This book suggests how an odd mixture of Hungarian nerve, social bluff and show-business instinct once commanded the British cinema. In Michael Korda’s telling, however, the panorama of picture-making is not always alight with understanding or information. The author may have been born on the night in 1933 when his uncle Alexander Korda’s first great success, The Private Life of Henry VIII, opened, and that could have made Michael a good-luck charm in Alex’s eyes. But Michael is neither a film buff nor a historian of the movies. He is, instead, that vital figure in the picture business, a nephew, half-English, half-American, and in his dreams entirely Hungarian. He grew up enthralled by his uncle Alex: he can only provide a fond and rather vague sketch of his father, Vincent, and a perfunctory one of his other uncle, Zoltan. The lives of the title are not three but two: uncle and nephew, the last tycoon and the ardent imitator. The extraordinary interest and appeal of this book spring from the way Michael Korda always wanted to be his own uncle.

When Scott Fitzgerald wrote The Last Tycoon he invented the original of Michael Korda: Cecilia Brady he called her, a girl dried out on knowingness who was ‘going to write my memoirs once, The Producer’s Daughter, but at 18 years you never quite get around to anything like that.’ Fitzgerald wanted to make his Culver City child bored with the place: ‘My father was in the picture business as another man might be in cotton or steel, and I took it tranquilly.’ But long before he died, with the novel unfinished, he had poured his own bitter love of movies into Cecilia.

Michael Korda is the genuine article, drawn to power but taking movies for granted. He never bothers to say or notice how silly and delightful many of Alexander Korda’s films were. He is not very interested in the argument as to whether Korda achieved a unique, bold excellence in British cinema or whether what he did amounted merely to a vulgar and forlorn attempt to make another Hollywood at Denham which entailed a disastrous inflation of budgets, script material and entrepreneurial attitudes. Whatever the blurb and the reviews say, Charmed Lives is not crammed with fresh anecdotes about picture-making: it has very few scenes of on-set life, and nothing to match Fitzgerald’s devoted record of a day in Monroe Stahr’s ruthless progress.

What it does have is the reverential nostalgia and the uncritical feasting on glamour promised by an opening sentence that echoes the clipped emotionalism of Fitzgerald’s rear-view sensibility: ‘It seemed to me when I was young that the three Korda brothers led charmed lives.’ Michael was the son of Vincent Korda, a painter willed into movie art director by Alex’s urging, and of Gertrude Musgrove, an actress. As an infant, in London, Michael ‘was often allowed to sit at the dinner table until midnight, eating strudel ... while my father and his friends argued in Hungarian, waiting for the magic moment when my mother, breathless, beautiful and smelling of Schiaparelli and grease paint, returned home from the theatre and instantly became the centre of attention’.

The gorgeous past is held in the nostrils, and it was not long before Michael could recognise Uncle Alex’s Montechristo cigars. The most flamboyant impresario that the British picture industry had known, Alex was the only man who had ever conquered the American market (with Henry VIII), and the conjurer who persuaded the Prudential to invest in a film studio. He had got out of Hungary, narrowly avoiding execution by the Horthyists. He had taken his first actress wife, Maria, to Hollywood, failed and left her there. England may have been his last chance, and it was not the most likely place for Korda to flourish. But it still had an empire, and enough appreciation of stylish emperors. Alex believed in the splendour and production values of English history as much as his new friend, Churchill. His pictures were Gay Hussar and high Tory. In time, he opened offices in America ample enough to hide the coming and going of the British Secret Service. At a crucial moment, 1941, he made That Hamilton Woman, the Nelson-Emma story, with Olivier and Vivien Leigh, and a rousing anti-fascist speech which Churchill may have written for the film.

In 1942 he was knighted, the first time that honour had ever gone to a film-maker; and why should the accolade not pause over a grey Hungarian head, born Sandor Laszlo Kellner? Years later, when the Earl Marshal was short of coaches for a coronation, Alex went to his props department and found a dozen assorted broughams for the state occasion. He could be as English as Nelson or the Duke of Norfolk because he saw that Englishness was only an act to conceal shyness, and one that was nearing the end of its run.

Alex had carried Vincent and Zoltan with him, as well as a caravan of other Hungarian talents. He dominated the family, organising lives and providing careers. With the coming of war, Vincent took his wife and son to Los Angeles, where Alex was intent on proving the stardom of Merle Oberon, his second wife. But like a true patriot and knight, Alex went back to England, taking Vincent with him. It was a separation for Michael’s parents that would lead to divorce. The boy remained in America with his mother. This book might never have been written but for Uncle Alex’s summary decision, in 1947, that Michael was wretchedly ignorant and in need of a European education.

And so Michael returned to England, gave up his mother for boarding-school, all at the irresistible behest of Alex. It was the perfect age to re-enounter a man who lived in a flat on the roof of Claridge’s, who knew everyone, believed in the necessity of luxury, and who seemed witty, wise and rich. Michael was taught good tailoring, the rhythm of paradox and the thinness of ice. Alex was also a man playing the scoundrel, a gypsy Falstaff who told his 13-year-old nephew that if he wanted to make his way in the world he should always go to the best hotels with the most beautiful women, save his cash for tipping, charge everything else and wait for someone to give him money.

It may look like gambling, lies, and self-destruction tomorrow. But once upon a time, the Korda boys had been ambitious and only modestly provided for in the plains of rural Hungary. Alex’s world was disintegrating already in 1947. The government was trying to help him save the film industry, but the effort was as doomed as the idea of British Lion. The nephew saw only a magnificent manager and a picaresque entourage. Film rights were bought before lunch and sold again at dinner for a huge profit – no wonder the meals were so rich. It is a world of Dom Perignon and caviar, a yacht off Antibes and a limousine with a faithful chauffeur waiting at the door.

Of course, there is much more in the book. Michael Korda has conscientiously traced the years before his birth, but he tells us that the English Alex was never very talkative about those times, and Michael never knew more than a little Hungarian. Periodically, he tries to explain the problems that faced the English film industry, and he does mention most of the films his uncle made. But the first part of the book admits to being in ‘Long Shot’, and it often feels second-hand or dutiful.

‘Close-Up’ begins on page 185, and it is worth waiting for; nor could it have been appreciated without the background. At the same time, one can imagine Alex reading this part of the book and recognising the basis for a movie. Its story may be rooted in fact, but it has the shape of fiction. The reason is that as Michael went through his European schooling, ending up at Magdalen and the Financial Times, so his uncle took a new young wife. On one visit to the South of France, Michael met an unfamiliar young woman wearing a sun tan and one of Alex’s cream silk shirts. She was Alexa Boycun, a Canadian. Later on, Michael guessed that she had come into his uncle’s view as a sultry model in some pin-up pictures taken by one of his many Hungarian hangers on. Alex was in his late fifties when he made Alexa, Lady Korda. She was in her early twenties, about five years older than Michael.

What follows is the discreet but engaging story of an uneasy triangle in which all the parties come into sharp life. Alex should not have married again. He knew it, but he was lonely and trapped in his own axioms. Alexa did want money and a position, and she knew that many saw her as a fortune-hunter. And Michael proved a more natural playmate for Alexa than the husband who knew his heart was failing. The nephew and his aunt went out together on trips and pranks. Michael wanted to sleep with her, but Alexa told him that was only because he wanted to be Alex. Then once when she was bored she whisked Michael away from London to see a football match in Switzerland. Scandal was covered up. A grave Alex forgave his nephew, but told him to go back to Oxford and concentrate on his studies. It was the last time Michael ever saw him. Alexander Korda died in 1956. In that year, amid the romantic but brutal confusion of the Budapest uprising, Michael made his first visit to Hungary in search of the native base and inspiration of the dazzling uncle.

‘Final Cut’, the third part of the book, is brief, sad but funny, as Alex’s estate is disputed by various wives and relatives. It has Alexa telling Michael that he always saw his uncle in the best light, that the old man was restless, difficult and unhappy, a flesh-and-blood person who must have hurt and offended many people in his time.

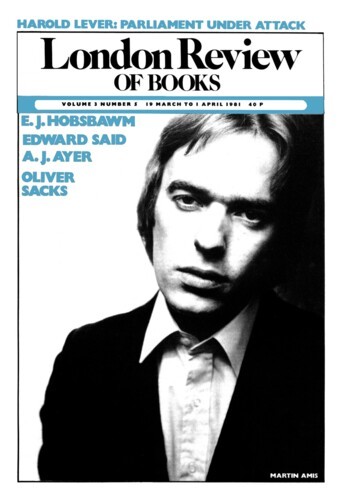

Who knows how thoroughly Michael Korda has yielded to common sense? Charmed Lives never admits a darker side to Alex, and it never complains about what must have been an unstable childhood. Its richest strain is the gratitude Michael feels for such hectic opportunity. The boy learned from the uncle: Michael Korda went on to be a leading American publisher and the author of Male Chauvinism!, Power! and Success!. So many exclamation-marks remind us of Hungarian accents. His own face adorns the jacket flap, a smiling wolf not far from his uncle as a young pirate. Charmed Lives is one of the best books about the movies because it is a personal memoir in which the picture business takes second place to the ideas of success and living well. Its author and its chief subject were equally captivated by the masquerades of photography and romance, and by the strategy of going beyond your resources at the best hotels. Much of the book is set in England, where such Hary Janos manners seem especially cheeky. But Charmed Lives grasps the outrageous gall and enterprise that still succeed in Hollywood, and in the end it abides by the dream that within every boisterous tycoon there is a more enigmatic, sensitive spirit – ‘suave, successful, charming and faintly melancholy’. Michael Korda remains pledged to the spell, like Orson Welles believing in the mystery of Charles Foster Kane, or Fitzgerald cherishing Gatsby.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.