Raphael Samuel

Raphael Samuel is an editor of History Workshop Journal and a fellow of Ruskin College, Oxford.

Making It Up

Raphael Samuel, 4 July 1996

This biography opens with a vivid chapter on Raymond Williams’s funeral. Entitled ‘Prologue, in Memoriam’, it transports the reader to Clodock Church, ‘a plain little building’ in the foothills of the Black Mountains. It is a comfortless day, Fred Inglis tells us. ‘The light fell crooked and the road fell wrong.’ Rooks caw speculatively on the wind, and the weather is appropriately Gothic too, a ‘bitter cold’ February day with ‘vicious showers of sleet and snow’. The mourners make their way along the ‘tatters’ of the old, winding road, passing Harry and Gwen Williams’s cottage, where Raymond grew up. Assembled in the churchyard, ‘Raymond’s young men’ (as his wife, Joy, used to call them) are now middle-aged and showing signs of wear and tear, ‘thinning and unkempt hair … a bad back here, a heavy paunch there’. Sartorially, they are drabbies, ‘awful old grey suits and worse black ties … or else the … uniform of the Left on parade, a dark old coat left open to the weather … corduroy trousers … Tuf boots’. Acting as MC for the occasion, Inglis introduces us to the mourners – Terry Eagleton, ‘small, solid, mischievous’; Charles Swann, ‘wheezing with his awful respiration’; Patrick Parrinder, ‘silent, smiling, ironic’, the best-dressed of the party; Tariq Ali with ‘lustrous brown eyes’ but (Inglis claims) ‘a bit out of it all’.’

North and South

Raphael Samuel, 22 June 1995

‘This is the story of simple working people – their hardships, their humours, but above all their heroism.’ The epigraph which introduced the 1939 screen version of The Stars Look Down – the words are possibly those of A.J. Cronin, the novelist, rather than of Carol Reed, the film’s director – signalled a remarkable turn-around in attitudes to the miners, as well as prefiguring what was to be the leading idiom of British wartime cinema. The success of the film itself (fear of censorship had held it back for three or four years) encouraged a spate of ‘grimly honest’ realist dramas. As Graham Greene remarked of one of them, the colliery winding gear, silhouetted against the sky, the pit disaster and the warning siren became as cinematically familiar as the Eiffel Tower or the Houses of Parliament. A.J. Cronin, the best-selling novelist whose fictions probably did as much as the Beveridge Report – and certainly more than the Thirties poets – to secure Labour’s landslide victory in the 1945 election, had served one of his medical apprenticeships in the Rhondda valley; amputating the leg of a miner trapped in a rock fall had been his initiation in this work and it seems that the disaster in the Scupper Flats, which is the climax of The Stars Look Down, though set in Co. Durham rather than South Wales, was based on a real life rescue operation in which, as the local doctor, he was called on to take part. The Stars Look Down, showing the ways in which human greed put the miner’s life at risk, helped to turn nationalisation from a Fabian dream into something approaching a popular cause.’

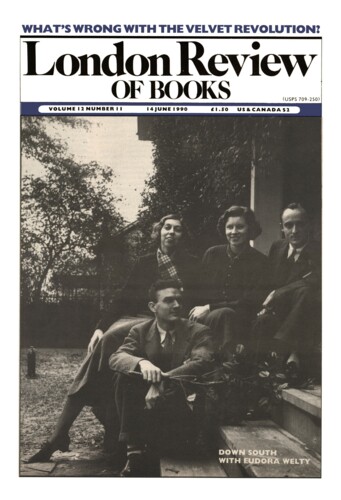

The Return of History

Raphael Samuel, 14 June 1990

The restoration of history to the school ‘core curriculum’, if it takes place, and if it survives the counter-pressures in the Government towards TVEI (Technical and Vocational Educational Initiative), will represent one of the more remarkable pedagogic reversals of our time. The privileged place which the new curriculum gives (in my opinion, quite rightly) to British history is in singular contrast to the implosion which has taken place in English studies, and the abandonment – now endorsed by the National Curriculum Council – of both English literature as a separate classroom subject, and set texts, the ‘cultural heritage’ which it was the special mission of school English to transmit.’

Pieces about Raphael Samuel in the LRB

Ladders last a long time: Reading Raphael Samuel

Florence Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, 23 May 2024

Raphael Samuel set out his stall as a practitioner of ‘people’s history’. This was a capacious category: it could be liberal, radical, nationalist or socialist; macro or microhistorical.

Cadres: Communism in Britain

Eric Hobsbawm, 26 April 2007

Lenin’s ‘vanguard party’ of Marxist cadres, disciplined and ideally full-time, his ‘professional revolutionaries’, was the most formidable political invention of the...

Lever-Arch Inquisitor

John Barrell, 29 October 1998

When Raphael Samuel died, the second volume of his projected trilogy Theatres of Memory was left unfinished. Some of the longer essays it was intended to contain were unwritten or unannotated or...

Retrochic

Keith Thomas, 20 April 1995

Raphael Samuel and I were undergraduates together at Balliol in the early Fifties. Bibliographically omnivorous, buried under piles of notes and unfinished essays, inkstained and dishevelled, he...

Down and Out in London

David Cannadine, 16 July 1981

One of the most spectacular examples of embourgeoisement in the 1970s was the transformation of the history workshops held at Ruskin College, Oxford from ephemeral, marginal, near-clandestine...

In Search of People’s History

Eric Hobsbawm, 19 March 1981

Histories claiming to take ‘peoples’ (as distinct from top people) as their subject began to be written under appropriate titles in the early 19th century, era of revolutions and national revivals....

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.