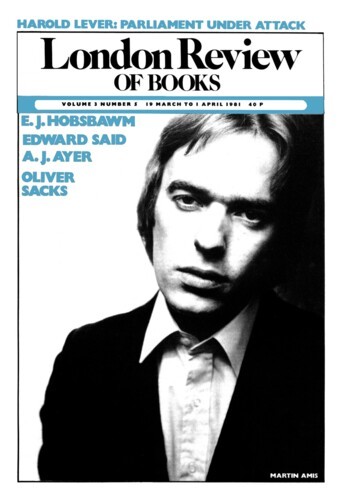

Since Success, Martin Amis has been involved in a spectacular case of alleged plagiarism. As the apparently aggrieved author, Amis showed himself notably unresentful and unlitigious. Indeed, he took the offence as an occasion to ruminate good-naturedly on the oddities of literary ‘borrowing’. It’s relevant to bring this up since Other People depends very largely on a trick which is usually thought to be someone else’s trademark.

First, to describe the novel. The narrative follows a heroine who has woken in hospital (‘a white room’) lacking all long- and short-term memory. The amnesiac gimmick is common enough in SF and thriller fiction (Other People is subtitled ‘A Mystery Story’, though the blurb somewhat nervously qualifies the description with the term ‘metaphysical’). But Amis is less concerned with reconstituting the mysterious past of Mary Lamb (as she arbitrarily calls herself) than with exploiting her as a centre of deranged consciousness. For Mary the common world is defamiliarised. Thus, for instance, she tackles the telephone:

Mary had watched people use the telephone several times and was pretty confident she could handle it. The bandy, glistening dumb-bell was heavier than she expected. But she had expected the call: she knew who this must be.

‘Yes?’ said Mary.

A thin voice started calling. Telephones were clearly less efficient instruments of communication than people let on. For instance, you could hardly hear the other person and they could hardly hear you.

‘I can’t hear. What?’ said Mary.

Then she heard, in an angry whine, ‘I said turn it the other way up’.

Mary is a home-grown version of Craig Raine’s Martian, for whom the quotidian and domestic props of life are rendered bafflingly alien and wonderful:

In homes, a haunted apparatus sleeps,

That snores when you pick it up.

If the ghost cries, they carry it

To their lips and soothe it to sleep

With sounds. And yet, they wake it up

Deliberately, by tickling with a finger.

Raine and Amis are of the same generation (young), and of the same university, and their careers in literary journalism have intertwined. They are held to belong to a coterie which has been termed – embarrassingly for them, doubtless – the New Oxford Wits. Given a degree of literary fraternity, there is no reason why Amis should not have experimented in fiction with Raine’s Martian perspective. The law allows no copyright in technique or device, any more than in ideas. (Jacob Epstein’s offence, allegedly, was to use forms of wording from The Rachel Papers.) The danger is that in this novel, with its elaborated and repeated effect, Amis seems, as Raine can occasionally seem, something of a one-trick pony.

Other People has a plot of kinds. Mary picks up with and is picked up by various wrong sets, from the criminal to the swinging. She has Candy-like adventures, as she discovers what the different holes in her body are for. In the last brief section the heroine recovers consciousness of her original identity and history. In some very enigmatic fashion, the facts about her would-be saviour, Detective Prince, and her would-be murderer, Mr Wrong, are sorted out. There’s an Incident at Owl Creek-like ending in which Mary may be executed, or reborn, or returned by time-loop to the novel’s opening situation. Other People, this is to say, does not easily give up its secret – at least not to me. Amis’s cleverness has always been of the kind which makes the clodhopping reader feel he is having rings run round him. As a sustained exercise in ostranenie, the Russian Formalist term which translates uneasily as ‘making strange’, Other People is virtuosic. As a development in Amis’s rapidly unfolding fiction-writing career (only one of his careers, incidentally), it’s very unexpected. As a mystery story, it’s very mysterious. Such is Amis’s authority, already, in modern English fiction that it will be taken very seriously.

The Magic Glass is propelled our way by a back-coverful of pre-publication puff: ‘really marvellous’ (Colin Wilson), ‘wickedly funny’ (A.S. Byatt), ‘very nourishing entertainment’ (Dame Rebecca West). The manuscript’s progress through the hands of less enthusiastic publishers has been recorded in various gossip columns. Anne Smith, editor of the Literary Review, is a canny publicist for herself and her journal. Now, at last, we have this already much-read work to review.

The Magic Glass is transparently a version of the author’s childhood, some thirty years ago in Fife (here ‘Skelf’). Before evaluating Smith’s particular achievement in her first novel, it’s worth going a little into the general question of why Lowland Scots, as different in pedigree as David Daiches, the film-maker Bill Douglas, Jimmy Boyle and Anne Smith, should be so determined to rake over and publicly display their childhoods (all more or less deprived childhoods, though in Daiches’ case less so from poverty than from an austerely Judaist upbringing). To take a topical example: what distinguishes A Sense of Freedom from the paid confessions of other latterday Newgate heroes like Alfie Hinds or John McVicar is the intensely narcissistic attention Boyle turns on his early days in the Gorbals. Whereas McVicar perfunctorily stereotypes himself as the grammar-school boy perverted by his ‘milieu’ (fellow-con Charles Richardson’s Open University-speak), Boyle creates an extraordinarily vivid and well-written portrait of the criminal as a young urchin. It is done without nostalgia, posing or special pleading. The childhood chapters are far and away the best thing in A Sense of Freedom. Jeremy Isaacs saw fit to cut them, however, together with the Barlinnie redemption, in his tendentious television version, leaving nothing for the gawpers but the hard man’s sado-masochistic feats in and behind bars. So, too, the first volume of Daiches’ autobiography – Two Lives: A Jewish Childhood in Edinburgh – is much more powerful than its sequels. And for all the superior literary technique, Daiches’ has the same quality of crystalline, unsentimental objectivity as Boyle’s account. As far as I know, Douglas hasn’t made films on other themes than ‘my childhood’. If he has or does, I’d guarantee their inferiority to the trilogy.

Since Wordsworth, identifying the child as father to the man has been a standard literary exercise, from The Prelude’s great unfinished Gothic cathedral, through the Bildungsromane of the 19th century to Graham Greene’s baize door. Since the popularisation of Freud, there can have been few Penguin-carrying adults who have not, however casually, investigated their ‘formative’ years. But with Douglas, Daiches, Boyle (and Smith, incidentally) there is a difference. For them, there is no continuity drawn between childhood and mature states of being. What these autobiographical works convey is a sense of wonder at the impossibility of ever finding a logical connection between the original street Arab (or Morningside Jew, in Daiches’ case) and the sculptor, the Professor of English, the darling of the BFI, the editor of the Literary Review. At some point the string breaks and the chronicler is left in the labyrinth. The only sustainable attitude for the autobiographer is one of wonder, or disbelief that he was ever really like this. The disbelief is rationalised by a mechanism implicit in Daiches’ title, Two Lives. (The notion of a division is a feature of Daiches’ contribution to the debate on the subject of the Scottish psyche and culture, and the issue is dealt with from a different angle in Karl Miller’s Cockburn’s Millennium.) The sensitive Scot, this is to suggest, makes sense of the change which has occurred between himself then and himself now by assuming disruptions, dualisms.

It’s not so much that childhood is lost as that it happens to someone else. To return to Boyle: it is surely only in terms of an inversion of the Jekyll and Hyde myth that one can credit his story. The change from excrement-smeared, hammer-scarred thug to artist is incomprehensible as ‘development’ or ‘reform’. It is entirely different from the educational escalator which turned McVicar into a postgraduate sociology student at Leicester University.

The sense of amputation from their own childhoods in these autobiographers is partly explained by the fact that some of them have taken Dr Johnson’s recommended route, and found themselves alienated by place as well as time from what they originally were. Scots are never home – so the soggy, sentimental myth-message about Scottish soldiers, high roads, low roads and longest miles back would tell us. The only Scot in Hardy’s fiction is called Farfrae – it is his ethnic destiny to be far from home, a native even less capable of return than Clym Yeobright.

Other émigrés and déracinés seem to manage it better. Raymond Williams’s semi-autobiographical (I assume) Border Country, for instance, is concerned with the final integration of the hero’s metropolitan present with his working-class Welsh childhood. The novel concludes, homiletically, with the following exchange:

‘It was bound to be a difficult journey.’

‘Yes certainly. Only now it seems like the end of exile. Not going back, but the feeling of exile ending. For the distance is measured, and that is what matters. By measuring the distance, we come home.’

Such measuring, such homecoming, would often seem to elude the Scot.

The Magic Glass, then, is not concerned with putting the whole self together. Rather it slices off a childhood, and leaves it disconnected, a preparation for nothing. There remains, however, an uneasiness, as if the author felt obliged to offer something more in the way of a portrait of the editor as a young woman. The heroine of the novel, Stella, is ostensibly the product of her class and her culturally impoverished background. In terms of what we are shown of her abilities, there is no evidence that she will transcend it to become anything more than a clerkess in Edinburgh; more likely, she will pass to child-bearing drudgery like her mother before her. As she is presented, there is nothing special about Stella. Yet, paradoxically, we are evidently meant to apprehend that she has a special destiny waiting for her. The title, and epigraph, link her with that superior young lady, Alice. Stella’s favourite reading is Grimm, from which we are presumably intended to infer that she is an ugly duckling. But just how the metamorphosis will happen is left obscure. The novel ends with her returning to Skelf with the ever-pregnant mother, throwing, for luck, a none too optimistic penny over the Forth Bridge.

Smith’s novel can only be called slight. It offers a series of stops on the way from Stella’s birth to her puberty. The chosen episodes are snapshots, sometimes randomly taken, and mocked by grandiloquent chapter titles (‘A Star is Born’, ‘Mighty Like a Rose’). The sequence records her birth inter faeces (her mother has taken an ill-timed overdose of salts); her ungrateful father, desperate for a ‘laddie’, names her after the passing milkman’s horse; the narrative jumps seven years to the heroine’s running away to her sympathetic grandmother; grandmother dies. The third chapter moves to a couple of years later, and Sunday school: Stella steals from the church collection. Now pubescent, she is seduced spiritually by the Salvation Army and felt up by a dirty old man on her paper round. Another jump takes us to passionate friendship with a girl from the local orphanage. She visits the music hall, playing gooseberry on her older sister, Sheila. In the final episode, her father gets a treble up, and stands Stella and her mother a day in Edinburgh.

What appeals most in Smith’s novel is its cocky toughness. It is frankly xenophobic in a familiar Scottish working-class tradition. ‘God,’ Stella comes to believe, ‘was middle-class and possibly even English.’ That taint is enough to turn her off religion for good. Her precocious interest in ‘women poofs’ hints that Stella’s unglimpsed future may lead her to some kind of post-1960s sexual liberation. And running through the novel, for all the sensitivity of its conception, is a kailyard crudeness of diction. Stella’s bosom friend is described in a style which would find the word ‘bosom’ screechingly hilarious:

The only thing she and Roberta had in common was tits: in every other respect they were ill matched. Stella was dark and thin and mercurial. Roberta was the slow strapping fair peasant her surname suggests: Roberta McLusty... They had nicknamed her ‘Bubbles’ because of the two bright green tube-like snotters that glinted perpetually under her nostrils and occasionally, for no apparent reason, inflated themselves, but never burst.

I suspect that such emetic passages are designed to épater l’Anglais, and mock their well-mannered ‘really marvellous’, ‘wickedly funny’, ‘very nourishing entertainment’, and reviews like this one.

The Book of Ebenezer Le Page has its points of resemblance to Smith’s novel. It is the story of an undramatic life, narrated by an 80-year-old Guernseyman. The son of a quarry worker, Ebenezer has modestly risen to the condition of self-employed ‘grower and fisher’. He never leaves the island, and what wisdom he gains is circumscribed in provinciality.

Much happens around Guernsey between 1870 and 1960, but the island remains on the edge of history. The hero, too, has a quiet, marginal existence. His best friend Jim is killed in the First World War; his next best friend, Raymond, is blown up in the second by a German mine while injudiciously walking out of bounds. Ebenezer is crossed in love by a coquette and comically persecuted in later life by a widow with a wooden leg. He never marries. During the Occupation he engages in some minor and random resistance, and some equally random fraternising with the enemy. Generally, he keeps himself to himself, and becomes a thing of local curiosity – ‘the funny old man’. He makes a pot of money, which he buries in the garden of his stone-built house: he expects the house to last for ever since ‘it cost a hundred pounds; and that’s a lot of money.’ The last, mildly fulfilling act of a featureless life is the discovery of an heir, representative of the true Guernsey spirit, to whom he can leave his little wealth. Ebenezer’s strongest feelings are insular and reflexive: hatred for Jersey and for the English who have prostituted his island into a resort-cum-tax-haven-cum-tomato-factory. In one of his shrewder moments he observes that it was certainly the occupation which ruined Guernsey – ‘the English occupation’.

The main stress in the novel is on Ebenezer’s monolithic psychic continuity in a fluxile, disintegrating society. The picture that emerges is rather like the linear vision Vonnegut credits the aliens with in Slaughterhouse Five: ‘Tralfamodorians don’t see human beings as two-legged creatures. They see them as great millipedes – with babies’ legs at one end and old people’s legs at the other.’ Just such a millipede is Ebenezer Le Page. The incursion of patois is slightly invigorating, but four hundred pages of literary primitivism is a very lowering diet.

What renders this book at all interesting is the background to its posthumous publication. As John Fowles tells us in a preface, Gerald Edwards was born in 1899 on Guernsey. He was the son of a quarry owner, a well-educated scholarship boy who saw service in the First World War and then took a degree at Bristol University. In the 1920s he worked in the WEA and was obscurely connected with D.H. and Frieda Lawrence. It seems that he wrote, going so far as to describe himself as ‘author’ by profession. What he wrote cannot be traced. From the time of the break-up of his marriage in 1933 to his reunion (unsatisfactory) with his surviving family thirty years later, Edwards’s life is utterly mysterious. No more can be retrieved than that he was a minor civil servant, probably living around London. From his retirement in 1960 until his death in 1976, it is known that he lived as a recluse in Weymouth. The spot was chosen, as Fowles observes, for its being the closest he could get to Guernsey. The island’s inflated property rates made retirement there impossible, even if he could have claimed the islander’s privilege of lower house prices. Ebenezer Le Page is the only book Edwards wrote, and it was everywhere rejected in the early 1970s, when friends prevailed on him to show it to London publishers. He died as he lived, an unsuccessful author and an expatriate Guernseyman.

Death is one of the more effective publicity stunts which the author has at his disposal. Yukio Mishima did his sales no end of good by ritually disembowelling himself in front of the world’s press cameras. In a quieter way, it is hard to see how this work could have merited print, had it not been for the interesting failures of Edwards’s life, and their presentation as a lead-in to the novel. We might see it as an expression of pathetic yearning, of return denied. As something less than a genius and clearly no flier in his profession, he could never amass the capital or pension to settle there in later life. What this work would seem to conclude is that the only way the native can return is never to have gone in the first place.

Sharpe’s Eagle is representative of a steadily best-selling genre seldom regarded by criticism, although it has had at least one respectable practitioner in C.S. Forester. Typically, these works form multi-volume sequences around the fortunes of a military or naval character, who ages and rises in rank from instalment to instalment. The settings are historical – more often than not the Napoleonic wars (English Francophobia, incidentally, may be one of the deeper motivations making for their popularity). Front-line war is the first interest of this fiction, steamy romance a usual sub-plot. Invariably it is ostentatiously ‘researched’, and carries a heavy cargo of historical technicality about such things as brigantines, forming a square, how to load and fire a flintlock. The market leader is without question Dudley Pope, whose ‘Ramage’ series is coming up to its 12th instalment. Pope claims an apostolic relation to ‘CSF’ himself. (Apparently, when Hornblower made admiral and was coming up for retirement, the master suggested to Pope that he create a successor.) Nevertheless, I would take the genre’s progenitor to be the less estimable Dennis Wheatley, with his Roger Brook saga.

It’s tempting to think of these fictional sausage strings as the male equivalent of Mills and Boon romances – ‘books that please’, kleenex for the mind. There are, however, important differences. For one thing, Dudley Pope and the apprentice Bernard Cornwell are not ashamed to write under their own names. And both have impressive credentials: Pope is a distinguished naval historian, Cornwell rose to be head of BBC Television’s Current Affairs Department in Northern Ireland.

For all their insignificance to most reviewers, there is clearly big money involved in these sequence-novels (Sharpe’s Eagle, for instance, is ‘© Rifleman Productions Ltd’, which argues a confidently commercial approach). From the selling point of view, the launch-volume is all-important. Once it has caught on, brand-loyalty makes it a repeat-order affair – the kind of business the book trade likes best. Pope clearly has his public hooked and his rhythm right. Indeed, in July 1981 he intends to partner ‘Ramage’ with a ‘Buccaneer’ series. Set in the Spanish Main, in the 17th century, it will follow the fortunes of sea-dog Ned Yorke (this is home territory for Pope, who lives in the West Indies on board the yacht Ramage).

Sharpe’s Eagle is a launch novel. The hero is Lieutenant Richard Sharpe, commander of an élite rifleman company foraging, skirmishing and sometimes battling in the Peninsular War. The first instalment takes us to 1809. The whole cycle is designed to follow Sharpe’s career for the next six years to Waterloo and, presumably, death or glory. Sharpe, as we first encounter him, is a 31-year-old veteran, risen from the ranks. He has two sorts of enemies: upper-class career officers who purchase their promotion over his head and the French, who at least give him a fair fight. Having fallen foul of his hidebound snob of a CO, Sharpe sets himself the task of winning a French eagle standard in battle, so as to secure himself against enemies in high places. He succeeds, on Talavera’s field. (The night before he skewers a fellow – but aristocratic – officer, who has presumed to rape his Spanish enamorada, Josefina.) Sharpe ends the novel triumphant. Doubtless trials and ordeals are to come, if the targeted middle-aged male readership takes to the new line of goods. They may well do so. Sharpe’s Eagle is perhaps too solidly and obviously researched, and the hero lacks any of Hornblower’s quirkiness: but Cornwell’s novel is very efficiently written.

The XPD of Deighton’s enigmatic title should be glossed as ‘expedient demise’. His latest blockbuster is based on the factoid that there are three unaccounted-for days in Churchill’s and Hitler’s movements in June 1940. What happened, we are to believe, is that the supremos met in France where Churchill offered craven surrender terms, involving the carve-up of the Empire, sovereignty of the seas, and vast reparations. The record of the exchange – the so-called ‘Hitler Minutes’ – is dynamite. It must be suppressed at all costs and for ever. A decently off-stage Mrs Thatcher goes puce with rage at the thought of its being released: ‘It would mean the end of the Tory party.’ Any uncleared person who does find out the secret has his dossier stamped XPD.

As it happens, the German draft of the Hitler Minutes has come into the possession of a gang of American Army looters, who scooped them up with other goodies at the end of the war. Now their ill-founded Swiss bank has gone bust and (very implausibly) they are hawking the document around Hollywood film-makers. This sets the KGB, MI6, the CIA and ‘Siegfried’ (a Nazi revanchist society) on their trail.

XPD belongs firmly in the ‘secret history of the war’ genre. (Genetically it seems a mixture of The Mittenwald Syndicate, The Goering Testament and The Eagle has landed.) As with others of its kind, its main contention is the folkloristic one that the real truth of history has been covered up, that secret fortunes have been made, and that it only needs the removal of one card to bring the whole thing tumbling down. In the 18 years since The Ipcress File Deighton has shown himself to be the most protean of British best-sellers. His best writing seems to have been done with Cape. Rather surprisingly, this house was a nursery for the best secret agent fiction of the 1960s. Deighton is now with Hutchinson, where he shares top billing with Forsyth. Indeed he seems to be contesting it. XPD borrows many of Forsyth’s tricks: the rapidly changed international setting, the dead-pan reportage style, the cut-out characters, the stress on insider’s knowledge and terminology, familiar to the author, alien to the average reader. This Forsythian XPD I take to be something of a comedown from the earlier sequence, which had a genuinely engaging anti-hero. It is an even bigger come-down from Bomber, probably the best and certainly the most accurate popular novel about the Second World War in the air. Compared with these, XPD is a routine and nerveless performance, though such is the potency of Deighton’s name that the novel is bound to sell well. (I notice that some London bookshops are so eager to get at the sales action that they are selling XPD as I write, some two weeks before the publication date.)

For all its diversity, there are certain core elements in Deighton’s fiction. His novels all betray the other ranks’ hatred of the commanding-officer class. It is the front-line men, agents, pilots, detectives, who are admirable. Another core clement is Deighton’s urge to demythologise. This is at its most aggressive in his recent work of history, Fighter, which presumes to dismantle the Churchillian myths about the heroism of the Few. His last novel, SS-GB, goes a step further: an alternative universe novel, it fantasises a Nazi victory and occupation in 1940 (Churchill – against whom Deighton seems to have something personal – is shot). Both the bolshy and the debunking aspects of Deighton are on display in XPD, which features a very slimy Director General of MI6 and seeks to convert Churchill’s image from bulldog to whipped cur. There’s clearly a lot of writing energy and creative disgruntlement left in Deighton. I hope it produces better things than XPD.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.