Karl Miller

Karl Miller was the first editor of the LRB.

Literary Supplements

Karl Miller, 21 March 1991

Denis Donoghue has written a seductive book. Perhaps it could be said that he has spliced together two books, one of which is more seductive than the other. One of them narrates. The othes contemplates. Warren-point is a series of passages, not unlike journal entries, some of which deal with his youth in the Northern Irish seaside town of that name, and in particular with his awareness, and acceptance, of his father, while the others consist of the annotations of the professor and man of letters. I don’t mean to do as the Leavises did with Daniel Deronda and propose a Solomonic severance: let’s just say that many readers would he very sorry to lose the memories if it were to come to a cut.

Elephant Head

Karl Miller, 27 September 1990

Naipaul’s grandfather, a Hindu of the Brahmin caste, left India to work as an indentured labourer in the West Indies. In 1962, Naipaul went to India for a year’s stay which became a book, entitled An Area of Darkness. The title refers to what the country had been for him in his West Indian Hindu enclave. In 1977, India: A Wounded Civilisation appeared, in the aftermath of Mrs Gandhi’s Emergency: sombre thoughts were expressed about the country’s instability, its ‘intellectual vacuum’, its ‘fantasies of spirituality’. The ideas of Mahatma Gandhi were felt to offer no escape from ‘the present uncertainty and emptiness’. Both books have rankled with citizens of his ancestral country, and I have heard that he has lately been reported there as regretting some part of what he wrote about it in earlier times. An Area of Darkness is a literary travel book which seems now to taste of the British Fifties, to incorporate a Movement comedy of manners. It is markedly forthcoming both of himself and his opinions: he is no more loth than Salman Rushdie has sometimes been to give offence. He speaks of a ‘static, decayed society’. He says that he’d gone to India with a vague sense of caste and a Hindu ‘horror of the unclean’, and he emerges from the book a seasoned coprophobe: ‘Indians defecate everywhere. They defecate, mostly, beside the railway tracks. But they also defecate on the beaches; they defecate on the hills; they defecate on the river banks; they defecate on the streets; they never look for cover.’ This Churchillian passage may be among his current regrets.

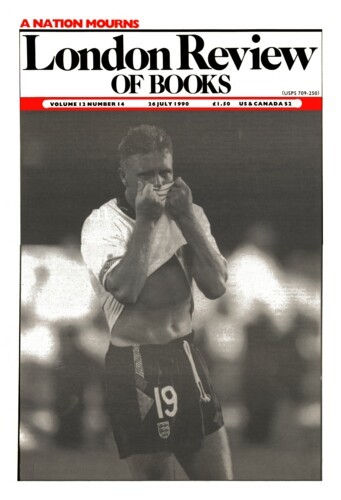

Diary: On the 1990 World Cup

Karl Miller, 26 July 1990

An article in the Independent of 10 July was headed with these remarkable words: ‘Patrick Barclay reflects on a World Cup which was largely lacking in drama, individual dynamism and moments to cherish in the memory.’ This is not a description of the World Cup that I have been watching. But it is a good description of the coverage of the football which was offered by Patrick Barclay, by other British journalists, and by experts and commentators who were heard from on television. The 1990 World Cup produced, as it was bound to, its disappointments, patches of dullness and travesties of justice. It was doubtfully regulated and often poorly refereed. But its best stuff was enthralling, and as an occasion in the history of the human race its interest was first-rate. No one team was a match for the Brazilians of 1970 and before, but the Italians were among the most skilful and beautiful sides ever to grace the world game: the true winners of the cup, in my opinion, let down at the last by a lack of aggression and brute force, and of the luck that was so lavishly bestowed elsewhere.

Great Portland Street Blues

Karl Miller, 25 January 1990

Boswell’s life of Boswell has reached its conclusion, this being the 13th in the series of journals brought out by the team responsible for the Yale Editions of his Private Papers. It opens two hundred years ago in London, during the winter of 1789. Frosty weather – the widower is warm against ‘the French insurrection’. Christmas Day takes him to church. Three years go by, and on the same day the same church receives him. ‘It vexed me that even on the festival of Christmas I was melancholy. I went with my son James to St George’s, Hanover Square, and had some elevation of heart in that hallowed dome. Saw Miss Upton at a distance’ – then back to the family turkey in Great Portland Street. The content of this last journal – previewed in the account of Boswell’s later life which was published six years ago by one of the present editors, Frank Brady – is the worse for its author’s frustrations, prostrations and despairs, interesting though he can sometimes make them appear; it conveys what can often seem like a bitter end for the likely lad from Ayrshire; Boswell’s last legs are apt to give way. Nevertheless, he gets up and keeps going, and keeps writing it down. Such states are his old friends, after all. The journal is no discouragement to supposing that Boswell’s life of Boswell is among the crown jewels of confessional literature.’

Pieces about Karl Miller in the LRB

About Myself: James Hogg

Liam McIlvanney, 18 November 2004

On a winter’s evening in 1803, James Hogg turned up for dinner at the home of Walter Scott. The man his host liked to call ‘the honest grunter’ was shown into the drawing-room,...

Roaming the stations of the world: Seamus Heaney

Patrick McGuinness, 3 January 2002

In a shrewd and sympathetic essay on Dylan Thomas published in The Redress of Poetry, Seamus Heaney found a memorable set of metaphors for Thomas’s poetic procedures: he ‘plunged into...

Disastered Me

Ian Hamilton, 9 September 1993

On the train, sunk on dusty and sagging cushions in our corner seats, Lotte and I spoke of our attachment to one another. I was as weak as I could be when I got off the train. We made our way to...

Being two is half the fun

John Bayley, 4 July 1985

‘The principal thing was to get away.’ So Conrad wrote in A Personal Memoir, and there is a characteristic division between the sobriety of the utterance, its air of principled and...

Adulterers’ Distress

Philip Horne, 21 July 1983

The order in which we read the short stories in a collection makes a difference. Our hopping and skipping out of sequence can often disturb the lines or blunt the point of a special arrangement,...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.