John M. Ellis

John M. Ellis is an emeritus professor of German literature at the University of California, Santa Cruz. His books include Against Deconstruction and The Breakdown of Higher Education.

Thinking Persons

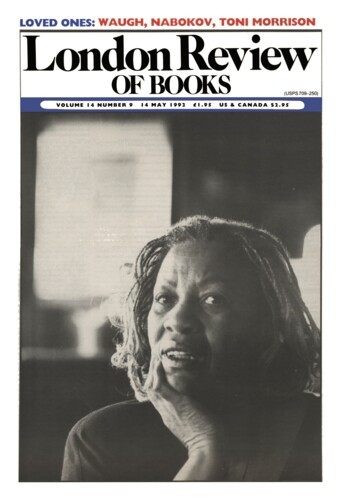

John Ellis, 14 May 1992

These five books continue in then very different ways the intense debate about the purpose of literary criticism and its relation to ‘theory’. Addressing Frank Kermode has its origin in a conference devoted to Kermode’s work. Five papers selected from those delivered at the conference are followed by a reply from Kermode himself; five more follow which ‘acknowledge, more or less directly’, his ‘influence’. The uncertainty visible here betrays some wishful thinking on the part of the editors, for many of these essays are conventional festschrift contributions largely unrelated to the thought of the figure whom they honour. Three of the contributors do, however, engage Kermode’s thought in a fairly serious way: John Stokes, George Hunter and Patrick Parrinder. Two ways of doing so were possible. Either Kermode’s general view of the critic’s task or his ideas concerning specific texts or groups of texts could have been the focus of attention. Stokes and Hunter choose the second of these possibilities and examine aspects of Kermode’s Romantic Image and Forms of Attention respectively; Parrinder objects to Kermode’s general view of criticism. Kermode’s response – appropriately enough, the most interesting essay in the book – is both explicitly and implicitly more concerned with Parrinder’s comments than with any other issue raised by his critics. Taken together with the prologue to his An Appetite for Poetry (which appeared in the same year as the conference), it gives us a clear and sometimes forceful account of how Kermode views the contemporary scene.’

Radical Literary Theory

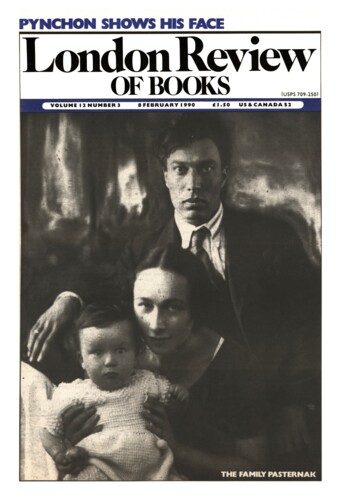

John Ellis, 8 February 1990

When theory of literature first began to make claims upon the attention of literary scholars and critics several decades ago, the meaning of the word ‘theory’ was clear enough from its use in other fields: it referred to a consciously analytical scrutiny of the concepts and practices of literary criticism, which is what anyone unfamiliar with criticism but familiar with the meaning of the word ‘theory’ in other contexts would have assumed. To be sure, the theorists of that era were in practice often allied with the New Criticism, and so they were generally critical of the prevailing historical and biographical orthodoxy. But the fact that theoretical analysis tended towards revision of the status quo was natural enough, and it was again consistent with what theory did anywhere. More recently, however, the term ‘literary theory’ has begun to seem not to refer broadly to the activity of analysis, but more narrowly to a distinct viewpoint, even an ideology. This is a strange development, since now we have a particular set of assumptions and assertions – in fact, an orthodoxy – as the reference of a word which used to be about the business of analysing such things.’

Doing something different

John Ellis, 27 July 1989

Before Stanley Fish started doing what comes naturally, he wrote standard works of literary criticism which dealt, as most such books do, with particular literary figures and periods. Then, in 1980, he published his first volume devoted to theory of criticism, Is there a text in this class?, a collection of his essays from the Seventies. Doing what comes naturally is Fish’s second volume of theory, but while this, too, is a collection of his essays from the previous decade, it is quite different in important respects. Is there a text was devoted to a single issue in theory – reader-oriented criticism – and the sequence of the essays chronicled Fish’s progress as he grappled with the problems raised by a subjectivist view of interpretation; there was something almost autobiographical about the way in which the editorial introductions to successive essays commented on each as a stage in Fish’s thought. The relative paucity of references to other work on this topic reinforced the general impression of an individual’s lonely theoretical journey.’

Pieces about John M. Ellis in the LRB

Talk about doing

Frank Kermode, 26 October 1989

Anyone presuming to review works of modern literary theory must expect to be depressed by an encounter with large quantities of deformed prose. The great ones began it, and aspiring theorists...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.