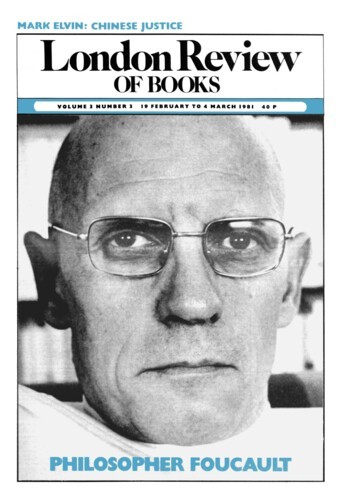

Start at the back: with the photograph. Traditionally, author’s vanity and publisher’s lethargy combine to make a writer look much younger than he is. Truman Capote’s portrait does the opposite, and for a particular reason. Study recent press photographs of Mr Capote, or those published last year in Andy Warhol’s Exposures, and what do you see? A plump, jowly figure in the flush of vital middle age, capering into Studio 54 on the languid arm of a heavily beringed dress designer: a man, it appears, of active sensuality verging on self-indulgence. Now compare the Irving Penn photograph for the back jacket of Music for Chameleons. Emaciated fingers delicately support a frail skull: without their help, you feel, the head might simply snap off. One hand, indeed, supplies the vertical hold, the other the horizontal. The skin looks as if it might tear if grazed by a butterfly’s wing. The eyes stare hauntedly out. It cannot be a living author, let alone a man of 55. It reminds one most of those perfectly-preserved bog people dug up in Scandinavia and described by P.V.Glob. In other words – or rather, in words – Mr Capote is announcing his Late Period.

The career began in photographs, too. When Other Voices, Other Rooms was published, ‘the press seized upon an infant prodigy,’ wrote Kenneth Tynan, ‘photographing him crouched behind bushes, lurking in the depths of chairs, or rolling on rugs, always with a lock of fair hair obscuring one wicked eye.’ The cover picture to that first novel was itself notorious: the author, in check waistcoat and bow-tie, lolled knowingly on a chaise longue, angelically diabolical. Shortly afterwards Capote himself spotted two Philadelphia matrons gazing at a pyramid display of his book in a Fifth Avenue shop window. The elder woman adjusted her spectacles, motioned towards the photograph, and commented beadily: ‘Daisy, if that’s a child – he’s dangerous.’ And not just to others, as it transpired.

For the past 35 years, Capote hasn’t merely written: he has presented his career. To begin with, there was the matter of Streckfus Persons becoming Truman Capote. Subsequently, the writer has always been at hand to guide us through his development: the Southern Gothic phase; the New York phase; the confidant-to-criminals phase; and now, the Late Period. These latter two phases have involved not just rousing pre-publicity but also the trumpeting of a new aesthetic. In Cold Blood, an assiduous and at times brilliant work, came packaged as the first ‘non-fiction novel’, as if Dreiser and Stendhal had never existed. And one might add that it wasn’t altogether a new mode even for Capote himself. The writer’s first published work, which appeared in the Mobile Press Register when he was 10, was a prize-winning short story, ‘Old Mr Busybody’. Only one portion of the work ever came out, because ‘somebody suddenly realised that I was serving up a local scandal as fiction, and the second instalment never appeared.’

Since In Cold Blood (1966), Capote has published nothing but reprinted items. For the past few years there has been the constant tease of Answered Prayers – that promised concoction which will be half Proust, half Nigel Dempster – but in the meantime a new aesthetic was getting overdue. The Preface to Music for Chameleons, reprinted from Vogue, provides it. It opens with some routine bravado – ‘Writers, at least those who take genuine risks, who are willing to bite the bullet and walk the plank, have a lot in common with another breed of lonely men – the guys who make a living shooting pool and dealing cards’ – then turns to discuss ‘my fourth, and what I expect will be my final, cycle’. This involves, we are told, radical shifts of stance and voice, evolved during work on Answered Prayers. A new outlook has been provoked by ‘my understanding of the difference between what is true and what is really true’, while an all-encompassing technical problem has finally been faced down: ‘How can a writer successfully combine within a single form ... all he knows about every other form of writing ... film scripts, plays, reportage, poetry, the short story, novellas, the novel. A writer ought to have all his colours, all his abilities available on the same palette for mingling ... But how?’ Assuming the advisability (and the novelty) of this mixed-media quest, what is its key? Rather surprisingly, it lies in the welcoming into the text of the bullet-biting, plank-walking, pool-shooting writer himself: ‘I set myself centre stage, and reconstructed, in a severe, minimal manner, commonplace conversations with everyday people: the superintendent of my building, the masseur at the gym ... After writing several hundreds of pages of this simple-minded sort of thing, I eventually developed a style. I had found a framework into which I could assimilate everything I knew about writing.’ A grand claim: in fact, you can’t get claimier than that.

Music for Chameleons divides into three parts, according to contents and to its fiction-fact mix. It begins with six leisurely, untaxing short stories, with Capote varyingly active as animator or agent. Then comes the most substantial piece, ‘Handcarved Coffins: a non-fiction account of an American crime’. Finally, there are seven ‘Conversational Portraits’, interviews and rambles with friends and celebrities: these are vivid, funny pieces of journalism, especially one in which a quickly fatigued Capote follows his pot-smoking charwoman on her rounds, rootling inquisitively in her clients’ apartments and getting squawked at by a Jewish parrot. This section ends with the affable grilling of Capote’s favourite friend and celebrity – himself (the piece, commissioned for Andy Warhol’s Interview magazine, effortlessly attains the paper’s required tone of frangible self-regard).

The Capote ear remains as responsive as ever to a spectrum of diction, from psychopathic killer to Martinique aristocrat; there are some wry digressions, and some interesting information. But the pieces remain formally irritating. Take the second story, ‘Mr Jones’. Capote once roomed (or says he did) in a brownstone in Brooklyn; next door lodged a blind cripple, Mr Jones, to whom Capote never spoke, and who apparently lived off giving people advice. After a few months, the writer moved out; returning later to collect some belongings, he was told that Mr Jones had disappeared. How? Whither? No one knew. Ten years pass, Capote is on the subway in Moscow when he spots Mr Jones, who isn’t blind, and has sound legs, sitting opposite him. But before he can speak the man gets off.

The story hasn’t lost much in abbreviation, being only two pages long to begin with. Given Capote’s new aesthetic, there are three possibilities. If the story is entirely true, it is quite interesting, surely worth $25 of the Reader’s Digest’s money for their ‘My Strangest Experience’ column. If it is invented, then it still has a quizzing echo, but is far too thin. If it is a mixture – say, if Capote added the Moscow envoi to an otherwise true incident – it still doesn’t go far enough. It’s not, especially, that one wants to be told the why of the events (the answer, presumably, will be a palms-upturned ‘Search me; these things happen’): the problem is simpler – there isn’t enough matter there to fend off the mildest critical So What.

The non-fiction novel veers about in its claims (though it never extends its denial of workaday truth to the point of existential puzzlement, of the nouveau roman); sometimes it merely seems to be asserting that the best journalism can be literature, and that a byline may be fleshed out into a participant. But its proponents do have one thing in common: a desire to have it both ways. They claim to be adding their imaginative insights to their reporter’s facts, to be moulding brute reality with artistry while never losing sight of the truth – the real truth, as Capote prefers it: truth squared. If a reader is tempted to find something boring – when he’s freezing to death on the tundra of The Executioner’s Song, for instance – he’s told that it can’t be boring because it’s true. On the other hand, when he complains that something isn’t true – because, for example, the author couldn’t have been there, couldn’t have heard a particular conversation – he’s told he’s a blockhead and ought to be grateful for the deeper imaginative truth he’s getting given.

In fact, as Music for Chameleons shows, you can’t have your cake and eat it, and the reader may well discover in himself a self-contradictory stance to match the author’s: he may prove capable of both admiring and despising the book at roughly the same time. Having Capote physically present in all his pieces is rather like having an estate agent show you round a house: you’re very grateful to begin with, you’re pleased to be told how the place works, and then after a while you terribly wish you were alone. It’s no coincidence that the best story in the opening section, ‘Mojave’, a box-within-box tale of a couple’s emotional withdrawal from one another (with a powerful, desolate central metaphor), is the only one that fails to feature Capote directly.

Moreover, once the author has put himself centre stage, he simply can’t avoid showing off. The estate agent in him will insist on showing you where all the electric points are, and telling you to mind your head on that obsolete gas-meter which you didn’t need to know about in the first place. An interview-adventure with Pearl Bailey dives off into a cute and pointless paragraph about an earlier professional connection with her and with ‘many gifted men attached to that endeavour: the director was Peter Brook; the choreographer, George Balanchine; Oliver Messel was responsible for the legendarily enchanting decor and costumes.’ Fey, Warholish asides about literature just can’t be shut out (‘I like Agatha Christie, love her. And Raymond Chandler is a great stylist, a poet. Even if his plots are a mess’); nor can assorted chunks of information about the Capote life. It’s undeniably interesting to learn, for example, that he once bedded Errol Flynn: but it’s a hard fact to lodge in an otherwise acute and touching profile of Marilyn Monroe without its being the main thing we remember from the piece. At one point Capote asks himself what he fears most, and replies: ‘Real toads in imaginary gardens.’ It’s hard not to see the writer at times as a toad squatting in among his own fiction.

‘Handcarved Coffins’, Capote’s centrepiece and the direct descendant of In Cold Blood, concerns a series of bizarre murders in a Western state (victims are despatched by amphetamine-crazed rattlesnakes, liquid nicotine, beheading etc), and the writer’s spasmodic involvement in the investigation. For most of its length it is so compellingly narrated that you suspend inquiry into its literary mode; and for once Capote’s own presence, his doubts and excitements, help things along. He adroitly works into the narrative an incident from his childhood when he was frighteningly baptised by a wayside Bible-puncher. This hedge-priest and the supposed killer gradually coalesce in Capote’s mind, leading finally to a climactic meeting (appropriately by a river, with the killer dressed in a rubber suit, as if for mass baptism) in which the writer’s private hauntings and the case’s public resolution join hands. It is a precisely calculated and stunning finale. It is also much too good to be true.

Capote claims it is all true – that only the names have been changed. And perhaps, the tempter whispers, it doesn’t matter whether it’s true or not: isn’t Capote merely offering an aesthetic construct, and shouldn’t we accept it as such? Perhaps, but that’s asking rather a lot. For instance, if we knew that ‘Handcarved Coffins’ was what it feels like – a skilful, pacey piece of fiction – we should give it high praise and say that it reads like a cross between Harry Crews and Ed McBain (with a few silly clichés, like having the hero play chess against the villain, and letting the killer pseudo-confess in the last paragraph). Whereas if we knew it was true, it would be hard to leave the story where Capote leaves it. What about the case? What about justice? Is it the writer’s task merely to muse elegantly on eight murders and then depart? We are back with the questions Tynan put to Capote at the time of In Cold Blood: questions about the exploitation of human material, about decadence – questions which are both irrelevant and central at the same time.

Music for Chameleons is more, and more simply, enjoyable than all of this suggests: it’s light, funny, smoothly-written and smoothly readable. It’s also quite minor, and the claims made for it by its author are risible. Most of all, one regrets the way in which its qualities are visibly distorted by that worst of pressures in American literary life: the demand for the writer as event. Capote, alas, seems no longer capable of merely writing. He performs, he presents himself, he happens. At the close of this book, he declares sympathy for the idea of an after-life. He would like to come back ‘as a bird – preferably a buzzard. A buzzard doesn’t have to bother about his appearance or ability to beguile and please; he doesn’t have to put on airs.’ That should make a nice change.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.