Peter Lamarque

Peter Lamarque is a lecturer in philosophy at the University of Stirling.

Literary Theory

17 October 1985

Durability

Peter Lamarque, 15 September 1983

The idea of development, either in the work of individual artists or in terms of ‘schools’, ‘movements’ or styles, is a dominant feature of our conception of European art. There is no theoretical problem more pressing in art history than that of explaining such development. How do we get from Cimabue’s Madonna Enthroned to Raphael’s Alba Madonna, or even from Brunelleschi to Bramante? And why do such changes occur?

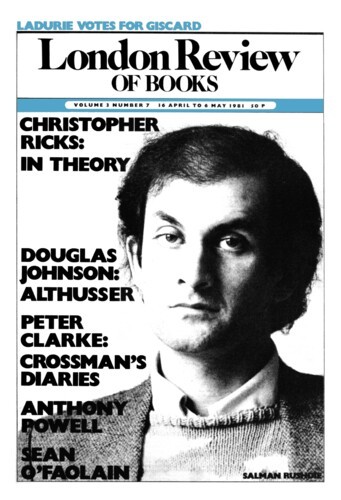

In theory

16 April 1981

Works of Art

Peter Lamarque, 2 April 1981

Generalising across the arts is a tricky business. Can we really expect to find anything in common between, say, Ulysses, Der Rosenkavalier, the ‘Donna Velata’ and Donatello’s St George in virtue of which they are all works of art? As if that were not hard enough, try adding prints, films, dances and buildings and the problem becomes intractable. Yet traditionally the aim of aesthetics has been to undertake an abstraction from the properties of particular works of art, and of different forms of art, with precisely the hope of isolating just those general features which are supposed to characterise or define the nature of art itself. To discover defining, or even characteristic, properties of art, if such there be, presupposes an answer to even more basic, ontological, questions concerning what sorts of things or entities works of art are. Are they physical objects, ideas, universals, classes, or what?

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.