M.F. Burnyeat

M.F. Burnyeat has returned to Robinson College, Cambridge after ten years as senior research fellow in philosophy at All Souls. He is the author of The Theaetetus of Plato, among other books.

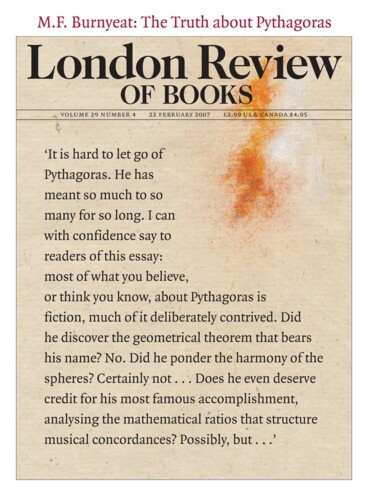

Other Lives: The Truth about Pythagoras

M.F. Burnyeat, 22 February 2007

It is hard to let go of Pythagoras. He has meant so much to so many for so long. I can with confidence say to readers of this essay: most of what you believe, or think you know, about Pythagoras is fiction, much of it deliberately contrived. Did he discover the geometrical theorem that bears his name? No. Did he ponder the harmony of the spheres? Certainly not: celestial spheres were first excogitated decades or more after Pythagoras’ death. Does he even deserve credit for his most famous accomplishment, analysing the mathematical ratios that structure musical concordances? Possibly, but there is little reason to believe the stories about his being the first to discover them, and compelling reason not to believe the oft-told story about how he did it. Allegedly, as he was passing a smithy, he heard that the sounds made by the hammers exemplified the intervals of fourth, fifth and octave, so he measured their weights and found their ratios to be respectively 4:3, 3:2, 2:1. Unfortunately for this anecdote, recently rehashed in the article on Pythagoras in Grove Music Online, the sounds made by a blow do not vary proportionately with the weight of the instrument used.

Diary: The Siberian concept of theft

M.F. Burnyeat, 19 February 2004

On the night sleeper from Khabarovsk to Vladivostok I foolishly left my money belt in the loo. An hour and a half later, I realised I no longer had it with me. Panic. I was without passport, credit cards, return plane tickets, $500 and £50, not to mention a quantity of Russian rubles and South Korean won (I had reached Khabarovsk by way of a stop-off in Seoul). The attendant in my coach...

By the Dog: How Plato Works

M.F. Burnyeat, 7 August 2003

Thrasymachus, a well-known teacher of rhetoric, has listened with growing impatience to the discussion of justice in the first Book of Plato’s Republic. ‘What balderdash you two have been talking,’ he says to Socrates and Polemarchus. He cannot wait to astound the company, and win their acclaim, by unmasking justice as nothing but the advantage of the stronger, dominant...

Excuses for Madness: On Anger

M.F. Burnyeat, 17 October 2002

The solution, therefore, is to moderate anger so as to avoid the excesses of Achilles, and to train people to be angry on the right occasions only, in the appropriate manner and degree. Which might mean very angry indeed, especially on the battlefield.

Pieces about M.F. Burnyeat in the LRB

The Sponge of Apelles

Alexander Nehamas, 3 October 1985

Thales of Miletus, with whom histories of Western philosophy conventionally begin, was said to have been so concerned with the heavens that he fell into a well while he was gazing at the stars....

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.