Paul Seabright

Paul Seabright is a professor of economics at the University of Toulouse-1.

Down with deflation!

Paul Seabright, 12 December 1996

The power of central bankers – about which Edward Luttwak wrote in the LRB of 14 November – arises not just from their control over important aspects of economic policy, but also from the acceptance by the rest of us of what they may legitimately do in the exercise of this control. Until recently, our acceptance of the notion that central bankers should be committed to price stability has been entirely uncritical; and price stability (not low, but zero inflation) is what the European Central Bank will be required to maintain. But now that European Monetary Union suddenly looks a real, even an imminent possibility, a skirmish has broken out among economists about whether price stability is what monetary policy should be required to achieve.

Alas! Deceived

25 March 1993

Five Tools for Going Forward

Paul Seabright, 23 July 1992

Twenty years after The Limits to Growth comes the sequel. It’s a hard act to follow: the original sold nine million copies and made its authors and backers, the so-called Club of Rome, famous with its prophecy that the comfortable optimism of the Sixties was threatened by a combination of population growth, resource exhaustion and the effluents produced by affluence. The authors used a large computer model to project economic and demographic trends, and predicted a collapse of living standards by the middle of the 21st century unless dramatic changes were made. A decade after the Cuba missile crisis, a world that was learning to live with the superpower confrontation reacted in alarm to the warning that a population explosion would be no less deadly than that of the ICBMs, and much harder to control. Some pessimists even derived a certain lugubrious pleasure from thinking the baby boom more inevitable and more damaging than the atomic kind. Demographic warfare differs from the traditional sort in that going nuclear usually signals de-escalation. But the authors warned that slowing the birth rate (did they choose the title Club of Rome deliberately?) would be nothing like enough to avoid calamity. At any foreseeable stable population level, even existing consumption trends would exhaust the world’s resources and pollute its environment beyond repair.

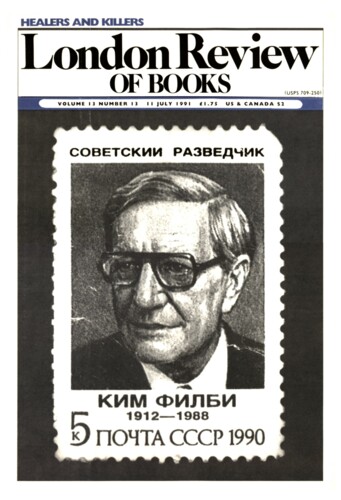

Death by erosion

Paul Seabright, 11 July 1991

Two of Britain’s largest remaining nationalised industries – the Church of England and the National Health Service – have recently acquired new bosses who have publicly declared that the Nineties will be a decade of major change. This has set me wondering what kind of reaction George Carey might expect if the plans he had in mind for his own organisation were at all like those being implemented under William Waldegrave. Capitation fees and evangelism budgets for individual priests? The chance for churches to opt out of diocesan control? A division between purchasers and providers so that a diocese can draft in the Jehovah’s Witnesses or the Wee Frees if it suspects that the fare in its own parishes is becoming a little dull? A small minority would no doubt welcome these along with other transatlantic innovations, but for most the sheer, well, commercialism of it all would provoke a delicious shudder of horror.’

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.