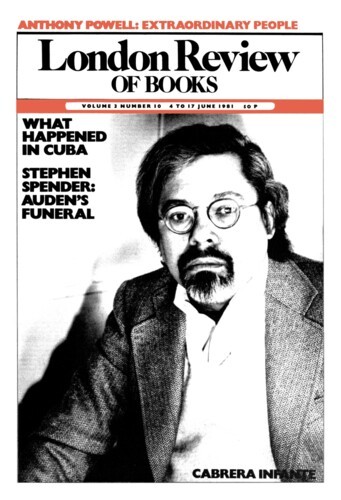

Cuba in 1961. The magazine Lunes de Revolution protests against the censorship of PM, a film about a black woman who sings boleros in Havana’s nighttown. The magazine is closed down forthwith, by that very revolution whose Mondays its title salutes. Lunes’ editor is a 32-year-old writer named Guillermo Cabrera Infante, and the director of the film is his brother, Saba Cabrera. Time-dissolve: four years pass. In 1965, Cabrera Infante, now Cuban Cultural Attaché in Belgium, is sacked (no reason given). Soon afterwards he leaves Cuba for good. Jump-cut to the present. Cabrera Infante is now living in London, almost completely ignored, like Elias Canetti before him, by the capital’s lovers of literature: however, his acclaimed novel Three Trapped Tigers has at last been published in England; a mere 13 years after its completion. In paperback, too: a snip at under three pounds. Hurry while stocks last.

By the standards of Robben Island or the gulags, Cabrera Infante’s consignment to limbo is fairly mild stuff, and my reasons for giving the above history are not political but literary. Firstly, of course, the novel in question is without any doubt one of the most inventive and influential products of the Latin American ‘new wave’, and can stand comparison with the richest treasures in that EI Dorado of modern fiction. Secondly, it is a novel born of the cinema, whose narrative techniques – track, pan, zoom, jump-cut, flashback, flash forward – are all present in these pages, and whose stars (Ava, Groucho, Andy Hardy) loom large in the mental landscape of its own cast of thousands. The novel’s first word is ‘Showtime!’ and its stars are almost all unknowns: drummers, singers, actors, writers and other Cuban heels throng its now bright, now shadowed streets and dives. Even the heroine of the banned film PM is reincarnated here as the great black whale of a singer, ‘La’ Estrella, a warbling Moby Dick or, to allow this review to become infected by Cabrera’s advanced pun-ophilia, Moby Pussy.

And there is a third reason. When this novel, under the title Vista del Amanecer en le Tropica (Vision of Dawn in the Tropics), was awarded the Biblioteca Breve Prize in Barcelona in 1964, ‘it was,’ to quote Cabrera Infante’s own words, ‘sad to say, very much a socialist realist novel,’ in which the nightworld of Batista’s Havana was counterpointed with the story of a group of revolutionaries. ‘It contrasted,’ Cabrera says, ‘exemplary positive lives with exemplary negative ones.’ But as his disillusion with the revolution increased, Cabrera Infante revised his novel, cutting out the noble guerrilleros and leaving us with this swarming, vivid pyrotechnic portrait of the boozy underbelly of a city, a portrait which has no lessons to teach us other than absolutely crucial ones: about friendship, men, women, memory, music and language. It is also extremely funny – as when describing the wholly fictitious inventions of one of the central group of characters, Rine Leal:

– Meanwhile he invents other inventions. The headless and pointless knife, fr. xmpl. Not a pointless invention, believe me.

– Or the windproof candle.

– A brilliant idea.

– Luminous. Simple, too ... every candle has the words Don’t light printed on it in red ink.

– Another invention of genius was his urban condom ...

What is this crazy book actually about? Well, this is what passes for its plot: the photographer Codac tells the story of the rise and fall of La Estrella, the singer who can make garbage sound like nectar; another character, Eribo or Ribot, an advertising writer by day and a drummer by night, unsuccessfully pursues the young heiress Vivian Smith-Corona Alvarez de Real; a large number of sensationally beautiful women, Magalena and Irenita and Livia and Laura and Mirtila and especially the super-luscious Cuba Venegas, strut their stuff; it seems remarkably easy to fondle their breasts but almost impossible to get beyond that stage. Cuba Venegas was born Gloria Perez before making it as a model and inspiring a friend of her mother’s to write furiously (of Cuba’s picture in an ad): ‘the words are like a hand and the letters like fingers and they go all around her naikid body and where it says dig it’s like a middle finger this word going into your daughter Gloria Perez.’

And in the long, long section which forms the last third of the book two old buddies, Silvestre, the movie-freak and writer, and Arsenio Cué, well-known TV actor and dandy, go on a long bender, talk and argue and joke, pick up a Beba and a Magalena, fail to get further than breast fondling, and entirely miss the point about one another: that Cué has decided to go off and join Castro and his guerrillas (to which revelation Silvestre replies: ‘Brother, you’re drunk’), and that Silvestre has decided to get married (Cué’s response: ‘You’re about to make the first really irreparable mistake in your life’).

So much for the plot. (Warning: this review is about to go out of control.) What actually matters in Three Trapped Tigers is words, language, literature, words. Take the title. Originally, in the Cuban, they were three sad tigers, Tres tristes tigres, the beginning of a tongue-twister. For Cabrera, phonetics always come before meaning (correction: meaning is to be found in phonetic associations), and so the English title twists the sense in order to continue twisting the tongue. Very right and improper. Then there is the matter of the huge number of other writers whose influence must be acknowledged: Cabrera Infante calls them, reverently, Fuckner and Shame’s Choice. (He is less kind to Stephen Spent and Green Grams, who wrote, as of course you know, Travels with my Cant.) Which brings us to the novel’s most significant character, a sort of genius at torturing language called Bustrofedon, who scarcely appears in the story at all, of whom we first hear when he’s dying, but who largely dominates the thoughts of all the Silvestres and Arsenios and Codacs he leaves behind him. This Bustromaniac (who is keen on the bustrofication of words) gives us the Death of Trotsky as described by seven Cuban writers – a set of parodies whose point is that all the writers described are so pickled in Literature that they can’t take up their pens without trying to wow us with their erudition. Three Trapped Tigers, like Bustrofedon’s whole life, is dedicated to a full frontal assault on the notion of Literature as Art. It gives us nonsense verses, a black page, a page which says nothing but blen blen blen, a page which has to be read in the mirror: Sterne stuff. But it also gives us Bustrolists of ‘words that read differently in the mirror’: Live/evil, drab/bard, Dog/God; and the Confessions of a Cuban Opinion Eater; and How to kill an elephant: aboriginal method ... the reviewer is beginning to cackle hysterically at this point, and has decided to present his opinion in the form of puns, thus: ‘The Havana night may be dark and full of Zorro’s but Joyce cometh in the morning.’ Or: ‘Despite the myriad influences, Cabrera Infante certainly paddles his own Queneau.’

Also necessary is a list of Subjects Impossible to Discuss in this Notice for Reasons of Space. These are: how the male characters, trapped in macho, their obsession with style, and their determination to act as though none of them actually needed a job, are caged, boxed in, stifled by their invented selves: trapped by trying to be tigers. Which leads us to the important theme of masturbation, which Cabrera Infante calls ‘playing a private part’ and why all the characters keep having night-mares; and when they find time to have them because none of them appears ever to go to sleep; and why the TV producer shot Arsenio Cué three times – in the chest, the shoulder and the stomach. And now I ought to include a list of lists impossible to include for reasons of space, but must omit it for reasons of space.

Three Trapped Tigers has been translated into electric English by Donald Gardner and Suzanne Jill Levine, in collaboration with the author. I don’t know why any human beings should wish to attempt a task as difficult as this – perhaps because it was there; at any rate, they have performed the translator’s most invaluable function, acting as linguistic jump-leads and enabling us to recharge the batteries of our played-out literature from the power source that is the imagination of Guillermo Cabrera Infante.

They tell me the English are particularly reluctant to buy translations of ‘foreign’ novels, but just in case superlatives will help to sell a few extra copies, I provide the following selection (choose to taste): TTT is the most exciting/sexiest/funniest/noisiest/most imaginative/most evocative novel anyone, even an Englishman, could wish to read. It’s a Cuba Libre of a book, a daiquiri cocktail, or perhaps a literary version of the drink which Silvestre calls ‘a mojito ... this Cuban mint julep which is a metaphor of Cuba. Water, vegetation, sugar (brown), rum and artificial cold. Mix and strain, stir till glass frosts, spin rim in sugar (white). Serves seven (million) people.’ Cheers.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.