disclosures magazine with Christopher Booker; Page wanted to call it Bent. Though he later became an occasional butt of the Eye, Page is an editor with very similar instincts to those of Ingrams. Both adopt the basic stance that everyone in power is corrupt until proved spotless; both have obsessive streaks which they indulge without heed for the patience of their readers; both are a touch paranoid (Page asserts that paranoia is a vital factor in the make-up of a good journalist); both inspire a sort of irritated affection in those who work for them; and both have a high success rate in defending libel actions. (One of the first rules is never to offer anything for free. In the New Statesman’s Weekend Competition Gavin Ewart once mistakenly implied that the actor Roland Culver was dead. Mr Culver – whose name had only come up in the first place because it rhymed with ‘vulva’ – threatened to sue for potential loss of earnings. Page refused to let the Weekend Competition print even a polite line admitting that the actor was still alive.)

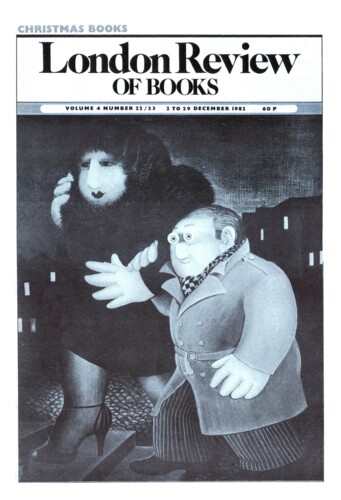

Private Eye is, as Christopher Booker found himself exasperatedly reminding Marnham in his review, ‘first and foremost a funny magazine’. Its bubble-covers have the impact and memorability of Thurber cartoon captions (‘Verwoerd – A Nation Mourns,’ Eye-addicts quote nostalgically to one another, and ‘It’s Lady Slagheap!’); it runs excellent fantasy-parodies (One for the Road, the third collection of Dear Bill letters, is a gleeful addition to the canon); and it has employed some of the best cartoonists around. Marnham is disappointingly uninformative on the graphic side of the Eye, which crucially helps its appeal as the adult’s comic. There’s an interesting paradox, for instance, in the fact that the magazine which published some of the leading graphic satirists of the age (Gerald Scarfe’s senilely brooding Churchill must be one of the finest covers of the last twenty years) has always been laid out in so amateurish and Cow-gum a fashion that it makes Isis look like Harper’s Queen.

Yet the funny side of Private Eye is not that different from a lot of mainstream humour (many of their cartoons are merely the unprintable overflow from other magazines); and besides, its quality has more or less held steady down the years. It is, of course, the gossip-and-disclosures side which gives the Eye its particular place in social and journalistic history; and this investigative side – on which Marnham rightly concentrates – has fluctuated wildly in performance. Heart Transplants, Ronan Point, Maudling, Poulson, Sanctions – the Eye’s battle-honours are highly impressive. The trouble is they were all won in the paper’s first decade rather than its second. The great days of the magazine are undeniably over, whatever the current circulation figure of 191, 000 seems to imply (but then, if we listened to circulation figures, we might conclude that the Sun offered the best Fleet Street coverage of the Falklands war).

Over the last five or six years, there have only been three significant long-running stories: the Helen Smith case, the Thorpe trial and the Goldsmith imbroglio. In the first, the Eye is merely – though admirably – allying itself to someone else’s valiant and obsessive personal quest; the second is an example of the passive scoop (police officers deliberately leaked Thorpe interviews to the Eye so as to force the lethargic hand of the DPP); while the third, for all its drama and farce, arose not out of some major investigative disclosure but out of a piece of inaccurate gossip. The Goldsmith case, though presented in the usual David-and-Goliath terms, in fact confirmed the established strength of the Eye: Goldsmith, who hadn’t been much in the public view since his elopement with Isabel Patino, ran headfirst into the magazine’s rare power to make its opponents first notorious, then ridiculous, and ultimately fictional. Ingrams to this day keeps a life-size cut-out figure of Sir James in his office – an appropriate touch, since the main result of the case (officially an expensive score-draw) was to turn Goldsmith into Goldenballs, the plump businessman into the cardboard villain. Geoffrey Wansell usefully restores a third dimension to Sir James Goldsmith in his fair and detailed portrait of this richly dislikable tycoon; those happy with the usual two will prefer Ingrams’s own deftly mocking Goldenballs.

The Eye’s big campaigns have now given way to disclosures in specialist areas (the turf, the City), and the investigative side of the paper is more or less stagnant. Ingrams shows no signs, for instance, of recycling some of his profits to employ a journalist actually to find things out. This is part of a wider stagnation documented by Marnham. The last editorial initiative made by Ingrams was in 1970, when he hired the berserk columnist Auberon Waugh, while the key date marking off the Eye’s first phase from its second is 1972, when the magazine eased out Paul Foot and gained the malign Nigel Dempster. Since then the Eye – like the Sun – has moved calmly to the right. Anyone studying the magazine over the last few years and recalling the Eye’s successive attitudes to Macmillan, Home, Wilson and Heath might be astonished at how lightly Mrs Thatcher and her cabinet of yes-men have got off. But then the Eye’s current self-image – of stout, no-nonsense, undeceivable conservative Englishness – isn’t so very far away from that of the Prime Minister herself. In a couple of years’ time, no doubt, the magazine will open its own wine club, and then we shall all know exactly where we are.

Marnham’s book is a hybrid, sometimes quietly astringent towards Eye personnel, at other times oddly characterless: rather than counter an anti-Eye argument under his own name, he is apt to quote a piece of Evelyn Waugh’s journalism, written decades earlier, which he seems to assume will do as a reply. The book lacks any attempt to assess the magazine’s new readership (we have to make do with a single observation made on a train by Michael Heath); it peters out badly in a classic ‘cont. p94’ fashion; and is in places very slapdash. For instance, Marnham’s key theory of the gear-change in Ingrams’s character – a boozy, ribald funster who in 1967 went off the sauce and emerged a moody, ruthless, middle-aged puritan – is introduced thus: ‘As a young man he was an unforgettable sight, once described by James Fenton in the New Statesman... ’ Yet Fenton’s description of the unforgettable ‘young’ Ingrams was actually written in 1976, nine years after the booze cupboard was locked and the dreadful Hydeish Ingrams started roaming the land.

The three most frequent criticisms of the Eye, as Marnham notes, are that it is cruel and intrusive about people’s private lives; philistine; and anti-semitic. The second of these seems an irrelevant criticism: we hardly go to a satirical magazine for a constructive appreciation of the arts – would we prefer it if the paper started urging us to go to the latest Pinter play? And while ‘Pseuds’ Corner’ is marked by an inability to spot irony, it usually scores three bulls and one inner out of five.

To the charge of anti-semitism, Ingrams replies that the Eye is anti every other minority too, and that Jews have ‘become much too sensitive; they should be more tolerant of criticism, as they used to be.’ Quite what era Ingrams has in mind isn’t clear: presumably that blissful time not so long ago when golf clubs automatically excluded Jews from membership, when public schools operated a quota system (imagine what might happen if your school became ‘flooded’ with Jews – you might win a lot more university places for a start), and when Jewry on the whole ignored such smug persecutions and was grateful for what it received. But now, like homosexuals, they have got a bit uppity, and need to be reminded of this very English truth: that by toleration we do not mean equality. All that we are offering is the right not to be over-persecuted as long as you keep your heads down. The Eye’s anti-semitism – which is routine and fairly low-level, though none the less shameful – shouldn’t, of course, be fashionably restyled as anti-Zionism. It hardly seems a telling criticism of Israel’s West Bank policy to characterise a Weidenfeld-style publisher as ‘Snipcock’ in every issue.

The charge of cruelty has been put most succinctly by Clive James, who once rebuked Ingrams for letting his anonymous gossip columnist ‘fulfil a lifetime’s ambition, which is to tell dirty stories about the people he envies, and send their children crying home from school’. It’s a powerful phrase, though exactly how accurate is it? The more usual result of Grovel’s activities, after all, is enraged, embarrassed, blushing, tearful and sometimes divorcing parents. On the other hand, Ingrams’s reply – that if there are weeping children on the streets, it is the parents’ doing, not his – is clearly inadequate. It also has a familiar ring to it. Look, it’s not my fault: I only pulled the trigger. They shouldn’t have made the gun and the bullets in the first place. That laser night-sight? They certainly shouldn’t have sold it to me.

Three years ago, in a television interview, the doughty Robert McKenzie tried to extract from Ingrams the theoretical basis for his bedroom coverage. Ingrams began by declaring piously that he wouldn’t go into someone’s private life just for the sake of it: but added that with politicians ‘one cannot make a rigid distinction between private and public.’ So was he saying, McKenzie inquired, that adulterers should be barred from public office? No, but it was ‘highly relevant in assessing his personality if a man picks up women for one-night stands’. Ah, so what he was saying was that a promiscuous heterosexual should be barred from office? No, replied Ingrams, but ‘I think I would like to know about it all the same.’

Though Ingrams swiftly dived for cover with another unconvincing assertion that adultery wasn’t news in itself, this admission of honest prurience had slipped out (McKenzie was duly rewarded for his tenacity by being indirectly, but unequivocally, denounced as a homosexual in Grovel’s next column). In its original slang ‘the Eye’ denoted the Pinkerton Detective Agency, whose logo was an all-seeing eye. Nowadays, the term denotes Private Eye, whose logo, displayed on its first editorial page, is a burlesque version of Mr Punch tugging on his enormously erect phallus.

The popular press boosts its circulation by printing topless photographs of Koo Stark and then sneering at her morals. The Eye’s ethics are no more advanced: it’s just that their brand of hypocrisy is more AB. Consider the following statement: ‘Divorce and the break-up of a family is not the ideal subject for humour, as everybody knows that it is a grim business causing a great deal of unhappiness to everyone concerned.’ That was Ingrams, writing in the old-codger persona he employs for his Spectator television column, deploring the thematic inappropriateness of a new comedy series. Next day he was back at his editorial desk busy helping to destabilise a few marriages, and warming himself at the fire of other people’s purported adulteries.

Prurience? Hypocrisy? Might there perhaps be a simpler explanation for Ingrams’s position – that he doesn’t read his own magazine before it goes to press. His main sin, according to John Wells, is laziness: one reason why the paper still appears fortnightly is that it gives Ingrams one week off out of two. He might simply not bother to read everything that goes in nowadays. This attitude isn’t as rare in Fleet Street as might be imagined. I well remember Bruce Page telling me that one of the things he most enjoyed about editing the New Statesman was opening the paper on Thursdays and being surprised by what was in it. This was at a time when some of his readers were having the same reaction, the only difference being that they had paid for the surprise.

The Eye certainly has a wider spread of critics now than it used to – from which the magazine will doubtless conclude that it therefore has more work to do than ever. The Bunker mentality isn’t, however, always the most fruitful journalistic cast of mind (especially if it’s a Bunker with a pension fund). On the other hand, it’s also true that the group of people who complain most strongly about the Eye’s intrusiveness tends to overlap fairly closely with the group of people most likely to get busted for what the Eye regards as punishable offences. ‘Someone ought to run these guys out of Fleet Street,’ one of the magazine’s occasional victims complained to me the other day: ‘the only trouble is, who’s Mister Clean?’ Mister Clean by definition is someone that the Eye isn’t interested in.

And yet many of the people who bitch about the Eye – one distinguished Fleet Street editor mutters ‘Weimar Germany’ whenever the lampoon’s name is mentioned – still can’t stop reading it, still hold it in a sort of indignant affection. The newspaper-reading public is not, on the whole, a sentimental body, and rarely carries on reading a paper in homage to its earlier triumphs. Yet the Eye is very hard to give up. Partly, this is for the practical reason that it appears fortnightly (a lot of forgiveness can take place in two weeks); but partly, I suspect, it is out of a sort of nostalgia. Private Eye is the place where many newsprint addicts first learned their scepticism. Fleet Street was supplying, as it still is, a fairly homogeneous product when the Eye came along, broke all the rules and offered the reader a few truths (some of these were merely lies, of course: the magazine’s first major scoop was to reveal that President Kennedy had been previously married). It was with the Eye that many a newspaper reader first laid down his innocence; that first scar on the heart still throbs.

You don’t go to the Eye for anything as straightforward as opinions, and only partly for facts. You go to it for a received state of mind. Look, it says, the bishop farts just like the ploughboy; look, the country is being run by buffoons and incompetents. Once these lessons have been learnt, we hurry to apply them elsewhere (look, the Eye isn’t infallible; look, it’s possible to be a satirist and a prig at the same time). We also come to despise the learning of the lessons, and grow a little ashamed of our prelapsarian selves. We always knew that, we claim. But we didn’t.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.