Michael Dummett

Michael Dummett The Game of Tarot and Twelve Tarot Games were reviewed in the last issue of this paper. He is Wykeham Professor of Logic at the University of Oxford. His book, Frege: Philosophy of Language, was published in 1973.

Linguistics demythologised

Michael Dummett, 19 August 1982

This book, a follow-up to the same author’s The Language Makers, published in 1980, is a wholesale onslaught on ‘orthodox modern linguistics’. It is, and is meant to be, provocative and stimulating, and will prompt fruitful debate in an area still made murky by difficult conceptual problems, but surely rightly seen as critical in our present state of knowledge of ourselves and of the world.

Power and Prejudice

Michael Dummett, 7 October 1982

This short book was originally presented as a report to the international consultation held in the Netherlands by the World Council of Churches Programme to Combat Racism in June 1980. It is a portrait of the society we live in, as it presents itself to its black citizens; and it is a horrifying portrait. Though its author, who teaches at Thames Polytechnic, has hopefully entitled it Now you do know, he expresses in his Preface pessimism about whether many white people in Britain will read it, or will believe it if they do. I do not intend in this review to summarise its contents: it is already very compressed, and quickly read. Instead, I will try to remove the principal obstacle to people’s reading it or taking it seriously. This obstacle is the thought: ‘This is a portrait of a rampantly racist society; though I know there is a certain amount of racism around, I simply cannot recognise such a portrait as depicting the country I live in.’ This thought is very natural: it is one for which those, like Downing, who know how things are here for black people and try to communicate that knowledge, usually make no allowance. It is enormously important to grasp why the thought is mistaken. Someone may be aware that he knows very little about the workings of, say, the magistrates’ courts or the welfare services, particularly as they affect black people. But he knows, or he thinks he knows, what the level of racial prejudice is amongst the people with whom he comes into contact. He acknowledges that such prejudice exists, even that it is deplorably prevalent; but, he thinks, it is not virulent enough or widespread enough to render credible the picture Downing presents of a society utterly racist in character. His common experience simply does not match this picture: no specialised knowledge is required to judge that it must be false.

Eurochess

Michael Dummett, 24 January 1985

The history of a game, like that of an art form such as ballet, has an external and an internal aspect, which in neither case can be kept sharply separated. Under the external aspect, we must, for each period, ask such questions as these. In what countries was it played? Among which social groups? Did they play at home, or in cafés, clubs or gaming houses? Was it played only at the local level, or were there organised regional, national or international competitions? Was there an authority to lay down the rules? Was the game played for high stakes, for moderate ones or for none? Did the players regard it as a serious pursuit or a light recreation? Did they play rapidly or with deliberation, talking as they played or in intent silence? Was it generally regarded with respect, despised as a frivolous waste of time, condemned as degrading or treated with indifference?

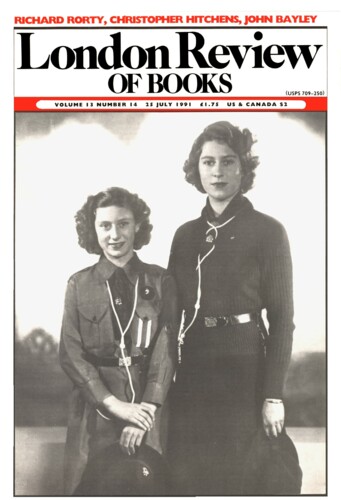

Trick-taking

Michael Dummett, 25 July 1991

Excitement was aroused by the announcement, last September, of a double discovery: the actual rules, on a cuneiform tablet, of a board game thought to date from 3300 BC, of which only some surviving boards had previously been known, and a living individual from a Jewish community in Cochin who had herself played that very game before she migrated to Israel, and could recall the rules in accordance with which she had then played it. Academics gathered at the British Museum to confer about board games of the ancient world.

Pieces about Michael Dummett in the LRB

Frege and his Rivals

Adam Morton, 19 August 1982

Philosophy is a bitchy subject. That is not to say that philosophers are nastier to each other in print than people in other subjects are, but that in philosophy the distinction between academic...

Tarot Triumph

Edmund Leach, 4 September 1980

During recent decades a variety of very distinguished academics have taken time off from their learned pursuits to write imitation Agatha Christie detective stories, so when I first learned that...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.