Paul Edwards

Paul Edwards editor of Enemy News, the journal of the Wyndham Lewis Society, works in an Industrial Language Training Unit in East London, where he designs courses on work-place communications. His edition of Lewis’s Rotting Hill was published on 18 February (Black Sparrow, distributed by Air-life Books, 349 pp., £19.95 and £11.95, 0 87685 647 4).

Dialectical Satire

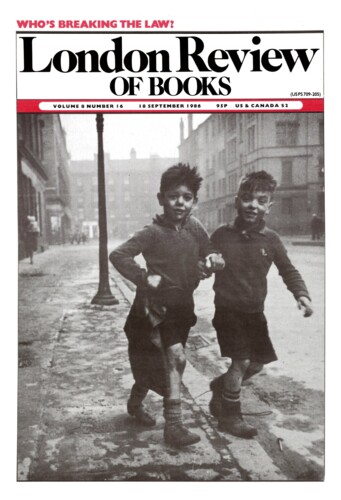

Paul Edwards, 18 September 1986

‘If I had been Lenin I would have introduced the concept “shit” instead of “matter”. Shit is primary. How does that sound?! But it’s not only primary. It’s secondary, as well. And that puts paid to all philosophical argument.’ So much for dialectical materialism, a philosophy for which Alexander Zinoviev feels a professional scorn. Zinoviev’s academic speciality is logic, and his main work in that field (popularised in a forbidding volume called Logical Physics) is an analysis of the cogency and implications of the language of science. The results of this analysis are frequently counter-intuitive, apparently, but tell us nothing about the world: ‘the sphere of application of logic is language and only language.’ This is a rarified subject, but we are all familiar enough with the habits of thought subsumed under ‘dialectical logic’ not to be surprised that Zinoviev should also be the source of a gross and unstanchable flow of satire. The Madhouse, which dates from 1980, is the latest of his novels to be published here in translation. Since then, Zinoviev has turned to the subject of émigré life, but The Madhouse concerns the thoughts and fate of an intellectual misfit in Russia.

The Education of Gideon Chase

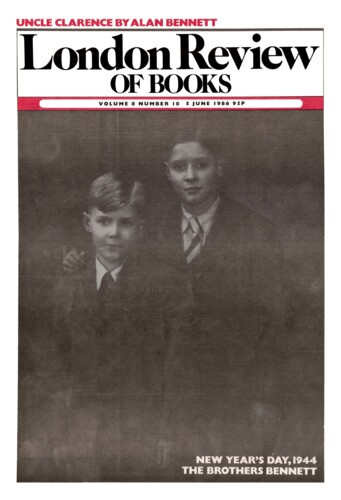

Paul Edwards, 5 June 1986

‘Mastah Eastman just now come chop-chop say you plomise give him sketch-y lesson, you no lemember bime-by?’ It is shocking to find such dialogue – so squarely within the racist convention of the comic ‘Chinaman’ – seven pages into Timothy Mo’s novel about the first Opium War. Is this shameful convention, with its ‘all rightees’ and ‘yes Missees’, being endorsed as mimetically accurate by a writer at home in both English and Chinese cultures? If he does endorse it, he does so only to the extent of using it to show how small the point of contact between two cultures can be. Mo’s hero compares language to a delta; and just as the Western traders in the 1830s had access to China only through one part of the treacherous Pearl River delta and through the precarious stockade of ‘Factories’ at Canton, so linguistic contact also was straitened and treacherous. The pidgin that defined for popular consumption an image of the Chinese (along with opium dens and tong gangs) has its origin, Mo shows us, in purely commercial exchanges, where it functions as an adequate bridge between cultures so long as it carries only commercial traffic: ‘ “Half-um?” he says witheringly. “Half-um? Me tink-ee mak-ee half-um silver dollar can buy all-um duck market hab got Canton-side.” ’ (This time it is the American Eastman talking.) For any other form of cultural exchange it is worse than useless – ‘ridiculous nonsense’, as Mo reassuringly calls it later in the novel. The word ‘pidgin’, he might have added, is simply a Chinese corruption of the word ‘business’. Pidgin English is business English, purely instrumental in origin.’

Intimations of Immortality

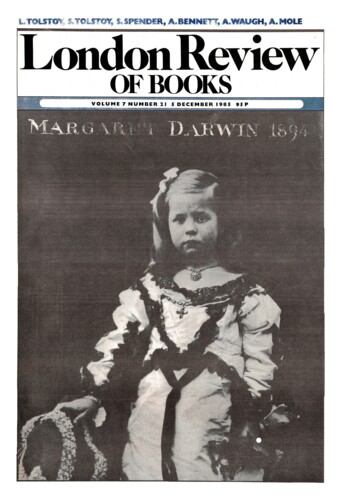

5 December 1985

Pieces about Paul Edwards in the LRB

My God, they stink! Wyndham Lewis goes for it

Seamus Perry, 5 December 2024

Style in Lewis’s prose is a sort of triumph of the will over the external world of people and things, ‘that fat mass you browse on’, as Lewis rather horribly put it. ‘The act of creation ... is...

Apoplectic Gristle: Wyndham Lewis

David Trotter, 25 January 2001

The day he first met Wyndham Lewis, shortly after the end of the First World War, Ernest Hemingway was teaching Ezra Pound how to box. The encounter took place in Paris, where Pound had a studio,...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.