James Campbell

James Campbell’s biography of James Baldwin, Talking at the Gates, has recently been reissued in the US.

Never Dreary

20 May 2021

White Lies: Nella Larsen

James Campbell, 5 October 2006

Writing in the New Yorker in April 1986, Calvin Trillin told the story of Susie Guillory, a native of Louisiana who, when applying for a passport, discovered that she was African American. According to the state’s ‘one-drop rule’, Americans with even a 1 in 32 part of Negro blood – or a nameless, faceless great-great-great-grandfather – were classified as...

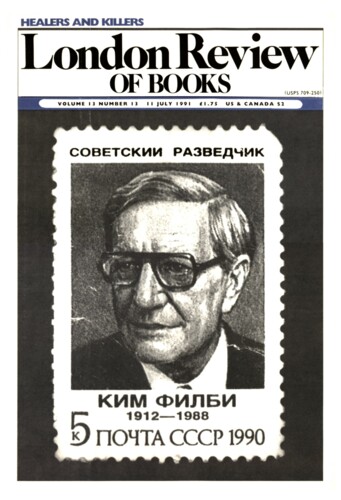

Answering back

James Campbell, 11 July 1991

‘European literature,’ wrote David Dabydeen in his essay ‘On not being Milton: Nigger Talk in England Today’, ‘is littered with blacks like Man Friday, who falls to earth to worship Crusoe’s magical gun, or the savage in Conrad’s steamship.’ He could have added that American literature is too, from Uncle Tom to Nigger Jim to Porgy and Bess and Dilsey in The Sound and the Fury. The Americans, under the guidance first of the great W.E.B DuBois, then of the poets Langston Hughes and Sterling Brown, and next a line of novelists headed by Richard Wright, began the task of reclamation about two generations earlier than the Caribbean writers who identified – if one can nowadays put it that way – with Europe, specifically England. Their literary industry, centred largely in London, only really switched on the power in the 1950s. Novelists such as George Lamming, Samuel Selvon, John Hearne, Andrew Salkey and V.S. Naipaul were among the first voices from the outposts of Empire to talk back. Not for them ‘clapping his hands and stamping his feet’ in order to communicate, like Conrad’s fireman (‘and he had filed teeth, too’). This black man was articulate and eloquent, with a sophisticated sense of his place in the old order. He told his own tale and in the process informed readers – including readers of Conrad, Waugh, Greene and others – that giving another side of the story meant finding another way to tell it.’

Sweet Fifteen

James Campbell, 3 November 1983

‘I couldn’t get in touch with my feelings,’ Marlene Olive remarked one day after it was all over. ‘Lots of times I thought my dad was still alive.’ This must be deemed a serious failure of perception on her part, since with Chuck Riley, her teenage boyfriend and co-star in the true story of Bad Blood, Marlene murdered her parents in an act of astounding brutality. ‘Spaced’ on LSD, Chuck embedded a hammer in Mrs Olive’s skull with such force that it required his full strength with both hands to remove it. Pumping four bullets into Mr Olive a minute later was charitable by comparison. Although she spent the next hour soothing, reassuring and sexually flattering Chuck, Marlene could not evade her unease. For months she had talked about killing her parents, plotted it, and finally bullied Chuck into striking the blows, only to find herself strangely unconvinced. As far as her mother was concerned, it was good riddance, but almost immediately she felt the death of her father as a genuine loss and wished him back. It is with morbid amusement that the reader finds her writing to Chuck complaining of loneliness a month after they were separated by confinement: ‘I have no family and no real friends.’

Pieces about James Campbell in the LRB

Knights of the Road: the Beat generation

Tom Clark, 6 July 2000

When Allen Ginsberg’s Beat vision-quest came through England in the spring of 1965, I was appointed by this famous renegade minstrel to set down his legend for the Paris Review....

Tears in the Café Select

Christopher Prendergast, 9 March 1995

Paris figures in the titles of both James Campbell’s and Peter Lennon’s books, but this is a restricted, specialised Paris. Campbell takes us into something called the...

White Man’s Heaven

Michael Wood, 7 February 1991

It may be an accident of rereading that makes me want to put James Baldwin’s essays and novels together, to see The Fire Next Time and Giovanni’s Room, for example, as versions of...

England’s End

Peter Campbell, 7 June 1984

They should be called the Kondratieff Laureates. Fifty years ago, when the economic cycle last hit bottom, J.B. Priestley made his English Journey. A few years later Orwell wrote The Road to...

Read anywhere with the London Review of Books app, available now from the App Store for Apple devices, Google Play for Android devices and Amazon for your Kindle Fire.

Sign up to our newsletter

For highlights from the latest issue, our archive and the blog, as well as news, events and exclusive promotions.