Short Cuts: Starved for Words

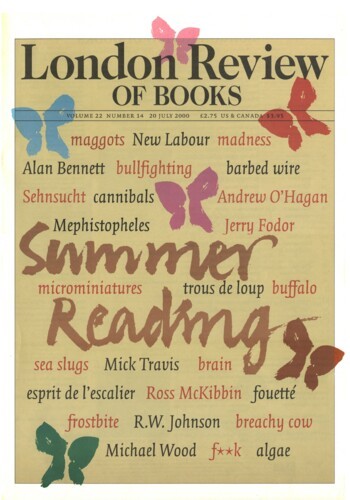

John Sturrock, 20 July 2000

When statistics start horning in on our language, or the way we use it, the results are seldom quite what we’d be happy to hear. To be told that, day in, day out, we rely on some wretchedly skimpy proportion, a bare few thousand, of the uncommonly luxuriant word-hoard available to us anglophones, is chastening, leading us at best into sporadic efforts to stretch our working vocabularies by bringing into play delightful words we’ve always known but have somehow never got around to airing in public. This is one way of warding off that nasty feeling that we could perfectly well get by in life with a starveling lexicon, that no one would even notice the repetitions, in an age that long ago rewrung the neck of eloquence.